8.1 Food Security

Section Goals:

- Describe a comprehensive definition of food insecurity.

- Connect the “Western Diet” with health outcomes.

- Introduce basic nutrition facts.

Hunger Continues to Present a Challenge

Progress continues in the fight against hunger, yet an unacceptably large number of people lack the food they need for an active and healthy life. The latest available estimates indicate that about 795 million people in the world – just over one in nine –still go to bed hungry every night, and an even greater number live in poverty (defined as living on less than $1.25 per day). Poverty—not food availability—is the major driver of food insecurity. Improvements in agricultural productivity are necessary to increase rural household incomes and access to available food but are insufficient to ensure food security. Evidence indicates that poverty reduction and food security do not necessarily move in tandem. The main problem is lack of economic (social and physical) access to food at national and household levels and inadequate nutrition (or hidden hunger). Food security not only requires an adequate supply of food but also entails availability, access, and utilization by all—people of all ages, genders, ethnicities, religions, and socioeconomic levels.

From Agriculture to Food Security

Agriculture and food security are inextricably linked. The agricultural sector in each country is dependent on the available natural resources, as well as the politics that govern those resources. Staple food crops are the main source of dietary energy in the human diet and include things such as rice, wheat, sweet potatoes, maize, and cassava.

Food security

Food security is essentially built on four pillars: availability, access, utilization and stability. An individual must have access to sufficient food of the right dietary mix (quality) at all times to be food secure. Those who never have sufficient quality food are chronically food insecure.

When food security is analyzed at the national level, an understanding not only of national production is important, but also of the country’s access to food from the global market, its foreign exchange earnings, and its citizens’ consumer choices. Food security analyzed at the household level is conditioned by a household’s own food production and household members’ ability to purchase food of the right quality and diversity in the market place. However, it is only at the individual level that the analysis can be truly accurate because only through understanding who consumes what can we appreciate the impact of sociocultural and gender inequalities on people’s ability to meet their nutritional needs.

The definition of food security is often applied at varying levels of aggregation, despite its articulation at the individual level. The importance of a pillar depends on the level of aggregation being addressed. At a global level, the important pillar is food availability. Does global agricultural activity produce sufficient food to feed all the world’s inhabitants? The answer today is yes, but it may not be true in the future given the impact of a growing world population, emerging plant and animal pests and diseases, declining soil productivity and environmental quality, increasing use of land for fuel rather than food, and lack of attention to agricultural research and development, among other factors.

The third pillar, food utilization, essentially translates the food available to a household into nutritional security for its members. One aspect of utilization is analyzed in terms of distribution according to need. Nutritional standards exist for the actual nutritional needs of men, women, boys, and girls of different ages and life phases (that is, pregnant women), but these “needs” are often socially constructed based on culture. For example, in South Asia evidence shows that women eat after everyone else has eaten and are less likely than men in the same household to consume preferred foods such as meats and fish. Hidden hunger commonly results from poor food utilization: that is, a person’s diet lacks the appropriate balance of macro- (calories) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). Individuals may look well nourished and consume sufficient calories but be deficient in key micronutrients such as vitamin A, iron, and iodine.

Food stability is when a population, household, or individual has access to food at all times and does not risk losing access as a consequence of cyclical events, such as the dry season. When some lacks food stability, they have malnutrition, a lack of essential nutrients. This is economically costly because it can cost individuals 10 percent of their lifetime earnings and nations 2 to 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the worst-affected countries (Alderman 2005). Achieving food security is even more challenging in the context of HIV and AIDS. HIV affects people’s physical ability to produce and use food, reallocating household labor, increasing the work burden on women, and preventing widows and children from inheriting land and productive resources.

Challenges Beyond Basic Survival

The challenge of global food security is very complex. Because food is an inherent and interlinked part of human health, the global food systems impacts the lives of individuals in complex and unobvious ways.

Though many practitioners advocate that health is much more complex than just weight, the fact remains that a weight-based framework exists in the research and literature about global health. Because of the correlation of obesity with other health impacts, it will be discusses here. But, as with other parts of this textbook, please do not take this as a judgement or a blame on the individual; take the dominant narrative within the context of who or what that narrative benefits. The global food system has succeeded in producing enough quantity to overcome significant hunger challenges that have plagued our society in history, but it has come with a cost to individual health. And who benefits from individuals feeling that they are solely responsible for their own heath, even when factors beyond their control regulate the global food system?

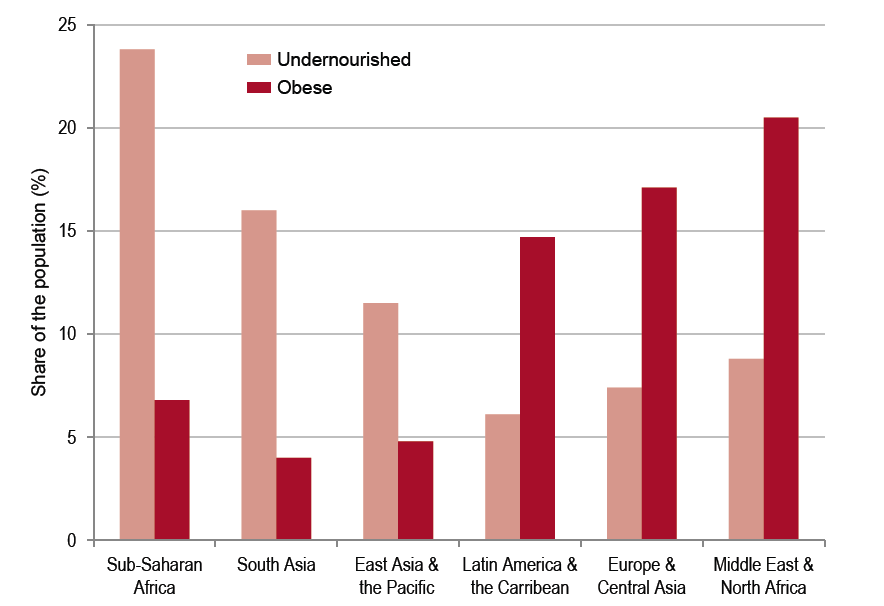

What is called an overweight/obesity problem initially emerged in industrial countries. For various reasons, this measure of human health now increasingly occurs in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in urban settings. In these areas, there is a triple burden of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, and overweight/obesity. There is significant variation by region; some have very high rates of undernourishment and low rates of obesity, while in other regions the opposite is true (Figure 1).

Obesity is correlated with a number of noncommunicable diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. However, it also is correlated with better survival of individuals in extreme disasters and in populations of older adults. Additionally, though it is well understood that chronic stress can cause similar chronic health effects, and well proven that there is significant “fat stigma” in the world, especially in the United States, the data, doctors, researchers and policy makers have not been able to reduce their focus on weight and shift to reviewing markers of health instead. To focus on heath indicators here, we can say that there is rise in diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers which correlates with what is called a Western Diet: an increasing availability of processed, affordable, and effectively marketed food. The global food system is falling short by causing poor health outcomes even as the quantity and availability and reliability saves a large number from starvation.

Nutrients, Energy, and Building Materials

A very brief introduction to nutrition is included here. The goal of its inclusion is to highlight that there are complexities in maintaining a functioning, healthy, human body. Ensuring that the global population has food security, as we just learned, means that the nutrition balance of individuals matters, not just the quantity of food. This understanding must be a part of any effort to change the global food system.

Nutrients are chemical elements or compounds that the body needs for normal functioning and good health. There are six main classes of nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, water, vitamins, and minerals. The body needs these nutrients for three basic purposes: energy, building materials, and control of body processes.

A steady supply of energy is needed by cells for all body functions. Carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids provide this energy. Chemical bonds in molecules of these nutrients contain energy. When the bonds are broken during digestion to form simpler molecules, the energy is released. Energy is measured in units called kilocalories (kcal), commonly referred to as Calories.

Molecules that make up the body are continuously broken down or used up, so they must be replaced. Some nutrients, particularly proteins, provide the building materials for this purpose. Other nutrients—including proteins, vitamins, and minerals—are needed to regulate body processes. One way is by helping to form enzymes. Enzymes are compounds that control the rate of chemical reactions in the body.

Nutrients can be classified in two groups based on how much of them the body needs:

- Macronutrients are nutrients that the body needs in relatively large amounts. They include carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and water.

- Micronutrients are nutrients the body needs in relatively small amounts. They include vitamins and minerals.

Finally, you may not think of water as a food, but it is a nutrient. Water is essential to life because it is the substance within which all the chemical reactions of life take place. An adult can survive only a few days without water.

Water is lost from the body in exhaled air, sweat, and urine. Dehydration occurs when a person does not take in enough water to replace the water that is lost. Symptoms of dehydration include headaches, low blood pressure, and dizziness. If dehydration continues, it can quickly lead to unconsciousness and even death. When you are very active, particularly in the heat, you can lose a great deal of water in sweat. To avoid dehydration, you should drink extra fluids before, during, and after exercise.

Taking in too much water—especially without consuming extra salts—can lead to a condition called hyponatremia. In this condition, the brain swells with water, causing symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headache, and coma. Hyponatremia can be fatal, so it requires emergency medical care.

Suggested Supplementary Reading:

McMillan, T. 2018. How China Plans to Feed 1.4 Billion Growing Appetites. National Geographic. February.

Attribution

Essentials of Environmental Science 9.1 by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from the original by Matthew R. Fisher and Joni Baumgarten.

Essentials of Environmental Science 9.2 by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from original by Joni Baumgarten.