Introduction

Norma Cárdenas

The stereotype of the “traditional” college student is a young white person, age 18-to-24, who lives on campus, by the majority of popular films and college brochures. This stereotype has had negative effects on historically underrepresented college students, making it less likely that they will perceive college as something that can be done. The image of community college is a setting of comedy and it is not “real” college. Community college is looked down as unsuitable for high-wage and white-collar work. Similarly, community college students are perceived as second-rate students, which influences students’ decision to attend community college. Through your enrollment, you will find that postsecondary education, community colleges specifically, creates opportunities and offers a quality education to the community.

Nontraditional college students have debunked the myth that college is only for white, young, middle-class people. For a long time, the admissions criteria at selective colleges and universities was a gatekeeping system where elite students could apply, get into, and afford those colleges. The college cheating and bribing scandal in 2019 revealed the misconceptions about wealth and merit in elite colleges and universities. The unfair system should give us pause to think about access, wealth, and success. Historically underrepresented minority students have been denied access to elite institutions of higher education, despite being worthy and capable. Less than one-half of 1 percent of children from the poorest fifth of American families attend elite colleges and universities. In contrast, enrollment at the 3,250 lowest-funded community colleges and four-year universities is 43 percent Black and Hispanic (The Washington Post: There’s a lot of talk about changing college admissions after the Varsity Blues scandal — don’t hold your breath)

As the college student profile shifts at area colleges and universities, young adults with few responsibilities other than college are becoming a shrinking demographic on many college campuses. Today’s college campuses are increasingly becoming infused with nontraditional students, those 25 and older, with responsibilities beyond the classroom walls. These are not students who transition directly from high school to postsecondary education. Many are first-generation college students whose parents did not attend college and are not providing the student with first-hand information about the inner workings of college. Besides the basic foundational information surrounding college, nontraditional college students need help understanding aspects of college systems and navigating the youth centric culture.

Nontraditional college students are more diverse with work and family obligations. Women students, students of color, student parents, working students, first-generation college students, undocumented/DACAmented students or mixed-status immigration families, queer students, students with a disability, STEM majors, returning students, veteran students, students with intersectional social identities show students do not share a universal experience. While the lived experiences and perspectives of nontraditional college students can be perceived as assets, colleges have not caught up with the changing demographics of their students.

Graduating high school seniors receive support to prepare for college admission. From visiting colleges, attending college-going workshops, test preparation, and coaching for the college application process, college choice, and transition process, these students are primed for college success. For some students, there is a gap between high school graduation requirements and college-readiness standards and career education and training. Undervalued and underserved, students do not have access to college-going guidance and resources at their high schools. For nontraditional students, the complicated language, confusing policies, maze of offices and programs, and cultural isolation make college feel like it is anything other than earned. As nontraditional college students struggle through the confusion, the college experience highlights the differences and skepticism of their place in college.

What Makes A Student Non-Traditional?

The term ‘college student’ is no longer exclusive to the traditional 18-to 24-year-old. The term ‘nontraditional’ is a misnomer since most college students diverge from the traditional path. Nontraditional college students can be broadly defined as having one or more of the following characteristics:

- is 24 years old or older;

- delayed entry to college at least one year following high school;

- has dependents (elder parents, siblings, or other members of the family);

- is a single parent;

- is employed full-time;

- is financially independent;

- is a veteran or member of the armed forces;

- is homeless or at risk of homelessness;

- is an orphan, in foster care, or a dependent or ward of the court since age 13;

- is an emancipated minor;

- is a commuter student;

- is enrolled in non-degree occupational program;

- is attending college part-time;

- has adult learning needs;

- is a GED recipient or Certificate of Completion;

- is a first-generation college student;

- is first-generation in the United States;

- is an English Language Learner; or

- is a dislocated worker

Nontraditional college students do not start at the same place. Nontraditional college students face critical issues surrounding participation in college and ultimately, college success. The critical issues are amenable to change or intervention at various stages in a student’s college life. These critical issues include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Strategies for managing competing time demands;

- Difficulty navigating confusing institutional environments;

- Understanding the culture of college;

- Transitional services for “nontraditional” students;

- Knowledgeable support systems;

- Personal barriers;

- Unpredictable constraints on their schedules;

- Employee enrolled in school priorities;

- Paying for college;

- Membership in professional organizations, practicum placements, or professional licenses; or

- Underprepared foundation skills and remedial education.

It’s okay to feel ambivalent about higher education, its many requirements, and being out of place. Taking your assets and experiences and shaping them into goals and ambitions is necessary. Turning doubt and challenges into opportunities will help to demystify the norms and processes for being a “successful” college student.

Does A Non-Traditional Student Select The Same College Environment As Traditional Student?

Data from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), the primary federal entity for collecting and analyzing data related to education, reported that over 30% of undergraduates are nontraditional students and 58% attended college part-time during the 2019-2020 academic year. According to the Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success (CLASP), 51% of undergraduate students are classified as independent students. You can only qualify as an independent student for federal financial aid (FAFSA) if you are at least 24 years of age (fafsa.ed.gov). Financial independence combined with the growing cost of attending college are leading to a growing number of part-time students enrolled in colleges. Paying for college can be a combination of federal, state or institutional financial aid. Federal Pell Grants are available for up to six years. The GI Bill provides 36 months of education once you begin college.

A 2018 Briefing Paper titled Understanding the New College Majority, from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), revealed that 66% of college students qualified as low income and would have to work to cover direct and indirect college expenses. The data shows that almost half of college students work 20 hours/week or more while balancing their course loads, homework, and meeting family responsibilities. A little more than half of non-traditional students are parents, 60% of single parents are women, and women of color are especially likely to be student parents. As with student mothers, student fathers also struggle with finances and child care.

Research prepared for the National Center for Education Statistics in 2018, Working Before, During, and After Beginning at a Public 2-Year Institution, showed financial independence influences attendance patterns and suggests a trend in college selection by nontraditional students. In the brief, 28% percent of the students employed while attending 2-year college thought of themselves as an “employee enrolled in school” compared with 12% of students at public 4-year institutions. A significant difference between “employee enrolled in school” and “student working to meet expenses” is how they blend work and college attendance. Not surprisingly, “employee enrolled in school” work full-time and attend college part-time; students who work attend college full-time and work part-time.

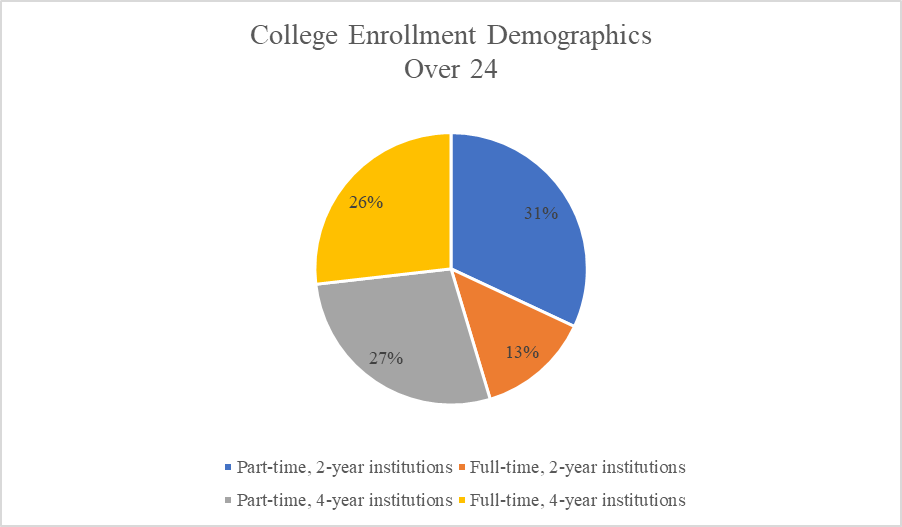

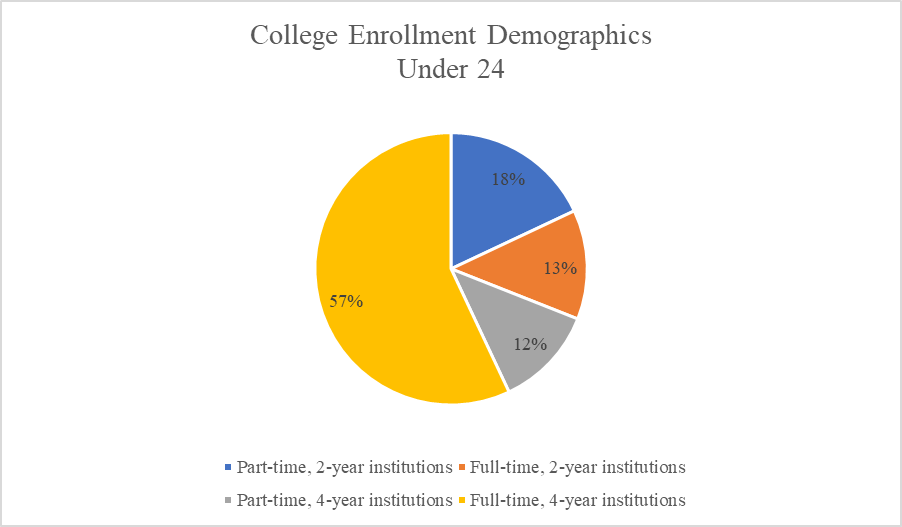

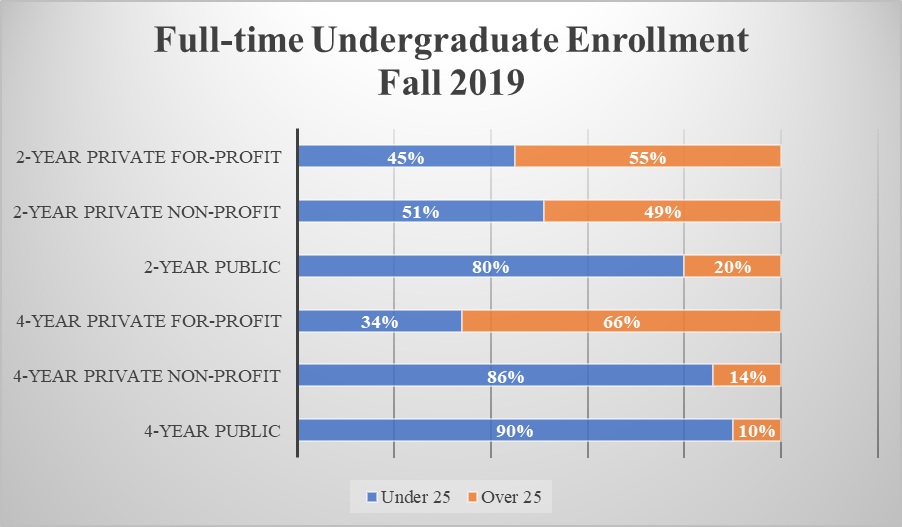

Analyzing the data from NCES on college attendance patterns in the fall of 2019, 4-year colleges, both public and private had over 85% of their full-time student enrollment composed of young adults (under the age of 25). This trend was not true for private for-profit colleges, where young adults represented about 34% of the student population. Students over 24 years old tend to select 4-year private for-profit colleges. At 2-year colleges, the same trend could be seen. Approximately 80% of students attending 2-year public colleges and 51% of students attending 2-year private colleges were young adults and 20% were over the age of 24. Once again, private for-profit colleges were composed of more non-traditional students. Students over 24 years old made up over 50% of their student population.

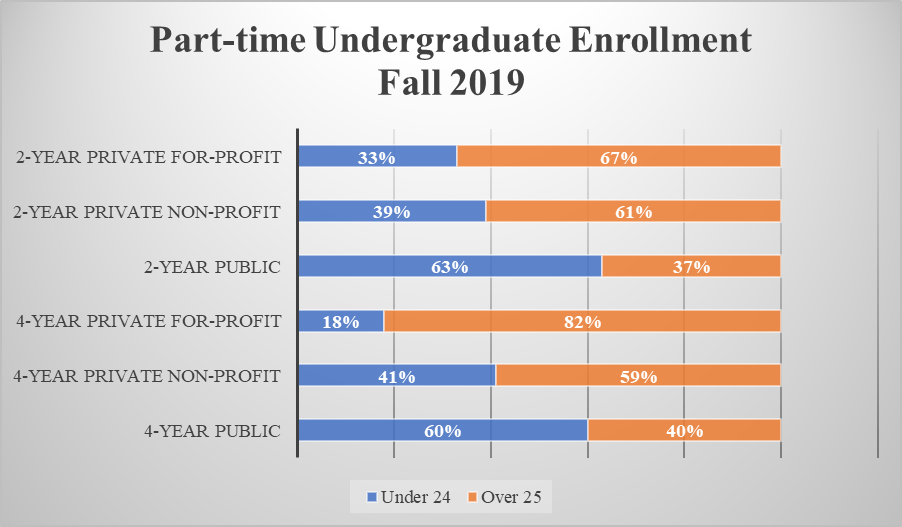

According to NCES data, students over the age of 24 accounted for 40% of the part-time students at public 4-year institutions; nearly 60% of part-time enrollment at private non-profit institutions; and over 80% of part-time students enrolled at 4-year for profit institutions. At 2-year colleges, 37% at public colleges were over 24 years of age. At two-year private colleges, 61% were over 24 years old. At private for-profit 2-year colleges, 67% of part-time students were over the age of 24. Nontraditional college students are concentrated at 2-year public institutions.

Yesterday’s nontraditional students are becoming today’s students and bringing with them a different set of experiences and expectations. Employees-who-study report being interested in gaining skills to enhance their positions or improve future work opportunities as reasons for attending post-secondary education. In the Work First Study Second report, 80% of the employees who work reported enrolling in post-secondary education to gain a degree or credential.

Based on the research, nontraditional students are more likely to display the following preferences/behaviors than traditional students:

- Attend community colleges;

- Work towards an associate degree and vocational certificates;

- Major in occupational fields such as computer science, business, vocational/technical fields; and

- Take fewer courses in behavioral sciences and general education

The nontraditional student population is rapidly becoming the new majority. There is an ever-growing presence of Black and Latinx students, along with those who receive Pell grants at community colleges because of affordability and flexibility. Community colleges are access points with “student-ready” supports and services. However, nontraditional college students do not complete their degrees within six years as well as traditional students. It is highly critical that students receive support from the start of a student’s enrollment in college.

Bridges Not Gates to Completing College

Analysis reveals that the majority of students do not follow the traditional path taking 2 years for an associate degree or 4 years for a bachelor’s degree. Average times to degree are longer because students are starting late, enrolling part-time, changing institutions, or taking stop-outs, often in response to family and work obligations. The Signature Report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center College reports on completion rates. Nearly one in four college graduates complete at a different institution. Part-time students over the age of 24 showed a higher completion rate than did the part-time students in either of the two younger age groups.

The pathways to success are different for every person and affect the time to degree for students at two-year public and four-year public institutions. Redefining success as you navigate higher education is critical. College students attend multiple institutions. Reverse transfers, a student who starts at a 4-year institution then transfers to a two-year, have become more normal. Only one-third of independent students earn a degree or certificate within six years. Independent students are nearly 70% less likely to graduate with a degree or certificate within 6 years of enrolling in college (33 percent versus 56 percent) (IWPR, 2018). Outreach programs and support services such as the federal TRIO program increase college entrance, persistence, completion rates among low-income, first-generation, and students with disabilities. The Beginning Postsecondary Study (BPS) found 9 percent will have attained a bachelor’s degree and 38 percent will have obtained some form of a degree or certificate by 6-years after first enrolling. Another 13 percent will still be enrolled, and 49 percent will not be enrolled and will not have obtained any degree or certificate.

The pathways for students who started at college and stopped out before completing a degree or certificate (Some College, No Credential, SCNC) has grown. Black, Latinx, and Native American learners were over-represented in the SCNC population. While Latinx students are more likely to be enrolled 6 years after enrollment than other groups, Latinx students’ completion rate was 47% compared to 63% for white and Asian students, according to Excelencia in Education (The Condition of Latinos in Education: 2015 Factbook). This does not imply that degree attainment is the only way that students can profit from postsecondary education. Nontraditional students combined work experience and postsecondary course taking to improve their marketability in ways not yet possible for their traditional counterparts who have not begun a career.

Since the pandemic, undergraduate enrollment declined across all institution sectors and for every age group. Public two-year colleges remain the hardest hit sector. Adult students (age 24 and older) saw the sharpest relative enrollment decline this fall. White, Black, and Native American undergraduates declined more than other racial and ethnic U.S. student groups, each falling between 4.4% and 5.1%. Latinx and Asian students fell at about half those rates (-2.4% and -2.2%, respectively).

The pandemic also amplified transfer, financial, scheduling, advising, grading, and pedagogical barriers. The grief and loss of the pandemic took a mental health toll causing students to withdraw or take a mental health leave from college. A few positive outcomes of the pandemic were the increase in online classes for stopped-out students, colleges dropped or made testing optional to address systemic racism within the admission process, and spurred activism on social justice issues.

Why Do The Demographics Matter?

If you talk to people who have gone to college 10, 15, 20, or even 40 years ago, you will hear similar stories about what their college experiences were like. College systems and structural foundations have not changed much from the past. The change that is happening is in the student demographics and their needs/expectations. It is important for students to realize every college has quality programs, culturally responsive services and supports, and its own culture. Finding a comfortable match between student expectations and college expectations is essential for student success. Looking at demographics can help students think about what type of student needs would impact college selection and how that relates to their individual needs. For example, working students may need more flexible course offerings that are online or convenient class times. Students may have work experience or credit transfers to satisfy credentials and finish their degrees. For commuter students, it may be a logistical question of affordable, reliable transportation. In addition, looking at college selection demographics can help prospective students understand there are many roads to college. Employers may offer assistance for tuition, fees, and books. Ultimately, college is a dynamic equation. Recognizing expectations from the student’s needs (financial, admissions, and cultural) and the college’s ability to provide for those needs is a major factor in the student’s college success.

A pathway to college and career success to further Latinx student success is the Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) federal designation, for colleges with a minimum of 25% Latinx student population. According to Excelencia in Education, a Latina-founded and led non-profit organization, HSIs accelerate Latinx student success by addressing students’ intersectional needs, experiences, and identities. Currently in Oregon, three institutions, Portland State University, Western Oregon University. and the University of Oregon, are designated “emerging Hispanic-Serving Institution” (eHSI), where Hispanic students make up between 15 and 24 percent. Another milestone in increasing college graduation is the HB 2871, passed in 2019 by the Oregon legislature, to improve the affordability of course materials and to positively impact student success.

Barriers to College Success

Financial barriers in higher education include tuition and fees, room and board. Navigating the stereotypes, internal fear, self-doubt, and assumptions is part of surviving and a way of life. “Am I supposed to be here?” or “Am I smart enough?”

For students, it may seem like straddling two worlds and feel pressure to assimilate to the middle-class and bridge the gap between college and family. against the cultural values of humility and hard work. Feeling the pull of family responsibility and the push of your studies is difficult to balance. Family and social class plays a role in the academic areas of study the student chooses. For students working part- or full-time, course offerings and sequencing may prevent staying on track. Being overextended limits engagement in group work, co-curricular activities. and study habits. Students face racism and microaggressions and the disconnect between their cultural identities and Western higher education institutions.

With campus navigators, students can access services and talk about workforce needs and educational options. mental-health crisis on campus and the pressure from yourself, family, the cost of higher education (money), and need to finish quickly (time). Finding professors, peers, and mentors who understand and can help create a sense of community is helpful. Through personal connections and networks, knowing how to apply for testing accommodations, picking courses in which you are likely to succeed, are ways to be successful.

Textbook Outline

Our goal in this book is to provide tools and strategies to support college access and success for students. It takes an educational equity perspective and an asset-based framework. The equity framework provides for college access and inclusion and addresses the academic needs of students and the barriers they face. Colleges and universities were not designed with the changing college student population. They shape inequalities students experience. Rather than focus on the assumptions and generalizations that blame students for failing and ignore the circumstances and barriers, an asset-based approach values the strengths of students and focuses on meeting students as capable and deserving of college success and opportunity. Another perspective is a collectivist approach rather than an individualized view of perseverance. No one succeeds alone. To successfully complete college, individual determination is not enough. You will need institutional bridges such as mentors and advisors to navigate the college experience and create a sense of belonging.

The structure of the book follows a life course approach that covers matriculation to graduation: pre-enrollment, matriculation, advising, stress points (first set of finals), orientation, transition (graduation), academic support, advising, campus navigation, time management/study skills, financial aid, and career exploration. We intentionally invite students to look at their own histories, stories, own legacies, and community cultural wealth to prepare you for a college education. Tara Yosso’s (2005) community cultural wealth model focuses on the array of assets nontraditional students possess such as aspirational, familial, linguistic, navigational, resistant, and social capital. Students bring their talents and strengths such as resilience, ambition, and a track record of beating the odds with them to their college environment and then build upon it. The goal of using inclusive language is to affirm race and ethnicity, immigration status, gender and sexual orientation, and ability. We used insights from the authors combined with scholarly sources about word choice.

We hope this blueprint for care contributes to your college success.

Licenses and Attributions:

CC licensed content, Original:

Online Learning: Secrets and Strategies for Success. Authored by: Dave Dillon. Located at: https://www.3cmediasolutions.org/privid/269380?key=c8044911ff1ddafd7c6feaad679d524bffb69ddd License: CC BY: Attribution.

(included in above video): Chem 60 Welcome Video Featuring a Special Guest. Authored by Dr. Benny Ng. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JnBTvVkfZc. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

A Different Road To College: A Guide For Transitioning To College For Non-traditional Students. Authored by: Alise Lamoreaux. Located at: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/collegetransition/front-matter/introduction/ License: CC BY: Attribution.

Adaptions: Curator video removed, reformatted, image removed, “Why I Wrote This Book” relocated to Preface.