10.3 Sexual Attitudes and Practices

Jennifer Puentes and Aimee Samara Krouskop

Attitudes and practices related to sexuality have changed significantly in the past 50 years. In a nationally representative study, Twenge and colleagues (2015) found that people reported more sexual partners, were more likely to have casual sex, and were more accepting of non-marital sex (Twenge et al. 2015). Rather than procreation, individuals think about sex in terms of pleasure (Treas et al. 2014). Research suggests that sexual practices are diverse and discussions of non-normative sexual behaviors such as kink play are on the rise (Wignall and McCormack 2015).

Researchers study sexuality to learn more about how humans participate in the world and identify patterns in both attitudes and practices related to sexuality. As you learned in the last section, the social construction of sexuality enables us to understand how practices that are perceived as normative change over time. Interactions with others, access to education, and policies that shape our social institutions shape our ideas about what behaviors and ideas related to sexuality are acceptable.

Sexuality in the United States

The 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), which was administered to 13,459 Americans ages 15–44 nationwide, provides data about Americans’ sexual behaviors. Research using this survey suggests that although many people think that men are much more sexually active than women, gender differences in heterosexual contact are practically nonexistent (Candra et al. 2011).

Studies show that religiosity is strongly associated with greater disapproval of premarital sex. Sociologists have different measures of religiosity, such as the strength of religious beliefs and how often people participate in religious practices. Research focusing on adolescents finds that those who are more religious are less likely to participate in risky sexual behavior (Landor et al. 2010). Authoritative parenting, affiliation with less sexually permissive peers, and a gendered double standard for daughters also influenced adolescent behaviors.

Survey data on adults produce a similar finding: Among all never-married adults in the General Social Survey, those who reported being more religious were also more likely to have had fewer sexual partners (McFarland et al. 2011). Among never-married adults between the ages of 18 and 39, never-married adults who identified as very religious were more likely to have had no sexual partners in the past five years and, if they had sexual partners it was fewer than their counterparts. Although it is hypothetically possible that not having sexual partners leads someone to become more religious, it is much more likely that being very religious reduces the number of sexual partners that never-married adults have (Smith et al. 2011).

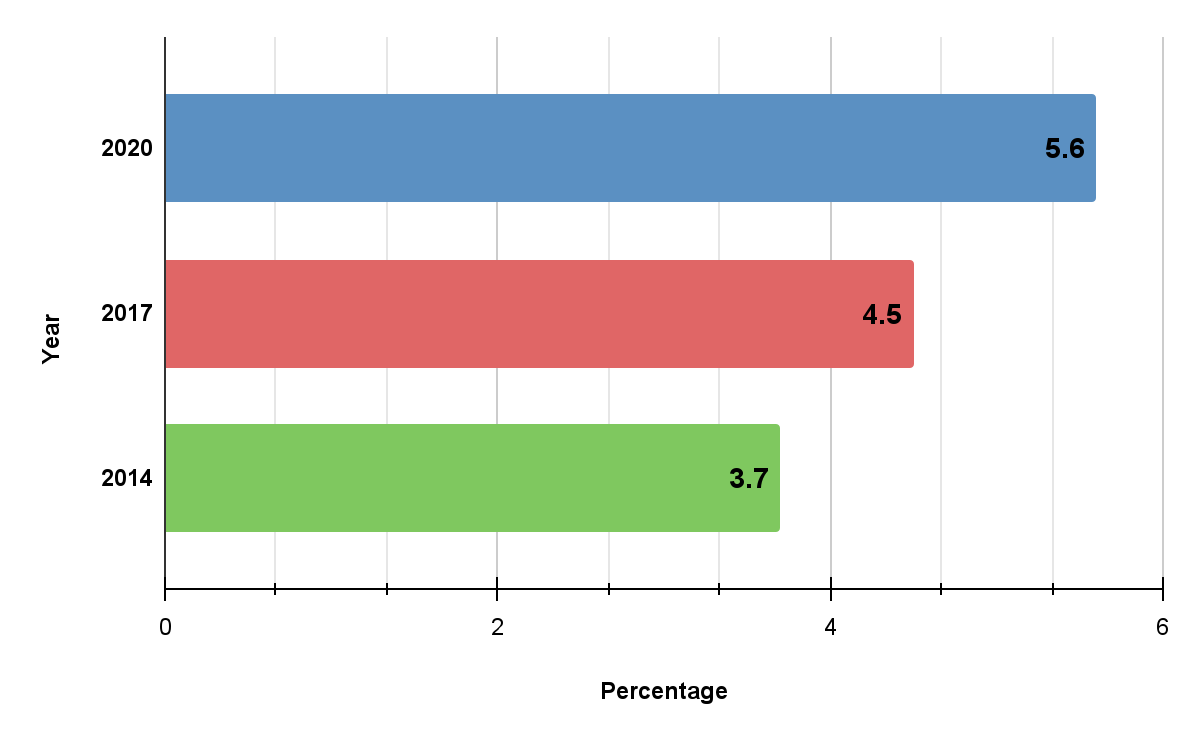

When studying sexuality, sociologists consider more than just sexual behavior. They also examine how people construct their identities. In the United States, the majority identifies as heterosexual (Jones 2021). This majority establishes societal expectations and expressions of sexuality. However, changes are happening, and we are seeing an increase in sexual identities other than heterosexual, as shown in figure 10.3. This shift indicates a potential movement toward a new understanding of sexuality.

Although discrimination and harassment persist today, those who identify as non-straight have gained more visibility and rights compared to 50 years ago. Even so, they remain at high risk of assaults and attacks. Despite this fact, more individuals are willing to openly express their identity, making it increasingly acceptable for others to do the same.

As you learned earlier in this chapter, heteronormativity significantly impacts our current norms and expectations for both gender and sexuality. These ideas have a strong hold on what is accepted, expected, and normalized. The pressure and assumption of heteronormativity can significantly impact many aspects of our society and our own daily lives. The next section will explore the relationship between sexual orientation, privilege, and inequality.

Activity: Changing the Coming Out Narrative to Inviting In

How do gender, sexuality, race, class, and other intersections impact our understanding and experience of the world? Please watch this video from The Root (figure 10.4) and return to answer the questions that follow. Be sure to draw on the material you’ve read in this text as you respond to the questions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdCKe0QBuwQ

- Consider the dynamics and intersections of power and privilege. What impact does that have on your life related to your own sexuality? Or someone you know?

- How do you think these intersections impact sexual attitudes and practices in the United States?

- What would supports and spaces look like if they were informed by intersectionality?

- How might policy changes impact social institutions like workplaces, schools, healthcare? What could this look like on a global scale?

Sexual Orientation and Inequality

Did you know that as recently as 20 years ago, individuals who engaged in consensual same-sex relations could be arrested in many states for violating so-called sodomy laws? The U.S. Supreme Court, which had upheld such laws in 1986, finally outlawed them in 2003 in Lawrence v. Texas by a six to three vote. The majority opinion of the court declared that individuals have a constitutional right under the Fourteenth Amendment to engage in consensual, private sexual activity. Despite this landmark ruling, the LGBTQIA+ community continues to experience discrimination. Sexual orientation is a significant source of social inequality, just as race/ethnicity, gender, and social class are sources of social inequality. Discrimination or prejudice against gay people on the assumption that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation is referred to as heterosexism. In this text, we examine the relationship between sexual orientation and inequalities by focusing on privilege, power, and interactions.

Heterosexual Privilege

Heterosexual privilege refers to the advantages that heterosexuals (or people perceived as heterosexuals) enjoy simply because their sexual orientation is not LGBTQIA+. There are many such advantages, and we have space to list only a few:

- Heterosexuals can be out day or night or at school or workplaces without fearing that they will be verbally harassed or physically attacked because of their sexuality or that they will hear jokes about their sexuality.

- Heterosexuals can express a reasonable amount of affection (holding hands, kissing, etc.) in public without fearing negative reactions from onlookers.

- Heterosexuals do not have to worry about being asked why they prefer opposite-sex relations, being criticized for choosing their sexual orientation, or being urged to change their sexual orientation.

- Heterosexuals do not have to feel the need to conceal their sexual orientation.

- Heterosexuals do not have to worry about being accused of trying to “push” their sexuality onto other people.

Heterosexual privilege can have different consequences in various locations. You will learn more about discrimination and how one’s sexuality intersects with government policy and human rights in Uganda in “A Closer Look: Examining Discrimination Internationally.”

A Closer Look: Examining Discrimination Internationally

In Uganda, legal, social, and professional LGBTQIA+ discrimination has been lengthy and severe. Laws prohibiting same-sex sexual acts were first put in place when Uganda was under British colonial rule in the nineteenth century. After Uganda gained independence in 1962, the laws were retained (Human Rights Watch 2008).

Since then, the LGBTQIA+ community in Uganda has faced widespread discrimination. For example, in 2005, a local tabloid published the names, addresses, and occupations of gay men, putting them at risk for retribution by their employers, family, and neighbors. The paper later threatened to publish a similar list of alleged lesbians (Human Rights Watch 2006). Then, in 2013, the Ugandan parliament passed a bill criminalizing homosexuality and authorizing the government to take children away from LGBTQ parents. In 2014, legislators proposed a death penalty for gay sex (International Rescue Committee 2021). Much of the support for these laws in Uganda comes from fundamentalist Christian religious communities (Harris 2013).

The 2014 proposal was rescinded, in part due to the pressure of local Uganda activists and the international community of human rights organizations. There is some evidence that their work may also be shifting perspectives. A 2013 Pew Research Center opinion survey reported that 96 percent of Ugandans believed homosexuality should not be accepted by society, while 4 percent believed it should (The Global Divide on Homosexuality 2022). But in 2017, a poll carried out by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association found attitudes toward LGBTI people had significantly changed. Fifty-nine percent of Ugandans agreed that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people should enjoy the same rights as straight people, while 41 percent disagreed (ILGA 2016). However, despite this, the international community has been alarmed at laws recently put in place that discriminate against and endanger nonbinary Ugandans.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXmosqvayeM

Please watch this four minute video (figure 10.5), which tells more about the dangers of being gay in Uganda, as well as the spirit of activism countering that discrimination. After viewing, please return to answer the following questions:

- How do social institutions such as government, religion, and family shape the way LGBTQIA+ individuals experience discrimination?

- What other countries have policies similar to Uganda? What does LGBTQIA+ activism look like in those spaces?

Licenses and Attributions for Sexual Attitudes and Practices

Open Content, Original

“Sexual Attitudes and Practices” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Changing the Coming Out Narrative to Inviting In” is adapted from “Why Some Black LGBTQIA+ Folks Are Done ‘Coming Out’” by The Root is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Questions by Jennifer Puentes and Heidi Esbensen are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“A Closer Look: Examining Discrimination Internationally” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is adapted from Fighting for LGBT rights in Uganda [YouTube] by BBC World Service, which is licensed under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The first two paragraphs of “Sexuality in the United States” are adapted from “Sexual Behavior” by Saylor Academy, Social Problems: Continuity and Change, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Modifications include revision by Heidi Esbensen.

“Heterosexual Privilege” is revised from “Inequality Based on Sexual Orientation” by Northeast Wisconsin Technical College, Introduction to Diversity Studies, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Revisions by Jennifer Puentes.

“Sexual Orientation and Inequality” is adapted from “Inequality Based on Sexual Orientation” by Northeast Wisconsin Technical College, Introduction to Diversity Studies, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity by Jennifer Puentes.

Figure 10.3. “Percentage of Americans, 18 or Older, Who Self-Identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender” by Jean M. Ramirez; Suzanne Latham; Rudy G. Hernandez; and Alicia E. Juskewycz in 10.1 Sex, Sexual Orientation and Gender – Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us from Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.4. “Why Some Black LGBTQIA+ Folks Are Done ‘Coming Out’” by The Root is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.5. “Fighting for LGBT rights in Uganda [Streaming Video]” by BBC World Service is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

socially created definitions about the cultural appropriateness of sex-linked behavior that shape how people see and experience sexuality

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privileges heterosexuality over other sexual orientations.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. The additional “+” stands for all of the other identities not encompassed in the short acronym. An umbrella term that is often used to refer to the community as a whole.

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience.

discrimination or prejudice against gay people on the assumption that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation. (Oxford dictionary)

a general term used to describe people whose sex traits, reproductive anatomy, hormones, or chromosomes are different from the usual two ways human bodies develop. Some intersex traits are recognized at birth, while others are not recognizable until puberty or later in life