1.2 What Is Sociology?

Sociology is one of many social sciences that is interested in studying society. In this text, we define sociology as the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions and societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture. Another way to think of sociology is as the systematic study of human society and interactions. Society refers to a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture. All of these definitions emphasize the way that humans are social beings; society and the individual cannot exist without each other.

Sociologists identify and study patterns related to all kinds of contemporary social issues. Examples of topics sociologists might explore include the emergence of new political factions, how X influences everyday communication, the lack of racial and gender diversity in media portrayals of rodeo, and the stop-and-frisk policy. If you want to learn more, you have the option to read about the stop-and-frisk policy [Website].

Social Facts

Some sociologists study social facts—the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life. These practices exist outside of us as individuals, but they still act to constrain our behavior. Social facts make it possible to move beyond studying individuals so we can learn about behavior of entire societies. Social theorist Émile Durkheim (1895) suggested that social facts are concrete ideas that influence the daily life of individuals. Durkheim discussed social facts within the context of kinship and marriage, language, and religion. Another well-known example of Durkheim’s study of social facts examines suicide rates. Using police suicide statistics from different districts, he found patterns that suggest suicide is not solely something that occurs at the level of the individual.

Social facts can refer to material and non-material items (figure 1.4). Material social facts include norms and laws in society that are often observable, such as legal systems. Non-material social facts refer to codes of conduct or best practices. An example of a non-material social fact could be morality or institutionalized religion.

| Examples of Social Facts | |

|---|---|

| Material | Non-material |

| Laws | Norms |

| Art | Values |

| Technology | Practices |

Sociological Perspective

How do sociologists “do” sociology? The first step is to develop your sociological perspective so that you can examine the world around you in a new way. Making the familiar strange enables you to think sociologically. The sociological perspective is a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously. Individuals can act independently within social institutions, but they are also bound by social structures that shape their lives. By becoming a skilled user of the sociological perspective, you will be able to see beyond the outside appearances of the actions of individuals and organizations (Berger 1963).

To develop our perspectives, we might draw from some of the following concepts: beginner’s mind (McGrane 1994), culture shock (Berger 1963), sociological imagination (Mills 1959), and sociological mindfulness (Schwalbe 1998). We will discuss each of these approaches in the next section.

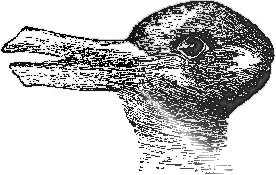

One strategy for developing the sociological perspective involves using the beginner’s mind. The beginner’s mind involves approaching the world without knowing in advance what to expect (figure 1.5). You take on the task of unlearning what you know so that you are open and receptive to the experience of seeing things through a new perspective (McGrane 1994). This concept draws on the Buddhist practices outlined by Shunryū Suzuki, a Sōtō Zen monk and teacher who helped popularize Zen Buddhism in the United States. At the core of this perspective is the idea that the beginner sees many possibilities, while an expert may only see a few possibilities (Suzuki 1970). A novice or beginner may see things with an open mind, setting aside preconceptions about how something should be. For example, a classically trained chef with expert status may believe there is only one correct way to run a dinner service at an event, but a newcomer may challenge this notion in favor of a dining style that reflects the changing desires and needs of current customers. While the expert chef may envision a plated dinner service for a formal event, the beginner’s mind might see value in alternative approaches to dining, such as food stations (enter the innovation of the mac-and-cheese bar at weddings).

Another strategy for developing the sociological perspective is to create a sense of culture shock. Culture shock refers to the experience of disorientation that occurs when someone enters a radically new environment (Ferris and Stein 2018). We can experience new social or cultural environments by first examining our own culture from an outsider’s perspective. The familiar can become strange or new when we take this approach. For example, you may have experienced the feeling of culture shock when you transitioned from high school to college. If you’ve traveled abroad, you may have encountered culture shock as you encountered new foods, languages, and styles of clothing (figure 1.6). You can recreate this feeling by examining your own culture from an outsider’s perspective.

A third approach to developing your sociological perspective is using what sociologist C. Wright Mills calls the sociological imagination, an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. Mills saw the sociological imagination as a way of seeing our own and other people’s behavior in relationship to history and social structure (Mills 1959).

The sociological imagination allows us to understand the relationship between how society influences us and how we can influence society. Typically, people think of their experiences in individualistic terms, meaning they see the impact of their experiences on themselves rather than seeing how our experiences are often shared. The sociological imagination examines how what we are experiencing is connected to larger social patterns and contexts. One illustration of this is a person’s decision to marry. In the United States, we often think of this as an individual choice influenced by feelings like love. However, decisions to marry are also influenced by the social acceptability of marriage and marriage equality. For example, interracial marriages were banned in some states until 1967 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Loving in Loving v. Virginia, determining that laws prohibiting people from marrying outside of their racial background are unconstitutional (for more optional information, see Loving v. Virginia [Website]). You will examine the sociological imagination in greater detail by completing the “Understanding the Sociological Imagination” activity in the next section.

Finally, another way to develop your sociological perspective is through sociological mindfulness. Author and sociology professor Michael Schwalbe uses the term “sociological mindfulness” to refer to how we should develop ways to pay attention to the social world and how it works. Mindfulness entails recognizing how other people might be similar or different from us and how our lives are intertwined with those same people (Schwalbe 1998).

Activity: Understanding the Sociological Imagination

In this short video, you will learn more about C. Wright Mills’s concept of the sociological imagination. To understand and apply this perspective, you will learn how to distinguish between what he refers to as personal troubles and public issues.

Please watch the video in figure 1.7, and answer the following questions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BINK6r1Wy78

- Compare personal troubles with public issues. What example given in the video best helped you distinguish between the concepts?

- Apply the idea of personal troubles and public issues to your own life. List and describe three examples to explain the connection between the concept of personal troubles and public issues.

Licenses and Attributions for What Is Sociology?

Open Content, Original

“What is Sociology?” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.4. “Social Facts” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Last two sentences from “What Is Sociology” are modified from “1.1 What Is Sociology?” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Facts” definition is from Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and brevity.

“Activity: Understanding the Sociological Imagination” by Jennifer Puentes is adapted from “Sociological Imagination” by Sociology Live!, which is licensed CC BY 3.0. Modifications include introduction and questions.

Figure 1.5. The duck-rabbit illusion is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.6. Clockwise from top left: “Compost bin with storage room for extra buckets” by InbalabnI is in the Public Domain; “Traditional style toilet at Hamarikyu Gardens in Tokyo, Japan” by Steven-L-Johnson is licensed under CC BY 2.0; “Aerosan: Low-Cost Sanitation for Emergencies” by SuSanA Secretariat is licensed under CC BY 2.0; “Sanergy- interior of the old toilet model” by SuSanA Secretariat is licensed under CC BY 2.0; “Tahiti, French Polynesia – Le Belvédère” by Matthew Dillon is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.7. “The Sociological Imagination” by Sociology Live! is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among individuals.

the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life. These practices exist outside of us as individuals; instead, these rules act to constrain our behavior.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions.

the legal recognition of the rights of marriage regardless of one’'s sexual orientation or gender identity.