1.3 Examining Diversity

Sociologists are typically concerned with the full range of human experiences. Diversity refers to the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences, that occur among individuals. As we develop our sociological perspectives, we see that human differences exist within systems of privilege and oppression. In these systems, some people in certain social positions are included and gain rewards from the system, and others in different positions are excluded. Privilege is “an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson 2018:148). Privilege exists along a wide spectrum and can include factors like ability, religion, and race. For example, able-bodied privilege allows someone to visit new places without being concerned about accessibility factors like working elevators or ramps. Religious privilege may allow someone to expect that school and work holiday schedules will reflect the holidays they celebrate. People with light skin tones may be able to easily purchase “flesh-toned” items, such as band-aids that reflect their skin tone. You will learn more about privilege in chapters that cover social stratification and class, gender and interaction, sexuality, and race and ethnicity.

In contrast to privilege, oppression refers to a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups (NMAAHC 2019). Sociologists tend to refer to the inequities built into our society as systems of oppression. Some examples can include sexism, classism, ableism, and ageism.

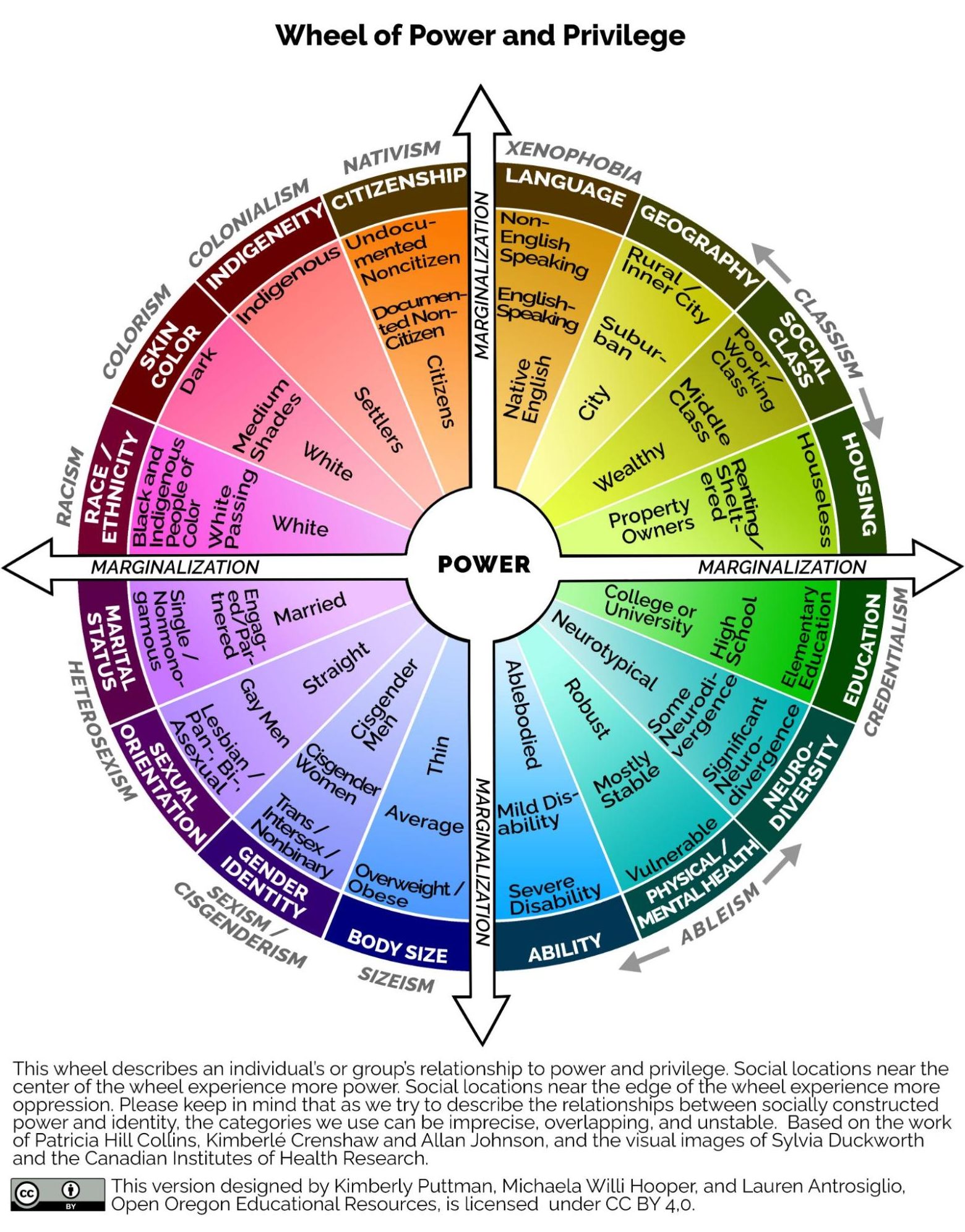

Figure 1.8 offers a visual to help you understand the relationship between identities and social power. Describing just one characteristic of a person’s identity is not enough to understand them. Similarly, understanding any social group requires understanding their complex experiences. For this, we turn to the concepts of social location and intersectionality.

Social location is defined as the combination of various factors, including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location, in relationship to power and privilege (Brown et al. 2019). In the circle in figure 1.8, the word power sits at the center of the circle. People with characteristics near the center of the circle, such as White, non-disabled property owners, have more power and privilege. Power is the ability to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance. People in the center are members of the dominant group.

Non-dominant, or marginalized, groups are located near the outside of the wheel. Marginalization is a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society through the denial of economic and political power (Oxford Reference 2022). People in marginalized groups have less access to power. These social locations may be linked to having only an elementary school education, being houseless, or being queer.

Rather than only being indicators of your identity, these social locations begin to describe the access that people in a group have to wealth, status, political power, economic stability, or other social resources. Identities that align with the groups who have power tend to have privilege. Those identities that align with less powerful groups experience oppression.

Citizens, for example, have the right to vote, the right to safely travel in and out of countries, and the possibility of applying for federal financial aid to finance school. They also have the right to work and receive government benefits like health insurance, social security, and unemployment. Citizenship itself conveys power to that social group. At the far end of citizenship, we find people who are undocumented or living in a country without any citizenship rights. Undocumented people cannot vote, legally enter the country, or receive government aid to pay for education. Undocumented people may be deported at any time. Being safe where you live is a privilege. When you lack this safety, you experience a specific kind of oppression called nativism.

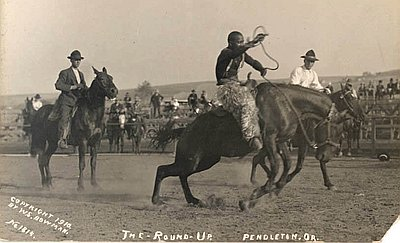

Let’s return to the example we started with at the beginning of this chapter, the Pendleton Round-Up. As you read the next section, “Representations of Diversity at the Round-Up,” reflect on your experiences with rodeos as you analyze representations of race and gender.

Representations of Diversity at the Round-Up: Race and Gender

How does rodeo inform sociologists about group compositions and interactions? Sociologists look for patterns to identify who participates in events and what images become dominant. If we examine the history of rodeos, we see that contemporary events routinely incorporated into Wild West shows, such as roping, controlling, and riding wild bulls and horses, were shaped by Hispano-Mexican techniques of breeding and area games (Fredriksson 1993). What about representation? Who do you visualize when you think of cowboys? Men? Do some racial categories come to mind more than others? The version of the Wild West typically seen through stories and films undercuts the roles of vaqueros, who served as a great influence for what became the American cowboy (figures 1.9, 1.10). On occasions when vaqueros are included, they are portrayed as lazy and untrustworthy (Gandy 2008).

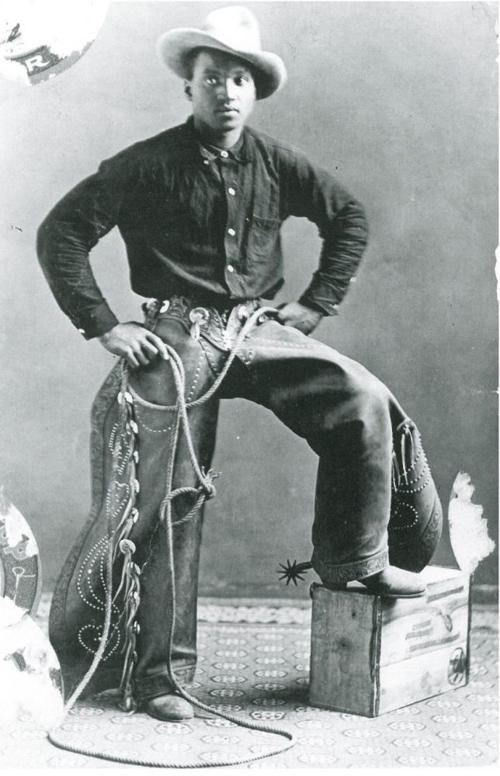

In addition to understanding how groups are portrayed, sociologists are also interested in examining who is not represented. The contributions of Black cowboys are routinely omitted from the myth of the Wild West as well. During the Civil War, as White ranchers went to fight in the war, Black cowboys arrived to take their place. Gandy (2008) suggests that about one in every four cowboys was African American. White and Black cowboys worked together, sharing living quarters and food. However, Black cowboys still experienced social discrimination, which limited employment opportunities and inclusion in some public spaces. Legalized racial segregation in the form of Jim Crow laws in North America led to discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities in society (Patton and Shedlock 2011). You have the option to learn more about Jim Crow laws [Website].

In Oregon, Black cowboys (figure 1.11) brought an element of diversity to rodeos, but unlike other frontier states, few Black cowboys historically lived and worked in the state (Fonseca 2022). Why might this be, when historical documents suggest that in other spaces African Americans held vital roles in building non-Indigenous communities and participating in rodeos? Sociologists want to understand how policies in our social structure and inequalities experienced by groups contribute to demographic patterns.

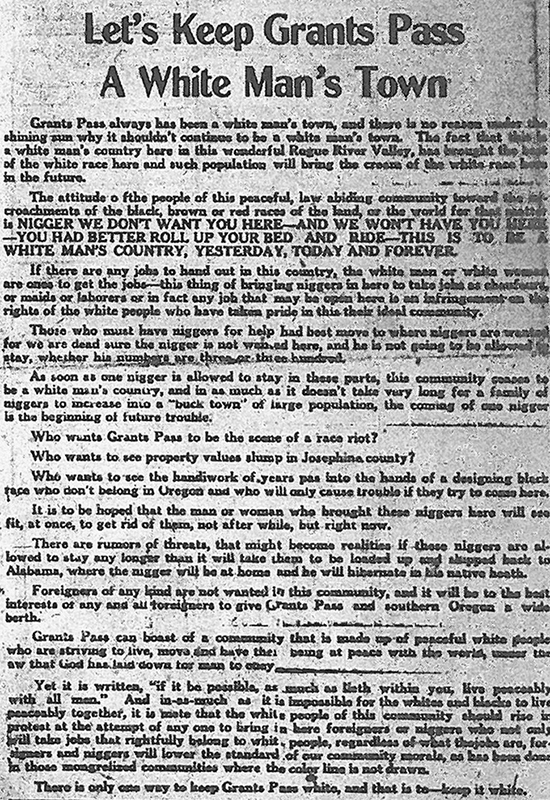

It’s no secret that Oregon had sundown towns, which were almost exclusively White towns with an unspoken rule that it was unsafe for Blacks to live or spend the night there. In the nineteenth century, this residential segregation was reinforced with the use of police, fire, bricks, and unwelcoming signs (Loewen 2005). A 1924 editorial from the Southern Oregon Spokesman explicitly promotes White supremacy (figure 1.12). The author casually and repeatedly uses dehumanizing expletives to refer to African-American people. Further, the author describes African Americans as “a designing Black race who don’t belong in Oregon and who will only cause trouble if they come here” by “lower[ing] the standard of our community morals” and “tak[ing] jobs that rightfully belong to White people.” The author contrasts these racist stereotypes with an idealized description of “peaceful White people who are striving to live, move, and have their being at peace with the world.” You have the option to read more about sundown towns [Website] and unwelcoming signs [Website] if you would like.

At the state level, Black exclusion was written into the law. Only in 2002 did 70 percent of voters decide to remove the racist language from the state constitution (Camhi 2020). However, an examination of historical documents and life histories reveals the importance of Latino vaqueros and Black cowboys in shaping rodeo (Patton and Shedlock 2011). Further, even though there is little visual representation, the way women, Indigenous people, and small-town amateurs embraced rodeo as a sport influenced the organization of events (Mellis 2003) (figure 1.13, figure 1.14).

Gender ideologies connected with the myth of the Wild West also limited representational roles for cowgirls to participate in publicly (Patton and Schedlock 2012). The gendered nature of the organization of the sport inherently prevents women’s participation in professional events (Forsyth and Thompson 2007). However, some roles and spaces are driven by women’s participation. In addition to women’s highly visible roles serving as Rodeo Queen and Princesses or competing in the American Indian Beauty Contest or Junior Indian Beauty Contest at the Round-Up, women provide emotional labor for men who are participating in professional events (figure 1.15, figure 1.16). Acting as a support system or a “helpmate,” women are regularly involved in the activities associated with the Round-Up. Even though their participation may not be directly visible, the roles taken by secretaries, event organizers, wives, fans, and groupies offer the emotional support and financial contributions necessary for rodeos to occur (Forsyth and Thompson 2007).

Licenses and Attributions for Examining Diversity

Open Content, Original

“Examining Diversity” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Examining Diversity” last five paragraphs adapted from “Chapter 2: Who Are We?: Social Problems in a Diverse World” by Kim Puttman in Social Problems 2e [manuscript in press], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: slightly summarized, edited for consistency and brevity.

Figure 1.8. “The Wheel of Power and Privilege” by Kimberly Puttman, Michaela Willi Hooper, and Lauren Antrosiglio, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.10. “Vaquero, c. 1830” is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

Figure 1.11. “George Pendleton Pendleton Round Up Rodeo” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.12. Image from the Southern Oregon Spokesman is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Quarterly.

Figure 1.14. “Cowgirls Hazel Walker and Babe Lee performing a riding trick at the Round-Up, Pendleton, Oregon, between 1912 and 1916” by Walter S. Bowman is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of University of Oregon Libraries Special Collections.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Oppression” definition from Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture is used under fair use.

Figure 1.9. Photo from the Oregon Encyclopedia is included under fair use.

Figure 1.13. “Older woman and child watching festivities at the Pendleton Round-Up” by Ralph I. Gifford courtesy of Oregon Digital is included under fair use.

Figure 1.15. Photograph by The Oregonian/Oregon Live is included under fair use.

Figure 1.16. Photograph by PNG Studio Photography/Shutterstock is included under fair use.

the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among individuals.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

the belief that some individuals or groups are superior to others based on sex or gender.

your position within society. This often includes your position in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, religion, and geography.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

a group that holds the most power in a given society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group.

a term used to describe gender and sexual identities other than cisgender and heterosexual.

the net value of money and assets a person has. It is accumulated over time.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.