10.4 Sexualities: Perspectives and Sociological Research

The study of human sexuality is interdisciplinary and covers a wide range of topics, some of which are the focus of this chapter. You’ve already learned about sexuality, sexual scripts, sexual orientation, and power dynamics associated with heteronormativity. Beyond what we explored, sociologists also focus on identities, bodies, sexual violence, migration/globalization, and sexual politics and social movements. Intersectionality is a useful lens to use when studying sexuality. Social locations like gender and race intersect with one’s experience of sexuality and can impact interactions. Attitudes and practices related to sexuality can inform the structure of social institutions such as work, education, religion, and media. In this section, we focus on sexuality as a continuum and queer theory.

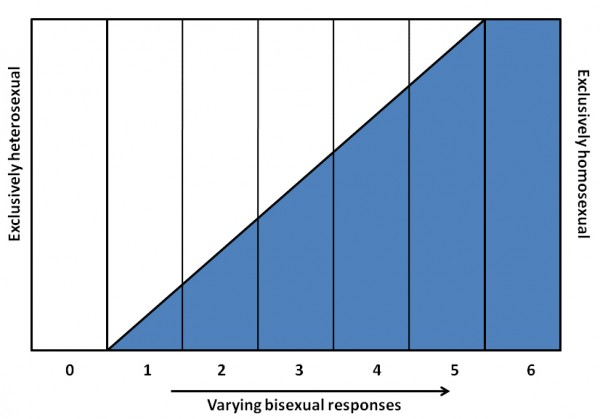

Understanding sexuality as fluid or on a continuum is not a new idea. Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than as a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. He created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual (figure 10.6). For an optional closer look at Kinsey’s research and his contemporaries, you can refer to the Kinsey Institute [Website] at Indiana University.

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual” and to describe nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that U.S. culture influences gendered behavior. Women can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, handholding, and physical closeness. In contrast, men refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative expectation that male sexual attraction should be exclusively for women. Research suggests that it is easier for women to violate these norms than men, because men are subject to more social disapproval for being physically close to other men (Sedgwick 1985). Sedgwick was also one of the founders of queer theory.

Queer theory is a field of critical theory that emphasizes the fluidity of gender and sexualities and the performative qualities of them. It is an interdisciplinary approach to sexuality studies that questions how we have been taught to think about sexual orientation. This theory emerged in the early 1990s from queer studies and women’s studies. The approach problematizes the way Western culture has rigidly split gender and sexuality into specific roles. According to Jagose (1996), queer theory focuses on mismatches between anatomical sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation, and how people cannot just be divided into male/female or homosexual/heterosexual. By calling their discipline “queer,” scholars rejected the effects of labeling; instead, they embraced the word “queer” and reclaimed it for their own purposes. This perspective highlights the need for a more flexible and fluid conceptualization of sexuality—one that allows for change, negotiation, and freedom. This mirrors other oppressive schemas in our culture, especially those surrounding gender and race (Black versus White, man versus woman).

Sedgwick argued against U.S. society’s monolithic definition of sexuality and its reduction to a single factor: the sex of someone’s desired partner. Sedgwick identified dozens of other ways in which people’s sexualities were different, such as:

- Even identical genital acts mean very different things to different people.

- Sexuality makes up a large share of the self-perceived identity of some people, but only a small share of others’ identities.

- Some people spend a lot of time thinking about sex, others little.

- Some people like to have a lot of sex, others little or none.

- Some people experience their sexuality as deeply embedded in a matrix of gender meanings and gender differentials. Others do not (Sedgwick 1990).

Theorists utilizing queer theory strive to question the ways society perceives and experiences sex, gender, and sexuality, opening the door to new scholarly understandings.

Research on human sexuality indicates that there is a connection between power, pleasure, and inequality. The myth of a gendered love/sex binary where men are sexual and women are romantic creates expectations for men to be sexual while women are sexy (Wade and Sharp 2011). This myth is seen in how the media constructs images through an assumed heterosexual male gaze. In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of depicting women from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer. Women are constructed as hypersexualized, passive subjects (Mulvey 1975). Sexual objectification of bodies happens to both men and women in popular culture; however, it is more common to see women’s bodies objectified (Hatton and Trautner 2011; figure 10.7). Research that examines the intersection of power and pleasure highlights gendered inequalities when it comes to sexuality. This section will focus on some of that research by taking a closer look at the orgasm gap, hookup culture, and online dating.

Orgasm Gap

The orgasm gap refers to the difference between reported orgasms by gender. This gap is notably higher in women who have sex with men compared to men who have sex with women (Frederick et al. 2018). According to the 2018 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, which sampled U.S. adults, 91 percent of men reported they had an orgasm during their most recent sexual event. In contrast, only 64 percent of women reported they had an orgasm during their most recent sexual event.

What drives this difference in sexual pleasure? The social factors that are at play, including double standards, sexual norms, scripts, and social pressures, might make this gap seem inevitable, but research shows that the orgasm gap in the United States is twice as large as in Brazil (Beauchamp 2015). Women report their rate of orgasm as being significantly higher when they are without a partner (Kinsey et al. 1953; Harvey, Wenzel, and Sprecher 2004). In a survey with a large U.S. sample of adults, Fredrick and colleagues (2018), found that women’s orgasms were linked to having more oral sex, having sex that lasted longer, and experiencing more satisfaction within the relationship.

The myth of a gendered love/sex binary produces a double standard in which women need to be willing participants in sexual acts, but not too willing. Women attempt to “fulfill” their sexual partner’s needs with minimal focus on their own pleasure. Similar to the sexual norms of satisfying men in U.S. culture, sex is perceived as something for men to enjoy and women to participate in for men’s pleasure. The myth is further perpetuated through pornography, which has become a main source of sex education in the United States. Men and women mirror the sex acts depicted in pornography, many of which are designed to prioritize men’s pleasure (Sun et al. 2014).

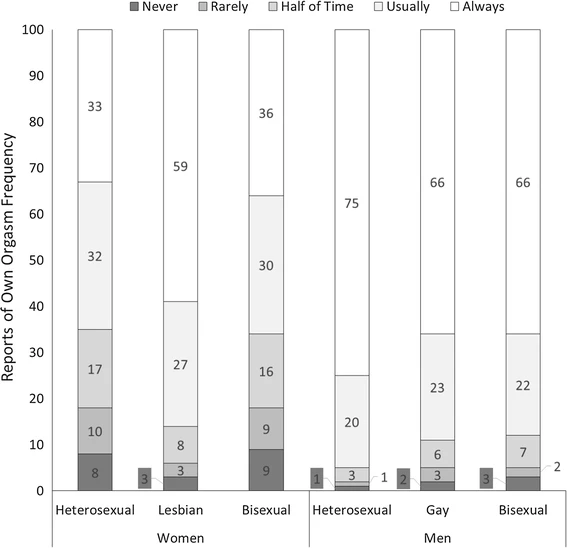

How does this play into LGBTQIA+ relationships? Do the same norms situate themselves within relationships in some way? There is limited research that examines the orgasm gap across the full continuum of sexual identities, but Fredrick and colleagues (2018) make some comparisons across heterosexual men, gay men, bisexual men, heterosexual women, lesbian women, and bisexual women (Figure 10.8). Lesbian women reported more frequent orgasms than heterosexual women, while bisexual women’s experiences were similar to heterosexual women’s. Gay and bisexual men reported similar rates of orgasms compared to heterosexual men; however, they were slightly less likely to always orgasm when sexually intimate. Across this study, men reported more frequent orgasms than women.

Hookup Culture

Hookup culture is when individuals connect for sexual relations outside of romantic relationships. A majority of the research on hookup culture occurs on college campuses or with college age individuals (figure 10.9A and 10.9B). College party scenes tend to center on fraternity houses, where college students under the drinking age can easily access alcohol (Armstrong and Hamilton 2013). Research continues to find that there is a double standard for men and women. Social stigma surrounds women’s sexuality in ways that are restrictive and policed by both women and men (Armstrong, Hamilton, and England 2010; Kettrey 2016; Cera, Ford, and England 2017).

Hookup culture creates gendered expectations for both women and men. These expectations can be identified in research on the orgasm gap, gender differences in initiating hookups, and the double standard. As with the orgasm gap, women report experiencing less physical pleasure from hookups than men do, so the enjoyment of a hookup is gendered in favor of men. Men are also more prone to initiate the hook up and interactions leading up to a hook up.

However, the primary gendered issue with hookups is the double standard we see for women. Social stigmas surround women’s sexuality in ways that are highly restrictive and contradictory. After sexual encounters, men are praised for their actions and for “scoring.” In contrast, women are often criticized and labeled negatively by peers and society regardless of how they handle sexual advances. If they turn down advances, they are called a “prude” or “bitch,” but if they accept advances, they are labeled as “easy” or a “slut.” Recent research on hookup culture shows that women are being criticized less than they were previously, but the stigma and social responses are still frequently negative, regardless of a hookup attempt’s outcome (Armstrong et al. 2014).

Although women are most frequently negatively targeted for their sexual activity, men are not exempt from social censure. In a study of Facebook users, Papp and colleagues (2015) found that men targeted as “sluts” were judged more harshly than women. Future research would benefit from continuing to examine women’s and men’s experiences in a variety of settings, including other social media platforms that might be more popular with younger generations. As you reflect on this section, consider, how does hookup culture inform our social and sexual lives?

Online Dating and the Intersection of Gender, Race, and Sexuality

Today, online dating is accessible and viewed as normative. Currently, over 30 percent of U.S. adults report using online dating sites or apps, and most report having overall positive experiences (Pew Research Center 2020). How does online dating intersect with gender, race, and sexuality?

Data analyzing online dating patterns demonstrates that for Americans, particularly heterosexual people, gender conformity is desirable. The limited research on queer individuals also identifies a connection between gender conformity and sexual desirability. Women looking to date other women have a slight preference for gender-conforming partners (Smith and Stillman 2002), while men looking to date other men have a strong preference for men who embody hegemonic masculinity (Reynolds 2015; Cascalheira and Smith 2020).

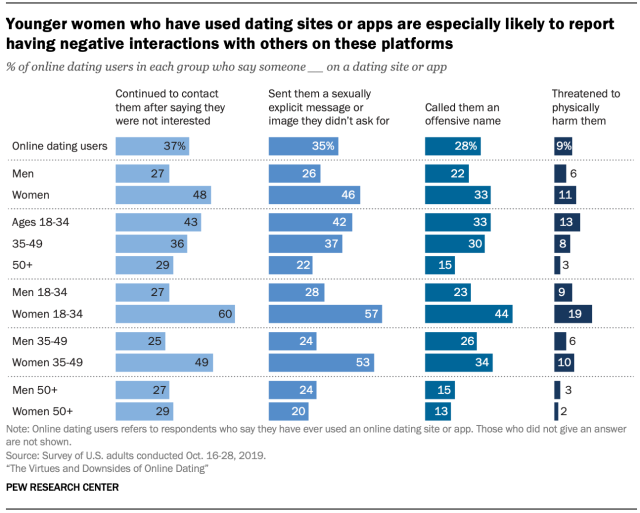

Women’s and men’s experiences with online dating demonstrate differences when it comes to sexual harassment and fear of assault when arranging face to face meetings. Women are more often the recipients of sexually explicit photos and unwanted contact (figure 10.10). Men receive unwanted sexually explicit photos or conversations, but the social norms are gendered and reflect a power dynamic in which unwanted contact with women may lead to fear and concerns for safety. Women are twice as likely to say that they are concerned about their physical and emotional risks in dating (Pew Research Center 2020).

Remember OkCupid? Cofounder Christian Rudder (2014) used online dating profiles to analyze the relationship between gender, race, and sexuality when it comes to partner selection. Racist sexual stereotypes about Black and Asian people influence response rates on dating profiles. For Black men, racial stereotypes have favorable and unfavorable consequences. Being stereotyped as hyper masculine, Black men are seen as especially sexy, sexual, and sexually skilled compared to White men. Though they may be sought out as sexual partners because of these stereotypes, the idea that they are too masculine and too sexual may make them seem like frightening or inappropriate partners. Black men are the least likely to get a response from women and men.

White men have an advantage on dating apps and are more likely to receive responses from people across all racial groups (Curington, Lundquist and Lin 2021). You will learn more about Whiteness and privilege in the next chapter, but an examination of online dating patterns reflects the privilege associated with Whiteness in U.S. culture.

Historically, women of color have been oversexualized and eroticized, which translates into online platforms in multiple ways. Bias and racism underlie comments like “I’m just not into (insert racial identity).” Selecting a partner based on their race is a type of sexual objectification. Like Black men, Black women are among the least likely to receive a response. The racial stereotypes that masculinize African Americans of all genders undermine a Black woman’s value in online dating (Rudder 2014). Changes in culture and how people interact may alter how individuals engage with dating apps and partner preferences.

Dating apps have expanded to reach a broader audience. There are apps for queer women, gay men, trans people, Black people, religiously affiliated, kink, etcetera. Apps like Bumble have been developed to put the “power” in the hands of women as they control who can and can’t message them. Her, Lex, and Grindr are specifically made for lesbian, gay, trans, nonbinary, and queer people and attempt to create a safe and accepting space that may not be accessible in other apps like Tinder, Bumble, Match, and Hinge (figure 10.11).

LGBTQIA+ individuals express a lack of acceptance and report experiencing harassment and hate on the more “traditional” dating sites (Griffins and Armstrong 2023; Pym, Byron, and Albury 2020). The percentage of LGBTQIA+ couples who have met online is higher than for other sexuality groups (figure 10.12). Some evidence suggests that this is due to safety, as well as knowing that the other person would be attracted to you (Byron, Albury, and Pym 2020). Given our cultural adherence to heteronormativity, it might not be clear if someone is interested in someone sexually. Making assumptions about someone’s sexual identity can be dangerous if that person feels that the assumption threatens their desired presentation of self.

Licenses and Attributions for Sexualities: Perspectives and Sociological Research

Open Content, Original

“Sexualities: Perspectives and Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Queer Theory” subsection is from “Theoretical Perspectives on Sex” in Lumen/Openstax Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sexualities: Perspectives and Sociological Research” paragraphs two and three modified from Sexual Orientation by Heather Griffiths et al., Introduction to Sociology 2e, OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Paragraphs four and five adapted from “Sexuality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Male gaze” definition is adapted from Wikipedia and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 10.6. “The Kinsey Scale” from “Sex and Gender” by Heather Griffiths et al., Introduction to Sociology 2e, OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.9, left. “laughing people in party” by Samantha Gades is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 10.9, right. “man in red polo shirt pouring wine on clear wine glass” by Jonah Brown is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 10.12, left. “man in black jacket standing beside man in black jacket” by Kyle Bushnell is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 10.12, right. “woman lying on white bed” by Womanizer Toys is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.7. Photo by Estelle Rodrigues is included under fair use.

Figure 10.8. Graph from Differences in Orgasm Frequency Among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Men and Women in a U.S. National Sample by Frederick, St. John, Garcia, and Lloyd is included under fair use.

Figure 10.10. “Younger women who have used dating sites or app are more likely to report having negative interactions with others on these platforms” by Pew Research Center is included under fair use.

Figure 10.11. Image included under fair use via ctgirlwiththeredscarf.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privileges heterosexuality over other sexual orientations.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a term used to describe gender and sexual identities other than cisgender and heterosexual.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

is a field of critical theory that emerged in the early 1990s out of queer studies and women's studies; it emphasizes the fluidity of gender and sexualities and the performative qualities of them.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

a deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

the act of depicting women from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer.

a theoretical framework that argues women suffer discrimination because they belong to a particular sex category (female) or gender (woman), and that women’s needs are denied or ignored because of their sex.

the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in mainstream society.

the disparity or unequal outcome in orgasms between couples, genders, and sexualities.

a culture in which casual sexual encounters including one night stands, sexual engagements, and so forth are accepted and encouraged.

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. The additional “+” stands for all of the other identities not encompassed in the short acronym. An umbrella term that is often used to refer to the community as a whole.

the masculine ideal that is viewed as superior to any other kind of masculinity as well as any form of femininity.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

a type of prejudice and discrimination used to justify inequalities against individuals by maintaining that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is a set of practices used by a racial dominant group to maximize advantages for itself by disadvantaging racial minority groups.

a social identity ascribed to individuals based on their gender and the gender of the object of sexual desire. Sexuality includes personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.