10.5 Inequalities Experienced through Interactions

Jennifer Puentes and Heidi Esbensen

Members of the LGBTQIA+ community experience discrimination in everyday interactions and a variety of settings, including workplaces, education, and healthcare. Microaggression refers to the commonplace verbal, behavioral, or environmental slights, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes toward stigmatized or culturally marginalized groups (Sue 2010). Microaggressions occur during interactions and can be seen in hateful comments or harassment experienced on the streets, in schools, workplaces, grocery stores, or even sporting events. In the past couple years in Oregon, there have been issues with a high school that threw out racial slurs at a sports game (Manning 2022) and homophobic slurs being used during school board meetings (Portland Tribune 2021). These examples highlight the way that one’s race and sexuality continue to be weaponized during interactions within the community. Furthermore, the intersection of race and sexuality for people of color who are LGBTQIA+ leaves them at higher risk for interactional harassment. In fact, LGBTQIA+ people who are also people of color have higher rates of harassment, assault, and mistreatment in most areas of their lives when compared to their White counterparts (Mahowald 2021). These issues occur throughout all areas of society, including in housing, employment, and the criminal justice system.

Bullying and Violence

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2023), there were 1,132 hate crimes (violence and/or property destruction) based on sexual orientation bias. This number, which includes anti-heterosexual, and anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes, is likely an underestimate because many victims do not report their victimization to the police. Anti-trans and anti-gender-nonconforming hate crimes (identity-based, rather than sexual orientation based) totaled 669. In a Washington state study of school-age youths, researchers found that youth who are gay, lesbian, or bisexual or perceived as LGBTQIA+ are often the targets of taunting, bullying, physical assault, and other abuse in schools (Patrick et al. 2013). Survey evidence indicates that 76 percent of LGBTQIA+ students report being verbally harassed at school, 31 percent report being physically harassed (pushed or shoved), and 12.5 percent report being physically assaulted based on sexual orientation, gender expression, or gender. Over 60 percent of students who were harassed or assaulted did not report the incident to school staff because they did not think the staff would do anything about the behavior (Kosciw, Clark, and Menard 2021).

The bullying, violence, and other forms of mistreatment experienced by gay teens have significant educational and mental health effects. LGBTQIA+ teens are much more likely than their peers to skip school, do poorly in their studies, drop out of school, and experience depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Mental Health America 2011; Choukas-Bradley and Thoma 2022). These mental health problems tend to last at least into their twenties (Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, and Sanchez 2011). According to a 2011 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), LGBTQIA+ teens are also much more likely to engage in risky and/or unhealthy behaviors such as using tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs, having unprotected sex, and not using a seatbelt (Kann et al. 2011).

Ironically, despite the bullying and other mistreatment that LGBTQIA+ teens receive at school, they are much more likely to be disciplined for misconduct than straight students accused of similar misconduct. This disparity is greater for girls than for boys. The reasons for the disparity remain unknown but may stem from unconscious bias against gays and lesbians by school officials (St. George 2010).

As you listen to the video in the next section, start thinking about some of the intersecting experiences one may have and how it shapes their ability to navigate the world around them.

Activity: Violence and Intersecting Systems of Oppression

Please watch this video on anti-violence and how the connections between race, gender, and sexuality are intersecting (figure 10.13). Be sure to come back to answer the questions in this activity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p0-hgvf3XSA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p0-hgvf3XSA

After you watch the video, consider the following questions.

- How does intersectionality apply to your life and the lives of others in your community?

- What steps can we take to recognize power dynamics and change them?

- How does oppression and power connect to the topics we have covered so far? Sex education? Sexuality and heteronormativity?

Sexual Violence

Sociologists examine topics like sexual assault and violence to better understand underlying inequities and how these behaviors are part of our current culture. Language, norms, and everyday behaviors contribute to a culture that permits sexual violence. Sexual violence is normalized through environments that promote an unequal distribution of power and value toxic masculinity. From these environments springs rape culture, which justifies, naturalizes, and may glorify sexual pressure, coercion, and violence (Marcus 1992; Pascoe and Hollander 2016). Rape culture facilitates sexual assault and is perpetuated through the presence of persistent gender inequalities and attitudes about gender and sexuality. As you learned in Chapter 9, gender norms organize social institutions in our society, including power structures and institutional discrimination. Sexuality works to structure our world similarly.

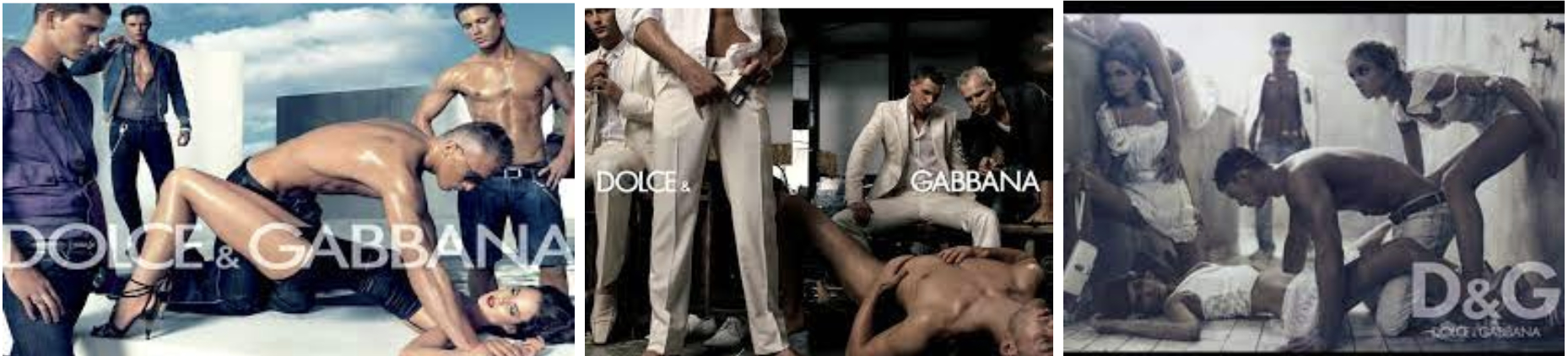

One way rape culture is normalized is through displays of sexual violence in popular culture. Campaigns and advertisements are meant to grab attention, but is there a point at which they can go too far? Please think about these questions as you view the images in figure 10.14. What messages are being conveyed about bodies, gender relations, and consent in these Dolce & Gabbana ads? How do these messages shape our culture? You will learn more about how violence becomes part of our culture in the section “Activity: Understanding the Normalization of Violence.”

In the United States, sexual assault and rape are statistically underreported. The variation in how the data is measured and defined contributes to the significant discrepancies in reported numbers (RAINN 2024). According to RAINN, there are 463,634 reported cases of rape and sexual assault each year involving individuals aged 12 and older. Females are at the highest risk, with a higher percentage of reported and assumed assaults. Males are also impacted, accounting for about 1 out of 10 reported rape victims. Additionally, transgender, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming individuals face a higher risk of rape and sexual assault compared to cisgender men and women.

Another way rape culture is perpetuated is by teaching young girls and women to minimize their discomfort to avoid hostile situations with men to protect themselves. Normalizing this behavior occurs in several ways. For an optional closer look at this topic, read the article “The Thing All Women Do That You Don’t Know About [Website].”

The ideas and norms that are part of rape culture also serve as barriers to reporting sexual violence. In U.S. culture, there is a great deal of uncertainty around the types of consequences perpetrators of sexual violence will experience. Influenced by how the media portrays such cases, people may not report incidents of sexual violence due to fears of not being believed. Concerns include doubts about men’s ability to control themselves, mistrust in authority figures’ responses, embarrassment, self-blame, and lack of support from others. These fears create barriers for survivors seeking help and justice.

Sexual violence is not mainly about sex; it’s more about control and dominance. In situations of sexual assault, sex is used as a weapon to gain power over another person. The images in figure 10.15 show how violence is excused and victims are unfairly blamed. These victims can be anyone.

Research shows that men are also victims of sexual violence, with 1 in 26 men reporting that they suffered completed or attempted rape at some point in their lifetime, compared to 1 in 4 women. In other words, approximately 14 percent of reported rapes involve men or boys, with 1 in 6 reported sexual assaults being perpetrated against a boy, and 1 in 25 reported sexual assaults being perpetrated against a man.

There are many barriers to reporting for women and men. However, for men there is a specific culture of silence that is based on several factors, one of which is personal shame in response to cultural norms of strength and dominance. According to 2015–16 data, 1.3 percent of men reported incidents of being “made to penetrate” in the past year, either through physical force or because of intoxication (Smith et al. 2018). This shows the normalization of sexual harassment and violence as a way for some people to assert dominance and control over others. It also highlights the challenges people face in reporting and dealing with the trauma after such events. Victims often face criticism, rejection, disbelief, and blame and are made to feel like the events they experienced either were not real or were their fault. Others may say or imply that the victim should have been stronger, said no more forcefully, or behaved or dressed differently. Our responses to acts of violence send messages about what types of behaviors and language are acceptable.

Rates of sexual violence in the LGBTQIA+ community are the same or higher than in heterosexuals (Human Rights Campaign 2024). Sexual violence will be experienced by about half of all trans individuals and bisexual women during their lifetimes (Flanders, Anderson, and Tarasoff 2020). Their experiences relate to having higher risk factors such as poverty, stigma, and marginalization. Another factor is hate-motivated violence, which can often take the form of sexual assault and sexual violence. There are also high rates of intimate partner violence and sexual assault by partners within the LGBTQIA+ community (Human Rights Campaign 2024).

Transphobia and homophobia, an extreme or irrational aversion to LGBTQIA+ people, are evident in the rates of sexual assault experienced by transgender individuals, with almost half experiencing such assaults in their lifetime. People who are trans and BIPOC experiencing even higher rates (Griffiths and Armstrong 2023). Another concerning trend is that people identifying with the LGBTQIA+ community are less likely to access services, and if they do attempt to get help, they may be denied services due to their sexual or gender identity (Kumar and Joseph 2021). This lack of access further adds to the barriers faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals. The next section of this chapter will examine a few of the other ways that policies and social institutions create barriers for LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Activity: Understanding the Normalization of Violence

Please watch this video (figure 10.16) on how we can challenge the normalization of violence against women and come back to answer the questions in this activity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBtXiTumdY0

- What was one thing that really stuck out to you about this video?

- Susana Pavlou discusses some myths around sexual violence. Have you heard, witnessed, or experienced these myths in your experiences with society? How prevalent are they?

- What suggestions does the speaker present for decreasing sexual assault? How do you think we can decrease sexual assault?

Licenses and Attributions for Inequalities Experienced through Interactions

Open Content, Original

“Inequalities Experienced through Interactions” by Heidi Esbensen and Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Violence and Intersecting Systems of Oppression” adapted from “Video 1: Connecting the Dots” by Futures Without Violence, licensed under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Questions by Heidi Esbensen and Jennifer Puentes.

“Sexual Violence” by Heidi Esbensen and Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Understanding the Normalization of Violence” adapted from “Challenging normalization of sexual violence against women | Susana Pavlou | TEDxUniversityofNicosia” by TEDx Talks, licensed under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Questions by Heidi Esbensen.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Bullying and Violence” is adapted from “Inequality Based on Sexual Orientation” by Northeast Wisconsin Technical College, Introduction to Diversity Studies, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for consistency and updated by Jennifer Puentes.

Figure 10.15. Clockwise from top left: Image by Staff Sgt. BreeAnn Sachs is in the Public Domain; “SlutWalk DC 2013 [02]” by Ben Schumin is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; “stop women abusing” by Kogulanath Ayappan is licensed under the Unsplash License; Photo by Mart Production is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.13. “Video 1: Connecting the Dots” by Futures Without Violence is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.14. Advertisements by Dolce & Gabbana are included under fair use.

Figure 10.16. “Challenging normalization of sexual violence against women | Susana Pavlou | TEDxUniversityofNicosia” by TEDx Talks is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. The additional “+” stands for all of the other identities not encompassed in the short acronym. An umbrella term that is often used to refer to the community as a whole.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

a term used for commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental slights, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes toward stigmatized or culturally marginalized groups.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

an organization that exists to enforce a legal code, which in the United States includes the police, courts, and corrections system.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

a person whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not necessarily the same.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privileges heterosexuality over other sexual orientations.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a society or environment whose prevailing social attitudes have the effect of normalizing or trivializing sexual assault and abuse.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in mainstream society.

people who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth are often referred to as cisgender, utilizing the Latin prefix cis-, which means “on the same side.”

an extreme or irrational aversion to gay, lesbian, bisexual, or all LGBTQIA+ people, which often manifests as prejudice and bias.

a deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.