10.6 Policies and Social Institutions: Inequalities Experienced at the Structural Level

Jennifer Puentes and Heidi Esbensen

In the last section, we focused on some of the ways people experience discrimination at the interactional level. To gain a better understanding of how inequalities persist at a structural level, let’s take a closer look at a few social institutions, such as marriage and families, healthcare, and workplaces. As you consider the relationship between interactions and social institutions, you’ll see it is nearly impossible to completely disconnect harassment in interactional situations from policies built into social institutions. For example, consider perspectives on heteronormativity and how they influence daily interactions and structures in our society, as well as gender norms and expectations. Those norms influence institutions and policy, both of which are deeply rooted systems with power dynamics based on binaries and patriarchal ideologies.

Families: Marriage Equality

Marriage equality did not exist for same-sex couples until 2015, making this a very recent step toward equality given the historical patterns of the United States. Marriage equality refers to the legal recognition of the rights of marriage regardless of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity. For a long time, legal marriage was not a possibility for everyone. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution in Loving v. Virginia. Forty-eight years later in 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that the Fourteenth Amendment requires all states to grant same-sex marriages and recognize same-sex marriages granted in other states. You will learn more about this important decision in “Activity: Same-Sex/Same Gender Marriage.”

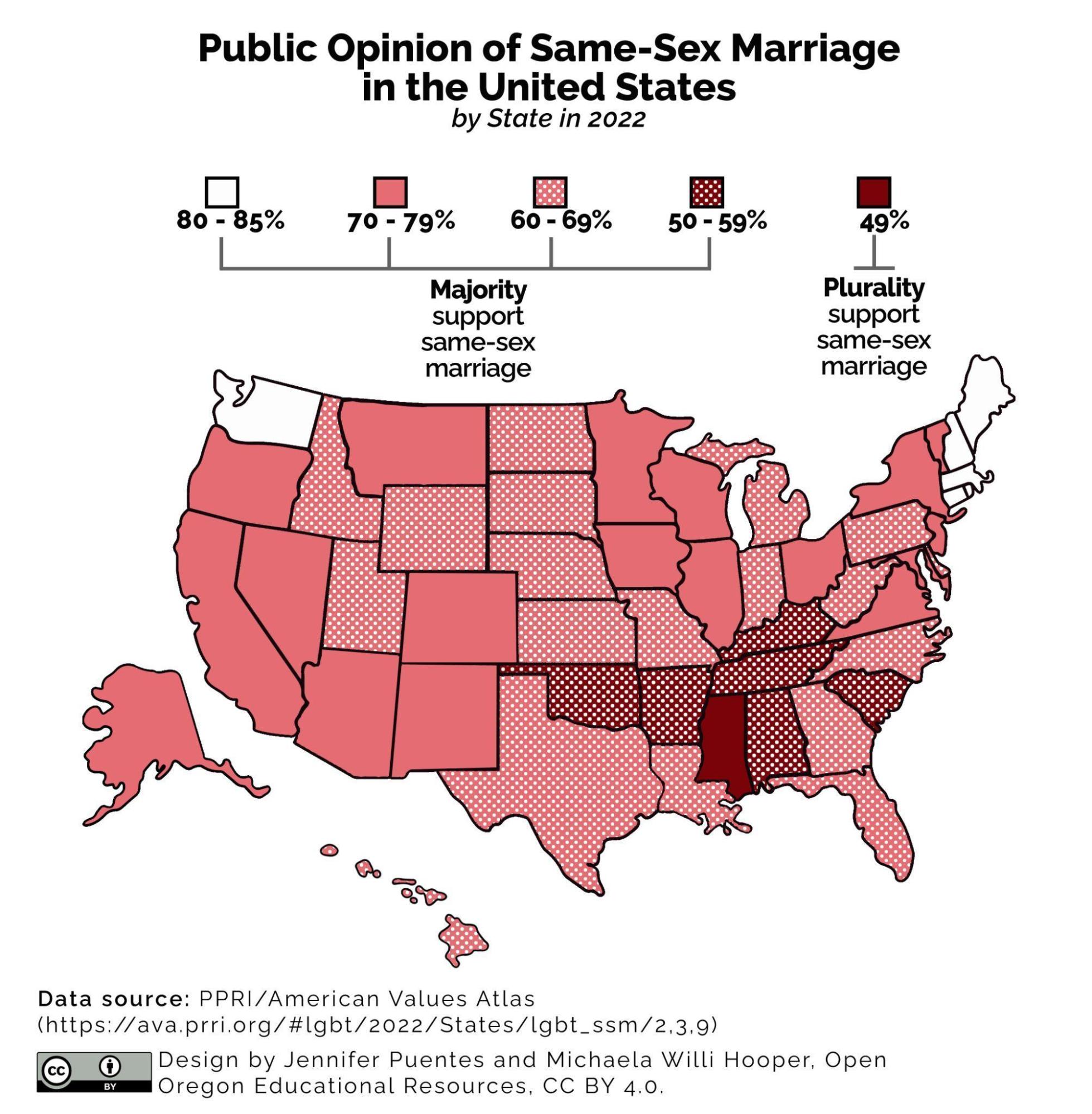

Prior to the Supreme Court ruling, same-sex marriage was legal, but only in certain states, and legal rights were not guaranteed federally. Massachusetts was the first state to grant same-sex marriages in 2004. Congress recently passed the Respect for Marriage Act, which allows recognition of all marriages in all states but does not necessarily protect same-sex marriage if the Supreme Court overturns Obergefell. If you’d like to learn more, you can read about what the Respect for Marriage Act [Website] means. However, in light of Roe v. Wade being overturned, there are still concerns about the possibility of the Supreme Court overruling Obergefell, which would be catastrophic for the LGBTQIA+ community (Webber 2022). According to recent Gallup polls, overturning the Marriage Equality Act goes against public perspectives as most Americans support gay marriage by a significant percentage (figure 10.17).

If you’d like more information and data on same-sex marriage and public opinion, you can review this recent Gallup poll [Website].

Activity: Same-Sex/Same-Gender Marriage

The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges created equal access to marriage for gay men and women in 2015. To learn more about this decision, please watch the video (figure 10.18) and answer the questions that follow.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymrzc7a_LmU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymrzc7a_LmU

- What has made our society limit who can access the benefits of marriage?

- The four dissenting judges cited that states should independently decide whether the state should allow same-sex marriages based on popular votes. What effects do you think this would have federally? What about in states that would vote no?

- After the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, decisions about abortion access are left up to individual states. What rights would same-sex couples lose if some states decided their marriage was illegal? How does the Respect for Marriage Act support couples?

Education: Sex Education in the United States and Abroad

Sex education in U.S. classrooms continues to be a controversial topic. Unlike many other countries, sex education is not required in all public school curricula in the United States. Should sex education be taught in school? Research indicates that only 7 percent of U.S. adults oppose sex education in middle schools, and 4 percent of parents oppose sex education in high schools (Planned Parenthood 2024). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advocates in favor of children and adolescents having access to developmentally appropriate, evidence-based education. Specifically, the AAP stresses the importance of youth developing a safe and positive view of sexuality, learning how to build healthy relationships, and learning how to make informed choices about their sexuality and sexual health (American Academy of Pediatrics 2024). Given this, what are people debating about sex education?

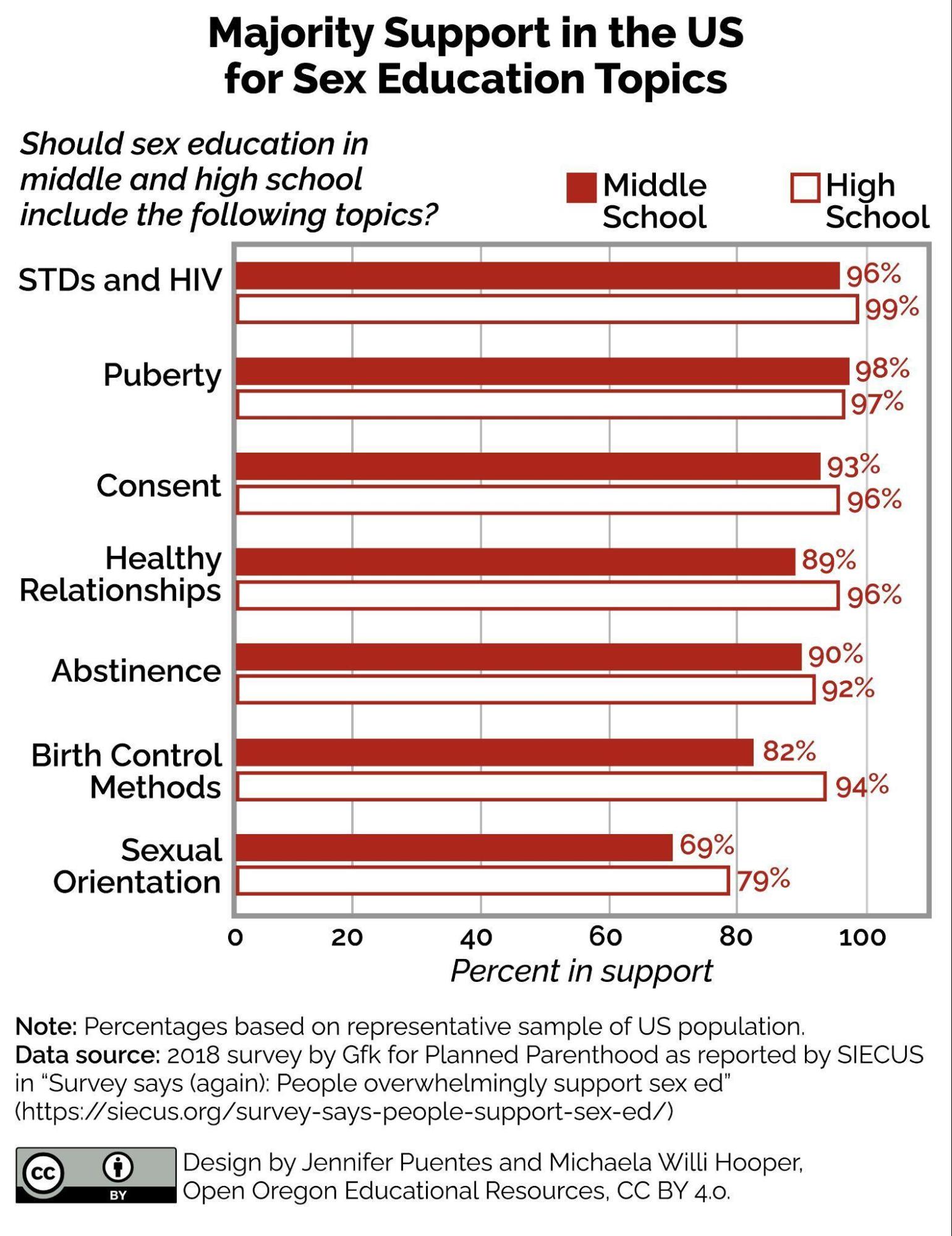

Much of the debate is over the issue of abstinence. Abstinence-only programs or “sexual risk avoidance” programs focus on avoiding sex until marriage and/or delaying it as long as possible. This form of education does not focus on the prevention of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. As a result, according to the Sexuality and Information Council of the United States, only 38 percent of high schools and 14 percent of middle schools across the country teach all 19 topics identified as critical for sex education by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Janfaza 2020). The lack of access to sex education in schools does not reflect parents’ attitudes on the topic. Figure 10.19 outlines U.S. adults’ attitudes about what content should be included in a comprehensive sex education program.

Research suggests that while government officials may still be debating about the content of sexual education in public schools, the majority of U.S. adults are not. Two-thirds (67 percent) of Americans say education about safer sexual practices is more effective than abstinence-only education in terms of reducing unintended pregnancies. A slightly higher percentage—69 percent—say that emphasizing safer sexual practices and contraception in sexuality education is a better way to reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) than emphasizing abstinence (Davis 2018).

Furthermore, research suggests that abstinence-only or sexual risk avoidance education programs do not work (McCammon 2017). Yet despite this research and the clear majorities in favor of comprehensive education, the federal government offers roughly $110 million per year to communities for abstinence-only and sexual risk avoidance programs (Planned Parenthood Action 2024). Decisions regarding guidance on what should be included in sex education are made at the state and local level. Currently, 39 states require discussions of HIV and/or sex education in schools, but fewer than half require the education to be medically accurate (Planned Parenthood Action 2024).

Sweden, whose comprehensive sex education program in its public schools educates participants about safe sex, can serve as a model for this approach. In 2020, the teenage birthrate in Sweden was 5 per 1,000 births (worldbank.org 2020), compared with 15.4 per 1,000 births in the United States (CDC 2021). Among 15- to 19-year-olds, reported cases of gonorrhea in Sweden are nearly 600 times lower than in the United States (Grose 2007).

A sociologist using the sociological perspective would want to look at the correlation between sex education curriculum and outcomes such as teen pregnancies and STIs. Mississippi has the highest rates of teen pregnancy with 28 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 19. Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alabama are next in line with around 25 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 19 (CDC 2021). What does sex ed look like in those states? Is there a correlation? What other factors could influence teen pregnancy in these states?

Healthcare: Physical and Mental Health Stressors

Healthcare is a critical part of how societies organize and respond to the health needs of their members. Individual health and access to healthcare are often influenced by a variety of factors, including one’s ethnicity, race, class, gender, and sexuality. Affluent or wealthy individuals have significantly higher life expectancies when compared to individuals with fewer economic resources (Chetty et al. 2016). For folks who identify as LGBTQIA+, in addition to any concerns or stigma they may have regarding the services they need to seek from a healthcare provider, they may also experience harassment or discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) racked the LGBTQIA+ community beginning in the 1980s. Many gays and lesbians eventually died from AIDS-related complications. HIV and AIDS remain serious illnesses for gays and straights alike. An estimated 1.2 million Americans now have HIV, and about 35,000 have AIDS. Fortunately, HIV can now be controlled fairly well by appropriate medical treatment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011).

LGBTQIA+ adults have higher rates of other physical health problems and mental health problems than heterosexual adults (Frost, Lehavot, and Meyer 2011; Institute of Medicine 2011). These problems are thought to stem from the stress that the LGBTQIA+ community experiences from living in a society in which they frequently encounter verbal and physical harassment, job discrimination, and lack of equal treatment to the point where some feel the need to conceal their sexual identity. Earlier in this chapter, you learned that LGBTQIA+ youth experience various kinds of educational and mental health issues because of the mistreatment they encounter. By the time LGBTQIA+ individuals reach their adult years, the various stressors they have experienced have begun to take a toll on their physical and mental health.

Because stress is thought to compromise immune systems, LGBTQIA+ individuals generally have lower immune functioning and lower perceived physical health than straight individuals. Because stress impairs mental health, they are also more likely to have higher rates of depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, and other psychiatric and psychological problems, including a tendency to attempt suicide (Sears and Mallory 2011). Among all LGBTQIA+ individuals, those who have experienced greater levels of stress related to their sexual orientation have higher levels of physical and mental health problems than those who have experienced lower levels of stress. It is important to keep in mind that these various physical and mental health problems do not stem from an LGBTQIA+ sexual orientation in and of itself, but rather from the experience of living as an LGBTQIA+ individual in a homophobic society.

Workplace Practices and Policies

Research on gender and racial/ethnic labor force inequality uncovers disadvantages experienced by LGBTQIA+ individuals. Inequalities take the form of exclusionary policies, discriminatory hiring and promotion practices, and biased interpersonal interactions (Patridge, Barthelemy, and Rankin 2014; Ragins and Cornwell 2001; Tilcsik 2011). Workplace heteronormativity and heterosexism contribute to disadvantages experienced by LGBTQIA+ workers (Collier and Daniel 2017; Tilcsik 2011). In the workplace, almost half of LGBTQIA+ individuals reported some form of discrimination in the year 2019–2020 (Sears et al. 2022). LGBTQIA+ workers are often excluded from benefits and protections extended to their non-LGBTQIA colleagues (HRC 2021; James et al. 2016). Research documents a wage penalty for gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual workers (Mishel 2016; Mize 2016). The lack of enforcing legal protections leaves members of the LGBTQIA+ community at risk.

In addition to formal processes of discrimination, biased interpersonal interactions create challenges in the workplace. One’s sexual orientation, or even presumed orientation based on gender expression, could be used against them by their employer (figure 10.20). Interactionally, LGBTQIA+ employees may experience marginalization in workplace social networks (Connell 2015). As an additional form of labor, workers engage in “status management” as they negotiate when, to whom, and how to disclose information about their identities at work (Jones and King 2014), or make the decision to conceal their identities as a way to minimize bias (Giuffre, Dellinger, and Williams 2008)

The structure of work tasks within organizations may impact LGBTQIA+ workers’ experiences of marginalization and devaluation. Research examining the work organization at NASA found that the project-based teams had less inclusive and respectful interactions with co-workers since workers have to become familiar with new management strategies as they move teams. LGBTQ professionals were more likely to report marginalization in project-based teams. LGBTQ professionals were better able to navigate management styles and build trust in the traditional unit-based structure at NASA (Cech Waidzunas 2022). This demonstrates how work structure directly impacts workers’ experiences with workplace inequality.

Licenses and Attributions for Policies and Social Institutions: Inequalities Experienced at the Structural Level

Open Content, Original

“Policies and Social Institutions: Inequalities Experienced at the Structural Level” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Families: Marriage Equality” by Heidi Esbensen and Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Same-Sex/Same Gender Marriage” is adapted from “Obergefell v. Hodges Explained” by Zack Attack, licensed under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed CC BY 4.0. Modifications include framing activity and authoring questions.

“Workplace Practices and Policies” by Jennifer Puentes and Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.19. “Majority Support in the US for Sex Education Topics” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from GfK for Planned Parenthood, as reported in “Survey says (again): People overwhelmingly support sex ed” by SIECUS.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Education: Sex Education in the United States and Abroad” is adapted from “Sexuality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Updated and edited.

“Education: Sex Education in the United States and Abroad” is adapted from “12.2.11 Sex and Sexuality” by OpenStaxCNX in SOC 300: Introductory Sociology (Lugo), LibreTexts, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

“Healthcare” adapted from “Inequality Based on Sexual Orientation” by Northeast Wisconsin Technical College, Introduction to Diversity Studies, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications include authoring first paragraph and editing for clarity and consistency by Jennifer Puentes.

Figure 10.20. “A non-binary person writing in a notepad” from The Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.18. “Obergefell v. Hodges Explained” by Zack Attack is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

an ideology and a set of institutional practices that privileges heterosexuality over other sexual orientations.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

the legal recognition of the rights of marriage regardless of one’'s sexual orientation or gender identity.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

a deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.

an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. The additional “+” stands for all of the other identities not encompassed in the short acronym. An umbrella term that is often used to refer to the community as a whole.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously.

when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable, but does not necessarily indicate causation

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a social identity ascribed to individuals based on their gender and the gender of the object of sexual desire. Sexuality includes personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

discrimination or prejudice against gay people on the assumption that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation. (Oxford dictionary)