11.3 Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

Jennifer Puentes; Matthew Gougherty; and Nora Karena

Contemporary sociologists reject the argument that race is rooted in biology and have devoted decades of sociological research to understanding how race is socially constructed. According to German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1911), “The existence of any pure race with special endowments is a myth, as is the belief that there are races all of whose members are foredoomed to eternal inferiority” (figure 11.3). In the following sections, we’ll explore a variety of theories used to understand race. First, we will examine the role of pseudoscience in understanding racial categories, before moving on to theories that challenge some initial constructions of race and difference.

“Science” and Social Theory

Thanks to Charles Darwin’s work on natural selection, early European scientists came to accept that all humans descend from a common ancestor and therefore are the same species. However, the misleading racial categories outlined by Blumenbach endured and created the false assumption that race was a biological phenomenon. The superiority of the White race was accepted by early scientists and social theorists. This led them to believe that race was rooted in biology and that White people were “naturally” superior, even as they struggled to understand and describe the origins of social inequality.

Many scientists and social theorists doubled down on biological race by way of social Darwinism. This worldview combines Darwin’s ideas about biological evolution with unsupported theories that race is genetically determined and can therefore be selected for through breeding. During the late 1800s, eugenics was a pseudoscientific political project to “improve humanity” through selective breeding of the “best” specimens of White humans. Eugenics lent a veneer of scientific legitimacy to Hitler’s racist campaign of genocide in Europe. In addition, eugenics undergirded the forced sterilization by the U.S. government of women of color, mostly Indigenous and Black women, who were seen as unfit mothers. Even with these faulty and problematic foundations, eugenics and biological race were also widely accepted in the United States for much of the twentieth century.

Emancipatory Theories

The anthropologist Franz Boas began to question commonly held ideas about biological race and European racial superiority while working with Inuit people on Baffin Island in 1883. He developed the theory of cultural relativism, which asserts that the differences between groups of people were culturally determined and could only be understood by considering specific cultural and historic contexts. Throughout his career, Boas challenged racism with rigorous social science. Despite his broad impact in the field of cultural anthropology, the biological basis for race remained a basic assumption of physical anthropology until the 1960s (Caspari 2003).

In his classic 1903 sociological text, The Souls of Black Folks, W. E. B. Du Bois—you met him in Chapter 2—theorized about racial identity. Du Bois posed a provocative question, “How does it feel to be a problem?” Starting with his own childhood experience of being excluded and treated differently by children who were White, he describes a growing awareness of his racialized identity and of how racial identity connects to meaning, power, and social consequence (figure 11.4). His groundbreaking field research described the harsh economic and social consequences of racial segregation, including extreme poverty, exploitation, and alienation.

Du Bois also described the “spiritual strivings” of an enduring human community subject to the harsh impacts of a racist state. He celebrated the agency, beauty, and inherent human dignity of people who are Black and of the Black community. His research demonstrated that the problem is not Black folks, the problem is racism, which he described as “the color line.” He urgently invited White people to look through the veil of racism that divides us. Aldon Morris, a Du Boisian scholar, argued that The Souls of Black Folks was an early iteration of #BlackLivesMatter (Morris 2017).

Critical Race Theory

Critical race theory is an intellectual and social framework that examines how racism is embedded in American social life through its systems and institutions. This theoretical framework emerged from the intellectual and social movements of civil rights scholars and activists who want to examine the intersection of race, society, and law. In this framework, race is a social construct, something that changes depending on the social and political conditions of the society at a particular point in time. The framework centers on the knowledge and experiences of people of color and points to how they intersect with other identities, such as gender and sexuality.

A Closer Look: Race, Institutions, and Housing

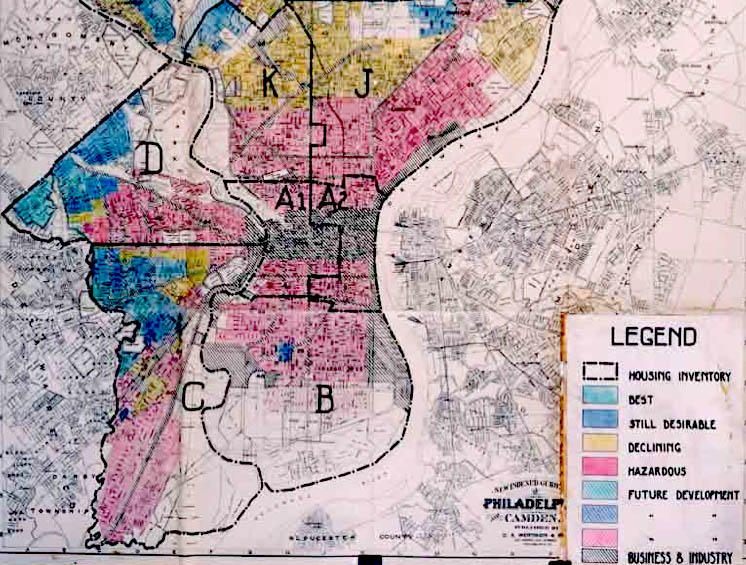

As an example of how racism is embedded in institutions, let us consider race in relation to housing patterns and changes in law. Housing segregation refers to residential segregation or the grouping of people in residential areas by a defining characteristic such as age, socioeconomic status, religion, race, or ethnicity. In the United States, the government and banking institutions have played a role in racial housing segregation through discriminatory practices such as redlining (figure 11.5).

Redlining is the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable or racially occupied. Although homeownership became an emblem of American citizenship and the American dream during the twentieth century, Black people and other nationalities were specifically limited in their abilities to purchase homes (figure 11.6). Both the federal government, which created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933 and the Federal Housing Association (FHA) in 1934, and the real estate industry worked to segregate Whites from other groups to preserve property values.

Lending institutions and the federal government did this by creating maps in which the places where people of color and/or foreign-born individuals lived were colored red or yellow. Then those areas were designated to be “dangerous” or “risky” in terms of loaning practices.

It was then less likely that loans with favorable terms could be secured in the red and yellow neighborhoods. As a result, because Black and foreign-born families were often denied access to the neighborhoods designated to be “good” or “the best,” they were forced to take loans that required higher down payments and/or higher interest rates. Unscrupulous private lenders used this opportunity to create unfair practices, often with devastating consequences for missed or partial payments, such as the homeowner losing their home and all equity that had been earned (Coates 2014).

In 1968, these practices were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act, which was part of the Civil Rights Act. The Fair Housing Act is an attempt at providing equitable housing to all. Still, much damage was done before its passage. For decades, the federal government poured tax monies into home loans that almost exclusively favored White families. Home ownership is the most accessible way to build equity and wealth, and it was denied to many minority families for decades. Even after the Fair Housing Act passed, local governments, residential covenants, and deed modifications continued to discriminate well into the 2000s, and families in minoritized groups still had less success in achieving home loans.

The result of these institutionalized efforts resulted in residential segregation, the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods. Many times this is associated with race, but it can also be associated with income. Segregated neighborhoods did not come about organically but through deliberate planning of policies and practices that have systematically denied equal opportunity to minority populations. Segregation has been present in the United States for many years, and while now it is illegal, it has been institutionalized in neighborhood patterns. From information collected in the 2010 census, we see that a typical White person lives in a neighborhood that is 75 percent White and 8 percent Black, while a typical African-American person lives in a neighborhood that is 35 percent White and 45 percent Black (Frey 2020).

Racial Formation Theory

Racial formation theory refers to the fact that society is continually creating and transforming racial categories (Omi and Winant 1994). For example, groups that were once self-defined by their ethnic backgrounds (Mexican American, Japanese American) are now racialized as “Hispanics” and “Asian American.” The notion of racial formation points to how what we define as race varies and changes as political, economic, and historical contexts change. In other words, different race classifications arise at particular places and at particular points in time.

As examples, we can look at several Supreme Court decisions around a century ago that quickly changed the definitions of race, which at that point was important for determining citizenship. In Takao Ozawa v. United States, Ozawa argued that Japanese people should be classified as White and allowed to become citizens. The Court unanimously argued that White people were part of the Caucasian race and Japanese people were not White. Three months later in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, Thind argued that Indians and Europeans shared common ancestry, therefore making Indians part of the Caucasian race and eligible for citizenship. This time the Supreme Court argued that Whiteness was not something that could be scientifically defined, but was based on the “common understanding” of White people. The court ruled that Thind was not White using that standard and thus not eligible for citizenship. Considering what you’ve learned in this chapter, how might the Supreme Court’s decision to link a “common sense” definition of Whiteness to one’s ability to become a naturalized citizen create legislative discrimination?

For more about the social construction of race, revisit What Is Race? earlier in this chapter.

Colorblindness/Theory of Racial Ignorance

Colorblindness, or colorblind racism, is a form of racism that is hidden and embedded in our social institutions. The notion that one “does not see color” is problematic and serves to erase the experiences of racial and ethnic minority groups. The United States cultural narrative that typically focuses on individual racism fails to recognize systemic racism. Colorblind racism has arisen since the post-civil rights era and supports racism while avoiding any reference to race (Bonilla-Silva 2015).

The theory of racial ignorance explains how racial ignorance (“I don’t see color”) reinforces White supremacy, the belief that White people are better than other races. Racial ignorance is built into the core of racialized social systems and leads to the reproduction of inequalities (Mueller 2020). Colorblindness or claiming racial ignorance is problematic at both individual and structural levels. At the level of the individual, White ignorance refers to a person’s willful ignorance of racial injustice. From a structural perspective, racial ignorance develops from a process that systematically perpetuates racial injustice. The structuralist view allows us to identify patterns of ignorance that contribute to White racial domination. By examining racial ignorance as a structural problem, we can begin to work toward building equity (Martín 2021).

Intersection Theory

Feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) (figure 11.7) further developed intersection theory, originally articulated in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw (figure 11.8), which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes. You previously learned about this theory in Chapter 2 and Chapter 9. When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped by other factors, such as our gender and class. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a White woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on an Asian woman in poverty, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and being Asian.

Postcolonial Theory

Postcolonial theory explores colonial relations and their aftermath and challenges the theoretical frameworks of mainstream American sociology. Most classical and modern theorists assume that their frameworks are universal and can be applied to all societies (Connell 2007). Generally, postcolonial theories critique empire, colonialism, and imperialism and tend to focus on subjugated people and their ways of thinking. Theorists believe that power struggles tied to colonialism shape societies and influence how individuals view the social world (Go 2016).

Smith (2012) argues that there are three primary logics associated with White supremacy in the United States. The first is slavery and anti-Black racism. This is rooted in treating Black people as property. The second pillar is genocide, specifically the genocide of Indigenous people. She argues “this logic holds that Indigenous people must disappear; in fact, they must always be disappearing, in order to enable non-Indigenous peoples’ rightful claim to land” (57). This anchors capitalism. As the last pillar of White supremacy, she identifies Orientalism (see Chapter 6), labeling some people as inferior and a threat to the empire. She argues that this becomes a justification for the United States to be in perpetual war with enemies that are conceptualized as threats.

White Privilege

White privilege, the unearned set of social advantages available to White people, was first identified by Du Bois as a “psychic wage of Whiteness.” As White theorists began to respond to critical theories of race, their scholarship became more reflexive and attentive to the meanings and impacts of White racial identity on people who are White. White theorists have explored this idea, by considering White privilege (McIntosh 1988), White fragility (DiAngelo 2018), and racial identity formation in working-class people who are White (Roediger 2017).

To get at the unspoken privileges associated with Whiteness, McIntosh (1988:31-33) points out some of these taken-for-granted advantages of being White:

“I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.”

“I can be sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.”

“I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race.”

“I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.”

What are some of the other ways White people might be privileged?

Licenses and Attributions for Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

Open Content, Original

“Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“‘Science’ and Social Theory” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Emancipatory Theories” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Critical Race Theory” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Colorblindness/Theory of Racial Ignorance” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Postcolonial Theory” by Jennifer Puentes and Matt Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“White Privilege” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“A Closer Look: Race, Institutions, and Housing” from “Finding a Home: Inequities” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Carla Medel, Katherine Hemlock, and Shonna Dempsey in Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity; all other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Intersection Theory” from “11.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.3. “Franz Boas – posing for figure in USNM exhibit entitled – Hamats’a coming out of secret room – 1895 or before” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 11.4. “Du Bois, W. E. B., Harvard graduation” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 11.6. “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 11.7. “Festival Latinidades 2014” by festival_latinidades is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 11.8. “Kimberlé Crenshaw with Ben Jealous” by Joe Mabel is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

the deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group; the most toxic intergroup relationship.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards and not in comparison to another culture.

a type of prejudice and discrimination used to justify inequalities against individuals by maintaining that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is a set of practices used by a racial dominant group to maximize advantages for itself by disadvantaging racial minority groups.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

freewill or the ability to make independent decisions. As sociologists, we understand that the choices we have available to us are often limited by larger structural constraints.

a theoretical framework that examines how racism is embedded in American social life through its systems and institutions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable or racially occupied.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the net value of money and assets a person has. It is accumulated over time.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

a theory that points to how what we define as race varies and changes in different political, economic, and historical contexts.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

the idea that race is more meaningful on a social level than on a biological level.

also called color-blind racism; a form of racism that is hidden and embedded in our social institutions. The notion that one “does not see color” is problematic and serves to erase the experiences of racial and ethnic minority groups.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience.

a theoretical framework that explores colonial relations and their aftermath. The framework tends to focus on subjugated people.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

an unearned set of social advantages available to White people; the societal privilege that benefits White people, or those perceived to be White, over non-White people in some societies, including the United States.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.