2.1 Chapter Learning Objectives and Overview

Learning Objectives

- Describe how the non-European predecessors of classical sociologists contributed to the foundation of sociology.

- Identify the European theorists and theories that shaped the development of sociology as a discipline.

- Explain how early American sociologists applied theories using empirical research methods.

- Recognize the key concepts and limitations of the three dominant sociological frameworks.

- Examine contemporary theoretical perspectives on society, colonialism, race, gender, and intersectionality.

Overview

During the same period as the American and French Revolutions, a country of enslaved people rose against their colonial enslavers. This revolution, which lasted from 1791 to 1804, resulted in the first country to abolish slavery and in the defeat of one of the most powerful European empires. Yet many people don’t know about the Haitian Revolution, and few mainstream sociologists study this important event. Why is this? Why is the French Revolution given more attention than the Haitian Revolution?

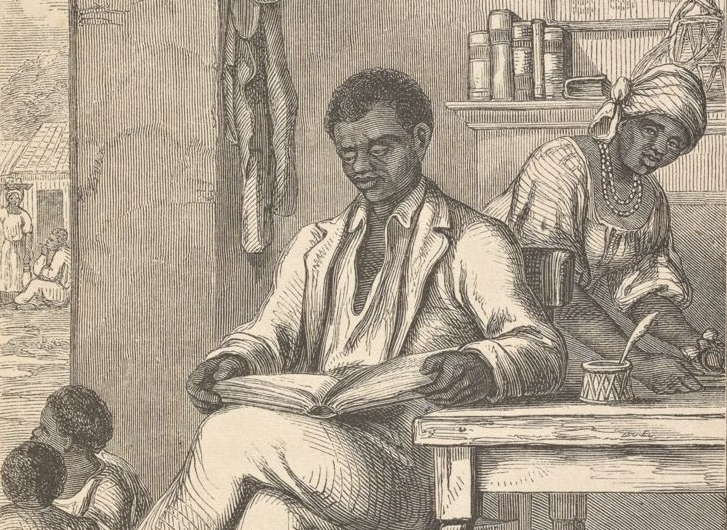

Some argue that by erasing the importance of the Haitian Revolution from modern history, Euro-American countries were able “to claim abolitionist bragging rights rather than reckoning with their centuries-long participation in Atlantic slavery and only slow and grudging decisions to end it” (Gaffield 2020). In other words, Euro-American countries wrote history to make themselves appear as favorable as possible, while downplaying their role in slavery. Yet one theorist we will discuss in this chapter, W. E. B. Du Bois, wrote about the Haitian Revolution and one of its leaders, Toussaint L’Ouverture (figure 2.1).

Du Bois, a sociologist and the first Black American to receive a PhD from Harvard, connected L’Ouverture to several of the founders of sociology and pointed to the Haitian Revolution’s contemporary relevance to the United States. Du Bois noted the Haitian Revolution made Napoleon give up his aims of expanding the French Empire in America. As a result, “All of Montana and the Dakotas, and most of Colorado and Minnesota, all of Washington and Oregon States, came to us as the indirect work of a despised Negro…but today let us not forget our debt to Touissant L’Ouverture” (Du Bois 1996:302).

Using our sociological imaginations, we can also point to how a person’s social position influences what they know or what they deem worthy of theorizing. If influential theorists were largely White and European, how much attention would they give to racial oppression?

In this chapter, we will examine how sociology emerged in Europe and the United States and how social theorists tried to explain the patterns and changes they saw in their societies. In doing so, we will also explore voices that have typically been overlooked in American sociology because of their race, gender, and/or nationality. We will then turn to contemporary approaches to thinking about the social world.

Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Learning Objectives and Overview

Open Content, Original

“Overview” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 2.1. “Toussaint L’Ouverture reading the Abbé Raynal’s work” by J.R. Beard is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.