2.3 Creating a Discipline: European Theorists

As previously noted, the origins of sociology are typically traced back to a variety of European thinkers who lived primarily in the 1800s and early 1900s. Often, these theorists sought to explain the major social changes that were occurring in their societies at the time. Some theorists wrote extensively about very different aspects of society. To help maintain some coherency, we will focus on what the theorists said about the economy and religion when appropriate. Yet, as noted earlier, there were some topics these theorists did not address, such as issues related to gender, race, and colonialism.

Positivism and Social Science: Auguste Comte (France, 1798–1857)

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript. In 1838, the term was reintroduced by Auguste Comte (figure 2.6). Comte was a pupil of social philosopher Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). They both thought that social scientists could study society using the same scientific methods utilized in the natural sciences. Comte developed a theory of positivism, which means that science produces universal laws, science controls what is true, and objective methods allow you to pursue that truth. Comte viewed sociology as the study of two important forces: stability, which he called statics, and change, which he called dynamics. Statics are the laws or structures that contribute to the stability of society. Dynamics are aspects of the society that are changing.

Capitalism and Morals: Harriet Martineau (England, 1802–1876)

Harriet Martineau introduced sociology to English-speaking scholars through her translation of Comte’s writing from French to English (figure 2.7). She was an early analyst of social practices, including economics, social class, religion, government, and women’s rights. Her career began with Illustrations of Political Economy, a work educating ordinary people about the principles of economics (Johnson 2003). She later developed the first systematic methodological international comparisons of social institutions in two of her most famous sociological works: Society in America (1837) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838).

Martineau found the workings of capitalism at odds with the professed moral principles of people in the United States. She pointed out the faults with the free enterprise system in which workers were exploited and impoverished while business owners became wealthy. She further noted that the belief that all are created equal was inconsistent with the lack of women’s rights. Martineau was often discounted in her own time because academic sociology was a male-dominated profession. In the 1970s, feminist scholars rediscovered her work. What would the foundations of sociology look like today if her work had been included earlier on?

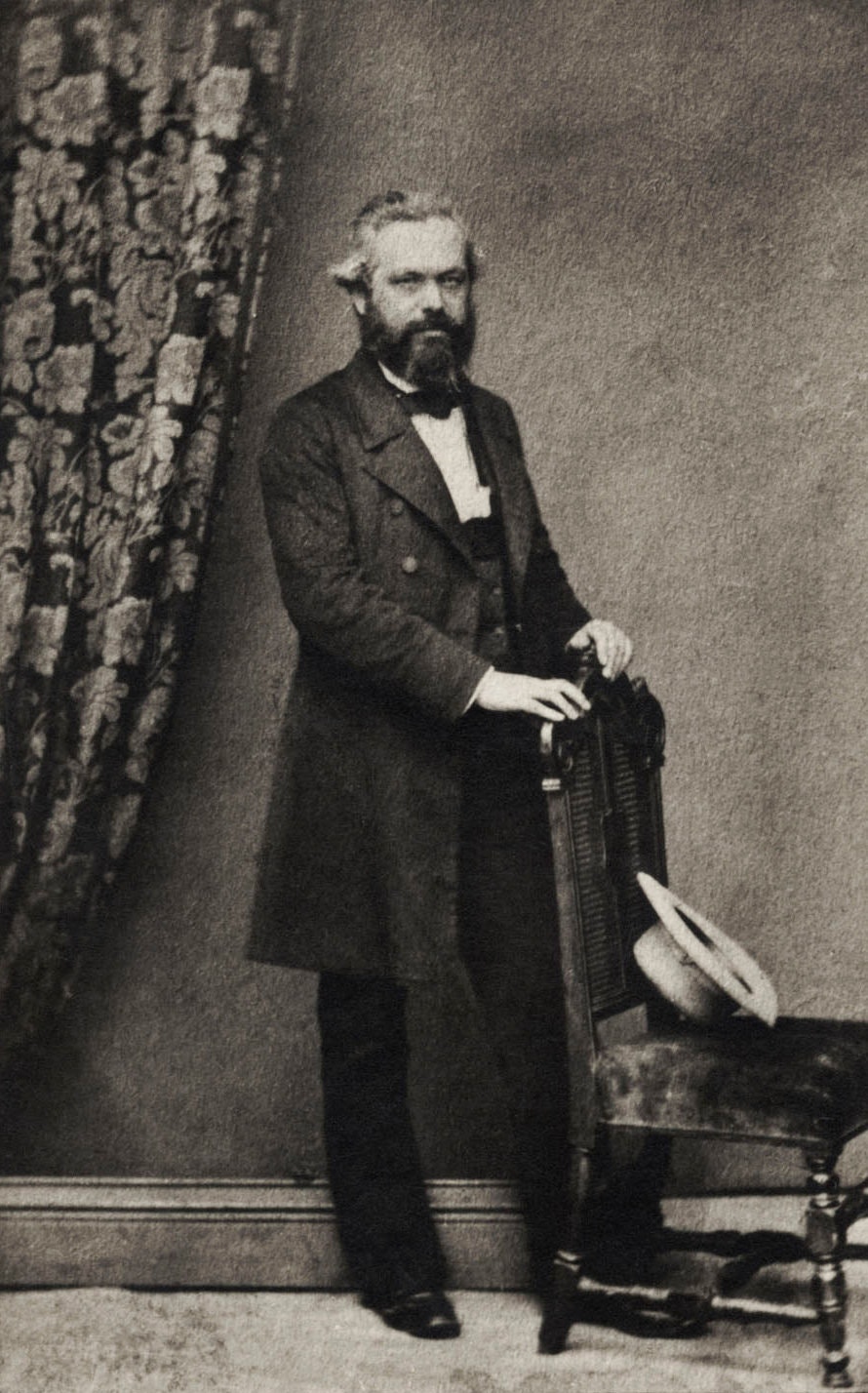

Class and Conflict: Karl Marx (Germany, 1818–1883)

Karl Marx was a social critic and philosopher from Germany (figure 2.8). Exiled from his homeland due to his political beliefs and publications, he ultimately settled in London. He, along with Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), wrote an influential pamphlet called The Communist Manifesto (Marx and Engels 2015 [1848]). In the manifesto, they outline their approach to history and class struggle while arguing for communism. In Capital (1992 [1867]), Marx developed an analysis of how capitalism works. His ideas proved very influential for critical social theories within sociology. To this day, some sociologists continue to draw inspiration from his writings.

Marx argued that history could be divided into a series of distinctive periods, or epochs, based on the social relations and technologies available at the time. The main driver between epochs was class struggle (masters versus slaves, landlords versus serfs, owners versus workers). In each epoch, a revolutionary class would emerge and overthrow those in control, which would instigate the next epoch.

In capitalist societies, Marx identified two distinct social classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie were the wealthy owners/capitalists, who controlled economic production. The proletariat were the workers, who had to sell their labor to live and make a wage. The relationship between the two classes is inherently antagonistic. The bourgeoisie wants to make as much profit as possible while paying the proletariat as little as possible. The proletariat wants to be paid higher wages. Marx argued that the owners exploited the workers by paying them less than what their labor was worth and what the products sold for.

Marx also argued that workers become alienated from their work and that this can happen in four different ways. People can be alienated from the objects they produce, from the process of work itself, from one’s sense of self (“species-being”), and from other workers.

Thinking more broadly about the structures of societies, Marx argued that society could be divided into an economic base and cultural superstructure. The economic base includes economic relations and technology. The cultural superstructure includes all the institutions of a society outside of the economy, including religion, education, family, media, politics, and, more generally, culture. Marx argued the base determines and shapes the superstructure. The superstructure then reinforces what is happening in the base by promoting a specific set of ideas and values. To Marx, whichever class controls the economic base controls the larger superstructure and the dominant ideas of the society. In capitalist societies, that would be the bourgeoisie.

Ultimately, all of this leads to the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. Workers get stuck because there is a reserve army of other workers who are willing to jump in for lower pay if the current workers decide to unionize or challenge the owners. Given the exploitation experienced by the workers, Marx argued they would eventually decide to rise up and overthrow capitalism and the owners. This would result “in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic” (Marx 1998 [1845]). How might we envision other utopias?

Activity: Marx and Mario

Let’s take a moment to consider Marx’s thinking and how it might be applicable to today. Watch the clip in figure 2.9 to further explore Marx’s theory using classic video games.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vz3eOb6Yl1s&ab_channel=Wisecrack

Then answer the following questions:

- How fundamental is work to humans? How might work have changed since Marx’s time?

- Have you ever felt alienated from your work? What was that experience like?

- Marx was in favor of socialism and communism. Why do you think what he predicted did not happen?

Science and Religion: Émile Durkheim (France, 1858–1917)

Émile Durkheim was a crucial voice in the promotion of sociology as a legitimate area of study within France (figure 2.10). In his writing, he argued that sociology was a science, and he provided a set of rules for conducting social scientific research in Rules of the Sociological Method (Durkheim 2014 [1895]; Adams and Sydie 2001). He wrote on a variety of topics, but we will explore his work on the economy, suicide, and religion.

Émile Durkheim was interested in how societies cohere and how people connect. In The Division of Labor in Society (2014 [1893]), he explores how social cohesion changed during the rapid economic and social transition associated with the switch from a feudal economy to an industrial-based economy. Durkheim argued that people in pre-industrial societies related to each other based on common sentiments and moral values. This was possible because of mechanical solidarity. This type of solidarity is based on people feeling similar to each other. In such societies, groups take precedence over the individual. In terms of work, there is not much specialization, and people complete a wide variety of tasks.

In contrast, in organic solidarity, people relate to each other based on specialization and interdependence. Individuality and differences are maximized. He argued that organic solidarity characterized modern industrial societies. With the increased division of labor and specialization of work, we depend more and more on people that we do not know personally.

In 1897, Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research when he published a work titled Suicide (1997 [1897]). Durkheim examined suicide statistics in different police districts to research differences between Catholic and Protestant communities. He attributed the differences in suicide rates to socio-religious forces rather than to individual or psychological causes.

One of his final studies, the Elementary Forms of Religious Life, explores the social underpinnings of religion (Durkheim 2001 [1915]). He defined religion as a unified system of beliefs and practices related to sacred things, or things that are set apart and forbidden. He argued that the common denominator of all religions is their beliefs that divide the world into the sacred and the profane, along with prescriptions for particular ways of behaving toward the sacred.

So what did Durkheim mean by the sacred and the profane? The sacred involves feelings of awe, fear, and reverence. Animals, places, plants, or people can be designated as sacred. It is something added to the object or thing by the group. The profane is the opposite of the sacred. It is routine daily life, such as work and household chores. Durkheim saw the profane as weakening social bonds and shared commitments to beliefs.

How does society sustain itself in the face of the profane? Durkheim argued that rituals play a significant role in helping people reaffirm their worship of shared objects, have shared experiences, and sustain emotional bonds. Rituals are when society comes together to worship the sacred and reaffirm people’s connections with one another. Rituals such as music, chants, and dance create a collective emotional excitement called collective effervescence. This provides a strong sense of group belonging, with people losing their sense of self in the collective experience. This collective energy sustains people in the face of the profane.

Overall, this led Durkheim to view the existence of religion as resulting from the need of societies to reconstruct their social bonds and counteract the feelings of disconnection caused by daily routines. The other conclusion Durkheim reached about religion was that it was nothing less than the worship of society itself.

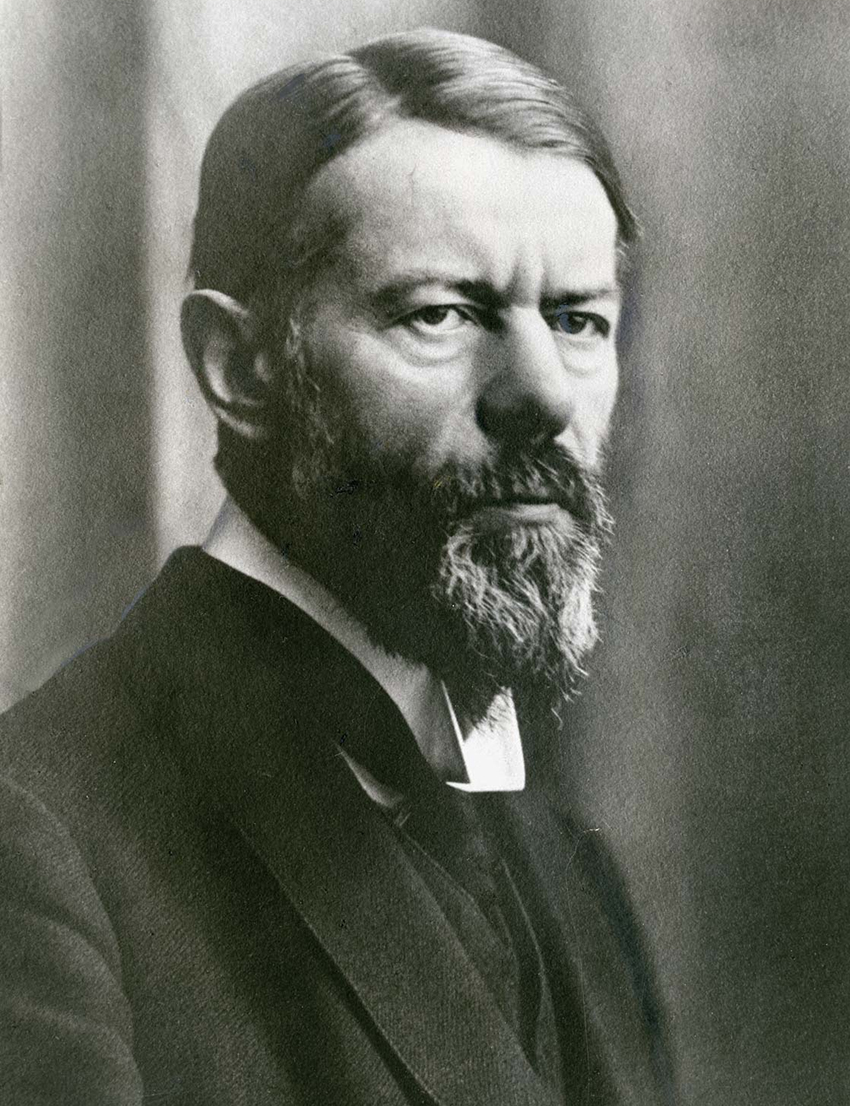

The Protestant Ethic and Rationality: Max Weber (Germany, 1864–1920)

Max Weber was a well-known German intellectual whose work spanned multiple disciplines (figure 2.11). A prolific scholar, he was also politically active in pre-World War I Germany. Within sociology, his writings on the development of capitalism, the economy, social action, and research methods continue to be influential. Weber was interested in how capitalism emerged and where it was going. Unlike Marx, who based his theories on class struggle and economic relations, Weber focused on the role that ideas played in the spread of capitalism.

Weber began by observing that Protestants were overrepresented in capitalist economic activity and asking why. He argued in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (2002 [1904–1905]) that Protestants had a “Protestant ethic” that involved the systematic pursuit of salvation in the everyday world.

According to German priest and religious reformer Martin Luther, to live in a way acceptable to God was to live in the world and fulfill one’s duties. This contrasted with the idea that the most virtuous existence was a monastic one in which people renounce worldly obligations and wealth. Luther preached that the best way to serve God was to pursue one’s vocation, which became known as a “calling.” This meant each person had a specific place and job in God’s scheme. Hard work in one’s calling would bring about material rewards to the believer. These rewards would provide psychological reassurance that one was headed toward heaven because Protestants assumed that God would not reward those who were damned. Thus, the wealth people accumulated while working hard in their calling became acceptable.

The Protestant ethic resulted in people who worked hard but didn’t spend or enjoy their profits. This pattern of behavior aligned with what Weber called the “spirit of capitalism,” or the overall guiding principles of capitalism. One of these principles is acquisition, which the Protestant ethic encouraged through hard work and as evidence of salvation. Another principle is reinvestment, which entails a commitment to continuously use profits to increase capital instead of using the profits for consumption, something religious doctrine frowned upon. The beliefs associated with the Protestant ethic helped capitalism emerge and make it morally acceptable.

By the twentieth century, capitalism no longer needed the direct support of religious beliefs. Once it came into power, secular capitalism had a self-sustaining, treadmill-like character. What was left was instrumental rationality, a way of thinking that focused on short-term goals and acting in a self-interested manner. To some extent, people with this way of thinking approach social life by asking “What is in it for me?” With the increase in instrumental rationality and the declining influence of moral beliefs and values over capitalism, Weber saw capitalism heading toward an “iron cage” of disenchantment. There is a loss of values and meaning, coupled with a rise in cold calculations and efficiency.

Weber also believed that it was difficult, if not impossible, to use standard scientific methods to accurately predict the behavior of groups as some sociologists hoped to do. He argued that the influence of culture on human behavior had to be taken into account. This even applied to researchers, who should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and German academic Wilhelm Dilthey introduced the concept of verstehen, a German word that means to understand in a deep way. In seeking verstehen, outside observers of a social world—an entire culture or a small group—attempt to understand it from an insider’s point of view.

Licenses and Attributions for Creating a Discipline: European Theorists

Open Content, Original

“Creating a Discipline: European Theorists” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Marx and Mario” by Matthew Gougherty is adapted from What is Marxism? (Karl Marx + Super Mario Bros) by Wisecrack, shared under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include authoring questions and framing the activity.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Positivism and Social Science ” is modified from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Added detail about positivism, statics and dynamics.

“Capitalism and Morals” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Added last two sentences on rediscovery of her work.

Paragraph on Durkheim’s study of suicide in “Science and Religion” is modified from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency.

Paragraph on verstehen in “The Protestant Ethic and Rationality” is modified from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency.

Figure 2.6. “Top Auguste Comte place Sorbonne Paris” is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 2.7. “Portrait of Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.8. “Karl Marx, May 1861” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.10. “Emile Durkheim” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.11. “Max Weber, 1918” is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.9. “What is Marxism? (Karl Marx + Super Mario Bros)” by Wisecrack is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

Comte’s theory which suggests that science produces universal laws, science controls what is true, and objective methods allow you to pursue that truth.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

in Marx’s theory, the workers that must sell their labor.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

the net value of money and assets a person has. It is accumulated over time.