3.6 Qualitative Research Methods Part 1

In the next two sections, we will cover a variety of qualitative research methods. This section will focus on many different forms of ethnographic research, or ethnography. We will explore interviewing and content analysis in the next section.

Ethnography

Another research method sociologists use to collect data is ethnography—studying people in their environments to understand the meanings they give to their activities. The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet people where they live, work, and play. Ethnography, or ethnographic research, involves gathering primary data from a natural environment. This field research, or fieldwork, requires the sociologist to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds.

In fieldwork, sociologists are the ones out of their element. The researcher interacts with or observes people and gathers data along the way. While field research often begins in a specific setting, the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Ethnographers aim to provide a “thick description” of the setting and interactions they observe (Geertz 1973). For example, rather than writing “Parker smiled,” the researcher would elaborate on what is observable and may write something like “They parted their lips with an upward lift at the ends of their mouth, displaying a few top teeth.” The aim of the “thick description” approach is for researchers to account for both what they see and the context in which they view it as a way to deeply understand society. This level of detail can make the reader feel as though they are experiencing the setting firsthand.

Ethnographic research is conducted through participant observation. Generally, the goal is to study groups of people and understand what is meaningful to group members, but there are other types of ethnography that we will learn about in the next sections. Some center on the experience of the researcher (autoethnography), while other approaches analyze gendered relations in power structures (institutional ethnography).

Participant Observation

Participant observation refers to a style of ethnographic research in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. For instance, at the beginning of a field study, a researcher might have a question like “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be houseless?” The researcher might then work as a server in a diner, experience houselessness for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside. The ethnographer will be alert and open-minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, and the researcher will be able to either make connections to existing theories or develop new theories based on their observations. This approach will guide the researcher in analyzing data and generating results.

How do researchers decide what roles to maintain in their field site? Several factors influence this. The conditions of the setting may limit or enable the researcher’s level of participation. The personal characteristics of the researcher, including abilities, theoretical orientations, and demographic characteristics, may influence the researcher’s membership in the setting. Finally, a researcher’s role may change over time due to changes in either the researcher or the setting during data collection (Adler and Adler 1987).

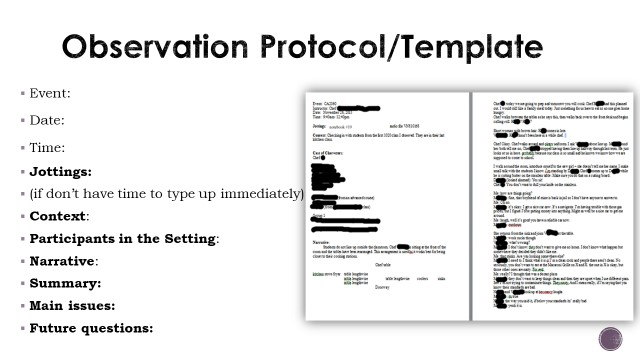

Researchers gain insights into cultural practices over time and through repeated analysis of many aspects of field sites. To facilitate this process, ethnographers must learn how to take useful and reliable notes regarding the details of life in their research contexts. These fieldnotes are a major part of the data researchers will analyze and connect to sociological theories. As you can see in figure 3.5, fieldnotes are often taken with brief handwritten notes’ while a researcher is observing participants in the field. Figure 3.6 shows an example of an observation protocol or template that the authors of your text find helpful in their own research. Consistently documenting your observations helps with data. Many researchers use qualitative data management software to help them organize the documents they analyze which later conclusions will be based.

Autoethnography

Autoethnography is a form of participant observation in which the researchers use self-reflection and writing to examine their experiences in a setting. They connect their autobiographical story to wider cultural, political, and social meanings and understandings (Ellis 2004; Marechal 2010). Autoethnographic methods include journaling, interviewing one’s self, and generating cultural understanding through reflective writing.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focus on gendered relationships within institutions. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith (1990), institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male-dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work is seen to challenge sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from the male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography (Fensternmaker n.d.).

International Research

International research is conducted outside of the researcher’s immediate geography and society. This work carries additional challenges considering that researchers often work in regions and cultures different from their own. Researchers need to make special considerations to counter their own biases, navigate linguistic challenges, and ensure the best cross-cultural understanding possible. For an optional deeper dive, look at this map and descriptions of field projects around the world [Website] by students at Oxford University’s Masters in Development Studies. What are some interesting projects that stand out to you?

For example, in 2021, Jörg Friedrichs at Oxford published his research on Muslim hate crimes in areas of North England where Islam is the majority religion. He studied police data on racial and religious hate crimes in two districts to look for patterns related to the crimes. He related those patterns to the wider context of community relations between Muslims and other groups and presented his research to practitioners in police, local government, and civil society (Friedrichs 2021).

A Closer Look: Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods

An emerging fieldwork methodology involves the production of Indigenous knowledge by Indigenous communities themselves. Indigenous communities are distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties to the natural resources and lands where they live, occupy, or from which they have been displaced. As the world becomes increasingly aware of the environmental crisis, researchers are more often acknowledging the ways that Indigenous peoples care for their ecological surroundings. For example, communities and fire agencies in Northern California and the Northwest are looking to Indigenous fire management practices to help control wildfires (Kuhn 2021). As Indigenous communities conduct their own fieldwork to identify and document their knowledge, they can engage with research as agents of ecological conservation.

Alongside better recognition of Indigenous knowledge is a recent emphasis on research method insights led by Indigenous leaders and scholars. This body of methods emerges as a response to the colonialist roots of international fieldwork and the damage that has been caused by some researcher-community relationships. The roots of international fieldwork are tied to the regime of settler colonialism and the colonialist thinking that came with it. Until recently, international fieldwork was viewed as the study of the “exotic” other.

Many argue that contemporary international fieldwork needs to be decolonized (Kim 2019, Datta 2018). Decolonization refers to the active resistance against colonial powers. It involves a shifting of power toward political, economic, educational, cultural, and psychic independence that originates from a colonized nation’s own Indigenous culture. This context reflects the need for diverse voices and perspectives, and carries with it an expectation that researchers engage in some level of reflexivity in their studies. In other words, researchers should acknowledge their own reactions and motives in the field.

An early promoter of these ideas is Linda Tuhiwai Smith (of the Māori iwi [tribes] Ngati Awa and Ngati Porou) in New Zealand. In her 1999 book, Decolonizing Methodologies, Tuhiwai Smith encourages scholars to “research back,” or critically and creatively interrogate the role that one’s self, discipline, and community has played in engaging with communities of study in a way that can shift our knowledge in the present. Researching back disrupts colonizing practices and attempts to move toward respectful, ethical, and useful practices (Tuhiwai Smith 1999).

We can explore this concept more in the following five-minute video [Streaming Video] (figure 3.7) during which Dr. Shawn Wilson and Dr. Monica Mulrennan at Concordia University in Montréal, Québec, explore decolonized methodologies in research.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqYiCrZKm0M

Considering the ideas in the video, take a moment to reflect on these questions:

- The film mentioned that Indigenous research methods can provide an opportunity for the renewal of relationships between those working within systems of research and Indigenous communities. How do you see this renewal happening?

- What does the quote by the Indigenous geographer, mentioned in the film, mean to you? “…if we assume we’re guests we will be welcome, but if we assume we’ll be welcome we’re no longer guests.”

Licenses and Attributions for Qualitative Research Methods Part 1

Open Content, Original

“Qualitative Research Methods Part 1” by Jennifer Puentes, Matthew Gougherty, and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“International Research” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“A Closer Look: Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.6. Photo by Jennifer Puentes licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The first three sentences of paragraph two in “Ethnography” are from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and brevity by Jennifer Puentes.

The last four sentences of paragraph one and paragraph two of “Participant Observation” are from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Institutional Ethnography” is adapted from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for clarity and brevity.

Figure 3.5. Photo by Kari Shea is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Decolonization” definition from Racial Equity Tools is included under fair use.

“Indigenous communities” definition from World Bank is included under fair use.

Figure 3.7. “Decolonizing Methodologies: Can relational research be a basis for renewed relationships?” by Concordia University is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

research methods that work with non-numerical data and attempt to understand the experiences of individuals and groups from their own perspectives. With qualitative approaches, researchers examine how groups participate in their own meaning making and development of culture.

the study of people in their environments to understand the meanings they give to their activities.

a systematic approach to record and value information gleaned from secondary data as it relates to the study at hand.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

the ability of the researcher to examine how their own social position influences how and what they research. Reflexivity requires the researcher to evaluate how their own feelings, reactions and motives influence how they think and behave in a situation.