3.9 Ethics

Sociologists conduct studies to shed light on human behaviors. Knowledge is a powerful tool that can be used to achieve positive change. As a result, conducting a sociological study comes with a tremendous amount of responsibility. Like all researchers, sociologists must consider their ethical obligation to avoid harming human subjects or groups while conducting research.

Research studies that use human subjects often undergo review by a community at the researcher’s university called the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If projects are approved, researchers seek out participants. Research participants are thanked for their participation and sometimes offered a chance to see the results of the study.

German sociologist Max Weber identified another crucial ethical concern. Weber understood that personal values could distort the framework for disclosing study results. While he accepted that some aspects of research design might be influenced by personal values, he declared it was entirely inappropriate to allow personal values to shape the interpretation of the responses. Sociologists, he stated, must establish value neutrality, a practice of remaining impartial, without bias or judgment, during the course of a study and in publishing results (Weber 1949). Sociologists are obligated to disclose research findings without omitting or distorting significant data.

Is value neutrality possible? Many sociologists believe it is impossible to retain complete objectivity. They caution readers, rather, to understand that sociological studies may contain a certain amount of value bias. This does not discredit the results but allows readers to view them as one form of truth—one fact-based perspective. Investigators are ethically obligated to report results, even when they contradict personal views, predicted outcomes, or widely accepted beliefs.

ASA Code of Ethics

The American Sociological Association, or ASA, is the major professional organization of sociologists in North America. The ASA is a great resource for students of sociology as well. The ASA maintains a code of ethics—formal guidelines for conducting sociological research—consisting of principles and ethical standards to be used in the discipline. These formal guidelines were established by practitioners in 1905 at John Hopkins University and revised in 2018. You can read the full code of ethics [Website], if you wish. When working with human subjects, these codes of ethics require researchers to do the following:

- Professional Competence: Sociologists should maintain a high level of competence and recognize the limitations of their expertise. Sociologists should participate in ongoing education to remain professionally competent and consult with other professionals when necessary.

- Integrity: Sociologists should be honest, fair, and respectful to others. Sociologists do not intentionally engage in practices that harm the welfare of themselves or others.

- Professional and Scientific Responsibility: Sociologists maintain high scientific and professional standards. They accept responsibility for their work and show respect for other sociologists when they disagree on theoretical and methodological approaches.

- Social Responsibility: Sociologists respect people’s rights, dignity, and diversity. They are aware of cultural, individual, and role differences in serving, teaching, and studying groups of people with different characteristics.

- Human Rights: Sociologists are committed to promoting the human rights of all people through their research, teaching, practice, and service.

Unethical Studies

Unfortunately, when these codes of ethics are ignored, it creates an unethical environment for humans involved in research studies. Throughout history, there have been numerous unethical studies, some of which are summarized next. Unethical research in the past led to the development of the Belmont Report, a document that outlines ethical principles and guidelines for human subject research. You have the option to read the full report [Website]. Three core principles are identified: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. As you learned in the last section, the Belmont Report influences the code of ethics followed by sociologists today.

The Tuskegee Experiment

This study was conducted in 1932 in Macon County, Alabama, and included 600 African-American men, including 399 diagnosed with syphilis (figure 3.9). The participants were told they were diagnosed with a disease of “bad blood.” Penicillin was distributed in the 1940s as the cure for the disease, but unfortunately, the African-American men were not given the treatment because the objective of the study was to see “how untreated syphilis would affect the African-American male” (Caplan 2007).

Henrietta Lacks

Ironically, this study was conducted at the hospital associated with Johns Hopkins University, where the ASA code of ethics originated. In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was receiving treatment for cervical cancer at John Hopkins Hospital when doctors discovered that she had “immortal” cells that reproduce rapidly and indefinitely, making them extremely valuable for medical research (figure 3.10). Without her consent, doctors collected and shared her cells to produce extensive cell lines. Lacks’s cells were widely used for experiments and treatments, including the polio vaccine, and were put into mass production. Today, these cells are known worldwide as HeLa cells (Shah 2010).

Milgram Experiment

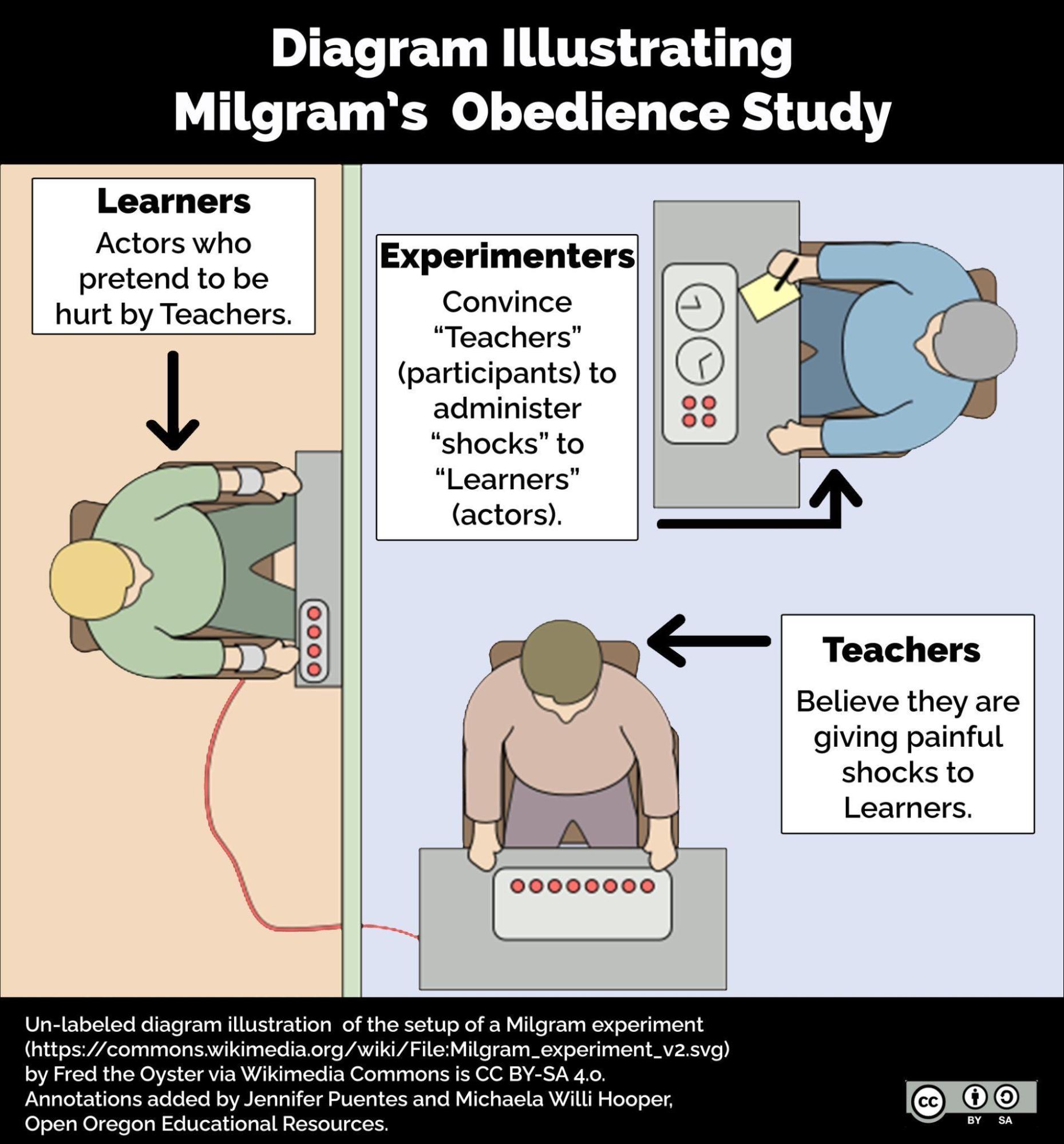

In 1961, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment at Yale University. Its purpose was to measure the willingness of study subjects to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their conscience. Figure 3.11 is a diagram of his study. Participants who were assigned the role of “teacher” believed they were administering electric shocks to “learners” who gave incorrect answers to word-pair questions. No matter how concerned they were about administering the increasingly intense shocks, the teachers were told to keep going. Very few of the teachers refused to participate. The extreme emotional distress faced by the teachers, who believed they were hurting other people, is a major ethical concern (Vogel 2014). Subjects who were teachers were debriefed after the experiment and met the learner they were paired with.

Laud Humphreys

In the 1960s, Laud Humphreys conducted an experiment at a restroom in a park known for same-sex sexual encounters. His objective was to understand the diversity of backgrounds and motivations of people seeking same-sex relationships. His ethics were questioned because he misrepresented his identity and intent while observing and questioning the men he interviewed (Nardi 1995).

Ethics in International Research

Research in international settings follows the same ethical guidelines as research in the sociologist’s home environment. However, researchers must also consider the cross-cultural nature of the work and navigate the unequal power imbalances that exist between researchers and the communities they are studying.

In international settings, there may exist different cultural approaches and understandings about ethics in research in general, so it is helpful for researchers to establish relationships with local organizations to better understand those cultural differences. Members of local organizations can advise on any cultural, moral, and political sensitivities that might influence risks to the safety and dignity of participants.

Researchers are encouraged to pay close attention to power imbalances between themselves and local communities. This is especially true in low-income countries or countries that are in conflict or facing political instability. These power imbalances may be real or perceived and may impact the degree to which community members feel their participation is voluntary, how freely they grant specific consent for participation, and what they expect the research will contribute, if anything, to their community. Special attention needs to be provided to bridge cultural and language gaps to make certain that participants understand the details of the informed consent, which may require providing translated or orally-presented information (International Research n.d).

Activity: A Closer Look at Research Ethics

Let’s look at how one organization outlines ethics for international research. The Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) works to strengthen organizations’ impact on poverty, so their focus on international research has a humanitarian or development lens (figure 3.12).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ylkKCgEIMws

Please answer the following question:

- How do ACFID’s principles for ethical research compare to the principles we covered in this section?

Licenses and Attributions for Ethics

Open Content, Original

“Ethics” paragraph two is by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ethics in International Research” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: A Closer Look at Research Ethics” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.11. “Diagram Illustrating Milgram’s Obedience Study” is adapted from Milgram experiment v2 by Fred the Oyster, and is licensed CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications: Annotations added by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Ethics” is modified from “2.3 Ethical Concerns” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency, brevity, and to update information.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.9. “Photograph of Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study” from the Courtesy of the National Archives at Atlanta is included under fair use.

Figure 3.10. Photo by Lacks Family from History.com is included under fair use.

Figure 3.12. “Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development” by ACFID is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

formal guidelines for conducting sociological research, consisting of principles and ethical standards to be used in the discipline.

the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among individuals.

the testing of a hypothesis under controlled conditions.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.