4.5 Socialization

Socialization is the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values. Socialization is critical both to individuals and to the societies in which they live. It illustrates how completely intertwined human beings and their social worlds are. It is through teaching culture to new members that a society perpetuates itself. If new generations of a society don’t learn its way of life, it ceases to exist. Whatever is distinctive about a culture must be transmitted to those who join it for a society to survive.

For example, for U.S. culture to continue, children in the United States must learn about cultural values related to democracy: they have to learn the norms of voting, as well as how to use material objects such as voting machines. They may learn these through watching their parents or guardians vote, or, in some schools, by using real machines in student government elections. Of course, some would argue that it’s just as important in U.S. culture for the younger generation to learn the etiquette of eating in a restaurant or the rituals of tailgate parties at football games. There are many ideas and objects that people in the United States teach children about in hopes of keeping the society’s way of life going through another generation.

Recent Developments in the Study of Socialization

Some experts assert that who we are is a result of nurture—the relationships and caring that surround us. Others argue that who we are is based entirely on genetics. According to this belief, our temperaments, interests, and talents are set before birth. From this perspective, then, who we are depends on nature. Though genetics and hormones play an important role in human behavior, sociology’s larger concern is the effect society has on human behavior, or the nurture side of the nature versus nurture debate.

In sociology, socialization has typically been associated with the structural functionalist theoretical tradition. From this perspective, people internalize or download the values and culture of which they are a part. We, in effect, download culture from our parents and caregivers much like our phones download and install updates. Structural functionalists argue this happens at a young age. Socialization then provides stability and continuity for a society. However, this understanding of socialization tends to downplay agency, one’s ability to choose, and the influence of power relationships (Guhin, Calarco, and Miller-Idriss 2021).

Contemporary sociological perspectives on socialization draw from symbolic interactionism and social constructionism. These perspectives emphasize that people are active within their socialization. As an example, Corsaro (2003) shows that children develop their own peer cultures, which helps children reinterpret the adult culture that surrounds them.

Agents of Socialization

When discussing socialization, it is useful to distinguish between the agents of socialization and the target of socialization. The agents of socialization are the ones doing the socializing and incorporating the new person into the particular culture and group. The targets of socialization are the people being socialized.

Among the agents of socialization, you can distinguish between social group agents and institutional agents. Social groups often provide the first experiences of socialization. Families, and later peer groups, communicate expectations and reinforce norms. People first learn to use the tangible objects of material culture in these settings and are introduced to the beliefs and values of society.

Family is the first agent of socialization. Mothers and fathers, siblings, and grandparents, plus members of an extended family, all teach children what they need to know. For example, they show children how to use objects (such as clothes, computers, eating utensils, books, and bikes); how to relate to others (some as “family,” others as “friends,” still others as “strangers” or “teachers” or “neighbors”); and how the world works (what is “real” and what is “imagined”). As you are aware, either from your own experience as a child or from your role in helping to raise one, socialization includes teaching and learning about an unending array of objects and ideas.

Keep in mind, however, that families do not socialize children in a vacuum. Many social factors affect the way a family raises its children. For example, we can use sociological imagination to recognize that individual behaviors are affected by the historical period in which they take place. Sixty years ago, it would not have been considered especially strict for a father to hit his son with a wooden spoon or a belt if he misbehaved, but today that same action might be considered child abuse.

A peer group is made up of people who are similar in age and social status and who share interests. Peer group socialization begins in the earliest years, such as when kids on a playground teach younger children the norms about taking turns, the rules of a game, or how to shoot a basket. As children grow into teenagers, this process continues. Peer groups become important to adolescents in a new way as they begin to develop an identity separate from their parents and exert independence. Additionally, peer groups provide opportunities for socialization since kids usually engage in different types of activities with their peers than they do with their families. Peer groups provide adolescents’ first major socialization experience outside the realm of their families. Interestingly, studies have shown that although friendships rank high in adolescents’ priorities, this is balanced by parental influence.

The social institutions of our culture also inform our socialization. Formal institutions like schools, workplaces, and the government teach people how to behave in and navigate these systems. Other institutions, such as the media, contribute to socialization by inundating us with messages about norms and expectations.

Most U.S. children spend about seven hours a day, 180 days a year in school, which makes it hard to deny the importance school has on their socialization (U.S. Department of Education 2004). Students are not in school only to study math, reading, science, and other subjects—the intended function of this system. Schools also serve an unintended, and often unrecognized, function in society by socializing children into behaviors like practicing teamwork, following a schedule, and using textbooks.

Just as children spend much of their day at school, many U.S. adults at some point invest a significant amount of time at a place of employment. Although socialized into their culture since birth, workers require new socialization in a workplace in terms of both material culture, such as how to operate the copy machine, and nonmaterial culture, such as whether it’s okay to speak directly to the boss.

While some religions are informal institutions, here we focus on practices followed by formal institutions. Religion is an important avenue of socialization for many people. The United States is full of synagogues, temples, churches, mosques, and similar religious communities where people gather to worship and learn. Like other institutions, these places teach participants how to interact with the objects that constitute the religion’s material culture, such as a mezuzah, a prayer rug, or a communion wafer. For some people, important ceremonies related to family structure, such as marriage and birth, are connected to religious celebrations. Many religious institutions also uphold gender norms and contribute to their enforcement through socialization. From ceremonial rites of passage that reinforce the family unit to power dynamics that reinforce gender roles, organized religion fosters a shared set of socialized values that are passed on through society.

Socialization as a Life-Long Process

Although we do not think about it, many of the rites of passage people go through today are based on age norms established by the government. To be defined as an “adult” usually means being eighteen years old, the age at which people become legally responsible for themselves. Similarly, 65 years old is the start of “old age” since most people become eligible for senior benefits at that point.

Each time we embark on one of these new categories—senior, adult, taxpayer—we must be socialized into our new role. Seniors must learn the ropes of Medicare, Social Security benefits, and senior shopping discounts. When U.S. males turn 18, they must register with the Selective Service System within 30 days to be entered into a database for possible military service. These government dictates mark the points at which we require socialization into a new category.

In the process of socialization, adulthood brings a new set of challenges and expectations, as well as new roles to fill. As the aging process moves forward, social roles continue to evolve. The pleasures of youth, such as wild nights out and serial dating, become less acceptable in the eyes of society. Responsibility and commitment are emphasized as pillars of adulthood, and adults are expected to “settle down.” During this period, many people enter into a marriage or civil union, bring children into their families, and focus on a career path. They become partners or parents instead of students or significant others.

Just as young children pretend to be doctors or lawyers, play house, and dress up, adults also engage in anticipatory socialization, the preparation for future life roles. Examples include a couple who cohabitate before marriage or soon-to-be parents who read infant care books and prepare their home for the new arrival. As part of anticipatory socialization, adults who are financially able begin planning for their retirement, saving money, and looking into future healthcare options. The transition into any new life role, despite the social structure that supports it, can be difficult.

In the process of resocialization, old behaviors that were helpful in a previous role are removed because they are no longer of use. Resocialization is necessary when a person moves to a senior care center, goes to boarding school, or serves a sentence in the prison system. In the new environment, the old rules no longer apply. The process of resocialization is typically more stressful than normal socialization because people have to unlearn behaviors that have become customary to them. While resocialization has a specific meaning, many organizations consider their training or retraining processes to embody elements of resocialization.

A Closer Look: The Impact of Socialization on Domestic Violence

People often ask, “Why did they stay with their abuser?” or “What did they do to be treated that way?” as if the victim somehow deserved violence, but rarely do we hear people ask, “Why did they abuse?” Intimate partner violence and domestic violence are rooted in conflicts between individuals and more broadly in a society that is rife with power imbalances and structures that serve to maintain and reinforce these differences. As children, we grow up in families that convey implicit messages that originate in familial traditions, religious beliefs, culture, and society. These messages are continually reinforced and built upon as we are exposed to more agents of socialization such as the media, peers, colleagues, and the educational system.

Often, discussions of domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV) are avoided or met with discomfort. Sometimes these discussions are discounted as we hear “not all men,” “not me,” or “not anyone I know.” But statistics suggest something different. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, nearly 20 people per minute experience physical abuse by an intimate partner, and one in four women and one in nine men have or will experience severe intimate partner violence (“National Statistics”). Yet we continue to engage in violence, as participants, victims, or bystanders.

Take this quote from a 32-year-old domestic violence survivor attending a domestic violence support class in Oregon:

He was so sweet, supportive and really there for me, ya know….everybody else took from me and bailed, brought me flowers and coffee to me at work, showed up wherever I was, just to be there…but it all changed and no one believe me, because he was just so nice, so loving, so concerned out in front of everyone, but with just me, oh no, totally different, like Jekyll and Hyde.

Why didn’t anyone notice or believe? Is it because the abusers put on a charming facade, but hide their true selves so that no one knows much about them? Or is it because we believe it is normal in our society for those in power to act as they wish, a social norm engrained from childhood?

Consider what the following messages might convey to young children: “What a big boy!” “You are daddy’s little man.” “Boys don’t cry, they buck up!”

How many of us have heard or said this to our little brothers, nephews, sons, or the neighbor’s son? Alternatively, how many of us have reinforced gender stereotypes for women by giving pink, princess-themed gifts? How many have heard or said to little girls, “You are so beautiful,” “What a pretty dress,” “Be careful, you’ll get dirty,” or “Be nice, he is being that way because he likes you”?

These ideas are reflected in the top-selling toys Lego and Barbie. Legos, aimed predominantly at boys, reinforce adventure and creativity, while Barbies, aimed predominantly at girls, reinforce ideals of beauty and nurturing. These toys and messages are socializing young individuals to value being pretty, kind, and forgiving as females or being rough, strong, and independent as males.

Reflecting on the direct or implied messages to boys to “not cry” and girls to “be pretty and careful,” we see that both model repression of certain emotions based on gender and over-expression of other emotions or actions. Socialization reinforces the power imbalance between genders with greater ramifications for those at risk of or in domestic violence scenarios. One 22-year-old domestic violence survivor attending a domestic violence support class in Oregon reflected on her childhood socialization and how it was gendered:

I couldn’t argue or question anything when I was little. I would get in so much trouble…was just supposed to be seen and not heard but my brother could say or ask whatever he wanted and he was ‘so great’ because he was critically thinking. Today, I don’t know how to stand up for myself in my relationships and I just keep getting smacked around because I just take it, ’cause that’s what I was told to do.

These socializing messages are not just confined to young children with toys and cartoons. Popular shows marketed to adults are contributing to the continued socialization and reinforcement of violence. A prime example is the popular Netflix show You, which showcases an obsessive individual who engages in stalking and violence. The portrayal of a handsome father who experienced childhood trauma and is now a serial stalker and killer can and has led viewers to empathize with and justify his behaviors. This helps perpetuate the problems of violence against women and domestic violence overall. From the following quotes you can see how a show like You gives a distorted view of reality:

“I love that show [You]! Even though I know it’s just a prettier version of my life…well, minus the killing and add some beat-downs, but all the other shit.” ~46-year-old domestic violence survivor attending domestic violence support classes in Linn County, Oregon

“I watched that You show because my clients were talking about it and my kid liked it. It makes it hot to be obsessed over or have people show up on your doorstep, distorts or glamorizes the reality of it.” ~LCSW, Linn County, Oregon

These cultural messages can be layered on the messages from our families of origin, as girls and women are taught to preserve the family at any cost. The woman, allocated the role of being responsible for raising children and maintaining the family, is often given cues that it is better for the family—for the children—to accept this abuse. These learned behaviors of dominance and acceptance are then passed on to the children.

One way to highlight that power dynamic is to look at what men do while women are performing unpaid childcare and housework. Recent research has found that men spend between 47 percent and 35 percent of their time in leisure activities, while mothers are engaging in childcare and household labor. This points to a dramatic difference in who has power within the home, where one person is doing what they want while the other partner is still essentially working (Kamp Dush, Yavorsky, & Schoppe-Sullivan 2018). While who gets to relax and who does the unpaid household labor does not seem on par with who is experiencing abuse, the power dynamic of who has the power to “do as they wish” as opposed to doing what is expected of them reinforces socialized messages of dominance and oppression, of belief and dismissal, of power and authority, and of powerlessness and dependence. These imbalances typically fall along the lines of gender. In an interview, one domestic survivor reflected on the experience:

“There was a lot of gaslighting and minimizing of my experience, which feels rooted in the norms of society and the version of history that gets believed. The hardest part was that in our broader community, I felt like I wasn’t believed as a woman. It was really astounding—despite everything that was happening in the world with awareness about violence against women, Me Too, etc.—that the response from so many people was to believe my male partner and not me. And he totally took advantage of that and refused to see how he exploited his privilege.”

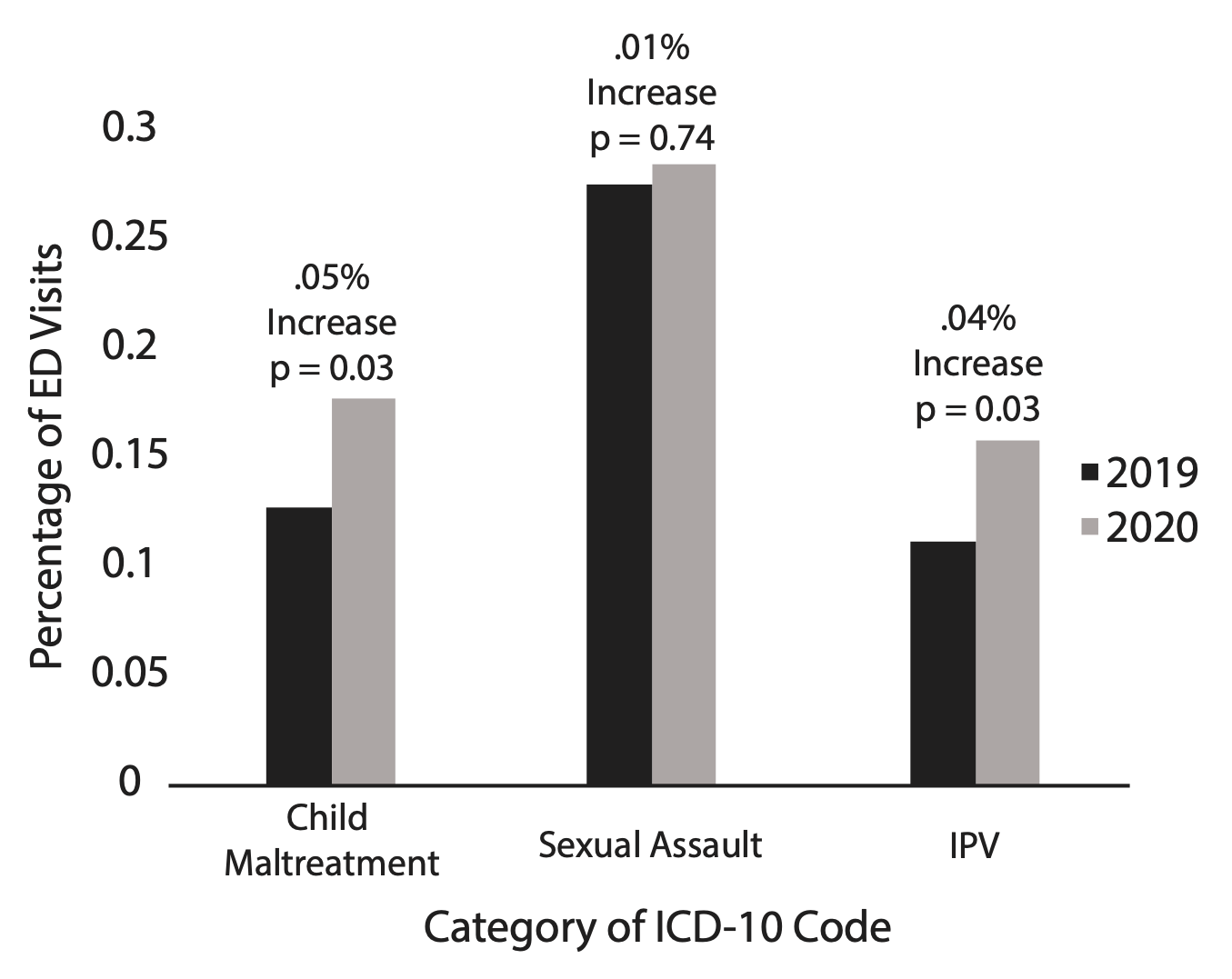

Consider the following data, which reports how IPV/DV increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 4.11).

Overall, our responsibility is to recognize how we are socialized to view the power dynamics of gender and how we can begin to alter our interactions that influence others.

Licenses and Attributions for Socialization

Open Content, Original

“Socialization” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“A Closer Look: The Impact of Socialization on Domestic Violence” by Sonya James is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Socialization” definition from “Ch. 5 Key Terms” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Socialization” introductory paragraphs and first paragraph from “Recent Developments in the Study of Socialization” remixed from “5.2 Why Socialization Matters” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity.

“Agents of Socialization” paragraphs on different agents and “Socialization as a Life Long Process” first two paragraphs modified from “5.3 Agents of Socialization’’ by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity.

“Socialization as a Lifelong Process” third, fourth, and fifth paragraphs modified from “5.4 Socialization Across the Life Course” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity.

Figure 4.11. “Percentage of emergency department visits with ICD-10* codes related to child maltreatment, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence” by Pallansch et al. 2022 is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

freewill or the ability to make independent decisions. As sociologists, we understand that the choices we have available to us are often limited by larger structural constraints.

a micro-level theory that emphasizes the importance of meanings and interactions in social life.

a framework that explains how the meaning of something is dependent on our social relationships.

individuals or institutions that socialize people.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

the people that are being socialized.

anything physical or tangible that people create, use, or appreciate that has meaning attached to it.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

preparation for future life roles.

a process through which people unlearn previous socialization, while being socialized by new individuals or institutions.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.