5.5 Organizations

Jennifer Puentes; Matthew Gougherty; and Aimee Samara Krouskop

We live in a society of organizations (figure 5.8). Tasks that were previously accomplished by informal groups are now done by large bureaucracies (Perrow 1991). On most days, we interact with a variety of organizations. Take, as an example, going to the store to buy groceries. Public organizations make sure the roads we use to get there are maintained and that the food being sold is safe to consume. The grocery store, typically a private organization, ensures the store is properly stocked and staffed by helpful employees. The grocery store or chain is relying on other organizations to produce and supply food. If you use a credit card to pay, you were at some point approved for the card through a bank and met certain criteria to be eligible. The grocery store may donate expiring groceries to a food bank, a nonprofit organization. In this section, we will explore some of the different types of organizations that exist in our society and how they are structured.

Types of Organizations

Sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1975) posited that formal organizations fall into three categories. Normative organizations, also called voluntary organizations, are based on shared interests. As the name suggests, joining them is voluntary. People find membership rewarding in an intangible way. They receive non-material benefits. An intramural sports team and a community organization focused on the arts are examples of normative organizations.

Coercive organizations are organizations that we must be coerced, or pushed, to join. These may include a prison or a rehabilitation center. Symbolic interactionist Erving Goffman states that most coercive organizations are total institutions (1961). A total institution is one in which inmates or military soldiers live a controlled lifestyle and in which total resocialization takes place.

The third type is utilitarian organizations, which, as the name suggests, are joined because of the need for a specific material reward. High school and the workplace fall into this category—one is joined in pursuit of a diploma, the other to make money.

For-Profit, Public, and Nonprofit Organizations

Another way to think about the types of organizations is to explore whether they are for-profit, public, or nonprofit. Sociologists argue that there are essential differences between markets and politics, which helps create the difference between for-profit and public organizations. Political authority can be a useful, inexpensive means of control. For example, it may be cheaper to have laws in place and get people to willingly stop at red lights than to try to figure out a market-based compensation system to induce people to stop. Markets, on the other hand, tend to be flexible and efficient. For-profit organizations operate in competitive markets where they seek to maximize profits.

However, for-profit organizations operating in a market can have difficulties handling some of the problems governments have to deal with. There can be unintended consequences from market exchanges. Some costs of market exchanges end up affecting those that are not part of the exchange. An example could be a factory polluting the air or water in the surrounding community. As a result, it might make sense for the government to regulate air and water quality. In other instances, there might be some services and goods that benefit everyone, but for-profit organizations do not want to provide them. For example, in the Northwest, it was not profitable for private companies to provide electricity to rural areas. In response, public utilities developed to help distribute electricity to those areas.

In analyzing public organizations, a variety of authors have explored the importance of public values as a rationale for government. Usually, these values have something to do with obligations toward the public. Intertwined with the idea of public values is the belief that people who work in public organizations have a different motivation for their work, called public service motivation. These motivations are seen as different from those that motivate people to work in the private sector. At the broadest level, public service motivation is characterized as an altruistic motivation to help and serve other people (Rainey and Steinbauer 1999).

Nonprofit organizations (or the nonprofit sector) include a wide range of organizations (figure 5.9). Generally, they are defined as being neither private organizations nor public organizations, though the exact boundaries between these types of organizations can be blurry. For example, in the United States, nonprofit organizations commonly include museums, orchestras, schools, universities, adult education organizations, research institutions, policy think tanks, health organizations, mental health organizations, human services, environmental and natural resource organizations, local development and housing organizations, and many additional types of organizations (Anheier 2005).

There are a variety of ways to define nonprofit organizations, but let us focus on the legal definition. This may be the simplest and easiest way to define a nonprofit. In the United States, nonprofit organizations are defined by the Internal Revenue Code. Although there are around 20 different types of nonprofits, a majority of the nonprofits in the United States are 501(c)(3) organizations or 501(c)(4) organizations. Both types of organizations are exempt from taxation. To qualify as such a 501(c)(3), the organization has to pass three tests: an organizational test, a political test, and an asset test. If they pass those tests, they can receive contributions that are tax deductible (Anheier 2005).

International Organizations

Organizations exist at the regional and international levels as well. For example, our global trade and financial systems run on a set of organizations. These international trade and financial systems were catapulted into existence after World War II. In response to the political instability that led to the war and the failure to deal with economic problems after the First World War, a system of global monetary management was created requiring that payments between countries be defined in relation to the dollar.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established to promote greater cooperation among countries to prevent currency wars. It exists today, monitoring exchange rates and providing loans to nations in debt. The World Bank was created to meet the need for post-WWII reconstruction and development of Europe. Today, the World Bank focuses on development, particularly of infrastructure such as dams, electrical grids, irrigation systems, and roads.

Several other global organizations have been shaped to support countries in crisis, especially during or after war. These organizations deliver foreign government assistance or humanitarian aid and development. The U.S. government also directs and funds development initiatives through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) abroad. Agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Department of Defense (DoD) implement the goals of the larger U.S. development initiatives.

International organizations dedicated to humanitarian relief, foreign assistance, and development include the many branches of the United Nations, the World Health Organization, Doctors without Borders, and the International Federation of the Red Cross.

Another set of international organizations is related to militarism and policing. These bodies also have a dual role of supporting the implementation of humanitarian ideals and defending national interests. One example is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), an intergovernmental military alliance between 28 European states, the United States, and Canada. It was set up in the aftermath of World War II, with member states agreeing to defend each other against attacks by third parties. The United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) is another example; it works to protect civilians, prevent conflict, reduce violence, and strengthen security for countries in turmoil.

Organizational Structure: Bureaucracy and Collectivism

Most days you probably have to interact with bureaucracy of some sort. Bureaucracies are organizations that have a clear division of labor, a hierarchy, and formal rules and procedures. You encounter them when you engage with your college or go to a grocery store or chain restaurant. Although he was writing over 100 years ago in Germany, Max Weber identified bureaucratic organizations and their spread across the globe as one of the key features of modern societies.

Weber argued that you can identify a bureaucracy by looking for several distinct characteristics. In a bureaucracy, there is a systematic division of labor, where it is clear who does what. Using your college campus as an example, you can identify different jobs that people engage in to make your college experience possible. Your professors teach you, information technicians make sure your course websites are functioning properly, and a registrar releases the schedule of classes and helps you enroll in courses.

According to Weber, the employees in a bureaucratic organization should be promoted and selected based on their professional or technical competence. This means your professors should have credentials and knowledge relevant to the courses they are teaching. Similarly, the people in the information technology office should be knowledgeable about learning technology.

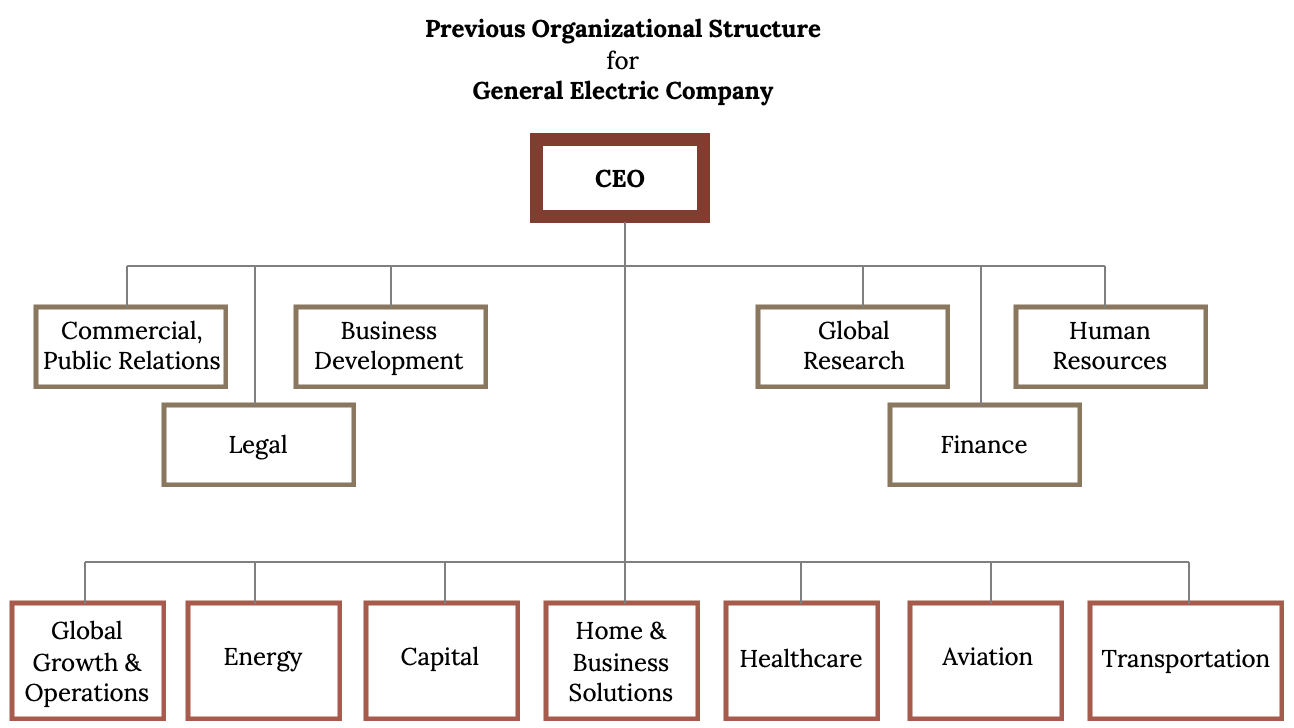

Bureaucracies are also hierarchies with job positions arranged in relationship to each other. For most organizations, their organizational chart will give you a sense of which positions are above or below others (figure 5.8). Most colleges have a university president, who is overseen by the board of the college, at the top of their hierarchy. Below the president is the provost, below the provost are the deans of the colleges, below the deans are the department chairs, and below the department chairs are the faculty.

Bureaucracies also have formal, written rules that guide decision-making. Rather than making decisions based on the arbitrary whims of those in power, there are formal procedures that should be followed. Colleges have constitutions that outline some of these rules. As a student, you also face particular rules about maintaining a certain grade point average, course sequencing, taking required courses, and meeting certain college requirements. A lot of these rules are written in the student handbook and course catalogs.

Finally, Weber argued that recordkeeping on decisions, rules, and other organizational activities was a feature of bureaucracy (figure 5.10). As you may suspect, most of this record-keeping is now done digitally. When the college board has meetings, a public record of the agenda and meeting minutes is typically made available. As students, there are records of the courses you have taken and your grades.

It is important to note that these characteristics are part of an ideal type, meaning that in real life organizations fall on a continuum of bureaucratization. It is a question of the degree of bureaucratization. Generally, as organizations age and grow in size, they tend to adopt bureaucratic elements.

While bureaucracy provides an orderly way to run an organization, it also has some limitations. Sometimes bureaucracies will lead to top-heavy management, with a large number of employees at the top of the organizational hierarchy; in other words, administrative bloat. These employees often are more engaged in managing the organization than directly involved in what the organization is supposed to be doing. In higher education, there have been concerns about the increasing number of upper-level administrators who are disconnected from the primary goal of such organizations, which is education.

Another issue bureaucracies can face is that decision-making can become centralized, with decisions made at the top and then pushed down. Employees then have little input in what is happening in the organization. This can lead to feelings of alienation and dissatisfaction. With low morale, there are few incentives for employees to be creative or devoted to their work.

Bureaucracies have become so taken for granted, it is hard to imagine other ways to run an organization. Yet, there are collectivist organizations that are more concerned with pursuing their mission or values. These organizations are essentially the opposite of bureaucracies. Most bureaucracies are focused on achieving a rational goal, such as maximizing profits.

In collectivist organizations, positions in the organization can rotate and be assigned based on the member’s interest. Someone does not have to be an expert in a particular area to have something worthy to contribute. Decision-making in collectivist organizations is not confined to those at the top. Decisions are often made collectively and democratically, enabling all participants in the organization to have a say. Some of these organizations engage in consensus decision-making (Chen 2009).

In contrast to bureaucracies, whose rules can proliferate and be difficult to change, rules in collectivist organizations are flexible. In the United States, organizations in the civil rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s tended to adopt more collectivist types of organization.

There are limitations to how collectivist organizations operate. Sometimes their efforts can become diluted, and too much time can be spent discussing what the group is rather than accomplishing a task. Collectivist organizations may choose leaders based on informal relations, such as who is more charismatic or has the most personal connections. Activities within the organization can also become misdirected, with more time focused on disorganization than pursuing the goals or mission of the organization (Chen 2009).

Examples of collectivist organizations include mutual aid groups that developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. These groups provided support to people in their communities during the early stages of the pandemic. Informal and largely ad hoc, these groups were a bottom-up response to the challenges people faced. Members of the organizations engaged in a range of activities, including providing people with meals, going grocery shopping for people who were at higher risk, providing childcare and pet care, and raising money for those most impacted by the closing down of certain industries. These types of organizations proliferated in communities the government has typically overlooked, including Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities (Toletino 2020; Hastings 2021).

In the real world, organizations combine elements of collectivist and bureaucratic organizations. In doing so, they can overcome some of the weaknesses of each type of organization. Burning Man is an organization that has successfully balanced these approaches (figure 5.11). Initially starting as a collectivist organization, Burning Man later incorporated bureaucratic elements, which provided some stability (Chen 2009).

Organizational Isomorphism

Within organizational sociology, one of the primary questions has been, “Why do organizations tend to look so similar?” Organizational sociologists refer to the process by which organizations come to look similar and homogeneous as isomorphism.

Powell and DiMaggio (1983) identify three different mechanisms of isomorphic change. Coercive isomorphism is when an organization changes itself as a result of direct or indirect pressure from another organization. Coercive isomorphism results from political influences and issues surrounding legitimacy. For example, a government mandate, such as putting into place pollution controls, can cause coercive isomorphism. Further, the common legal environment influences organizations. As we saw with the example of the tax status of nonprofit organizations, legal requirements can be imposed by the government.

Mimetic isomorphism occurs when organizations model themselves after other organizations, particularly organizations they view as successful or more legitimate. For example, some universities will model what they do after what is occurring in various Ivy League schools.

Normative isomorphism derives from the shared professional norms and standards that guide the work of professionals in organizations. Professionals bring those norms and standards into organizations, thereby shaping the organizations.

A Closer Look: Racialized Organizations

As you may have gathered from the title of this section, organizations are not race-neutral bureaucratic structures. Organizations play a role in the social construction of race and ethnicity.

Sociologist Victor Ray developed a theory of organizations to explain how they are not race-neutral. In his theory of racialized organizations, Ray (2019) argues there are ways of thinking that connect organizational rules to social and material resources. There are four main ideas to this theory:

- Racialized organizations enhance or diminish the agency of racial groups.

- Racialized organizations legitimate the unequal distribution of resources.

- Whiteness is a credential.

- Racialized decoupling of formal rules from organizational practice (Ray 2019).

We can use the racialized theory of organizations to understand how state policy and individual attitudes are shaped by organizations. By understanding organizations as a site of racial inequality, we are better able to identify the internal and external sources of change that need to occur to work toward equity.

Licenses and Attributions for Organizations

Open Content, Original

“A Closer Look: Racialized Organizations” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“International Organizations” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Organizations” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Types of Organizations” is from “6.3 Formal Organizations” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Changed the examples of normative organizations. Edited for consistency and clarity.

Figure 5.8. “GE Organizational Structure” from “Why Organizational Design” by Kindred Grey, Strategic Management is adapted from Mastering Strategic Management and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.9. “Man in Black T-shirt hold a Coca Cola Bottle: Community Power” by Joel Muniz is shared under the Unsplash License.

Figure 5.10. “Assorted Files” by Viktor Talashuk is shared under the Unsplash License.

Figure 5.11. “Pulpo Mechanico at Burning Man 2019” by jurvetson is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

organizations that have a clear division of labor, a hierarchy, and formal rules and procedures.

organizations we are forced to join.

a process through which people unlearn previous socialization, while being socialized by new individuals or institutions.

organizations we join based on seeking a material reward.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

organizations concerned with pursuing their mission or values. Often the opposite of a bureaucratic organization.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a process by which organizations come to look similar and homogeneous.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

the idea that race is more meaningful on a social level than on a biological level.

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

theory that explains how organizations are not race-neutral. In this theory racialized organizations are seen as enhancing or diminishing the agency of racial groups.

freewill or the ability to make independent decisions. As sociologists, we understand that the choices we have available to us are often limited by larger structural constraints.