6.2 What Is Culture?

What comes to mind when you hear the word “culture”? Beliefs? Symbols? Art? Music? Values? While our answers may vary, there are a lot of different ideas attached to the word “culture.” As cultural critic Raymond Williams explained, culture is “one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language” (Williams 1976:76). There is no correct or definitive meaning attached to the word “culture.” It is an ambiguous term, whose meanings change depending on time and context.

The word began as a noun connected to growing crops and livestock (cultivation). This was later broadened to encompass the human mind or spirit, and the idea of a cultivated person or cultured person emerged. Within academia, several traditions to study culture have emerged.

Humanities

One approach to the study of culture is based in the humanities. Here culture is taken as “The best that has been thought and known” (Griswold 2004:4), in other words, the wisest and most beautiful human expressions. This largely ends up confining the meaning of culture to the arts and literature, religion, meanings and values, and intellectual life. It is seen as separate from the rest of society. This is culture with a capital C. This has several implications.

This approach leads to the evaluation of some cultural works as being better than others. Generally, in this tradition, “high culture” like art and opera are understood as culture. Ultimately, this ends up producing a rather elitist view of culture and privileging European culture over culture from other places. In other words, it is ethnocentric. Ethnocentrism means to evaluate and judge another culture based on one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism is believing your group is the correct measuring standard, and if other cultures do not measure up to it, they are wrong.

Since culture is defined as a narrow range of elite objects, there is a fear it is fragile. As a result, it can be lost or destroyed, and therefore it must be preserved. Educational institutions, archives, libraries, and museums aid in that preservation. Finally, since culture in this approach is something so unique and special and removed from everyday life, it does not make much sense to critically analyze it. This can lead to a downplaying of a cultural object’s economic, political, and social dimensions (Griswold 2004).

Social Sciences

In the social sciences, a broader definition of culture developed, where culture was understood as a “people’s entire way of life.” This emerged from nineteenth-century anthropology and emphasized lived experience. In this tradition, there is not one culture, but multiple cultures. Instead of engaging in some of the elitism and ethnocentrism of the humanities approach, the social sciences try to take a culturally relativistic perspective. Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards, and not in comparison to another culture.

The social scientific understanding of culture has several implications. First, this is an expanded definition of culture, from the best/European culture to culture as a complex whole. This includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs, and other capabilities and habits acquired by people within a society. It includes material and symbolic elements of culture. Popular culture becomes something to be studied. The social sciences try to avoid evaluating cultural objects against some abstract standard (such as the “best”) in favor of understanding a culture in terms of its context.

Instead of being seen as fragile, culture is durable and persistent. Rather than being a piece of artwork that needs to be protected in a museum, culture is the way everybody lives their lives. Culture can be studied like anything else. There is nothing that makes it sacred or fundamentally different from other human activities (Griswold 2004).

Over the past century, American and European sociologists developed a wide variety of definitions of culture (Sewell 1999). At the broadest level, you could sociologically think of culture as “different ways of seeing and doing things” (Wray 2014: xix). Cultural sociology, the specific subfield within sociology, is focused on meaning-making, with a particular emphasis on symbols, categories, and interpretation. In what follows, we will explore some of these different sociological traditions for studying culture and discuss the role that the meaning-making process plays in the creation of inequalities. We begin by discussing cultural objects as a way to start thinking about the connections between culture and society.

Cultural Objects

Wendy Griswold, an influential cultural sociologist, focuses on cultural objects as a way to understand and study culture. Cultural objects are socially meaningful expressions. They can be audible, visible, physical, or articulated. They tell a story. This can range widely from slang and particular styles to beliefs and material things.

Being a cultural object is not something built into the object; it is something we as sociologists analytically decide upon. Specifying a cultural object gives us a way to grasp some part of the broader system we call “culture.”

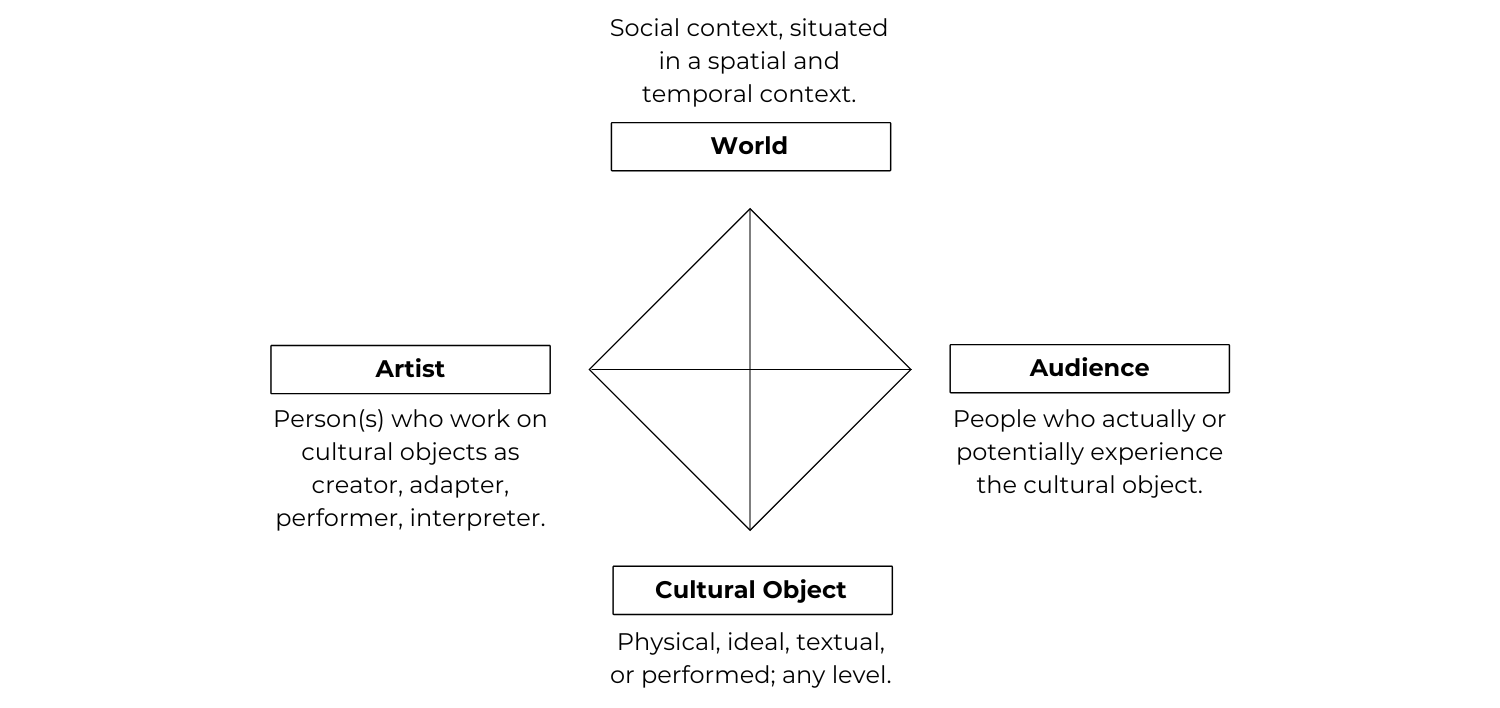

To do this, Griswold proposes a framework she calls the cultural diamond (figure 6.2). The framework begins with the cultural objects. It then looks at who created the objects (creator), which can be an individual or a group of people.

Every cultural object has a receiver, or the people that experience the object. Griswold’s diamond refers to these people as the audience. They hear, read, understand, think, participate in, recall, and actively make meaning from the objects. The cultural objects, those who create them, and those who receive them are not floating freely along. Rather, they are embedded in the social world and particular contexts. This includes the economic, political, and social patterns that occur at a particular point in time. When analyzing a cultural object, you need to consider who created it, who received it, the society it is occurring within, and the linkages between the corners of the diamond (Griswold 2004).

As an example, consider a zine associated with riot grrrl. We could look at who created it, both the individuals and groups involved in its creation. We could then explore how people accessed the zine and interpreted it. What did they make of zine? How did the audience’s social position influence their interpretation of the zine? We would then step back and focus on the larger sociological context of the time. Were there trends in politics or social movements influencing the ideas presented in the zine? Using the cultural diamond helps us narrow our focus when studying something cultural, while also allowing us to account for how the specific object is produced, consumed, and understood.

Licenses and Attributions for What Is Culture?

Open Content, Original

“What is Culture?” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.2. “Griswold’s Cultural Diamond” by Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Ethnocentrism” definition from “What is Culture?” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Cultural Relativism” definition from “Ch. 3 Key Terms” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

forms of cultural expression associated with elite groups.

to evaluate and judge another culture based on one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism is believing your group is the correct measuring standard, and if other cultures do not measure up to it, they are wrong.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards and not in comparison to another culture.

the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in mainstream society.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a framework for understanding culture that focuses on specific cultural objects, how they are created and received, and the embeddedness of these patterns within society.