6.3 Elements of Culture

Up to this point, you may have noticed that culture has a lot of different meanings attached to it. In this section, we are going to explore some of the various aspects of culture sociologists focus on. We will begin with language and symbols, and then discuss values and norms. We will then turn to how we each have a cultural toolkit that helps guide us as we move through society. Finally, we will focus on subcultures and how meaning-making can occur at a group level while still challenging mainstream culture.

Signs, Symbols, and Meaning

Sociologists often distinguish between symbolic culture and material culture. The focus on meaning-making and symbols aligns with the perspective of most symbolic interactionists. Symbolic culture includes ways of thinking, beliefs, values, and assumptions. It also includes ways of behaving, such as norms, habits, and communication. Symbolic culture often does not have a material existence. Symbolic culture allows us to communicate via signs, gestures, and language.

Signs are the building blocks of symbolic culture. Signs are symbols that convey an idea. For example, traffic signals and price tags are both signs that convey information. Numbers and letters are the most common signs, and their meaning is usually taken for granted. Gestures, or body language, are the signs that people make with their bodies. They include things like facial expressions and how much personal space people give each other during an interaction.

Language is a system of communication using vocal sounds, gestures, and written symbols. Language is probably the most significant component of a culture because it allows us to communicate with other people in interaction. Furthermore, language allows culture to be transmitted from one generation to the next.

Even as it constantly evolves, language shapes our perception of reality and our behavior. In the 1920s, linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf advanced this idea, which became known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or linguistic relativity. It is based on the idea that people experience their world through their language and therefore understand their world through the cultural meanings embedded in their language. The hypothesis suggests that language shapes thought and thus behavior (Swoyer 2003).

Words have attached meanings beyond their definitions that can influence thought and behavior. For example, in the United States, where the number 13 is associated with bad luck, many high-rise buildings do not have a 13th floor. In Japan, however, the number four is considered unlucky, since it is pronounced similarly to the Japanese word for “death.” Overall, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis emphasizes how language filters our understanding of the social world.

Let us now turn to material culture. Material culture includes, art, and artifacts, tools and utensils, machines and weapons, clothing and furniture, and so on (figure 6.3). It is anything physical or tangible that people create, use, or appreciate that has a meaning attached to it. Studying material culture can tell you a lot about a group or society. Sociologists have studied the art people hang in their homes (Halle 1996) to how buildings influence people’s actions (Gieryn 2002).

Material and nonmaterial aspects of culture are linked, and physical objects often symbolize cultural ideas. A metro pass is a material object, but it represents a form of nonmaterial culture, namely, capitalism and the acceptance of paying for transportation. Clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry are part of material culture, but the appropriateness of wearing certain clothing for specific events reflects nonmaterial culture. A school building belongs to material culture, symbolizing education, but the teaching methods and educational standards are part of education’s nonmaterial culture.

Values and Value Orientations

When exploring culture, functionalist sociologists tend to emphasize shared values. Values are a culture’s standard for discerning what is good and just in society. Values are deeply embedded and critical for transmitting and teaching a culture’s beliefs (figure 6.4). You can think back to Weber’s discussion of the Protestant work ethic in Chapter 2, in which Protestant values place an emphasis on hard work and being frugal. Values tend to exist at a rather abstract level. They are agreed upon, but how they influence everyday life can be difficult to determine.

Functionalist Talcott Parsons emphasized the importance of culture. His work, which studied values, was popular in American sociology from the late 1940s until the mid-1960s. Notably, he equated culture with values. Parsons and colleagues argued that without common values, social order would be impossible. In other words, values are at the heart of social order. Without values, people would not know how to interact with each other. Further, if values are followed by everyone in a group, they could lead to harmony. Parsons argued that there were value orientations that are systems of linked values. This linkage can be either in an individual’s mind or at the societal level. For example, a society or individual could have goal-directed values or expressive values.

Some researchers argue that countries can be grouped based on the different value orientations that they have. Based on survey research in 80 countries, the researchers found that there were four distinctive value orientations across the world: traditional values, secular-rational values, survival values, and self-expression values. Traditional values emphasize the importance of religion, family, and nationalism. These values are often contrasted with secular-rational values, which place less emphasis on religion and family life as sources of authority. Survival values tend to focus on economic and physical security. These are contrasted with self-expression values, which strongly emphasize freedom and individuality and take survival and security for granted.

In research on values orientation, the United States and most of Latin America score high on traditional and self-expression value measures. Countries in Africa and the Middle East score high on traditional and survival value measures. A large part of Europe scores high on secular-rational and self-expression values, while countries in Eastern Europe, like Ukraine, score high on secular-rational and survival values (Inglehart and Baker 2000). You have the option to view a cultural map [Website] based on this research. Specifically, focusing on the United States, some of these different value orientations may point to differences between urban and rural areas. In urban areas there is a stronger emphasis placed on self-expression values, and in rural areas, a stronger emphasis is placed on traditional values (Edsall 2022).

Some research from 50 years ago suggested there was a set of central American values (Williams 1970). These included achievement and success, activity and work, efficiency, and practicality. Some people argue this is evidence of a self-centered, individualistic culture. More recent research suggests that the values of Americans are more complicated and shift depending on social events (Cerulo 2008).

An example of this can be seen in debates around democratic values within the United States. Within the politics of the United States, there exist pro-democratic and counter-democratic values. These values can be seen undergirding different types of political actors, interactions, and institutions. In terms of democratic actors, those motivated by such values are seen as rational, calm, and realistic decision-makers. In contrast, counter-democratic actors are typically portrayed as irrational, passionate, and angry. In our interactions with other people, democratic-coded interactions are open, trusting, and based on being truthful. Anti-democratic interactions lean toward being secretive, deceitful, conspiratorial, and deferential to authority.

Democratic and anti-democratic values are also present in social institutions. Those institutions following democratic rule are regulated, law-abiding, and impersonal. This again contrasts with counter-democratic institutions, which tend to be arbitrary and focus on personal loyalty (Alexander and Smith 1993). How might this apply to contemporary American politics?

Norms

Up to this point, we have focused on rather abstract values. But what about the beliefs that guide most of our everyday interactions? Norms are the social expectations of how to behave in a situation. Norms develop out of a value system, while values operate at an abstract level, norms provide the specific dos and don’ts of a specific situation. The American political system has relied on many norms over the decades, one of which is mutual toleration. Mutual toleration involves recognizing that our political rivals are decent and patriotic. As long as our rivals follow the constitutional rules, they should have the right to govern (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018).

Some norms are officially codified and made into formal laws or rules. Others are informal and left unspoken. They are implicit and simply the “way things are done.” That said, norms are specific to a culture, and time, and are not universal.

There are different types of norms:

- Folkways are loosely enforced norms and ordinary conventions of everyday life. Examples of folkways include standards of dress or dinner table etiquette. Usually, if people don’t conform to these norms, they are considered eccentric or peculiar, but they are not seen as a real threat.

- Mores are norms that carry greater moral significance than folkways. They are closely related to the core values of a social group, and we are expected to conform to them. Breaches are treated seriously and bring severe repercussions. Examples include theft or committing fraud.

- Taboos are the most powerful type of norm. They are so deeply ingrained that violations can create a sense of disgust or horror. Examples include incest or cannibalism.

Norms are enforced through sanctions. Sanctions can be negative or positive. Positive sanctions express approval for following a particular norm. Negative sanctions express disapproval for not following a norm. In other words, it is a type of punishment. Both positive and negative sanctions are mechanisms of social control. You can find a more thorough discussion of norms, social control, and sanctions in Chapter 7.

Cultural Toolkits

Contemporary cultural sociologists have moved away from emphasizing values and norms. There are questions about how values influence people’s actions. Instead, there has been a move to understand culture as a “toolkit”—that is, culture as a “repertoire from which actors select differing pieces for constructing lines of actions” (Swidler 1986:275). Our cultural toolkits allow us to piece together and carry out different actions as we go about our days. The toolkits include symbols, rituals, habits, and stories that may conflict. Even though our toolkits might not be too coherent, people can employ their toolkits to meet most circumstances they find themselves in.

Let’s focus for a moment on the influence of habits on our actions. How often have you driven a car or ridden a bike from point A to point B without really thinking about it? How often do you regularly engage in a variety of morning rituals, such as drinking coffee, eating breakfast, and brushing your teeth? All of these habits are part of what sociologists call nondeclarative culture.

This type of culture is acquired slowly, and we usually aren’t that conscious of it. Nondeclarative culture is something we have internalized deeply and typically employ automatically in our actions. Examples include skills, dispositions, and classification schemes. This type of culture contrasts with declarative culture, which can be verbally expressed. It includes when we consciously classify the world or provide justifications or rationalizations for our actions (Lizardo 2017; Cerulo 2018). In our interactions, declarative culture tends to be slower and more deliberate. This includes our values, attitudes, worldviews, and ideologies.

Karen Cerulo (2018) provides an interesting application of these forms of culture to how we interpret and understand smells. Using focus groups, she had people smell perfumes and then reflect on them. She found that the people in her study had nondeclarative/automatic reactions to the perfumes. Drawing on their declarative culture, the participants also attached particular smells to different classes and races. In other words, she found that smell could be used by people to create boundaries between groups. In this particular study, Cerulo found that the participants associated the smells of cheaper perfumes (floral) with a lower-class standing. In contrast, the participants associated a daytime professional scent (citrus/apple/fresh) with Whiteness and being a member of the middle class. Research such as this shows how our cultural toolkits are connected to larger social forces and our social locations.

Subcultures

Let’s return to the example at the beginning of the chapter. How exactly can we understand riot grrrl given what we have discussed so far? What were some of the values and norms associated with the movement? What might be some material and symbolic cultural objects associated with the movement? Perhaps the movement might be best categorized as a subculture.

As a concept, subcultures don’t make sense unless we have a notion of dominant or mainstream culture. Dominant culture includes the values, norms, meanings, and practices of the group within society that is the most powerful. It is hegemonic, meaning it is everywhere within our society and largely taken for granted. Often in the United States, the dominant culture is the culture of the White, upper-middle class.

As an example of dominant culture, consider commercial radio stations. They typically only play a limited type of music, with songs and artists selected by various business interests that are determined to make as much money as possible. Artists not on large labels and with fewer resources might then only be played on college radio, public radio, or online.

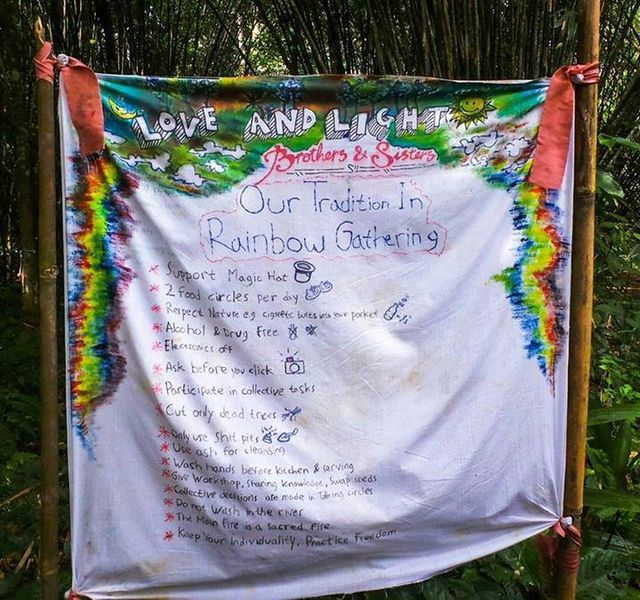

One way to define a subculture is as a group within society that is differentiated by its distinctive values, norms, and lifestyle (figure 6.5). The culture is different from the dominant culture. The people making up subcultures have distinctive ways of life, yet they exist within the larger cultural system and have contact with external cultures. Within a subculture, there are powerful and elaborate symbols and meanings. They produce cultural objects that are significant to insiders and mystifying to outsiders.

Teenagers and young people are drawn to subcultures because they provide a way for them to express themselves and differentiate themselves from their peers. Subcultures tend not to be as anchored by the institutions of adult life.

The group boundaries of a subculture can become problematic. If the group boundaries are strong, non “authentic” members might be kicked out, and it might be hard to admit new members to the subculture. If the group boundaries are fluid, the subculture might become absorbed and assimilated into mainstream culture.

When sociologically examining subcultures, style is a major theme. Style is a way to indicate membership in a subculture. Style can be defined as including image, demeanor, and argot. Image is the appearance component, which includes clothing and accessories, such as hairstyle, jewelry, and artifacts. Demeanor is made up of expression and posture. Think of how members of a subculture present themselves, and how they wear the clothing. Argot, or jargon, is the special vocabulary and language of the subculture and how it’s delivered. For example, for punk rockers a mosh pit is “an area at a punk show where punk rockers bang into each other (mosh), pogo, slam dance, etc.” (Reid 2006:26).

Activity: Analyzing Subcultures

For this activity, pick a subculture of your choosing (if you need ideas, check out this list of subcultures [Website]). Then do an internet image search for the subculture and address the following questions:

- How would you describe the subcultural style present in the images?

- What does the style say about the subculture? How might it connect to the norms and values of the subculture?

Next, think more broadly about the subculture’s style as a cultural object. What is the impact of the larger “social world” on this style?

Licenses and Attributions for Elements of Culture

Open Content, Original

“Elements of Culture” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Paragraphs on the Sapir Whorf hypothesis in “Signs, Symbols, and Meaning” are modified from “3.2 Elements of Culture” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity.

Paragraph connecting material and nonmaterial culture in “Signs, Symbols, Meaning” is from “3.1 What is Culture?” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Values” definition from “Culture, Values, and Beliefs” by Lumen Learning, Introduction to Sociology, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.3. “Cardiac Surgery Operating Room” by Pfree2014 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 6.4. “Pledge of Allegiance 1899” by Frances Benjamin Johnston is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.5. “Our Tradition at Rainbow Gathering Borneo, Indonesia” by Briegel the Soup is licensed Under CC BY-SA 4.0.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

ways of thinking, beliefs, values, and assumptions, including language and gestures.

anything physical or tangible that people create, use, or appreciate that has meaning attached to it.

an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

systems of linked values.

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

loosely enforced norms; the ordinary conventions of everyday life.

norms that carry moral significance. We are expected to conform to them.

the most powerful type of norm.

the regulation and enforcement of norms.

deeply internalized and unconscious culture.

culture that is verbally expressed.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a group within society that is differentiated by its distinctive values, norms, and lifestyle.

the values, norms, meanings, and practices of the group within society that is the most powerful.

the special vocabulary and language of a subculture and how it’s delivered.