7.3 Classical Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Alexandra Olsen

Sociologists have tried to understand why people engage in deviance or crime by developing theories to help explain this behavior. It is important to note that these theories focus primarily on why people engage in crime, why some behaviors are defined as criminal while others aren’t, and how people learn criminal behavior, rather than on deviance more broadly. The focus of these theories reflects the idea that society is much more concerned about crime than people who break other kinds of social or cultural norms.

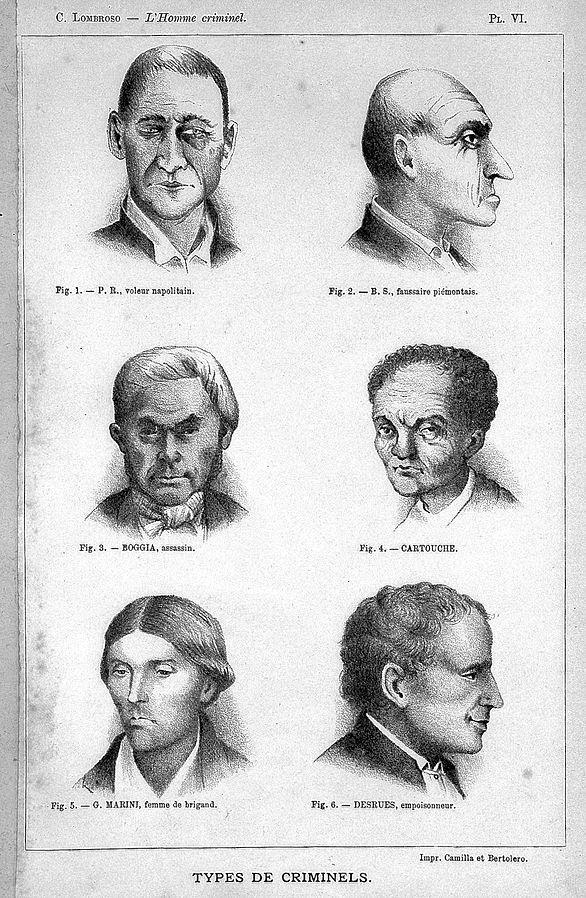

Inspired by Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, early scholars trying to explain crime turned to the concept of evolution. They claimed that certain physical features were identifying markers of criminals. Several characteristics were said to indicate criminality, including skull shape, size, body type, and facial features. For example, Cesare Lombroso (1911), the father of positivist criminology, argued that criminals were evolutionary throwbacks. He claimed that criminals can be identified by their abnormal, apelike facial and physical features. A visual depiction of these features can be seen in figure 7.4. This school of thought is closely associated with the eugenics movement, discussed more in-depth in Chapter 11. These theories were quickly disproven and have received harsh critiques for their blatantly racist foundation.

Durkheim and Functionalism

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence challenged people’s ideas about racial inequality in the United States. Moreover, Durkheim noted that when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1960 [1893]). Seeing a student given detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get detention.

Durkheim’s point regarding the impact of punishing deviance speaks to his arguments about law. Durkheim saw laws as an expression of the collective conscience, which are the beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society. He discussed how societal size and complexity contributed to the collective conscience and the development of justice systems and punishments. In larger, industrialized societies that were largely bound together by the interdependence of work (the division of labor), punishments for deviance were generally less severe. In smaller, more homogeneous societies, deviance might be punished more severely.

Modern theories have a few significant critiques of Durkheim’s perspective on crime. Sociologists have critiqued Durkheim’s argument that deviance is functional for not being generalizable to all crimes. For instance, it can be hard to argue that murder is functional for society solely because it reaffirms currently held social norms. Moreover, his idea that law is an expression of collective consciousness has also been critiqued. Conflict theorists argue that the bourgeois or elite have significant influence over political and legal institutions, allowing them to pass laws that benefit their interests and avoid harsh punishments when they commit crimes. This challenges the idea that the law reflects what society thinks is just or right.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control.

Some research supports this theory. Even today, crimes like theft or murder are more likely to occur in low-income neighborhoods with many social problems. Still, a critique of this research is that many of these studies rely on official crime rates, many of which reflect police surveillance rather than actual crime rates. For this reason, social disorganization theory does not adequately explain white-collar crimes committed by individuals living in wealthy neighborhoods, such as financial fraud or insider trading. White-collar crimes are nonviolent crimes of opportunity, often involving money. Similarly, research from a social disorganization theory often uses circular logic: an area with a high crime rate is assumed to signal a disorganized neighborhood, leading to a high crime rate (Bursik 1988).

Licenses and Attributions for Classical Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Open Content, Original

“Classical Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Alexandra Olsen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Durkheim and Functionalism” paragraphs 1 and 2 edited for clarity and brevity are from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Disorganization Theory” paragraph 1 edited for clarity and brevity is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.4. “Plate 6 of L’Homme Criminel” by Cesar Lombroso is in the Public domain, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

a violation of contextual, cultural, or social norms.

a behavior that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

the regulation and enforcement of norms.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

a theory that asserts crime occurs in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control.