8.3 Explanations of Stratification and Class

Sociologists have developed a variety of perspectives to explain stratification, class, and inequality. Some of those perspectives are critical of class-based inequalities, such as Marxism and feminism. Other perspectives, such as functionalism, come close to justifying class inequality by intellectually legitimizing the unequal distribution of resources.

Class Matters: Marx and Neo-Marxists

Since the writings of Karl Marx, sociologists have explored the relationship between social class, stratification, and work. As a quick recap of Chapter 2, Marx argued there were two social classes in capitalism: the workers (proletariat) who had to sell their labor to live, and the owners (bourgeoisie) who profited from the labor of the workers. A key difference between the classes was who owned and controlled the means of production, such as the factories and machines.

Others have expanded on Marx’s work to incorporate a wider range of factors in defining class. A neo-Marxist is someone who extends Marxist theorizing, often incorporating insights from other theoretical traditions. German-British sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf (1959) argued that Marx failed to predict numerous developments in capitalism. Specifically, he pointed to how a lot of companies were not owned and run by an individual or a family. Instead, the owners of the companies were the people who owned stock in the companies. From his perspective, this separated ownership and control.

According to Dahrendorf (1959), this separation of ownership and control allowed a new group to emerge that replaced the capitalist-owner in the workplace: managers. He also pointed to the increased differences between workers. Rather than being a unified group, workers could be divided into three groups: 1) highly skilled workers such as engineers and white-collar employees, 2) semi-skilled workers, and 3) unskilled workers. By introducing these distinctions, he argued that Marx’s categories of “owner” and “worker” were too homogeneous and unified.

Beyond challenging Marx’s conceptualization of class, Dahrendorf focused on how one’s social class position was intertwined with authority in the workplace. Authority is legitimate power. He argued that different positions in society had different amounts of authority and that authority resided in positions rather than the people occupying the positions. Authority, he asserted, always implies superordination and subordination. In the context of work, if one is in a superordinate position, those in the subordinate position are supposed to do what you say. If you are in a subordinate position and do not follow the orders, you could get a warning or a written reprimand for insubordination.

American sociologist Erik Olin Wright (1997, 2001) explained class differently. He argued that there were up to six different classes based on the relationship of the workers to the means of production, their skills and knowledge, and their authority. Like Dahrendorf, he focused on the middle classes, which do not own the means of production but also do not seem to be part of the working class.

He argued that some members of the middle class have authority over others, while the owners have authority over them. This authority involves surveilling those who are lower in the workplace hierarchy and having the ability to sanction them. Depending on where one is in the hierarchy, one’s class might be closer to the owners (think CEOs and CFOs) or closer to the workers (think lower-level supervisors).

Besides authority, Wright points to the importance of skills and knowledge in determining one’s class standing. Employees with high levels of skills/knowledge can also improve their position in the hierarchy. The control of specialized knowledge and skills by some groups of employees can make it difficult for supervisors to monitor and control them (especially if they are not experts in a particular area or subject). Overall, the middle classes are in contradictory class locations, where they are exploiters but also exploited in some ways (Wright 2001).

From the Marxist perspective, the class system is supported by a variety of ideas called the dominant ideology (Marx 1987). This ideology has several characteristics. First, it reflects the views and interests of the bourgeoisie and serves to legitimize their position in society. Second, the dominant ideology makes what is socially constructed seem natural, inevitable, and universal. For example, a Marxist would argue that wage labor is something that is used to exploit the workers and provide a profit to the rich. However, it is so commonplace that it is almost impossible to think of alternatives. Few, if any, challenge the idea of it, which makes wage labor a dominant ideology. This has not always been the case; some societies developed elaborate forms of gift-giving and barter systems.

Another example of a dominant ideology is the idea that the stratification system in the United States is a meritocracy. In other words, this dominant ideology is the American Dream, the belief in being able to work hard and get ahead. A meritocracy is a hypothetical system in which social stratification is determined by personal effort and merit. The concept of meritocracy is an ideal because no society has ever existed in which social standing was based entirely on merit. Rather, multiple factors influence social standing, including processes like socialization and the realities of inequality within economic systems. If you view the United States as a meritocracy, then you’ll see the inability to get ahead as an individual problem, rather than a feature of the stratification system.

Class and Status: Weber and Neo-Weberians

German sociologist Max Weber addressed social class differently than Marx. As you learned in the previous section, Marx and neo-Marxists have tended to assume that class is associated with one’s location in the economy. In contrast, Weber distinguished between class and status and examined the complex relations between the two in stratification systems. In doing so, Weber pointed out how stratification systems can have multiple dimensions.

First, Weber (2008) argued that property and the lack of property are the basic components of all class situations. Within each of those categories, there are a lot of different ways to have property or not. From his perspective, classes exist within the economic order.

Weber introduced the concept of status as an important component of stratification that he distinguished from class. Weber argued that status groups are normally communities based on estimations of “honor,” which is linked to a specific lifestyle. People consume certain goods associated with a specific lifestyle. These goods then signal group membership. In the United States, we have a saying for this notion: “Keeping up with the Joneses.” The assumption is that we are paying attention to our neighbor’s lifestyle and that we want to copy it. In doing so, we hope to raise, or at least maintain, our status.

While Weber tried to make a clear distinction between class and status, the relationship between the two is rather complex. Sometimes class and status overlap. In other instances, there might be a disconnect between class and status. Someone might have a particular class standing, but their lifestyle might not gain them status. For example, people who have recently become wealthy might not fit in with those whose families have been wealthy for generations. The newly wealthy might not have the right cultural tastes or dispositions to be accepted by the established elites.

Weber also identified certain economic conditions that he argued favored either stratification by status or stratification by class. When the acquisition and distribution of goods are stable, status stratification is favored. In contrast, when technological and economic transformations are occurring, class stratification becomes predominant.

Scholars influenced by Weber have further developed his ideas about class and status. As an example, British sociologist Frank Parkin provides a neo-Weberian account of class. He points to the different ways classes as groups can draw social boundaries and exclude other classes. According to Parkin, the bourgeoisie use the exclusion from property and credentials as a way to exclude the proletariat. While this is occurring, the workers attempt to gain a greater share of the valued resources. Overall, he proposes that class relations are mutually antagonistic and exist in permanent tension (Parkin 1979).

Just Rewards: Functionalism

One influential argument coming out of the structural-functionalist framework is known as the Davis and Moore hypothesis. American sociologists Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore (1942) argued that stratification was both universal and functionally necessary. Specifically, they examined the system of positions in society and how those positions attain prestige. They argued that there must be incentives so that the best individuals fill a role (or job) and that there must be a way of distributing rewards among the positions.

Davis and Moore pointed to two determinants of the position rank of an occupation in the overall occupational hierarchy. One determinant they identified is the functional importance of the job. This includes how unique the position is and whether the associated duties can be performed by other positions. It also includes the degree to which other positions and occupations are dependent on it. The greater the functional importance of an occupation, the more rewards a society attaches to it.

The other determinant is the scarcity of personnel, talent, and training. If the position requires more talent and is difficult to train for, and if there are few people who can fill the position, higher rewards will be necessary to encourage people to pursue the position.

As a result, Davis and Moore assume that the positions highest in the occupational prestige and reward system require the greatest talent and ability. Those positions, from their perspective, are less pleasurable (and the most difficult), but are more important to the survival of the system. Davis and Moore argue that those in top positions must receive rewards, otherwise they would not do their work. Those occupations would be left unfilled, and society would crumble. In contrast, the lower positions are more pleasant (and less difficult), but less important for society. Fewer rewards are then needed to get people to do those jobs.

This hypothesis has been severely criticized. Critics argue that this perspective privileges those who already have power and prestige. Davis and Moore are more or less arguing that those in high-status/reward occupations deserve their rewards, and they need those rewards for the good of society. However, this does not always hold true. For example, nurses are probably more important to society than movie stars, but movie stars receive greater prestige and rewards.

Is this process for determining rewards meritocratic? Critical sociologists point to how high-status professions are intertwined with people who already have power. Credentials are used to exclude and access to those credentials/education system is highly influenced by race, class, and gender. Furthermore, most professions have been dominated by White men from upper-middle-class backgrounds.

Gender and Class: Feminism

As we explored in Chapter 2, there are a variety of feminisms. Several of these varieties deal specifically with social class and were influenced by Marx’s theorizing about social class. From these perspectives, class becomes a starting point to better understand the complex relations between gender, race, and exploitation.

Feminists point out that Marx’s analysis of class applies largely to men. It might explain some class dynamics, but it largely overlooks the experiences of women, particularly in the workplace and the home. In the workplace, given the laws in the nineteenth century, the wages of married women technically belonged to their husbands. In addition, any labor outside of the home was paid a low wage. As a result, women helped make up a reserve army of laborers who were hired when the capitalists needed workers and fired when they did not.

In the home, wives and mothers engaged in unpaid labor. This work remains crucial for capitalist economies. Unpaid labor helps maintain the homes of the bosses and workers, while also helping create the next generation of bosses and workers. In pointing out these gendered differences related to class, Marxist feminists showed the interconnections between capitalism and patriarchy (Lorber 2010). Later, third-wave feminists pointed out how this analysis of gender and class overlooked the influence of race. We’ll discuss the different waves of feminism in Chapter 9.

Class and Colonialism: Postcolonial Theory

As was noted before in our brief discussion of settler colonialism, contemporary stratification systems and their histories are closely tied to colonialism. Several scholars, such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon provided a class analysis of these dynamics.

Du Bois analyzed capitalism in the United States after the Civil War. He argued that capitalism was further concentrated in the hands of the few during this time. Big businesses exerted economic and political control over the United States, a condition he called super-capital (Du Bois 1935). He also provided a theory of imperialism and showed how White supremacy originated in capitalism and colonialism (Wendland-Lu 2020). According to Du Bois, imperialism led to enormous profits for the imperialist countries. European countries, rather than wanting to export their surpluses, coveted the raw materials and cheap labor of African countries. Within both the imperialist countries and the colonies, the capitalists dominated (Du Bois 1945).

Fanon wrote about the Algerian experience of colonization by the French. Fanon argues that it is the landless peasants and dispossessed of the towns surrounding cities (lumpenproletariat) that are the true agents of revolutionary change in colonized countries, rather than the industrial working class. He described the class as desperate and susceptible to being co-opted by counterrevolutionary forces. As a result, he argued that the education of this class should be part of any revolution (Fanon 1961). Among the people being colonized, Fanon argues a comprador class is likely to emerge. These are local elites/bourgeoisie who want to be part of the colonizing/dominating class and align themselves with the colonizers. They have a vested interest in the occupation and do not favor a radical restructuring of society (Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin 1998).

A Plethora of Classes: Social Mobility and Status Attainment

Other sociologists understand social class differently. In particular, they argue that the dividing lines between class categories are too broad and do not reflect the modern stratification system. Instead, some argue that it is better to focus on the small gradations in income, status, or prestige. Such approaches tend to rely on 1) prestige scales based on people’s evaluations of an occupation’s standing, and 2) scales that combine occupational income and education (Grusky and Ku 2008).

Scholars who use these approaches tend to focus on socioeconomic mobility, the movement of people between classes and occupations. There are a variety of different forms of mobility:

- Intergenerational mobility is the movement between classes that occurs from one generation to the next. This occurs when a child pursues an occupation different from that of their parents.

- Intragenerational mobility is the movement between social classes that happens during an individual’s lifetime. It occurs when a worker moves from one employer or occupation to the next, and there are changes in the rewards, prestige, and status.

- Upward mobility is movement into more prestigious, better-paid, or responsible positions.

- Downward mobility is the movement into less prestigious, less well-paid, or less responsible positions.

Licenses and Attributions for Explanations of Stratification and Class

Open Content, Original

“Explanations of Stratification and Class” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Paragraph on meritocracy in “Class Matters: Marx and Neo-Marxists” is modified from “9.1 What Is Social Stratification?” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Reframed meritocracy as part of ideology. Edited for consistency.

All Rights Reserved Content

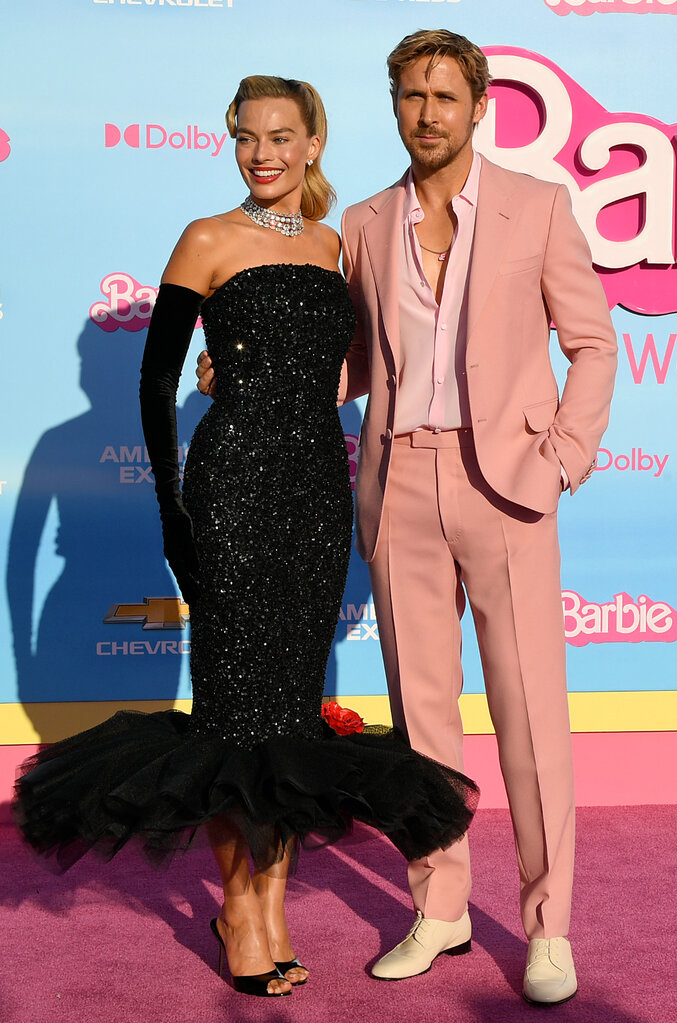

Figure 8.4. Image by The New York Times is included under fair use.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a perspective based on the idea that women and men should have equal legal and political rights. Feminism views the systematic oppression of people based on gender as problematic and something that should be changed. Also discussed as a feminist movement or a series of political campaigns for reform on a variety of issues that affect women’s quality of life

in Marx’s theory, the workers that must sell their labor.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a stratification system that is based on social factors and individual achievement. It has some degree of openness.

in Marxist theory, the dominant ideas of a time period. It reflects the interests of the owners and makes what is socially constructed seem natural.

a hypothetical system in which social stratification is determined by personal effort and merit.

a society’s categorization of its people into rankings based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and power.

the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values.

communities based on living a specific lifestyle.

an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

an environment where characteristics associated with men and masculinity have more power and authority.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

the movement of people between classes and occupations.