9.2 Sex, Gender, and Identity

When filling out a document such as a job application or school registration form, you are often asked to provide your name, address, phone number, birth date, and sex or gender. But have you ever been asked to provide your sex and your gender?

Like most people, you may not have realized that sex and gender are not the same. However, sociologists and most other social scientists view them as conceptually distinct. Sex refers to physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics, such as height and muscularity. Gender refers to behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being a woman or a man.

A person’s sex, as determined by their biology, does not always correspond with their gender. Therefore, the terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. A baby who is born with male genitalia will most likely be identified as male. As a child or adult, however, they may identify with the feminine aspects of culture. Since the term “sex” refers to biological or physical distinctions, characteristics of sex will not vary significantly between different human societies. Generally, persons of the female sex, regardless of culture, will eventually menstruate and develop breasts that can lactate.

Characteristics of gender, on the other hand, may vary greatly between different societies. For example, in U.S. culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, sarongs, robes, or gowns are considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish man does not make him appear feminine in that culture.

Perception versus Expectation

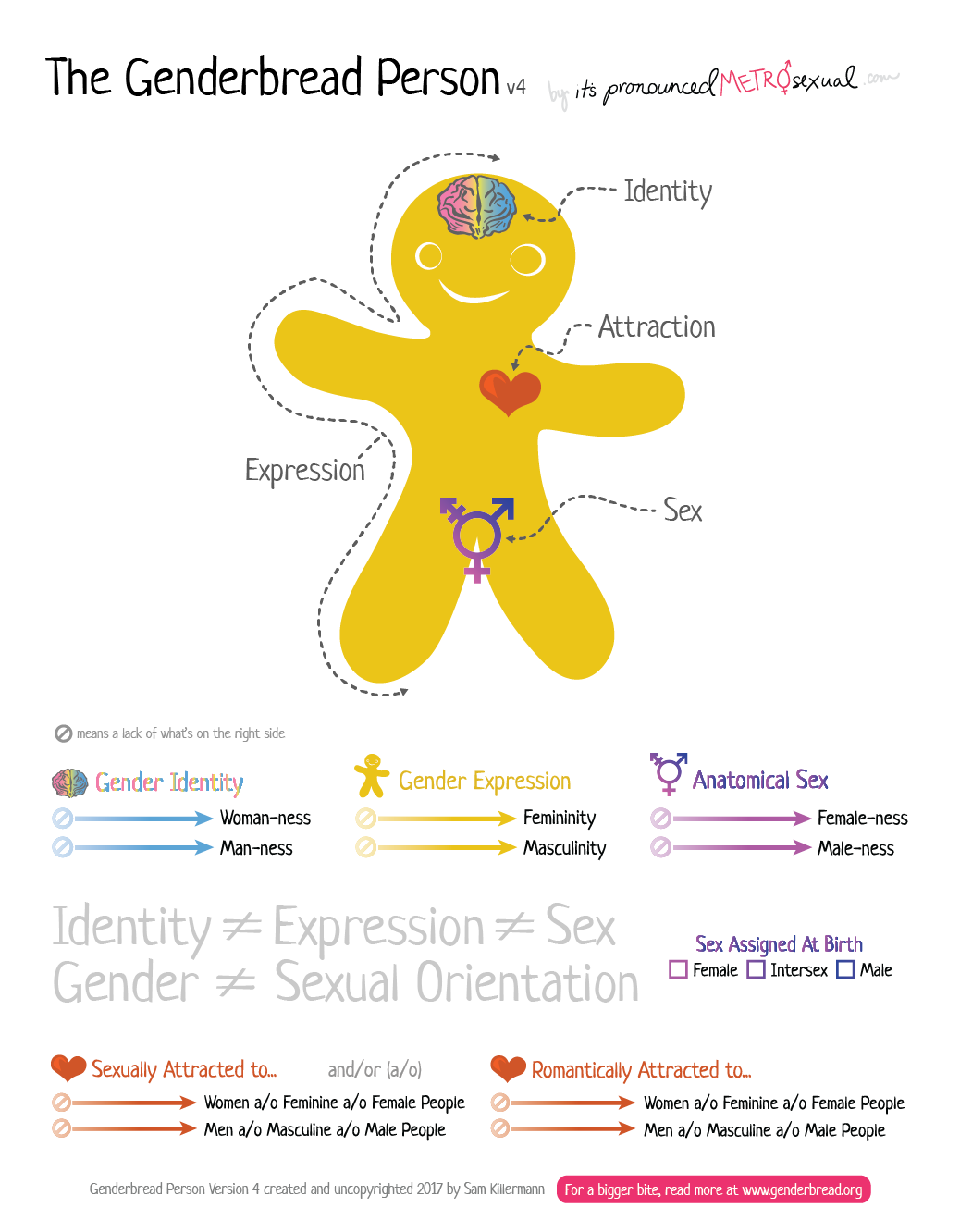

The way we use language is influenced by our culture. Culturally coded words can also impact how we perceive gender or, more specifically, roles for women and men. U.S. society allows for some level of flexibility when it comes to acting out gender roles. To a certain extent, men can assume some feminine roles, and women can assume some masculine roles without interfering with their gender identity. Gender identity is a person’s deeply held internal perception of one’s gender. Gender expression, or gender presentation, is a person’s behavior, mannerisms, interests, and appearance that are associated with gender, specifically with the categories of femininity or masculinity. The ways in which people express their gender identity are both particular to each individual and variable across cultures. This can include gender roles and categories that often rely on stereotypes about gender. Genderbread Person (figure 9.2) offers a visual to help you distinguish between gender identity and gender expression. Learn more about these concepts in the next section “Activity: Gender Identity, Gender Binaries, and Colonialism.”

Activity: Gender Identity, Gender Binaries, and Colonialism

In this short video, you will see people across the world discuss the diversity of their experiences with gender identity (figure 9.3).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqEgsHGiK-s

Please watch Gender identity: ‘How colonialism killed my culture’s gender fluidity’ [Streaming Video] and come back to answer the following questions:

- How does your culture influence your gender identity?

- How do different attitudes toward gender fluidity shape individuals’ experiences with gender identity?

- How has colonialism affected gender diversity?

The “rules” of gender are based on accepted gender roles. Gender role refers to the expected role for individuals based on society’s notions of the attitudes, behaviors, norms, and values that are appropriate for women and men. Traditionally, American culture associates masculine roles with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles are usually associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination.

Social Construction of Gender

Gender is a constant part of who and what we are, how others treat us, and our general standing in society. Gender differences are visible in different aspects of behavior, emotions, and relationships and in the organization of social institutions, such as work and family. Often, gender is divided into two major categories: women and men. The social construction of gender helps us understand how people produce differences between women’s and men’s characteristics and behavior. By understanding how gender is socially constructed, we can see how gender inequality is reproduced.

Patriarchy or a patriarchal society refers to an environment where characteristics associated with men and masculinity have more power and authority. In the evaluation of gender differences within a patriarchal society, women are ranked lower than men. Even the valued characteristics of women, such as empathy, nurturance, and care for others, are ranked lower. Because men and boys are held in higher social regard than women and girls and are granted additional advantages and rights, gender differences produce gender inequality.

The social constructionist perspective allows us to understand changes in gendered practices and shows that social norms change over time. However, change does not come easily. Many foundational assumptions of the gendered social order are legitimated by religion, taught by education, upheld by mass media, and enforced by systems of social control. From a sociological perspective, we examine how trends change over time. Historically, all infants in the United States wore gowns that were typically white. After the invention of manufacturing and mass production, we saw the use of color but pink was identified as a strong masculine color, while blue was associated with femininity (Paoletti 2012).

Some researchers suggest that the process of gender socialization begins in utero. During pregnancy after learning the sex, parents and guardians begin talking to their fetus in gendered ways (Martin 2003). Other researchers argue that children learn gender as infants. Between the ages two and three years, most children understand what sex they are and begin to identify the types of social norms they should participate in. Around this age, children develop preferences for same-sex playmates and have positive attitudes toward their own group (Martin and Ruble 2002; Shows and Gerstel 2009).

Masculinity

Masculinity involves the performance of gender shaped by society’s expectations for men. At a young age, parents of boys express concern over their children’s participation in “feminine” activities, such as wearing pink, dressing up in feminine attire, or wearing nail polish (Kane 2006). In Emily Kane’s research, outside of learning to cook and clean, parents assumed “feminine” behaviors were inappropriate for boys and often expressed distress by questioning why a particular behavior was occurring. Interestingly enough, parents who were open to gender non-conforming behavior still discouraged femininity as a way to protect their children from social disapproval. As this example illustrates, the fear of social disapproval stems from a culture that defines masculinity in opposition to femininity (figure 9.4). Boys and men are taught to avoid femininity or being perceived as feminine.

In her foundational text, Gender & Power, Connell (1987) introduces the idea that there are multiple masculinities. Forms of masculinity that are generally valued and perceived as socially acceptable in dominant culture can be extremely constraining. Hegemonic masculinity is the masculine ideal that is viewed as superior to any other kind of masculinity as well as to any form of femininity (Connell 1987; Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). Characteristics and behaviors associated with this ideal standard of masculinity may change over time (Connell 1987, 1995). However, we continue to see an emphasis placed on masculinity that aligns with characteristics of independence, aggression, competition, and toughness.

Extreme versions of hegemonic masculinity that conform to the more aggressive rules of masculinity are sometimes referred to as hypermasculinity (Wade and Ferree 2015). In our culture, hypermasculinity tends to glorify the aggression that one might associate with action movies, video games, and even some athletic performances. In reality, men are not inherently violent, but hypermasculine performances of gender make some men’s violence, aggression, and anger seem normal.

Some scholars identify an even more extreme form of hegemonic masculinity as toxic masculinity. The term “toxic masculinity” captures some of the cultural pressures placed on men to conform to hegemonic masculinity. Men may engage in risky behaviors to achieve the culturally approved standards of manhood. Psychologists argue that these standards of manhood take a negative toll on men’s mental and physical health (Iwamoto et al. 2018). Toxic masculinity can be found in both academic and popular cultural contexts. Both generally depict a masculinity that exhibits toughness, rejects anything feminine, and prioritizes power and status (Thompson and Pleck 1986; Morin 2020).

While there is debate over how much new styles of masculinity challenge hegemonic masculinity, scholars agree that our constructions of masculinity fit into a larger issue of gender inequality (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). Research on masculinities has explored a few different areas including: 1) various forms and styles of masculinity, 2) different ways scholars use the concept of hegemonic masculinity, 3) female masculinities, and 4) how power and masculinity intertwine through the lens of globalization. Some researchers argue that masculinity is no longer strictly defined against femininity. Instead, the intersections of class and race create a new line of division. For example, the class-privileged, White “new man” of the 1990s may challenge traditional depictions of hegemonic masculinity. However, this “new man” is constructed against the “macho” masculine gender display of subordinated men of color who have less power and socioeconomic status (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Messner 1994). Instead of emphasizing power dynamics along the lines of gender, we see the ways that race and socioeconomic status play a role in constructing a masculine ideal.

The notion of a “new man” comes from what sociologist Tristen Bridges refers to as hybrid masculinities. Hybrid masculinities are created when subordinated styles and displays of gender are co-opted by men with privileged identities (Bridges 2014; Bridges and Pascoe 2014, 2018). For instance, men with class privilege may participate in personal grooming practices that are traditionally perceived as feminine as a way to enhance their positions of privilege with displays of metrosexual style (Barber 2016). Rather than undermining the unequal power relations embedded in hegemonic masculinity, Bridges and Pascoe (2018) argue that hybrid masculinities conceal systems of inequalities related to gender and sexuality.

Femininity

While men’s performances of doing gender are routinely subjected to gender policing, women often have more freedom and are sometimes rewarded for performances of masculinity. Gender policing refers to the responses we receive when we violate gender rules. A “tomboy” (a girl who acts masculine) is usually regarded more positively than a “sissy” (a boy who acts feminine). Think back to Emily Kane’s research that we learned about in the masculinity section. Parents were nervous about boys’ performances of femininity and discouraged the practices, but expressed delight in their girls’ gender non-conforming behavior and even encouraged participation in traditionally male activities such as T-ball, football, and using tools (Kane 2006:156-7).

However, this does not mean that women are free of gender policing completely. Instead, the approval reflects how masculinity is perceived as more highly valued in a patriarchal society. Women are simply tapping into the characteristics that are already highly sought after and rewarded in their culture.

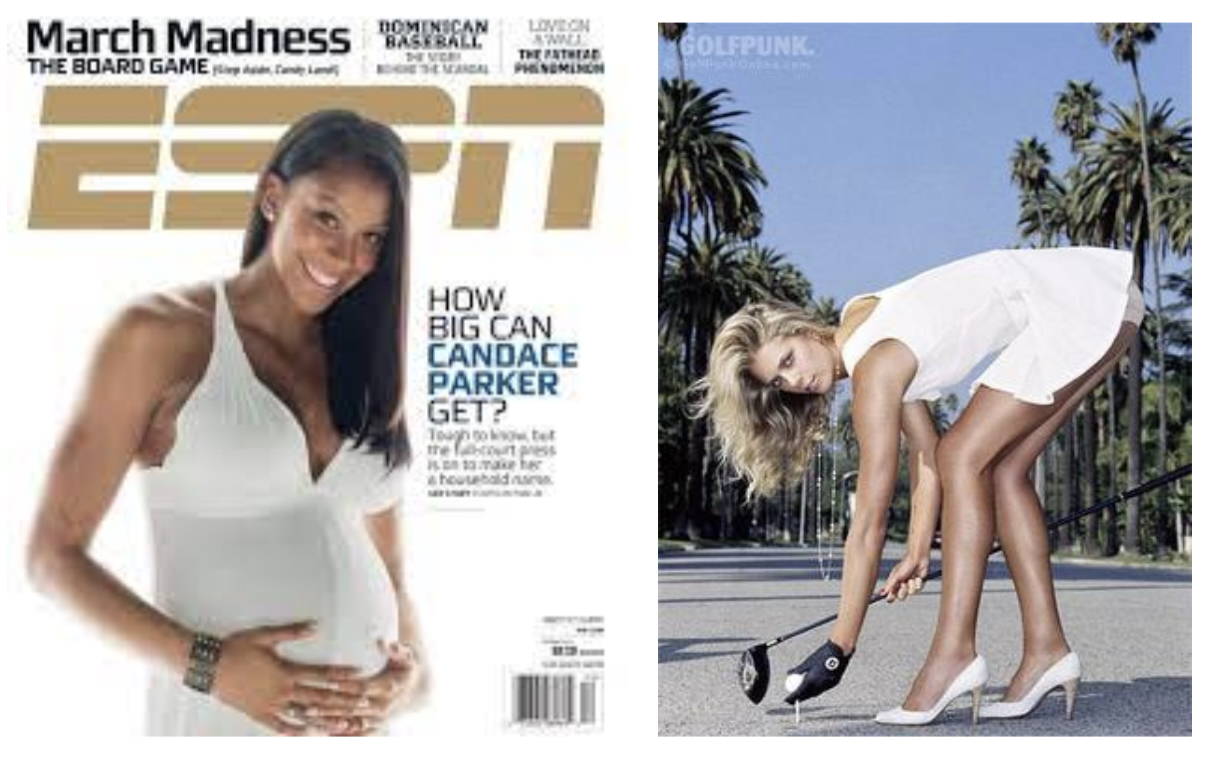

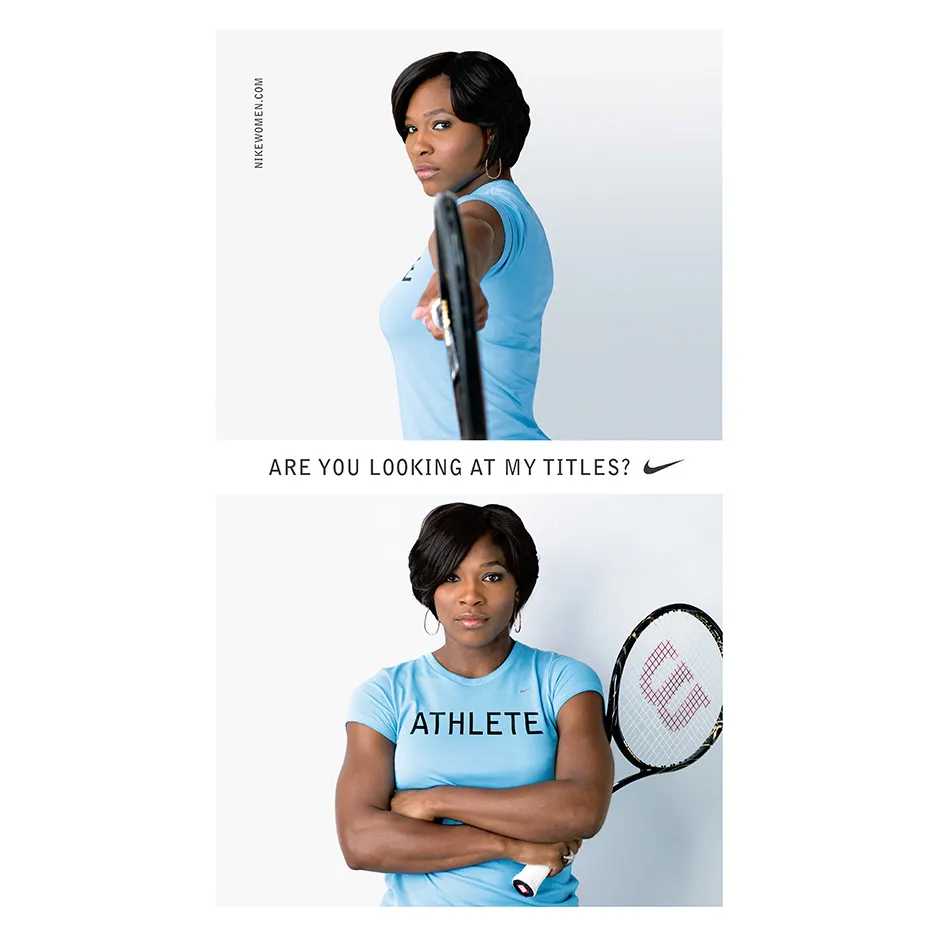

Even so, women engaging in what others consider too much masculinity will receive the same gender policing men who participate in a little femininity receive. The expectation that women learn to balance their interest in “masculine” activities and traits with a feminine gender performance is called the feminine apologetic (Wade and Ferree 2015). For example, women athletes often participate in the feminine apologetic by making efforts to appear feminine (figures 9.5A and 9.5B; 9.6), apologizing for aggression, or marking themselves as heterosexual to counter their success in sports, an arena that is often considered masculine (Davis-Delano et al. 2009). The strategy of using the feminine apologetic enables women to benefit from participating in masculinity without attracting violent gender policing (Hardy 2014).

When we examine power relations, there are some disadvantages to “doing” femininity. In dominant culture, many of the traits associated with femininity are largely devalued in society. Power is gendered, and the current construction of femininity draws on traits that are passive and show deference to hegemonic masculinity. In other words, “doing” femininity also requires the embodiment of powerlessness to some extent.

In Gender & Power, Connell (1987) also spent some time theorizing femininity, particularly the concept of emphasized femininity. Emphasized femininity is “the pattern of femininity which is given most cultural and ideological support” (Connell 1987:24). It is “defined around compliance with subordination and is oriented to accommodating the interests and desires of men” (Connell 1987:187). She argues that this version of femininity is a reaction to hegemonic masculinity, and although it has value, masculinity at large is still perceived as more highly valued. Originally, theories on femininity focused on it as a subordinated gender performance and did not expand on the ways that some forms of femininity have power over others. The limitations of this approach are evident when we consider femininity and its connections to hegemonic power relations (Hamilton et al. 2019).

Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990; 2004) extends Connell’s theorizing of femininity by incorporating an intersectional lens. She argues that hegemonic femininity is race-based, class-based, and gender-based. When women accomplish the ideals of femininity, they are contributing to oppression through what Collins refers to as the matrix of domination. Hegemonic femininities hold a powerful position in the matrix, resulting in some women receiving benefits over others (Hamiliton et al. 2019). We will examine the concept of intersectionality more in the next section.

Licenses and Attributions for Sex, Gender, and Identity

Open Content, Original

“Social Construction of Gender” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Masculinity” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Femininity” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Gender Identity, Gender Binaries, and Colonialism” is adapted from Gender identity: ‘How colonialism killed my culture’s gender fluidity’ by BBC World Service, licensed under the Standard YouTube License, and is licensed CC BY 4.0. Modifications include authoring questions and framing the activity.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Sex, Gender, and Identity” first four paragraphs are from “12.1 Sex, Gender, Identity, and Expression” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and brevity.

“Gender Expression” definition from “Wrapping Up: What Is Gender? Beyond the Binary” by Katherine Furniss, Sarah Hammarlund, Deena Wassenberg, Sehoya Cotner, Evan Nickchen, and Rachel Olzer, Evolution and Biology of Sex, University of Minnesota Libraries, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Gender Role” definition modified from “Ch. 12 Key Terms” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2. “The Genderbread Person” graphic by Sam Killerman via hues is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.3. “Gender identity: ‘How colonialism killed my culture’s gender fluidity’ [YouTube]” by BBC World Service is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.4. Photo by Ran Zheng for NPR is included under fair use.

Figure 9.5, left. Photo by ESPN Magazine is included under fair use.

Figure 9.5, right. Photo by Golfpunk is included under fair use.

Figure 9.6. Photo by Nike is included under fair use.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

a deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.

when a dominating country creates settlements in a distant territory.

the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among individuals.

the expected role determined by an individual’s sex and the associated attitudes, behaviors, norms, and values.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

an environment where characteristics associated with men and masculinity have more power and authority.

the regulation and enforcement of norms.

a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously.

the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

the values, norms, meanings, and practices of the group within society that is the most powerful.

the masculine ideal that is viewed as superior to any other kind of masculinity as well as any form of femininity.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

the idea that individuals perform gender based on the way that gender is socially constructed within their society; they are held accountable for enacting gendered behaviors. These gendered performances are expected and contribute to why we think of gendered behavior as “natural.”

the practice of judging people’s gender practices and reminding others of the rules of “doing gender.” This practice reinforces gender order and reproduces gender inequality.

the pattern of femininity that is given the most cultural and ideological support. This type of femininity involves compliance with subordination and is oriented to accommodate the interests and desires of men.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.