9.8 Social Institutions and Stratification in Work/Public Spheres

As you learned in Chapter 8, stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. There is a long history of gender stratification in the United States:

- Before 1809—Women could not execute a will.

- Before 1840—Women were not allowed to own or control property.

- Before 1920—Women were not permitted to vote.

- Before 1963—Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work.

- Before 1973—Women did not have the right to safe and legal abortion (Imbornoni 2009).

When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality but underlying effects of male dominance still permeate many aspects of society.

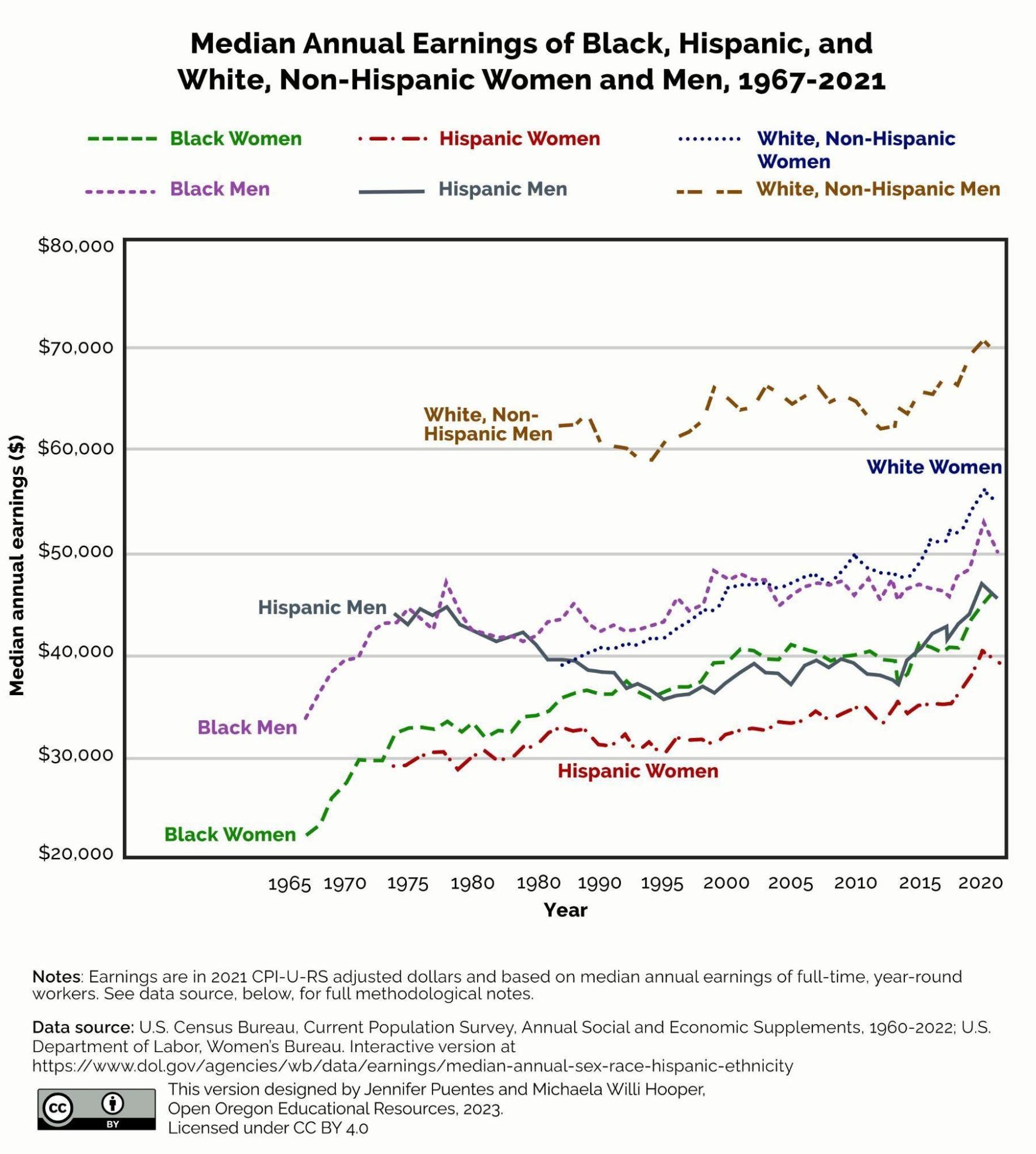

The Pay Gap

Despite making up nearly half (49.8 percent) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Even when a woman’s employment status is equal to a man’s, she will experience what’s known as a pay gap: generally, a woman makes only 81 cents for every dollar (figure 9.19) made by her male counterpart (Payscale 2020). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989). For additional, optional information, you can learn more at AAUW [Website].

Part of the gender pay gap can be attributed to unique barriers faced by women regarding work experience and promotion opportunities. A mother of young children is more likely to drop out of the labor force for several years or work on a reduced schedule than a father. As a result, women in their 30s and 40s are likely, on average, to have less job experience than men. This effect becomes more evident when considering the pay rates of two groups of women: those who did not leave the workforce and those who did. In the United States, childfree women with the same education and experience levels as men are typically paid in amounts close to but not exactly the same as men. However, women with children are paid less. Employers offer mothers a 7.9 percent lower starting salary than non-mothers, which is 8.6 percent lower than men (Correll et al. 2007). Research interviewing women shows that women in leadership positions experience ageism at every age in the workplace. Older women are routinely discounted as outdated and not worthy of advancement, while younger women’s credibility is questioned (Diehl, Dzubinski, and Stephenson 2023).

Furthermore, not all states have laws that prohibit employers from discriminating against LGBTQIA+ individuals when it comes to hiring practices and wages (Gates 2017). Survey research by Singh and Durso (2017) demonstrates that there is a high rate of discrimination for LGBTQIA+ workers. They found that 27 percent of transgender workers reported being fired, not hired, or denied a promotion because of their gender identities.

The Glass Ceiling

The idea that women are unable to reach the executive suite is known as the glass ceiling. It is an invisible barrier that women encounter when trying to win jobs in the highest level of business. At the beginning of 2021, for example, a record 41 of the world’s largest 500 companies were run by women. While a vast improvement over the number 20 years earlier, when only two of the companies were run by women, these 41 chief executives still only represent 8 percent of those large companies (Newcomb 2020).

Why do women have a more difficult time reaching the top of a company? One explanation is that there is still a stereotype in the United States that women aren’t aggressive enough to handle the boardroom (Reiners 2019). Other issues stem from the gender biases based on gender roles and motherhood that we previously discussed. Another possible explanation is that women lack executive mentors with the power to get them into the right meetings and introduce them to the right people (Murrell and Blake-Beard 2017).

Feminization of Poverty

Women disproportionately make up the majority of individuals who live in poverty across the world. The gender wage gap, the higher proportion of single mothers compared to single fathers, and the high cost of childcare create a gendered experience when it comes to living in poverty. Considering the economic situation produced by these factors, women (11 percent) are more likely to live in poverty than men (8 percent) (Fins 2020). Women in all racial and ethnic groups are more likely than White men to live in poverty. United States census data shows that poverty rates are higher for Black women (18 percent), Native American women (18 percent), Latinx women (15 percent), and Asian women (8 percent) (Fins 2020).

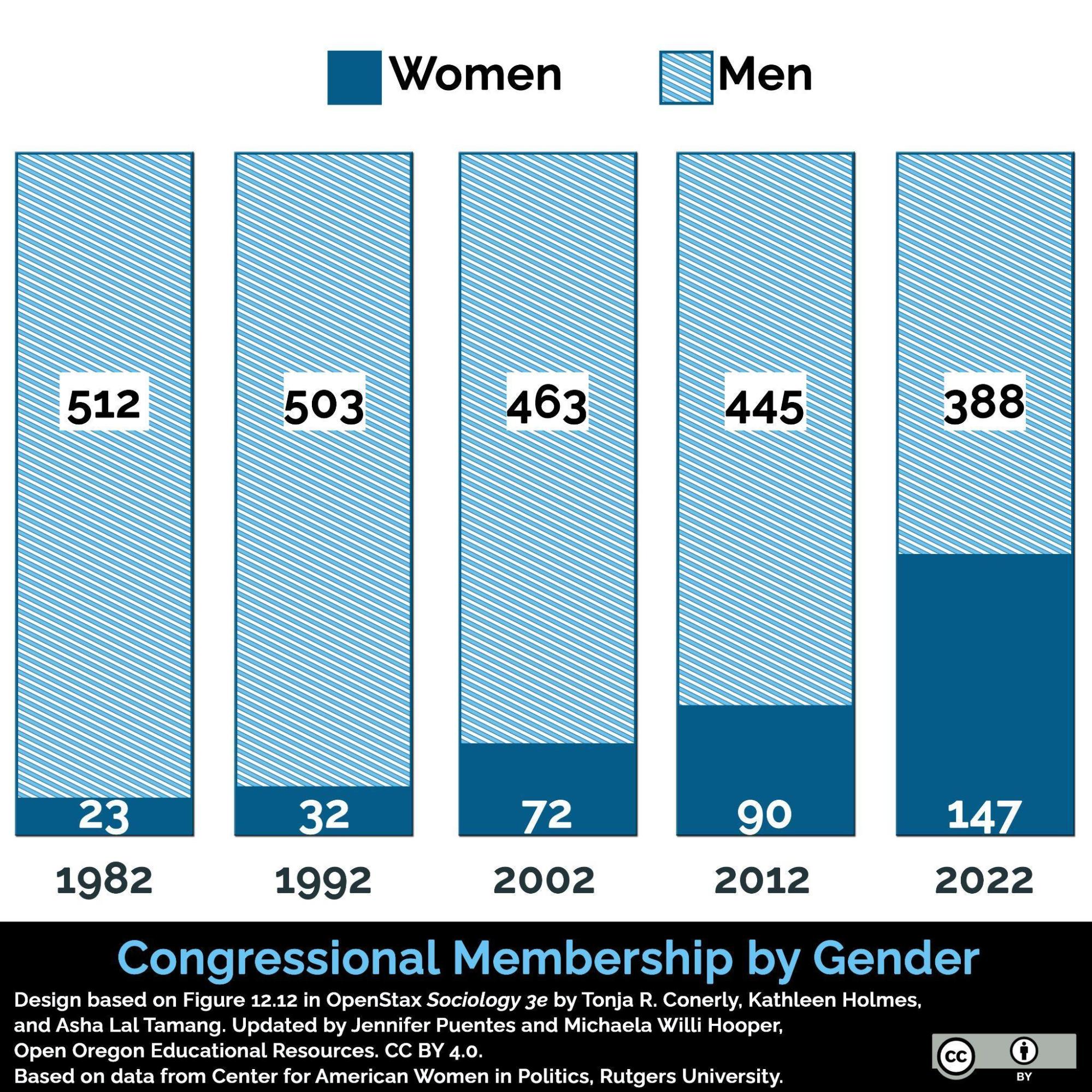

Women in Politics

One of the most important places for women to help other women is in politics. Historically in the United States, like many other institutions, political representation has been mostly made up of White men. By not having women in government, their issues are being decided by people who might not share their perspective. The number of women elected to serve in Congress has increased over the years, but it does not yet accurately reflect the general population (figure 9.20). In 2021, the population of the United States was 49 percent male and 51 percent female (Census.gov 2022), but the population of Congress was 72.3 percent male and 27.7 percent female (Manning 2022). Until the number of women in the federal government accurately reflects the population, there will be inequalities in our laws.

Women’s bodies are often brought into political conversations. Often, decisions are made regarding what is appropriate for women with little feedback from the group that is directly affected. In the next section, you will learn more about a recent court decision that greatly affects some women’s decision-making abilities today.

A Closer Look: Roe v. Wade

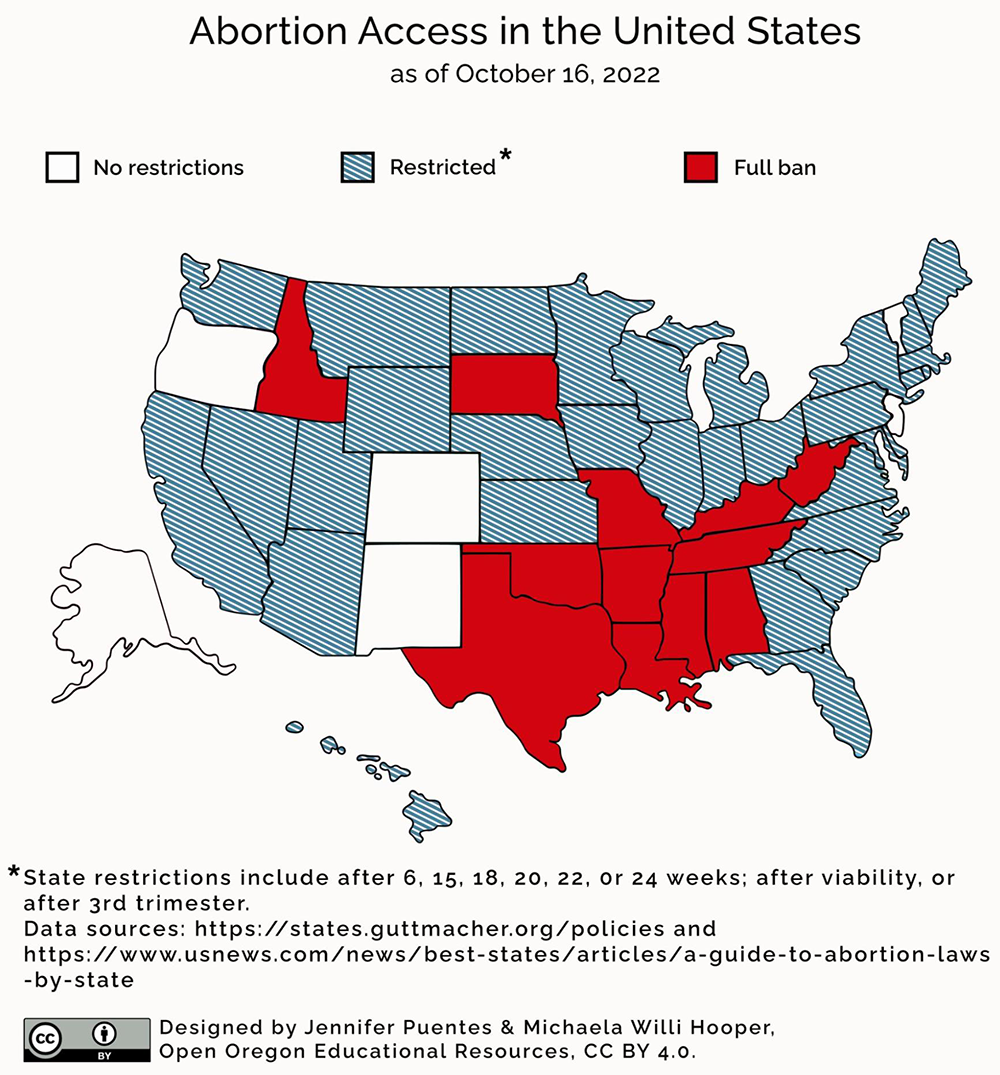

On June 24, 2022, in a 6-to-3 decision, the Supreme Court overturned the Roe v. Wade ruling that protected women’s autonomy to choose abortion. The due process clause added to the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution that provided a “right to privacy” and protected pregnant women’s rights to an abortion has changed. This decision comes at a time when data from the PEW Research Center shows that 61 percent of adults believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases (Pew Research Center 2022a, 2022b).

A decision made by nine individuals appointed by a handful of (male) presidents impacts the lives of families and fundamentally restricts women’s autonomy and choices. Now, individual states and government officials have the power to determine women’s reproductive rights (figure 9.21). Current laws and policies within individual states will make accessing safe medical procedures difficult. Several states already had laws banning abortion that predated Roe v. Wade, and others had trigger laws (bans on abortion that would go into effect with the overturning of Roe v. Wade) (Mangan 2022a). Some states have bans on abortions after six weeks of gestation. At such an early stage, many women might not be aware that they are pregnant. Others might not be able to secure doctor’s appointments within the narrow timeframe.

Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, argued that the 1973 ruling was an error made on weak arguments and an “abuse of judicial authority” (Totenberg and McCammon 2022). Dissenting Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan said that the court decision means that “young women today will come of age with fewer rights than their mothers and grandmothers . . . from the very moment of fertilization, a woman has no rights to speak of. A state can force her to bring a pregnancy to term even at the steepest personal and familial costs” (Totenberg and McCammon 2022). This ruling has significant implications for women’s positions in society—or at least for some women. As we will discuss later in this chapter, affluent women have always and will continue to have options when it comes to seeking medical care.

There are many reasons a woman may choose to get an abortion. Rather than questioning why someone might want control over their reproductive rights and bodies, it is interesting from a sociological perspective to understand how complicated this court decision becomes when we examine our current social institutions. As the dissenting justices pointed out, women will be expected (and can be forced) to carry pregnancies to term when our current work and family policies do not uniformly support family life.

In the United States, parental leave policies are limited. If workplaces offer parental leave, it is often unpaid. This can either create an additional financial burden or make time off inaccessible at a time when new parents and guardians need to adjust to the mental and physical demands that come with newborns. If eligible, employees may need to take short-term disability or use the Family and Medical Leave Act [Website], which you can explore if you wish. Government programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) attempt to offer financial support for low-income families with children, but there is still a stigma associated with participating in welfare programs (McLaughlin 2021). Eligibility requirements are restrictive and benefits are low. For example, in Oregon the current maximum monthly benefit for a family of three is $503, which you can optionally learn more about at Benefits.gov (2022)[Website]. We also should consider how this decision will impact the growing fertility industry.

Keep in mind that this discussion is intended to point out how women’s rights are now restricted. This decision disproportionately affects women of color and those with lower socioeconomic status (Dehlendorf, Harris, and Weitz 2013; Johnson 2022). The overturning of Roe v. Wade also brings into question other rulings where it was used as precedent. For example, Justice Clarence Thomas has mentioned that we need to reexamine marriage equality and contraceptive rights (Mangan 2022b). This single court decision demonstrates that gender organizes our daily lives, from how we learn to interact with others to how our laws serve to protect us.

Licenses and Attributions for Social Institutions and Stratification in Work/Public Spheres

Open Content, Original

“Social Institutions and Stratification” by Jennifer Puentes licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“A Closer Look: Roe v. Wade” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.19. “Median Annual Earnings of Black, Hispanic, and White, Non-Hispanic Women and Men, 1967-2021” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau.

Figure 9.21. “Abortion Access in the United States as of October 16, 2022” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Institutions and Stratification in Work/Public Spheres” paragraphs one through three, five, six, and eight edited for clarity, consistency, and to update content from “12.2 Gender and Gender Inequality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.20. “Congressional Membership by Gender” is adapted from figure 12.12: Breakdown of Congressional Membership by Gender by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Updated by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources. Modifications: Improved accessibility and updated data. Based on data from the Center for American Women in Politics, Rutgers University.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

the difference in earnings between men and women.

an abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. The additional “+” stands for all of the other identities not encompassed in the short acronym. An umbrella term that is often used to refer to the community as a whole.

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

a person whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not necessarily the same.

an invisible barrier that women encounter when trying to win jobs in the highest level of business.

oversimplified generalizations about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive (usually about one’s own group) but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is stupid or lazy).

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

the legal recognition of the rights of marriage regardless of one’'s sexual orientation or gender identity.