2.4 The Structure and Organization of Society

Studying social change with sociology requires focusing on how societies are structured and organized. Social structure is the building blocks or social patterns in which a society operates. It includes social institutions, status, and roles. Other elements of society that are foundational to the organization of social life are systems, cultural patterns, social facts, and socialization. Sociologists present these components differently. However, what matters is that we are influenced by them as we interact with others.

Structure of Society

To sociology lecturer Christopher Till, “Social structures are to sociologists what physical forces (such as gravity) are to physicists or what chemical elements (such as hydrogen or carbon) are to chemists” (Till 2015). They are sets of long-lasting social relationships, practices, and institutions that can be difficult to see at work in our daily lives. They are intangible social relations, but they work much like structures we can see: buildings and skeletal systems are two examples. Bones structure the human body; that is, the rest of our bodies’ organs and vessels are where they are because bones provide the structure upon which these other things can reside.

Social structure is society’s complex and stable framework that influences all individuals or groups through the relationship between institutions (e.g., economy, politics, religion) and social practices (e.g., behaviors, norms, and values). Structures limit possibility, but they are not fundamentally unchangeable. For instance, our bones may deteriorate over time, suffer acute injuries, or be affected by disease, but they never spontaneously change location or disappear into thin air.

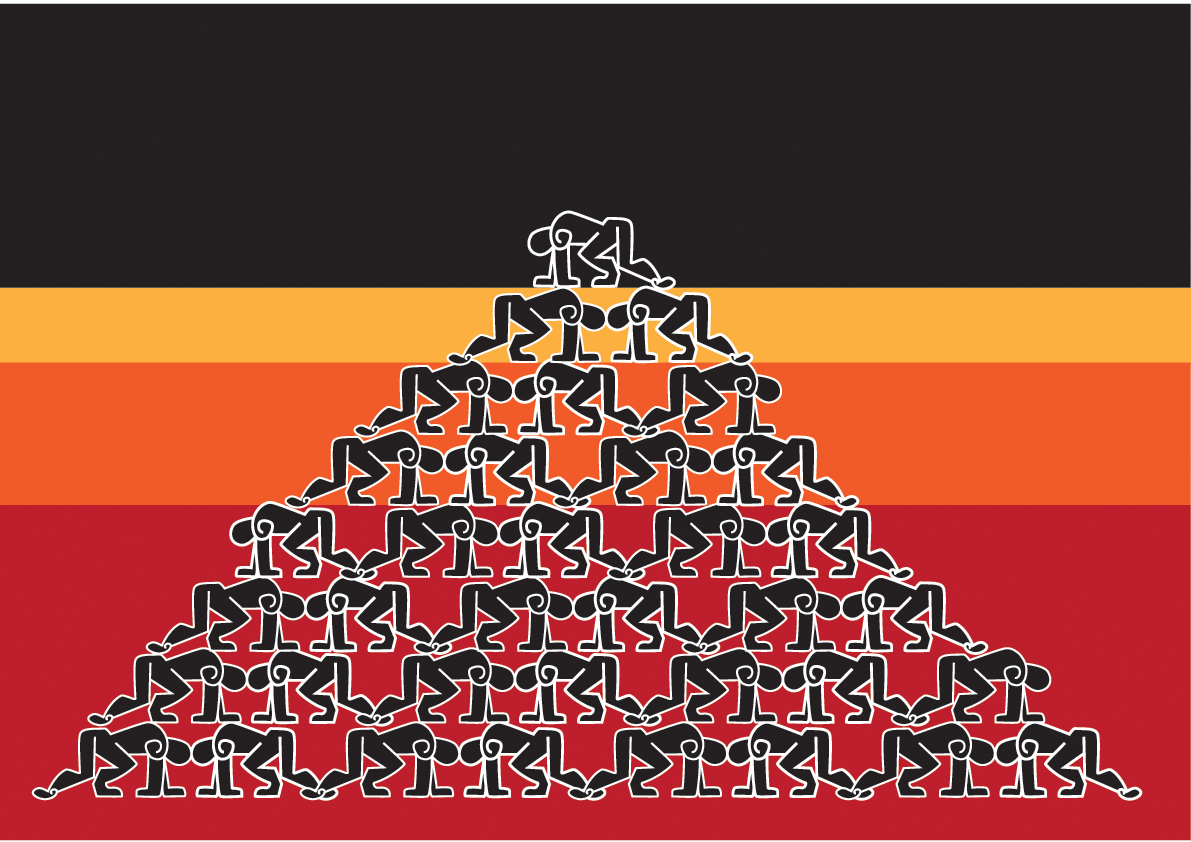

Social structure almost always involves a hierarchy among people, as society’s patterned arrangements both limit and create opportunities for individuals. Typically, more opportunities are available for people who share similarities with those in positions of power (figure 2.10).

Institutions

Social structure is made up of many institutions. In Chapter 1, we defined institutions as “large-scale social arrangements that are stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.” Examples of those institutions and related needs include the following:

- Government serves the need of society to establish laws.

- Media serves the need of society to establish methods of communication.

- Family serves the need of members of society to reproduce, raise children, and care for elders.

These arrangements reproduce themselves and show patterns across time and geography. Our institutions are often interconnected. For example, the economy, family, and education are separate social institutions that regularly intersect. Available work opportunities depend on the state of the economy and access to education. The arrangements of our families, including their economic status, may create or limit opportunities to pursue higher education.

Click through the Prezi presentation made by Elizabeth Berrios (figure 2.11) to learn more about some main institutions sociologists study: family, health and welfare, politics, economy, education, and religion. Clicking through each institution will also allow you to explore its functions.

https://prezi.com/p/embed/v_ib6shcpyar/

It’s important to distinguish sociology’s use of the term “social institution” from the more common use of “institutes.” Institutes refer to organizations, establishments, or foundations devoted to promoting a particular cause or program. Specific colleges and research centers are often called institutes.

Social institutions are the elements of a social structure, the parts of social life that direct possible actions. To say these institutions direct possible social action means that within the confines of these spaces, there are rules, norms, and procedures that limit what actions are possible.

Roles and Status

People employ many types of behaviors in day-to-day life. Roles are patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status. Currently, while reading this text, you are playing the role of a student. However, you also play other roles in your life, such as “daughter,” “neighbor,” or “employee.”

These various roles are each associated with a different social status, the rank or position that one holds in a group. Social status is also the prestige, responsibilities, and benefits attached to one’s position in society. Some statuses are assigned—ones you don’t choose, like being a son, an elderly person, or a female. Others, called achieved statuses, are obtained by choice, such as becoming a criminal, a self-made millionaire, or a nurse.

Watch either of the two 2.5-minute videos, published by Storycorps, an organization dedicated to “helping us believe in each other by illuminating the humanity and possibility in us all”: “The Family Equation” [Streaming Video] (figure 2.12) or “My Aunties: Father Figures” [Streaming Video] (figure 2.13). As you do, how many statuses and roles can you see portrayed in the stories? How did those roles change when the parents and children faced challenges?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OKQI2ZCqw3s&t=1s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5HWmzE0NWE

As a daughter or son, you have a different status than as a neighbor or employee. One person can be associated with a multitude of roles and statuses. Even a single status, such as “student,” has multiple roles. As such, a role is expected of you as a student (at least by your professors); this role includes coming to class regularly, doing all the assigned readings, and studying the best you can for exams. Status refers to the rank in social hierarchy, while the role is the behavior expected of a person holding a certain status. Our roles in life have a great effect on our decisions and who we become.

Social Organization

In addition to structures, all societies have elements that are foundational to social life. Systems, culture, social facts, social networks, and socialization are important organizers of society.

Systems

Social systems are closely related to structure. Structure is the way in which parts of society are arranged. A system is a group of related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior. We can conceive of systems as physical entities that we can observe and examine (like a tree or a subway system) or as abstract constructs we can use to understand our world (like worldviews or relationships).

A system includes both individual parts and the relationships that hold the parts together—these can be physical flows (for example, the neural signals that allow us to sense our environment) or simply flows of information in a social system. Many parts can form a whole, but unless they depend on and interact with each other, they are simply a collection rather than a system.

Your body is a system composed of different, interacting, and interdependent organs or nested subsystems. A set of parts, arranged and connected, is essential for you to survive. These components can function together in ways that would not be possible for each part on its own. Just as your body’s connected organs work together to turn the food you eat into nutrients, all systems exhibit properties that emerge only when parts interact with a broader whole.

William Huitt presents a clear way to think about the systems model as it applies to human beings:

…consider the individual person as embedded first in the family then in the school and a circle of friends, and then in work or career. These are all embedded in one or more neighborhoods and a community which is, in turn, embedded in a region. These are, in turn, embedded in an international region and the world. The earth and solar system are part of the cosmos.

This conceptualization highlights the multiple relationships an individual has and the need to consider the specific relationships that might be important for a specific individual. What is common to all people, at least at this point in time, is that all are part of the cosmos and living on planet earth (Huitt 2012).

Many institutions are systems of organizations built from economic, political, and other spheres of activity (Walzer 1983). The economy is an institution, and capitalism is one kind of economic system that is made up of many forms of organizations, one of which is the multinational corporation.

Physicist and educator Fritjof Capra, PhD, is a forerunner in systems thinking and has dedicated his life to applying it to the development of sustainable communities. Watch the 1:43-minute video “Fritjof Capra Speaks to the Heart of the Matter” [Streaming Video] (figure 2.14) to learn about the systems perspective as a means for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. As you do, consider: What does Fritjof Capra say is crucial for building sustainable communities and solving global problems?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFtfrmmDxDk

In an increasingly complex world, thinking about sets of institutions as systems can help us understand how they are connected. For example, poverty, houselessness, unemployment, economic shifts, and climate change are all interrelated. Applying systems helps us to identify actions for some of our most challenging problems, such as overpopulation of the planet, terrorism, and global climate change (Saran 2020).

Culture

Culture, as we defined in Chapter 1, is the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a society or group. Over the past century, American and European sociologists have developed various definitions of culture (Sewell 1999). At the broadest level, you could think of culture as “different ways of seeing and doing things” (Wray 2014:xix). Cultural sociology, a specific subfield within sociology, focuses on meaning-making, particularly with symbols, categories, and interpretation.

We introduced cultural universals with snowball fights in Chapter 1. They are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. Gift-giving, bodily adornment, language, humor, and religion are all cultural universals. They also include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. However, each culture has its own ways of practicing traits differently.

For example, every human society recognizes a kind of family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions varies. In many cultures, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household (figure 2.15). In these cultures, young adults live in the extended family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household. Alternatively, they may remain and raise their family within the extended family’s homestead. In contrast, among many communities in the United States, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit that consists of parents and their offspring.

Cultural universals can also shift. For example, in some areas of the world, we are currently seeing a recognition of families that does not include reproduction or the care of children. They may be nonbinary couples, more than two adults living together as heads of a family, or cisgender couples who have decided not to have children.

Social Facts

Some sociologists study social facts—the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life. These practices exist outside of us as individuals, and they act to define our behavior. Social facts make it possible to move beyond studying individuals to learn about the behavior of entire societies. Social theorist Émile Durkheim asserted that social facts are concrete ideas that influence the daily life of individuals.

Durkheim discussed social facts within the context of kinship and marriage, language, and religion. One well-known example of Durkheim’s study of social facts is his examination of suicide rates. Using police suicide statistics from different districts, he found patterns in suicide rates that suggest suicide is not solely something that occurs at the level of the individual. He found that there is a very strong link between people taking their own lives and how they exist within social structures.

Durkheim proposed that suicide is related to our social integration: how well we know our place in society and how well we experience a sense of belonging. The mythical Greek story of Ajax can serve as a reminder that suicide has been a fact of life for societies at least as long as history can tell. Ajax took his own life during a deep period of humiliation after being passed over for promotion to lead the army by his fellow Greeks (figure 2.16).

Social Networks

A social network is the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. As Facebook and other social media sites show so clearly, social networks can be incredibly extensive. Social networks can be so large that an individual in a network may know little or nothing of another individual in the network (e.g., a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend). But these friends of friends can sometimes be an important source of practical advice and other kinds of help. They can open doors in the job market, introduce you to a potential romantic partner, or pass through some tickets to the next big basketball game.

Socialization

In addition to social facts and social networks, sociologists look at socialization as a foundational element of society. Let’s return for a moment to the elevator example that we discussed earlier in this chapter. We can say that through our interactions with others, we have been socialized to act in an elevator a certain way.

Socialization is the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction. We are socialized through interactions with our parents, friends, and other members of our social environment. Without socialization, we would not learn our culture, and without culture, we could not have a society. Socialization is an essential process for any society to be possible.

Socialization also affects how we identify. Think of the social influences that have informed how you identify, be it Latino or Hispanic, Filipino American or Central Asian, African, African American or Black, cisgender, transgender, male, female, queer, or heterosexual.

The Institution of Family

Let’s look closer at some of these parts of society through the institution of family. To better understand family in society, sociologists might ask: How do employment and economic conditions play a role in families’ experiences? How do people in the United States view marriage and family differently from those in other societies? With a social change lens, how do they view them differently over the years?

Consider the changes in U.S. families. The “typical” family in past decades consisted of married parents living in a home with their unmarried children. Today, the percentages of unmarried couples, same-sex couples, single-parent, and single-adult households are increasing, as well as the number of expanded households in which extended family members such as grandparents, cousins, or adult children live together in the family home. While 15 million mothers still make up the majority of single parents, 3.5 million fathers are also raising their children alone (U.S. Census Bureau 2020). Increasingly, single people and cohabiting couples are also choosing to raise children outside of marriage through surrogacy or adoption.

How do sociologists make sense of these changes? First, the pattern of humans’ family formation in most societies is considered a social fact. The expectations we have to form families are created by society, and this tends to govern our social lives. Even if we decide not to marry or have children, we are influenced by this pattern. Second, family is considered the most important of the agents of socialization, the significant individuals, groups, or institutions that influence our sense of self and the behaviors, norms, and values that help us function in society. That has prompted sociologists to devote significant attention to the study of the family as an institution. Third, as culture shapes all of society, it also shapes the practices, values, beliefs, symbols, language, and artifacts associated with family. Culture affects the way people behave in families, while families shape the larger culture of their communities.

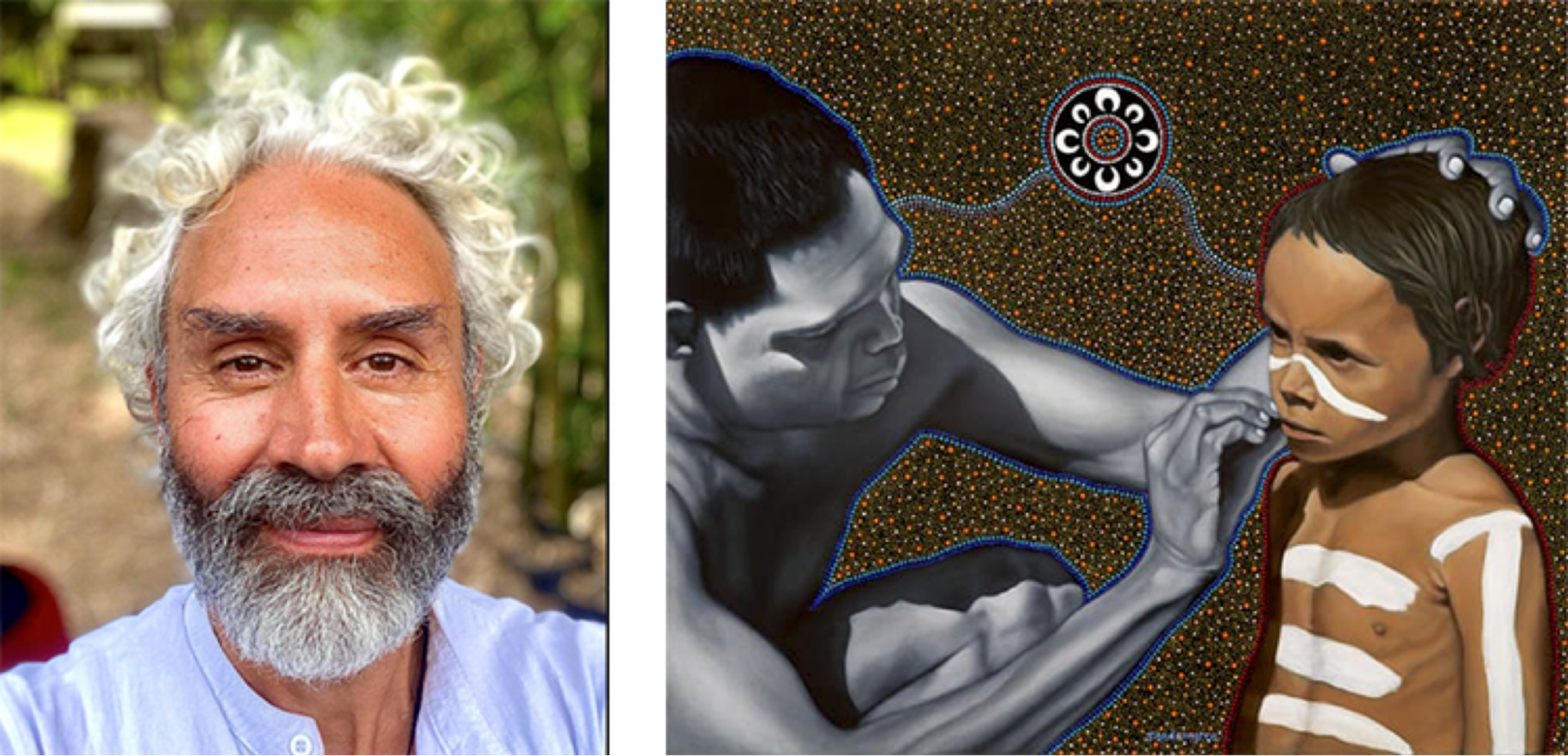

Let’s examine these concepts through a peek into Australian Aboriginal culture. For our inspiration, the artist Jandamarra Cad launched an exhibit in 2016 titled Kinship that explores the complex understandings of family in his culture. The exhibit included a painting titled Nourish and Uncle, which shows how connections are an integral component of wholeness to Aboriginals (figure 2.17).

Watch this 2:25-minute video, “What Is Meant by Kinship?” [Streaming Video] (figure 2.18), which describes how culture shapes the very complex structure of Aboriginal families in Australia. Do you see any difference between the kin structure that Colin Jones describes and the family structure that is familiar to you? What cultural practices, values, and beliefs do you see expressed in the kinship structure he describes?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kGnk9Tw8Sqk

For Australian Aboriginals, kinship refers to a system that determines how people relate to one another, responsibilities towards others, and marriage, ceremony, funeral roles, and behavior patterns. It also expresses a relationship to the natural world. Members are asked to adhere to kinship principles through their actions to create a cohesive and harmonious community.

Going Deeper

In 2018, the Scottish government applied a systems approach to determine how much progress had been made over the previous 10 years with their goals to serve the public. The goals of government officials were to:

- Create a more successful country.

- Give opportunities to all people living in Scotland.

- Increase the well-being of people living in Scotland.

- Create sustainable and inclusive growth.

- Reduce inequalities and give equal importance to economic, environmental, and social progress. (Scottish Government n.d.; OECD et al. 2020)

Find a visualization of their National Performance Framework on this page [Website]. How do you see systems thinking in the National Performance Framework?

To better understand Australian Aboriginal kinship, watch these videos: “Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Nations, Clans and Family Groups” [Streaming Video], “Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Skin Names” [Streaming Video], and “Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Moiety” [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for The Structure and Organization of Society

Open Content, Original

“The Structure and Organization of Society” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Structure of Society includes content from “Society and Social Interactions” in Diversity and Multi-Cultural Education in the 21st Century by Dr. Remi Alapo, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, “5.1 Social Structure: The Building Blocks of Social Life” in Sociology; Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, and “Conceptualizing Structures of Power” by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken, in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications made for clarity in the context of this text. The Prezi (figure 2.11) and videos (figures 2.12 and 2.13) along with their associated content added.

Figure 2.10. “Social Structure” by Shane is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 2.15. “Mongolian Family Members” on Flickr by Bernd Thaller is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“Social Facts” is adapted from “Social Facts” in “What is Sociology?” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, addition of image and Greek story of Ajax.

“Social Networks” is adapted from “Social Networks” in “5.1 Social Structure: The Building Blocks of Social Life” in Sociology; Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Very minor edits.

Figure 2.16. “Aithiopis XII – Ajax Suicide by Exekias” on Flickr by Egisto Sani is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The second and third paragraphs of “The Institution of Family” include content adapted from “1.1 What is Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang. Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, agents of socialization added.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.11. “Social Institutions” by Elizabeth Berrios is included under fair use.

Figure 2.12. “The Family Equation” by StoryCorps is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.13. “My Aunties: Father Figures” by StoryCorps is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.14. “Fritjof Capra Speaks to the Heart of the Matter” by Films for Change is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.17. Image of Artist Jandamarra Cad is found on Instagram (left). Nourish and Uncle is found at “Jandamarra Cadd – Master Artist – Bridging the Divide” (right). Both images are used with permission of the artist.

Figure 2.18. “What Is Meant by Kinship?” by Rural Medical Education Australia is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life.

the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the rank, honor, or prestige attached to one’s position in society or a group.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

the significant individuals, groups, or institutions that influence our sense of self and the behaviors, norms, and values that help us function in society.