1.4 How Western Science Views the Environment

So how does western science view the environment, and humanity’s relationship to it? In fact there are probably as many different answers to that question as there are scientists. And those values and ethics have changed dramatically over time, both as the culture around us has changed and also as we’ve gained greater and deeper understandings of how human systems and natural systems work, and how they interact.

It is undeniable that humans are dramatically impacting the environment. Of the different forms of life that have inhabited the Earth in its three to four billion year history, 99.9% are now extinct. Against this backdrop, the human enterprise with its roughly 200,000-year history barely merits attention. As the American novelist Mark Twain once remarked, if our planet’s history were to be compared to the Eiffel Tower, human history would be a mere smear on the very tip of the tower. But while modern humans (Homo sapiens) might be insignificant in geologic time, we are by no means insignificant in terms of our recent planetary impact. A 1986 study estimated that 40% of the product of terrestrial plant photosynthesis — the basis of the food chain for most animal and bird life — was being appropriated by humans for their use. More recent studies estimate that 25% of photosynthesis on continental shelves (coastal areas) is ultimately being used to satisfy human demand. Human appropriation of such natural resources is having a profound impact upon the wide diversity of other species that also depend on them.

Evolution normally results in the generation of new lifeforms at a rate that outstrips the extinction of other species; this results in strong biological diversity. However, scientists have evidence that, for the first observable time in evolutionary history, another species — Homo sapiens — has upset this balance to the degree that the rate of species extinction is now estimated at 10,000 times the rate of species renewal. Human beings, just one species among millions, are crowding out the other species we share the planet with. Evidence of human interference with the natural world is visible in practically every ecosystem from the presence of pollutants in the stratosphere to the artificially changed courses of the majority of river systems on the planet. It is argued that ever since we abandoned nomadic, gatherer-hunter ways of life for settled societies some 12,000 years ago, humans have continually manipulated their natural world to meet their needs. While this observation is a correct one, the rate, scale, and the nature of human-induced global change — particularly in the post-industrial period — is unprecedented in the history of life on Earth.

There are three primary reasons for this:

Firstly, mechanization of both industry and agriculture in the last century resulted in vastly improved labor productivity which enabled the creation of goods and services. Since then, scientific advance and technological innovation — powered by ever-increasing inputs of fossil fuels and their derivatives — have revolutionized every industry and created many new ones. The subsequent development of western consumer culture, and the satisfaction of the accompanying disposable mentality, has generated material flows of an unprecedented scale. A recent study calculated that humans are now responsible for moving greater amounts of matter across the planet than all natural occurrences (earthquakes, storms, etc.) put together.

Secondly, the sheer size of the human population is unprecedented. Every passing year adds another 90 million people to the planet. Even though the environmental impact varies significantly between countries (and within them), the exponential growth in human numbers, coupled with rising material expectations in a world of limited resources, has catapulted the issue of distribution to prominence. Global inequalities in resource consumption and purchasing power mark the clearest dividing line between the haves and the have-nots. It has become apparent that present patterns of production and consumption are unsustainable for a global population that is projected to reach between 12 billion by the year 2050. If ecological crises and rising social conflict are to be countered, the present rates of overconsumption by a rich minority, and under-consumption by a large majority, will have to be brought into balance.

Thirdly, it is not only the rate and the scale of change but the nature of that change that is unprecedented. Human inventiveness has introduced chemicals and materials into the environment which either do not occur naturally at all, or do not occur in the ratios in which we have introduced them. These persistent chemical pollutants are believed to be causing alterations in the environment, the effects of which are only slowly manifesting themselves, and the full scale of which is beyond calculation. CFCs and PCBs are but two examples of the approximately 100,000 chemicals currently in global circulation. (Between 500 and 1,000 new chemicals are being added to this list annually.) The majority of these chemicals have not been tested for their toxicity on humans and other life forms, let alone tested for their effects in combination with other chemicals. These issues are now the subject of special UN and other intergovernmental working groups.

Frontier Ethic

The ways in which humans interact with the land and its natural resources are determined by ethical attitudes and behaviors. Early European settlers in North America rapidly consumed the natural resources of the land. After they depleted one area, they moved westward to new frontiers. Their attitude towards the land was that of a frontier ethic. A frontier ethic assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere or alternatively human ingenuity will find substitutes. This attitude sees humans as masters who manage the planet. The frontier ethic is completely anthropocentric (human-centered), for only the needs of humans are considered.

Most industrialized societies experience population and economic growth that are based upon this frontier ethic, assuming that infinite resources exist to support continued growth indefinitely. In fact, economic growth is considered a measure of how well a society is doing. The late economist Julian Simon pointed out that life on earth has never been better, and that population growth means more creative minds to solve future problems and give us an even better standard of living. However, now that the human population has passed seven billion and few frontiers are left, many are beginning to question the frontier ethic. Such people are moving toward an environmental ethic, which includes humans as part of the natural community rather than managers of it. Such an ethic places limits on human activities (e.g., uncontrolled resource use), that may adversely affect the natural community.

Some of those still subscribing to the frontier ethic suggest that outer space may be the new frontier. If we run out of resources (or space) on earth, they argue, we can simply populate other planets. This seems an unlikely solution, as even the most aggressive colonization plan would be incapable of transferring people to extraterrestrial colonies at a significant rate. Natural population growth on earth would outpace the colonization effort. A more likely scenario would be that space could provide the resources (e.g. from asteroid mining) that might help to sustain human existence on earth.

Sustainability

A sustainable ethic, in contrast, is an environmental ethic by which people treat the earth as if its resources are limited. The concept of sustainability refers to the sociopolitical, scientific, and cultural challenges of living within the means of the earth without significantly impairing its function. Our Common Future (1987), the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, is widely credited with having popularized the concept of sustainable development. It defines sustainable development in the following ways…

- …development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- … sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the orientation of the technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs.

The concept of sustainability, however, can be traced back much farther to the oral histories of indigenous cultures. For example, the principle of inter-generational equity is captured in the Inuit saying, ‘we do not inherit the Earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children’. The Native American ‘Law of the Seventh Generation’ is another illustration. According to this, before any major action was to be undertaken its potential consequences on the seventh generation had to be considered. As a species we are at present only about 6,000 generations old. In the US, our current political decision-makers operate on time scales of months or few years at most, the thought that other human cultures have based their decision-making systems on time scales of many decades seems wise, but unfortunately inconceivable in the current political climate.

A sustainable ethic assumes that the earth’s resources are not unlimited and that humans must use and conserve resources in a manner that allows their continued use in the future. A sustainable ethic also assumes that humans are a part of the natural environment and that we suffer when the health of a natural ecosystem is impaired. A sustainable ethic includes the following tenets:

- The earth has a limited supply of resources.

- Humans must conserve resources.

- Humans share the earth’s resources with other living things.

- Growth is not sustainable.

- Humans are a part of nature.

- Humans are affected by natural laws.

- Humans succeed best when they maintain the integrity of natural processes sand cooperate with nature.

For example, if a fuel shortage occurs, how can the problem be solved in a way that is consistent with a sustainable ethic? The solutions might include finding new ways to conserve oil or developing renewable energy alternatives. A sustainable ethic attitude in the face of such a problem would be that if drilling for oil damages the ecosystem, then that damage will affect the human population as well. A sustainable ethic can be either anthropocentric or biocentric (life-centered). An advocate for conserving oil resources may consider all oil resources as the property of humans. Using oil resources wisely so that future generations have access to them is an attitude consistent with an anthropocentric ethic. Using resources wisely to prevent ecological damage is in accord with a biocentric ethic.

Land Ethic

Aldo Leopold, an American wildlife natural historian and philosopher, advocated a biocentric ethic in his book, A Sand County Almanac. He suggested that humans had always considered land as property, just as ancient Greeks considered slaves as property. He believed that mistreatment of land (or of slaves) makes little economic or moral sense, much as today the concept of slavery is considered immoral. All humans are merely one component of an ethical framework. Leopold suggested that land be included in an ethical framework, calling this the land ethic.

“The land ethic simply enlarges the boundary of the community to include soils, waters, plants and animals; or collectively, the land. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow members, and also respect for the community as such.” (Aldo Leopold, 1949)

Leopold divided conservationists into two groups: one group that regards the soil as a commodity and the other that regards the land as biota, with a broad interpretation of its function. If we apply this idea to the field of forestry, the first group of conservationists would grow trees like cabbages, while the second group would strive to maintain a natural ecosystem. Leopold maintained that the conservation movement must be based upon more than just economic necessity. Species with no discernible economic value to humans may be an integral part of a functioning ecosystem. The land ethic respects all parts of the natural world regardless of their utility, and decisions based upon that ethic result in more stable biological communities.

Environmental equity

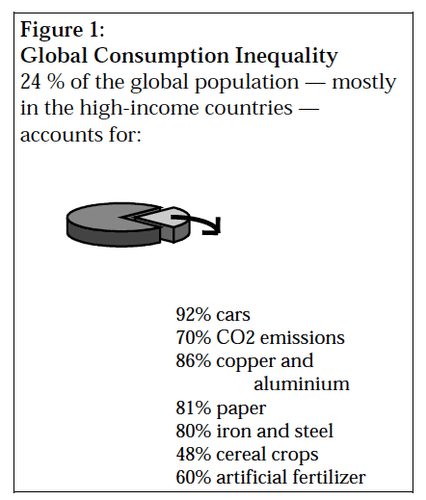

While much progress is being made to improve resource efficiency, far less progress has been made to improve resource distribution. Currently, just one-fifth of the global population is consuming three quarters of the earth’s resources (Figure 1). If the remaining four-fifths were to exercise their right to grow to the level of the rich minority it would result in ecological devastation. So far, global income inequalities and lack of purchasing power have prevented poorer countries from reaching the standard of living (and also resource consumption/waste emission) of the industrialized countries.

Countries such as China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia are, however, catching up fast. In such a situation, global consumption of resources and energy needs to be drastically reduced to a point where it can be repeated by future generations. But who will do the reducing? Poorer nations want to produce and consume more. Yet so do richer countries: their economies demand ever greater consumption-based expansion. Such stalemates have prevented any meaningful progress towards equitable and sustainable resource distribution at the international level. These issue of fairness and distributional justice remain unresolved.

The Precautionary Principle

The precautionary principle is an important concept in environmental sustainability. A 1998 consensus statement characterized the precautionary principle this way: “when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically”. For example, if a new pesticide chemical is created, the precautionary principle would dictate that we presume, for the sake of safety, that the chemical may have potential negative consequences for the environment and/or human health, even if such consequences have not been proven yet. In other words, it is best to proceed cautiously in the face of incomplete knowledge about something’s potential harm.

Environmental History: Hethch Hetchy Valley

In 1913, the Hetch Hetchy Valley – located in Yosemite National Park in California – was the site of a conflict between two factions, one with an anthropocentric ethic and the other, a biocentric ethic. As the last American frontiers were settled, the rate of forest destruction started to concern the public.

The conservation movement gained momentum, but quickly broke into two factions. One faction, led by Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester under Teddy Roosevelt, advocated utilitarian conservation (i.e., conservation of resources for the good of the public). The other faction, led by John Muir, advocated preservation of forests and other wilderness for their inherent value. Both groups rejected the first tenet of frontier ethics, the assumption that resources are limitless. However, the conservationists agreed with the rest of the tenets of frontier ethics, while the preservationists agreed with the tenets of the sustainable ethic.

The Hetch Hetchy Valley was part of a protected National Park, but after the devastating fires of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, residents of San Francisco wanted to dam the valley to provide their city with a stable supply of water. Gifford Pinchot favored the dam.

“As to my attitude regarding the proposed use of Hetch Hetchy by the city of San Francisco…I am fully persuaded that… the injury…by substituting a lake for the present swampy floor of the valley…is altogether unimportant compared with the benefits to be derived from it’s use as a reservoir. The fundamental principle of the whole conservation policy is that of use, to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people.” (Gifford Pinchot, 1913)

John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club and a great lover of wilderness, led the fight against the dam. He saw wilderness as having an intrinsic value, separate from its utilitarian value to people. He advocated preservation of wild places for their inherent beauty and for the sake of the creatures that live there. The issue aroused the American public, who were becoming increasingly alarmed at the growth of cities and the destruction of the landscape for the sake of commercial enterprises. Key senators received thousands of letters of protest.

“These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the Mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar.” (John Muir, 1912)

Despite public protest, Congress voted to dam the valley. The preservationists lost the fight for the Hetch Hetchy Valley, but their questioning of traditional American values had some lasting effects. In 1916, Congress passed the “National Park System Organic Act,” which declared that parks were to be maintained in a manner that left them unimpaired for future generations. As we use our public lands, we continue to debate whether we should be guided by preservationism or conservationism.

Suggested Supplementary Reading: Blankenbuehler, P. 2016. Why Hetch Hetchy is staying under water. High Country News. <https://www.hcn.org/issues/48.9/why-hetch-hetchy-is-staying-under-water>

Attribution

Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from the original by A. Geddes, Matthew R. Fisher.