1.5 Environmental Justice & Indigenous Struggles

Environmental Justice

Environmental Justice is defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. With this definition in mind, environmental justice has yet to be actualized.

The world we currently live in is shaped by economic, political, and social values that have been prioritized and imposed by primarily Western countries, such as the United States, England, Spain, and other countries in Western Europe, onto the rest of the world. Colonization, which can be defined as the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous people of an area, has been a fundamental method for Western countries to establish these values across continents. Colonization is an ongoing process that has subsequently created or emphasized biases, such as environmental racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia. All of these intersect with climate-related and resource-use issues.

The economic, political, and social systems that environmental science lives within are based on exponential growth and individualism. In the United States, we see the devastating consequences of climate change- from extreme wildfires in the west to deadly hurricanes in the east, to the health crisis of COVID-19. These repercussions are not coincidental, they are because of our use and exploitation of natural resources. The use and benefits of these resources are unequally distributed. And while all of us will experience the aftermath of climate change, not all people will experience it equally. People of color, especially Black and Indigenous people, and other marginalized individuals and communities are often on the frontlines of climate change and experience the highest intensity of its effects.

What does environmental justice look like when it is put into practice? In every sphere, the answer can be different. Regardless of where we are or what systems we are working within, we can search for solutions that center both human and ecosystem well-being.

Indigenous Struggle and Knowledge

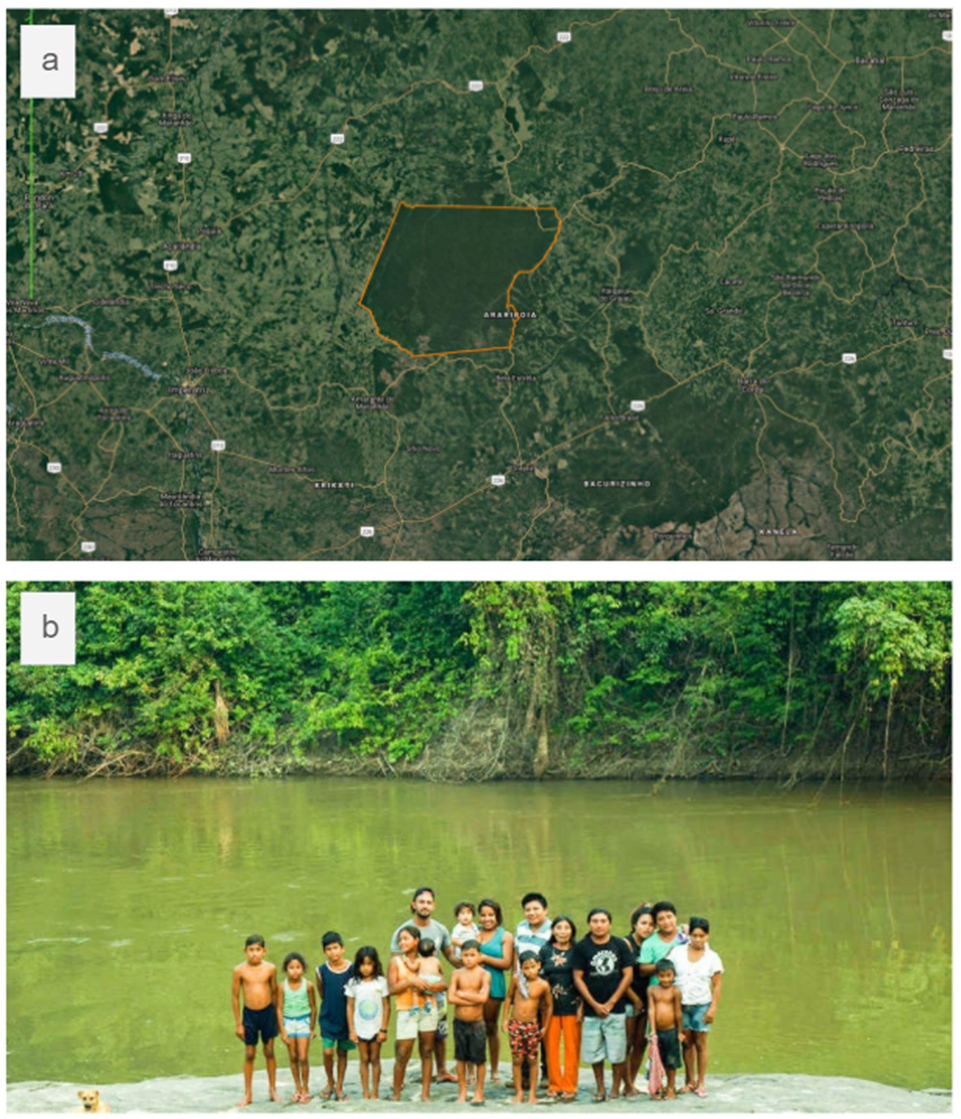

Central to actualizing environmental justice, and to deepening our understanding of environmental systems, is recognizing and supporting the many ongoing Indigenous struggles that exist today. As a result of colonization, Indigenous people make up only five percent of the population worldwide but manage and support 80 percent of global biodiversity. While the traditions, languages, and beliefs of Indigenous people vary tremendously across the world, this statistic points to a common value that is seen in Indigenous cultures: the emphasis on protecting and stewarding of their environments. Many Indigenous cultures have intimate connections to the land, water, and ecosystems that they have a relationship to. This leads to a deep understanding of their environment and their own impacts on the systems that they rely on. It also leads to the cultural value of sustainability. The cultures who practice this believe that taking care of and managing these resources will allow future generations to live in prosperity and preserve their cultures and traditions.

Currently, our economic, political, and social systems in Western-dominated countries do not share or reflect these values. This is one of the major contributing factors that has led to intense environmental degradation on small and large scales. Indigenous struggles that exist today reflect and address the underlying problems within Western-dominated societies, such as the United States. Some examples of these struggles include, but are not limited to:

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

- Deforestation

- Water protection

- Anti-fossil fuel extraction

- Food sovereignty

- Language revitalization

- Land rematriation

While not all Indigenous people fight for or align with these issues, all of these issues apply to the practice of environmental justice. For centuries, most Indigenous people across the world have been stewarding the land of their ancestors while simultaneously creating complicated and developed cultures, civilizations, and traditions. These societies and ways of life coexisted and continue to coexist with the natural world around them.

For these reasons, the project of environmental science, of understanding complex environmental systems and their interactions with our own human systems, is currently seen by some people as inextricably linked to environmental equality, and specifically to the survival and leadership of indigenous communities. And if we wish to live in a world that is environmentally just, then we must center the struggles and knowledge of Indigenous peoples.

Attribution: by Avery Temple, licensed under CC BY 4.0.