6.2 Ecosystem Services

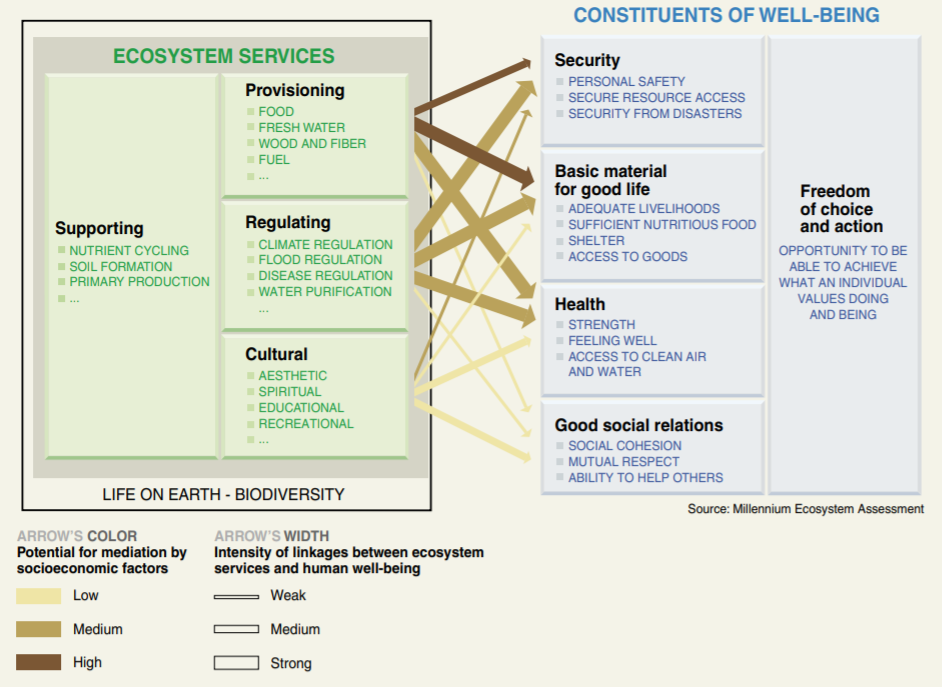

Healthy ecosystems are ecological life-support systems for every living thing on Earth, including humans. They provide a full suite of goods and services that are vital to human health and livelihood, natural assets we call ecosystem services. Figure 1

Many of these goods and services are traditionally viewed as free benefits to society, or “public goods” – wildlife habitat and diversity, watershed services, carbon storage, and scenic landscapes, for example. Lacking a formal market, these natural assets are traditionally absent from society’s balance sheet; their critical contributions are often overlooked in public, corporate, and individual decision-making.

When our forests, deserts, wetlands, and other biomes are undervalued, they are increasingly susceptible to development pressures and conversion, to pollution and other human waste, or to other types of degradation. Recognizing ecosystems as natural assets with economic and social value can help promote conservation and more responsible decision-making.

Ecosystem Services are commonly defined as benefits people obtain from ecosystems. These services can be categorized as:

- Provisioning Services or the provision of food, fresh water, fuel, fiber, and other goods;

- Regulating Services such as climate, water, and disease regulation as well as pollination;

- Supporting Services such as soil formation and nutrient cycling; and

- Cultural Services such as educational, aesthetic, and cultural heritage values as well as recreation and tourism.

As population, income, and consumption levels increase, humans put more and more pressure on the natural environment to deliver these benefits. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment – a four-year United Nations assessment of the condition and trends of the world’s ecosystems conducted by over 1300 international experts – found that 60% of ecosystem services assessed globally are either degraded or being used unsustainably. Seventy percent of the regulating and cultural services evaluated in the assessment are in decline. Those scientists predicted that ecosystem degradation could grow significantly worse in the first half of the 21st century, with important consequences to human well-being.

Climate change, pollution, over-exploitation, and land-use change are some of the drivers of ecosystem loss, as well as resource challenges associated with globalization and urbanization. Land use change is an immediate issue. In the United States we are losing open space, and seeing a decline in forest health and biodiversity, particularly on private lands. Approximately 57% of all forestland in the United States, or 429 million acres, is privately owned. Recent trends in parcelization and divestiture of private lands in the United States suggest that private landowners are commonly under economic pressures to sell their forest holdings. Rising property values, tax burdens, and global market competition are some of the factors that motivate landowners to sell their lands, often for development uses. The loss of healthy forests directly affects forest landowners, rural communities, and the economy. As private lands are developed, we also lose the life-supporting ecosystem services that forests provide.

Regulations, land acquisitions, conservation easements, and tax incentives are some of the conservation approaches that aim to protect and conserve the Nation’s forests, grasslands, and other intact ecosystems. Over the past decade, advances in sustainable forest management and forest certification have complemented conservation objectives. Traditional conservation programs, however, may not be enough to safeguard natural landscapes and biodiversity, and traditional markets may not provide landowners with a sufficient economic incentive to own and sustainably manage forestland. To reverse the loss and degradation of ecosystem services, economic and financial motivations must include a conservation objective, and the value of ecosystem services needs to be incorporated into any decision-making.

Carbon Sequestration

Interest in terrestrial carbon sequestration has increased in an effort to explore opportunities for climate change mitigation. Carbon sequestration is the process by which atmospheric carbon dioxide is taken up by trees, grasses, and other plants through photosynthesis and stored as carbon in biomass (trunks, branches, foliage, and roots) and soils. The sink of carbon sequestration in forests and wood products helps to offset sources of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, such as deforestation, forest fires, and fossil fuel emissions.

Sustainable forestry practices can increase the ability of forests to sequester atmospheric carbon while enhancing other ecosystem services, such as improved soil and water quality. Planting new trees and improving forest health through thinning and prescribed burning are some of the ways to increase forest carbon in the long run.

In response to government, business, and individual commitments to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, carbon is now a priced environmental commodity in the global marketplace. The United States carbon market is in its formative stages. States and regions are developing climate change strategies and policy for reducing carbon dioxide emissions, and mandatory markets are forming at the regional and state levels. The Voluntary Reporting of Greenhouse Gases Program, established by Section 1605(b) of the Energy Policy Act of 1992, provides a means for organizations and individuals – including forest landowners and other land managers – to record their baseline emissions and emission reductions.

Check your understanding

Which of the four categories of ecosystem service includes carbon sequestration?

Watershed Services

A watershed is all of the land which channels water into a particular stream, or past a particular point. Figure 2 Healthy forests, wetlands, or other natural systems provide a host of watershed services to everyone downstream, including water purification, ground water and surface flow regulation, erosion control, and streambank stabilization. The importance of these watershed services will only increase as water quality becomes a critical issue around the globe. Their financial value becomes particularly apparent when the costs of protecting an ecosystem for improved water quality are compared with investments in new or improved infrastructure, such as purification plants and flood control structures. It is almost always cheaper and more efficient to invest in ecosystem management and protection, rather than trying to reproduce those ecosystem services through use of human systems.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity and it’s benefits were covered in depth in chapter 5. Payments to private landowners for conserving biodiversity often come from nongovernmental organizations that have biodiversity objectives. Other interests include the ecotourism and pharmaceutical industries, whose payments secure access to biodiversity hotspots. The development of market-based instruments is challenging and nebulous, largely due to a lack of buyers and financial investment as well as the difficulty in defining biodiversity units of measure. In some cases regulatory frameworks have mobilized market transactions; the emergence of conservation banking in the US, for example, may give private landowners a new incentive to manage forests and conserve critical habitat.

Neighborhood Trees

Healthy trees are valuable assets for communities. Urban and community forests contribute to energy savings, better air and water quality, reduced storm water runoff, carbon storage, and increased property values. Street trees and parks moderate local climate and provide aesthetic and recreational values to communities. There are generally far more trees in wealthier areas than in poorer neighborhoods.

As natural elements of a built landscape, trees improve urban life and are critical to human health and emotional well-being. Research suggests that human beings have an innate affiliation to natural settings – a concept described as biophilia. Numerous studies link access to natural light, outdoor air, and living trees to increased employee and student productivity, faster hospital recoveries, less crime, and an overall reduction in stress and anxiety.

In an effort to maintain and improve the public benefits of trees, more and more cities throughout the United States are setting tree canopy goals. Community forests are becoming incorporated in sustainable growth strategies that seek to provide elements of green space – parks, gardens, farmlands, and other open areas. Investments in protected “green infrastructure” – strategically planned and locally managed networks of open green space – connect people to nature and to each other, providing a higher quality of life for community residents.

Attribution

USFS Ecosystem services, More About Ecosystem Services, Carbon Sequestration, Watershed Services, Biodiversity, Neighborhood Trees, modified from the original by A Geddes