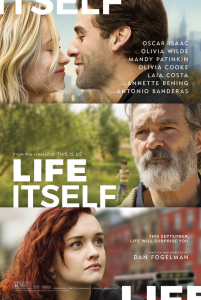

86 Life Itself (2018)

There is Still Love to be Found

By Kyler Jones

Life Itself is an emotional film that explores the concept of the unreliable narrator through the intertwining tales of two families on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Through differences in culture, class, and circumstances, we see how these two families go through separate struggles but end up in the same place. The movie uses character-centered chapters to explain its overarching story. Each chapter focuses on an individual or a group of individuals, explaining their personal backstories and connecting them to the story as a whole. The takeaway of the story is intended to be one of love; In the most difficult trials life forces on us, there is still love to be found. The moral of the story is to find and cherish that love during life’s struggles.

Trying to effectively convey such a sentimental message in less than two hours is quite the task to take on. The success that the film achieves in this endeavor is debatable, at least according to film critics. Freelance writer Monica Castillo explains that the film left her emotionally jarred as it lept back and forth between the emotional highs and lows. Castillo provides an example of this in describing the story’s abrupt shift from heartbreaking events in New York City to an easy-going, quiet town in Andalusia, Spain. This seemingly unnecessary back-and-forth is a common thread for critic complaints of the film; However, I would argue that this emotional merry-go-round is intentional. Within 5 minutes, this movie mentions the unreliable narrator, but it isn’t until about 30 minutes into the film that the viewer is told (indirectly) how the unreliable narrator will fit into this story.

This film uses cinematography, editing, and sound design very effectively to contribute to the depth of the film. There is a scene where the viewer receives an explanation of Life Itself’s narrative direction from Abby, a character that we only see in flashbacks. In this scene, Abby barges into the fraternity house of her boyfriend, Will, to discuss an idea for her thesis. Will and his frat brothers are smoking weed and working their way through a keg of beer; a shaky camera focuses on Abby while she frantically tells her idea. There is an establishing shot that shows the confusion of the group of men as Abby begins her description. The piano in the background begins to add to the buildup of the explanation; more instruments join to emphasize the director’s approach to defining this philosophical idea of life itself being an unreliable narrator. The camera focuses on Abby almost the entire time as she paces around, only changing the shot to show the lack of understanding on Will’s face. Then, Abby explains that life, being full of twists and turns, is just like the unreliable narrator used in storytelling. Life is the ultimate unreliable narrator, only showing us part of the story.

Life Itself is not the first to entertain the idea that an unreliable narrator exists outside of fiction. English Philology Professor Vera Nünning writes that unreliable narrators can be found everywhere (1). Originally introduced as a concept in 1961 by scholar Wayne C. Booth, the unreliable narrator is used to deceive the reader in an attempt to surprise them with a twist (Nünning, 6). Put simply, it is meant to divert the reader’s expectations. In the film, the character Abby argues that life diverts our expectations constantly. So, it stands to reason that a movie that explores this concept would have multiple twists and turns, leading to the “emotional whiplash” that writer Castillo mentions in her criticism. That “emotional whiplash” is intentional.

The story of Life Itself came about when writer and director Dan Fogelman was listening to “Time Out of Mind” by Bob Dylan and thought about the ways that his life had changed since his mother’s passing (Kaufman). Bob Dylan’s album is important to note as it is an integral part of the storytelling and sound design of this movie. There is a particular emphasis on the song “Make You Feel My Love” as it is revised several times throughout the film to accompany moments of romantic or paternal love. In pondering on the death of his mother, his relationship with his wife, and his successful career, Fogelman unintentionally encoded a fictionalized version of the ups and downs of his own life into this film (Kaufman). Fogelman discusses this more in depth during his interview, where he mentions realizing that this film was a representation of the women in his life. Similarly, the character of Will also expresses subconscious interests during his scenes.

The film does a nice job using its tools to effectively direct the viewer’s attention to important details. Towards the beginning of the first chapter, an intoxicated and medicated Will is obnoxiously singing a Bob Dylan song inside of a coffee shop. In the following scene, Will reminisces about Abby’s obsession with Dylan’s album “Time Out of Mind” while another song from that album carries us into the view of Will walking down a busy street. The editing takes us back and forth through Will’s past memory and his present-day stroll through the city. The camera almost exclusively focuses on Will, only shifting focus whenever Will himself focuses on something in the city. This helps the viewer to see his point of view. He notices a bus, a baby stroller, and a dog, the dog and stroller connecting with the memory he’s reminiscing about. The focus on the bus seems almost out of place until later in the film, when we learn about Abby being hit by a bus. In repeat viewings, it is easy to decode the writing on the wall that this scene provides.

The third chapter of Life Itself has the aforementioned jump to Spain that seemingly comes out of nowhere. This chapter shows the most range when it comes to the issues of difference, power, and discrimination. The film doesn’t focus on these issues directly, but this chapter shows a few different ways that hegemony can affect people, one of these ways being the cultural differences seen in Mr. Saccione’s description of his youth. His father was an Italian man who, upon visiting Spain, found a beautiful woman that he would marry and take back home with him to Italy. That woman was Mr. Saccione’s mother, and the two of them were discriminated against while living in Italy, primarily by his father who was disgusted that he didn’t end up with an “Italian” family. This upbringing leads Mr. Saccione to form a disliking for Italy and a rebellious pride for Spain. Life Itself shows how cultural discrimination influenced this character’s life and motivated his actions (the purchase of land in Spain), but his actions are not defined by his discrimination. The discriminatory actions of his father are vilified, but Mr. Saccione’s character has much more depth beyond the discrimination that he suffered.

Something else that this chapter shows is the remnants of a patriarchal system being in play. Mr. Saccione and Javier have competing egos and seem to be battling for the attention of Bella. There almost seems to be this idea that Bella is a prize that the two indirectly compete for. In contrast to these assertive men, Bella is a more subtle example of strength; she simply wants what is best for herself and her family. Her consistent presence as more than just “Javier’s wife” shows her strength. She is strong because she maintains her own goals, independent of the two men battling for a place in her life. It is that independent drive and steadfastness that makes her a strong female character (Masterclass). Her independence is seen most clearly when she lets Javier leave after reassuring him that he was never her savior and that she chose him because she saw his potential and knew that she deserved someone good for herself. Despite the toxic masculinity on display between Javier and Mr. Saccione, she maintains her level-headed commitment to herself and to her son’s well-being.

Finally, we see the struggles of capitalism and class felt by Javier and Bella. When their son experiences a traumatic event, they take him to several doctors to try and rehabilitate his mental health. Unfortunately, their son’s health does not improve but Javier insists he just needs more time. Bella stops Javier and says they need the doctors that the rich people use. Javier stresses that they are not rich people, but Bella persists because it is in her son’s best interest. This leads to them seeking the financial support of Mr. Saccione, which ultimately leads to the end of their relationship. Accepting Mr. Saccione’s help -that help being of someone from another class- results in Javier feeling that he isn’t best for Bella.

This movie was faulted by critics for trying to fit too much emotional impact into one film. Director Fogelman explained that perhaps the negative reviews were because many of the critics were emotionally averse white men (Sippell). Perhaps patriarchy and capitalism were even influencing the reception of the film. Critic Margeaux Sippell quickly refutes this in her article though, explaining that reviews written by women also gave it negative ratings. Despite such negative reception from critics, audience scores have left the film with an 83% on Rotten Tomatoes (a sharp contrast from the 13% given by the site’s critics). Maybe for director Fogelman, life’s twists and turns were the unexpected criticisms, but the love to be found was in the audience reception of the film. With all of this, it might seem hard to determine whether Life Itself should be considered a good film. The acting, cinematography, sound design, and editing of Life Itself have all been praised, yet it remains a very divisive movie. With a good understanding of the depth that the film is trying to accomplish, however, I believe that this is an exceptional movie.

REFERENCES

Castillo, Monica. “Life Itself Movie Review & Film Summary (2018).” Movie Review & Film Summary (2018) | Roger Ebert, RogerEbert, 21 Sept. 2018, www.rogerebert.com/reviews/life-itself-2018.

Kaufman, Amy. “’This Is Us’ Creator Dan Fogelman Reacts to the Dismal ‘Life Itself’ Reviews and Says He’s Not Weepy.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 22 Sept. 2018, www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-life-itself-dan-fogelman-20180922-story.html.

MasterClass. “How to Write Strong Female Characters – 2021.” MasterClass, MasterClass, 23 Aug. 2021, www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-write-strong-female-characters#4-characteristics-of-strong-female-characters.

Nünning, Vera. “Unreliable Narration and Trustworthiness : Intermedial and Interdisciplinary Perspectives” edited by Vera Nünning, De Gruyter, Inc., 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, 1-6. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/linnbenton-ebooks/detail.action?docID=2028738.

Rotten Tomatoes. “Life Itself.” Rotten Tomatoes, www.rottentomatoes.com/m/life_itself_2018.

Sippell, Margeaux. “Dan Fogelman Defends ‘Life Itself’ Against Hilariously Bad Reviews.” Variety, Variety, 20 Sept. 2018, variety.com/2018/film/news/life-itself-reviews-dan-fogelman-what-critics-saying-1202951049/.