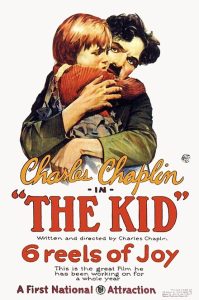

1 The Kid (1921)

Gender and Class in The Kid (1921)

by Hannah Wells

“Romance fails and so do friendships, but the relationship of parent and child remains indelible and indestructible, the strongest relationship on earth” – Theodor Reik. This quote perfectly sums up the foundation of the silent film The Kid (1921) by Charlie Chaplin. This movie beautifully articulates the loving bond between a child and their parents, whether biological or not. It focuses on the tramp, Charlie Chaplin, as he takes care of an orphaned child named John who was abandoned by his mother due to her feeling incapable of taking care of him. Throughout the movie, we see the tramp coming to terms with his attachment to John, and the mother realizing she can and wants to take care of the baby that she abandoned. As I mentioned above, this film makes a powerful commentary on the sacrificial and sometimes unexpected bond between a parent and child through its visual and audio techniques. Specifically, the film explores the roles expected of a woman and a man through these gender roles and a relevant commentary on the upper and lower classes.

The Kid was was relevant to Chaplin in a very special way, as his wife of the time “became pregnant and gave birth to a malformed boy, who died after only three days” (Filming The Kid). Although it is never specifically stated that this film was a response to that moment, the emotions and parental-child commentary hint that it may have been at the very least an inspiration and drive for it. In a more historical light, WWI had just ended two years earlier, creating financial disparities as well as feelings of sadness and mourning for those who had lost their own children in the war or those who had maybe lost their parents.

With that let’s jump into the important parental and child relationships in The Kid, starting with the mother. Through her, we see this side of the sacrificial relationship between a parent and a child, in the film, there’s a scene that makes a direct commentary on this. In this scene, we see the mother, established in a long shot leaving a hospital with her baby and looking around seemingly confused and feeling helpless. It then dissolves into a still image of Jesus Christ carrying the cross. This comparison shows the grief and sorrow a mother that knows she cannot care for her child carries. The suffering comes in the way of the mother giving up her child for something she perceives as better, making the connection with Christ of suffering for the greater good of another. I believe this is also a commentary on the unwillingness of the father to care for his child, as we see the father in the film for a small scene. It alludes to the fact that he has an art career and has a moment where he stares at the mother’s picture with some sort of longing but eventually burns it. This shows the discrimination between a man and woman in a relationship when it comes to a child. The father can quite easily disappear during a woman’s pregnancy and never return, burning all ties and never dealing with the fallout. Meanwhile, the woman would, whether financially able or not, carry the baby to term and must raise the baby. Along with occasionally being ostracized from society for raising a baby alone.

The other parental, child relationship we have is between the tramp and John. This relationship is more complicated as throughout the beginning of the movie the relationship seems more transactional. They make a living together by John breaking people’s windows and the tramp conveniently walking by with a fresh window and some putty to help. Consequently getting paid for the services, and helps pay for food. What really makes this relationship seem like more of an attempt toward a transactional, non-emotional one is early on in the movie. We see John making pancakes by himself for the both of them, while the tramp sits and reads the paper in his bed. Once finished with the pancakes John turns to the tramp gesturing for him to get up and eat. The tramp seems to make some sort of comment about coming though makes no move to get up. Annoying John and causing him to go and take the paper from the tramp in response he lazily leaves the bed and splits the pancakes for them. This scene makes John look more like “the adult” in the relationship showing the tramps seemingly uncaring attitude. We see this type of behavior today with fathers leaving their children to be raised by their mother, an older sibling, or simply to raise themselves. Fathers in history have been required to do nothing more than work during the day and then come home and just relax. They would have been required to do all the cleaning, cooking, and childcare. However, we do see hints of the tramp caring for John, by cleaning him, bathing him, and having some general affection. This scene shows the uncaring attitude attached to men in film.

Although the tramp’s strong affectionate feelings are shown later on through the eventual separation from John due to the discovery that the tramp is not his father. Two orphanage workers with this knowledge attempt to take John away leading to this scene. Cutting between the tramp, currently struggling to get John back from an orphanage worker, and John. In a truck ready to be taken away. Through close-up shots we see John asking for help and the tramp realizing how much he cares for the kid. Through John we see a verbal ask for help from some passersby, desperately crying and pleading for action to help. From the tramp, you get a close-up shot showing the moment he realizes how much he cares for John. There’s a panic in his eyes as he looks at the camera and realizes that he’s losing John, a powerful realization for him and a heartbreaking one for the audience. Even though he later succeeds in getting John back from the orphanage workers. He eventually loses John due to a bounty put out for the return of John to his mother. I feel, as I touched on a bit in the previous paragraph, men have a tendency to hide or detach from deep emotions. This is due to society telling men that they need to be the strong ones in relationships, they need to be a shoulder to lean on, a fighter, a protector. Not a crier or someone who is in touch with their feelings. So in moments where, in this instance, the tramp’s child is being taken away. We see a sort of emotional break, where he realizes he loves John and he needs him. Not just as a companion but as his boy, his son.

With this loss, we get another, in my opinion even more powerful scene that shows Chaplin’s cinematic genius. To set the scene the tramp has just lost John and returns to their house yet is unable to get in. In response he twirls his hat twice while looking at the door, normally you’d expect screaming, crying maybe banging on the door in a rage. Yet instead we get a melancholy moment of silence in an already silent film. To explain it a bit better Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason break it down a bit better in the context of Kinesthetic Empathy, Kinesthetic Empathy is the ability of performers, or in this case, the audience, to decode and react to one another’s physical actions:

The extreme intensity of this moment is conveyed by one detail: the Tramp clumsily twirls his hat twice while looking at the door. Apparently nothing, yet a thousand times more powerful than any tear or facial contortion. The loss of the child is a catastrophe beyond qualification, which only silence can communicate. To communicate silence in a silent film, Chaplin expresses nothing and marks the deliberateness and forceful expressiveness of this choice with one of the most trivial of all possible place-holder gestures: twirling a hat. (Reynolds D., & Reason, M.)

This film also subtly comments on the difference between the upper and lower classes. Specifically, with John’s mother and the tramp, There’s less of a commentary behind John’s mother. As she is particularly generous with her wealth through a scene where we see her donate some toys she’s bought to children in the slum where John and the tramp live. The beginning of the film though has a much stronger commentary as mentioned above due to the mother having what we can assume to be little to no income. She abandons her child. What I didn’t mention was that she placed her child in what was then known as a limousine. This was obviously in the hope that the people who were more well off and the owner of the car would take care of John and give him a better life. Although in a twist of fate, the car is stolen and John is abandoned instead in a slum, and taken in by The Tramp. The twist of irony in this is not only that the life she was hoping to avoid giving her son was the life he got but also. The life she was trying to avoid is exactly the kind that gave John love.

The tramp is a better example of the discrimination put on the poor in this movie. That is because of the lack of income they are less able to take care of others. If they can even take care of themselves. This is particularly apparent in the scene leading up to John being taken from the tramp. When the doctor evaluating John is told he’s not John’s father he responds “‘This child needs proper care and attention’ – ‘proper’ referring to middle-class standards of propriety and legitimacy” (Korte 133). Even though the tramp, as we have seen, is perfectly capable of taking care of John. Even if it isn’t to a certain standard. We see these standards again when social workers arrive at the tramp and John’s apartment to take John away and, “[they] announced in a scathingly cynical title card: ‘the proper care and attention.’” (Korte 133). The man in charge of taking John away even sees the tramp as too lowly to speak to directly “but, class-consciously, uses his driver as an intermediary” (Korte 133). This shows in a twist of irony how they don’t actually care about John, or how well he’s taken care of. All they see is a man of a lower class who in their eyes is unfit to care for a boy that is not his own.

In conclusion, This movie is a beautiful commentary on the relationships a child has with their parents. And how those bonds can sometimes be misunderstood. As well as even with class differences we can’t judge how others can take care of their kids. As long as they are given love and care. We have made leaps and bounds in our society today, with gender differences. There are stay-at-home dads now, single parents with both genders, and for the most part, as long as you have a good income and a loving home your children are seen as safe with you. But in my opinion, we still have some of the same issues in our society as in The Kid. If one parent or both love their child with their whole being, yet don’t have the money to afford some things that the child might need, they are taken away. This is seen by some people as the way things must be. A parent in this society should be able to get a job and pay for their child. Yet we never take care to see the problem that some of these parents may be facing, we’re living in 2023. We should have more accessible jobs for struggling parents. Or specific groups that are well known that can help a parent or parents get on their feet. I know that there are companies like that out there, but this is obviously still a problem in this world. We need to work a little harder to try and fix it.

References:

- “Filming The Kid.” Charlie Chaplin.com (n.d.). Retrieved March 3, 2023, from https://www.charliechaplin.com/en/films/1-the-kid/articles/3-Filming-the-Kid

- Reynolds, D., & Reason, M. (2012). Kinesthetic empathy in creative and cultural practices. Intellect.

- Korte, Barbara. “New World Poor through an Old World Lens: Charlie Chaplin’s Engagement with Poverty.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 2010, pp. 123–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41158484. Accessed 20 Mar. 2023