4 Sabrina (1954)

Sabrina Fairchild: Treated Fair or Like a Child?

by Vivian Bratsouleas

In the film, Sabrina, produced in 1954 and directed by Bill Wilder, star Audrey Hepburn leads viewers through a competing love story. On the surface level of the story we witness the womanizing of two wealthy industrialists sway attention in Sabrina’s choice of love. The younger brother, David Larabee, uses his charms and clean-cut appearance to compel women. While his older brother, Linus, maintains his matters of interest solely on the family business and growing wealth, until Sabrina Fairchild turns both their heads. Audrey Hepburn plays Sabrina, a Cinderella-like character completely head over heels for a man who does not see her as anything but the neighbor chauffeur’s daughter. That alters after her brief but crucial experience in the world beyond the garage of the Larabee residence. Throughout the film Sabrina’s character becomes complex in her ability to change her mind while still being true to herself. We are faced with the undeniable division between classes and the privileges, or lack thereof, in material wealth. David is oblivious to Sabrina’s keen eye for him, and she is naive to the complexities of relationships and its messy folds. Issues that unveil include, but are not limited to: wealth and depiction of wealthy people; inequality in the areas of class, gender, and values; disparity between men and women; how costume design presents itself on and off film; power shifts; women’s self-worth and/or self-doubt tested; as well as unrealistic or extreme mindsets that can push people over the edge, resulting in an imbalance outlook on one’s self and others. Within discussion, this 1954 film will also be compared to the newer version produced in 1995, in comparing characterization and conflict developments.

Wealth & Division of Class

The Larabee family and the environment in which they reside are important to acknowledge as they are white and upper-class individuals. The industrialist structure appears in their family portrait scene (min. 2:44-3:30). The positioning of each member is revealing of their behavior: Linus is upright, straight, serious, and this reflects his business-oriented character who excels at maintaining a legacy of richness. David on the other hand smiles and his positioning on a chair is that of a child peering over the back end, not fully turned around or upright. David, acting like a player without considering the cost of emotional torment is an example of someone misusing their wealth for personal benefit. He is irresponsible and unaccountable, the epitome of a stereotypical playboy. When finding out that David is involved with the daughter of a potential business partner, Linus courts them together. Then, as Sabrina enters beyond the surrounding trees of Larabee parties, she becomes a threat to this planned out alliance, in which Linus has no intention of losing. Based on what is laid out in the beginning of the film, Linus will remain numb to the fact he is playing with people’s lives and will end up utterly alone if he is not careful.

Gendered Expectations in Film Form

In analysis of this 1954 film, we can see gendered expectations come to light in connection to America on Film, Chapter 10: Women in Classical Hollywood Filmmaking. Even though Sabrina is the focal character based on the film title, her power as a woman can be considered limited and/or oppressed when compared to the later version produced in 1995. Gendered expectations can be seen in Sabrina being sent to Paris to attend cooking school in the original, versus in a newer version, she works for Vogue Magazine contributing to various jobs working with fashion and photography. According to the text’s discussion of women’s films being geared towards the female audience, men still were the ones yielding their hand of authority in this genre. This is true here with the male voices including the director Billy Wilder, and accompanying male writers Samuel A. Taylor and Ernest Lehman. According to America on Film, “Consequently, the woman’s film usually presents conventional, patriarchal ideas about what it supposedly means to be a woman. Centered on the lead female character’s romantic and/or domestic trials and tribulations, women’s films present the family and home environment as the proper sphere for women,” (233). Though this time period exemplifies a moment in history where feminism was achieving independence and gained freedom for women, old views still persisted in cinema. The text discussed the dividing categories of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ jobs. Makeup and costume design fell under the category of masculine, while positions like secretary were an example of a feminine job requiring minimal effort or creative expression. In the scene of David meeting with Linus at the office building, we are shown the dynamic of business and white men dominate the workforce with higher level positions. Secretaries consist completely of females, lined up in a row by the wall, typing in an orderly manner; heads down and taking demands (min. 27:05-28:07). The act of leveling up and ascending in the elevator could be reflecting the time’s ideology and faith–or lack of–in the ‘American dream’ which goes parallel with this Cinderella character being saved by a man securing protection. Additionally, in the scene of Sabrina and Linus in his office space, she begins to cook dinner for him and represents a woman partaking in the traditional environment and function of a cooking housewife or significant other.

The category of women’s films or chick flicks contain qualities that hinder women’s outlook on their own gender can be seen in the story revolving around Sabrina’s tragic reality that David will not love her. The text added, “Also, as terms like ‘tearjerker’ indicate, these films appeal directly to viewers’ emotions, on the assumption that women are more emotional than men. Thus, while the woman’s film genre presents a special niche where female characters were front and center, patriarchal notions of gender were continually reinforced,” (233). This emotional aspect is evident in the extreme act Sabrina takes in her attempt to commit suicide due to her strong but unreciprocated love with David (min. 13:43-15:39). In turn, she runs away to escape heartache and her habitual life that she so desperately wants to change. Her character in a way is portrayed as weak compared to David who disposes of women like material objects (toys/trophies). Women were portrayed with a protective father figure and/or spouse in early images of women in film, especially in this later 1950’s portrayal. This exudes the idea that a man is needed to stay relevant and afloat in society. In regards to men being a necessity to happiness, the familial relationship Sabrina shares with her father is evident of this idea. The film makes a statement about the connection to gendered expectations. In the window frame, closeup scene of Sabrina and her Father discussing her leave for Paris (min. 8:56 – 9:46). The father expressed, “Don’t reach for the moon child,” and continued, “besides it never hurt for a young girl to learn how to cook, did it Sabrina?” (min. 9:36-9:46). This could be broken down in multiple ways: Sabrina needing to get her head out of the clouds to face reality, or reinforcing the idea to remain within the boundaries of what women are expected to do.

Costume Design Choices & Oppression

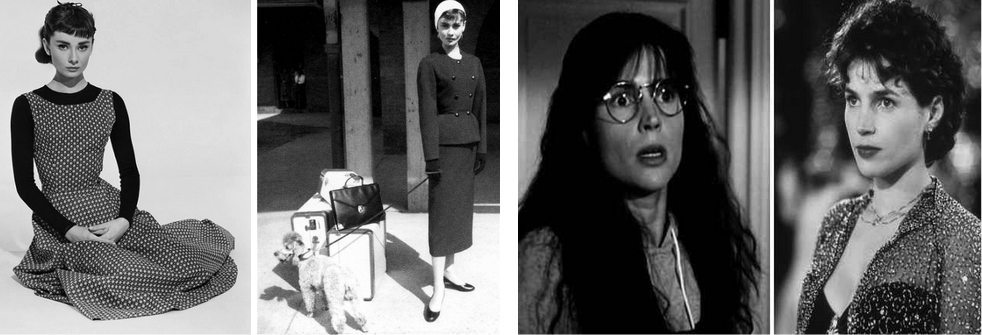

Additionally, we can study her character’s physical appearance and the choices made behind the scenes on her character. From beginning to end, Sabrina’s dress is tight-fitted and remains attractive throughout the film’s entirety. Even when she returns home in the Parisian transformed style with sophistication in her manner, it is not a clear jump from a pretty girl to an attractive woman. In contrast, 1995’s Sabrina has a complete transformation from long, unflattering skirts that were mismatched and frumpy in appearance to tight fitted and eye-catching. Similarities seen between both Sabrina characters was the physical alteration of hair to a short pixie cut-like length. This could be purposeful in achieving a more masculine look, which speaks out to women’s new found independence of the time.

As we saw, women were limited to feminine positions on screen; this was a struggle behind the scenes within the fashion industry field too. In the blog, “Designing Woman: Edith Head in Hollywood,” Amy Henderson reports Head’s efforts and achievements within the competitive studio system and its hegemonic atmosphere. Similar to the female filmmakers observed in Chapter 10 who had to adapt to the male dominated environment–with a changed dress or masculine manner being portrayed–Head acted in a parallel way in which she ‘downplayed’ her talent. Henderson shared, “She takes credit for two particular designs that became fashion crazes: the figure-loving sarong she invented for a slightly zaftig Dorothy Lamour in The Jungle Princess (1936), and the toreador pants she designed to emphasize Audrey Hepburn’s gamine grace in both Sabrina (1954) and Funny Face (1957).” Fashion designs on-screen were a catalyst for the market of department stores reflecting our time period’s evolving trends. This information is supported by the article, “The Power of the Screen: The Influence of Edith Head’s Film Designs on the Retail Fashion Market,” published January 1st 1982. Robert Gustafson examines Head’s indirect influence on consumers in retail with her design creations, especially to the actress of dress, Audrey Hepburn. Hepburn was ‘exotic’ and formed into a sexy movie star with her alluring costumes, including her white gown she wore to the Larabee party and her silk black cocktail dress with gloves she wore on her night out in NYC. Laurie Brookins discussed the controversy Head faced with her own vision for Sabrina and Wilder’s interests in her piece, “Story of a Dress: ‘Sabrina’,” updated March 1, 2020. Brookins quoted another source on Head’s hardship: “The director broke my heart by suggesting that, while the ‘chauffeur’s daughter’ was in Paris, she actually buy a Paris suit,” she wrote. “I had to console myself with the dress, whose boat neckline was tied on each shoulder — widely known and copied as ‘the Sabrina neckline’.” Costumes were tailored to those in higher positions including: art, set directors, amongst other people. Head was overpowered in her opinion, even as a female dressing a female, she had to make sacrifices in the midst of the male views of Givenchy and Wilder, who aimed at creating an aesthetic that fueled the male gaze.

Power

Power was a clear issue being fought behind screen, and the same could be said for the on-screen events faced by the main characters. In the Larabee meeting scene, only one of the five business people with Linus were female, and all were white and older in age. This scene verifies the industrialists level of power with zoomed in focus on Larrabee Industries Ltd. and floor level being high up; physical and metaphorical distance between class (min. 27:05-28:07). In the scene of Linus dancing with Sabrina in the golf courts, Linus explicitly states his views on reasons why Sabrina should place her priorities elsewhere. The exchange of dialogue with the background melody of “Isn’t It Romantic” adds irony to the shots taken between Linus and Sabrina. Sabrina is caught off guard, especially when Linus delivers, “It’s all in the family,” (min. 1:01:25). He doesn’t see this as more than a business deal or competition in which he will undoubtedly achieve since he has all the money he could throw at Sabrina to put her attention elsewhere. Chapter 9 of our text mentioned, “Comedies and musicals like How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Sabrina (1954), and Funny Face (1957) showcase an abundance of fashion, furniture, cars, and new consumer goods for audiences to appreciate, envy, and eventually purchase,” (197). In connection to money, the first shot of the film overviews the Larabee estate–including a freshly cut garden, fountain, boats, aircraft, tennis courts, and indoor/outdoor swimming pool–as well as the scene of Sabrina in the garage full of luxurious model cars.

Additionally, the play on Sabrina’s innocence and Linus’s experience comes to light as she is still new to navigating life in a more realistic than fantasy outlook. As previously mentioned, the ‘Cinderella-figure’ is toyed with here as she feels like she is living out her dream and is interrupted by Linus, who makes it clear she needs to remember her place. Chapter 9’s Corporate Hollywood and Labor in the 21st Century discussed the displaced focus on materialism even with economic exploitation. Both Sabrina film’s could be categorized as chick-flicks and both meet the detail of a Cinderella-figure entering the high urban life. Lastly, the scene of Sabrina mocking the board of directors meeting table yields the creative device of satire and captures the levels of class and power (min. 1:15:00 – 1:15:23). The wider shot captures the indoor setting of business and the outdoor setting with action of industry at work. The working-class operates in factories and ensures ships are operating, while the higher ups wave their hands of direction from a distance. The use of satire by Sabrina confronts the harsh reality of society divided by wealthy industrialists; economic problems hit the servants, making it difficult to move up. But the ‘American dream’ idea lives on here as Sabrina herself is now dressing in more luxurious fittings and attending Linus in events she did not experience before. The cinematography binded with the sound effects similar to the dooming instrumental played in the wicked witch, twister scene of Wizard of Oz (1939) matches the spinning chair movement and the condemning reality of business and its consequential strings.

The effect of U.S. postwar foreign policy on cultural and economical discourses is transcribed into the film mode of communication. According to Dina M. Smith’s Cinema Journal article “Global Cinderella: Sabrina (1954), Hollywood, and Postwar Internationalism” the discourse is shown in Sabrina who completely transforms into a Parisian (European) figure, and over the course of seduction received by Americans (Linus and David), she is used for profit. After WWII, Paris was viewed as “international gamin” in terms of social/international relations for the U.S. (Cinema Journal 41, No. 4, Summer 2002; p. 27). During the fight against rising communism, French sided with the U.S. which resulted in strengthening U.S.’s economic hold and military hegemony with reconstruction goals. Postwar, the U.S. benefited from European relations in the areas of trade and French fashion that expanded throughout the American market. This spread of Americanization during the Cold War hit Europe hard with exigent culture anxiety. Smith examined, “Sabrina fixates on its title character as a European emigre (literally since its star, Audrey Hepburn, was a Belgian World War II refugee) and on her ability to export and teach the lessons offered by Europe. Thus, French cooking, poetry, fashion, romance, and style become the film’s antidote to America’s buy-and-sell culture. Postwar France is a glamorous ingenue waiting to be consumed, her cultural capital vital to postwar America’s emerging cultural hegemony,” (34). Just as seen throughout America on Film, Hollywood is competitive in remaining in the spotlight for consumer profit and producing popular stories that entertain as well as place them on a pedestal of control. Smith analyzed Linus’s character played by Bogart: “Bogart is still the internationalist, but Wilder illustrates the ironic underside of the heroic image of American intervention shown in Casablanca. Linus sees other countries in merely transactional terms; he travels to Iraq for oil deals, and although he occasionally stops in Paris, he never leaves the airport. Linus’s unmarried status-his resistance to romantic involvement-recalls Rick’s isolation-ism. By film’s end, however, Linus sails off with Sabrina to Europe, engaged to both the girl and the Continent,” (34). Sabrina exemplifies this notion of white patriarchal capitalism being used to exploit humanity’s diverse individuals.

Conclusion

In the end, this surface level romance-comedy genre film may have stayed within the era’s parameters of film form–invisible style, linear narrative with a love interest–but a story of growth takes place as Sabrina transforms from a childlike female to an independent, strong headed woman. This transformation from innocent, naivety to an adult ascending off in the real world with its complicated hardships undeniably broadens all viewer’s understanding of love, life, work, and balance. Linus steps down and makes choices for himself alone, realizing there is more to life than work. After watching the original version from 1954 and the newest version from 1995, both are valuable in acknowledging difference, power, and oppression within film. Though both films have defining differences–one aspect being that one is black and white, and the other in color–Sabrina Fairchild’s character remains the prime voice of power. Particularly, in the 1995 film her portrayal is more realistic and grows gradually, rather than abruptly. This is evident in the absence of Sabrina attempting to kill herself over a man who does not see her worth or beauty before and even after her Parisian transformation. Additionally, the portrayal of Linus in the later version could be argued in revealing a side of vulnerability, rather than fixed machismo, to the unknown power of love that Sabrina guides him through. Sabrina choses to go to Paris for herself, not for Linus. In both “happy endings” the man chases after the woman instead of it being the other way around.

References

Benshoff, Harry M., and Sean Griffin. America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Wiley-Blackwell, 2021.

Brookins, Laurie. “Story of a Dress: ‘Sabrina.’” Screen Chic, 2 Mar. 2020, www.screenchic.com/post/story-of-a-dress-sabrina#:~:text=Hepburn%20selected%20three%20looks%20from,of%20a%20black%20strapless%20bodice.

Gustafson, Robert. “The Power of the Screen: The Influence of Edith Head’s Film Designs on the Retail Fashion Market.” ProQuest, The Velvet Light Trap, 1 Jan. 1982, www.proquest.com/openview/7f0af9265b5c382eebc148d071658230/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1816652.

Henderson, Amy. “Designing Woman: Edith Head in Hollywood.” National Portrait Gallery, 6 July 2010, https://npg.si.edu/blog/designing-woman-edith-head-hollywood.

“Sabrina.” IMDb, IMDb.com, 15 Oct. 1954, www.imdb.com/title/tt0047437/?ref_=fn_al_tt_4.

Shannon. “Sabrina (1954), Audrey Hepburn, & Givenchy.” Vanguard of Hollywood, 21 Apr. 2023, https://vanguardofhollywood.com/sabrina/.

Smith, Dina M. “Global Cinderella: Sabrina (1954), Hollywood, and Postwar Internationalism.” Cinema Journal, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2002, pp. 27–51, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1225787.