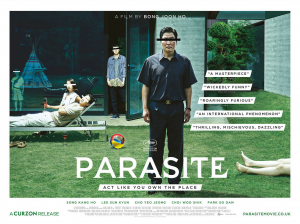

96 Parasite (2019)

Class, Colonialism, and Gender in Parasite (2019)

By Colson Legras

Throughout the history of cinema, especially in our modern, information-saturated, on-demand world, the English language has dominated the film industry and all forms of media at large. This has made the average person prone to becoming overly accustomed to a predominantly English-language media environment at the cost of exposing them to works from languages and cultures outside the Anglosphere’s influence. As a result, it is very common for English-speaking viewers to have more difficulty connecting or relating to stories that aren’t in the English language and require subtitles. This too often leads to a clunky and disconnected viewing experience.

The 2019 Korean genre-hybrid film Parasite breaks free from those typical restraints by offering a compelling and captivating narrative experience combined with a universally relatable message of the injustice of increasing class and wealth inequality in the world, while also touching on issues of gender and colonialism. More than anything else, the film presents its social message in a way that seamlessly translates across language and cultural barriers thanks to its masterful editing, mise-en-scene, cinematography, music, acting, and writing. Interspersed throughout the film are countless implementations of these elements of film form to illustrate the differences between two South Korean families, how their interactions highlight the power dynamic between them, and the distinct ways they each interact with society due to these differences.

Parasite entered the public consciousness among growing awareness and frustration with the rise of wealth inequality and its perverse effects on governments, individuals, and society as a whole, which if anything, have only gotten worse since the pandemic. The film echoes the grievances many people hold with capitalism, poverty, and the existing social order. Its setting in South Korea is relevant, although not integral, to the films’ overall purpose of portraying inequality and social mobility in a very cynical and pessimistic light. In her review of the film, The New York Times’s Michelle Goldberg calls this approach “bracing” due to its raw and honest presentation of these themes and stark contrast with typical sensibilities about class distinction and social mobility in America, which tend to depict differences in social class in either a positive light or as a necessary evil (Goldberg).

Bong Joon-ho, the director and co-writer of Parasite, is no stranger to depictions of class differences on screen. As film critic Mark Kermode points out in his review in The Guardian, Bong’s back catalog of films, including Memories of Murder, The Host, and Snowpiercer, is well-known for not-so-subtle commentaries on wealth, power, and authority (Kermode). Parasite’s rendition of this class dynamic focuses on two Seoul families: the Kims, a poor and desperate family living in a basement apartment, and their goal of infiltrating and each becoming employed by the Parks, a very wealthy family led by the head of a successful tech company. Bong in several instances highlights the two families’ differences in wealth and social standing using a variety of methods. The first instance of this occurs very early in the film when we see the Kim family search all around their small apartment for a stray wifi signal (2:55). Most of the camera shots in this scene are medium to close-up shots meant to invoke a claustrophobic feeling from being in the tiny basement apartment, as well as to get a more intimate feel with the characters.

Mise-en-scene is very important in this scene as well, as we see just how small, cramped, and messy the Kim family’s apartment is, which is indicative of their social class. This can be contrasted with the portion of the film revealing the Park residence, which uses wide establishing shots (13:00) and camera panning around the entirety of the property (13:45) to give a sense of spaciousness, privacy, and pristineness, characteristics more associated with the upper-class. Kermode also mentions in his review the use of staircases and escalators to mirror the ascent and descent of the social ladder. During the Kim family’s infiltration into the rich Park household, the Kims’ father Ki-taek is shown ascending an escalator with the Parks’ mother (41:00), showing the Kim family’s ascent into a higher level of class and opportunity. In the second half of the film as their plan starts to fall apart, they are forced to return home in the middle of the night during a thunderstorm, scaling down several flights of stairs in the pouring rain (1:33:10). Using a series of wide shots, the Kim family descending the flights of stairs reflects their descending of the social hierarchy as their position in the Park household, and in turn their economic security, is compromised (Kermode). Another example that stands out is the difference in the diets of the Parks and Kims. The top-down camera angles and jump-cut edits at (39:50, 40:25) contrast the fresh fruit eaten at the Park household with the cheap, greasy pizza that the Kims eat together. Editing is also used effectively to highlight the difference in abundance and material wealth, when the Parks’ huge walk-in closet and wide selection of high-end clothes is juxtaposed with the Kims choosing from a pile of secondhand charity clothes (1:43:00).

With any story of class differences come the varying levels of power that the members of each class have, and in fact, the amount of power one has in society is a defining characteristic of one’s social class. In Parasite, the power of the Park family is evident throughout the film, as is the Kim family’s lack thereof. One of the ways Bong Joon-ho emphasizes the power that comes with elevated social status is through physical elevation. For example, the Parks have a housekeeper who lives at the residence with them and will do any chore and favor desired by the Parks on a whim, and is both physically and financially subservient to them. Her room is shown as being on the first floor (44:30), while each of the members of the Park family all sleep on the top floor, showing their position above the working-class housekeeper socially and literally. This is also echoed later in the film when it is revealed the housekeeper’s husband has been living beneath the house in a secret bunker. The Kim family’s overwhelming lack of power is on display as well. They find it difficult to persuade even a pizza shop worker to hire Ki-woo as a part-time worker (5:20), even as they all surround her. With a medium shot that gradually zooms in on the pizza worker, this is also an example of how the limited amount of power the Kim family does have is from their strength in numbers and ability to coordinate and work together, which is further explored later in the film.

As the narrative of Parasite progresses, so does the tension between the Kim family and the Park family, as well as between them and the housekeeper and her husband. As this conflict plays out in the foreground, a conflict rooted in class stirs up in the background, leading up to an explosive conclusion. Throughout the film, the Parks, particularly the patriarch Mr. Park, draw distinctions between themselves and their ilk and those below them on the totem pole, and discriminate based on those class distinctions. He emphasizes the value of subordinates who don’t “cross the line” (43:40) by involving themselves too much in his business or positioning themselves as his peers. In another scene, Mr. Park distastefully recounts to his wife the pungent smell which emanates from Ki-taek and “people who ride the subway” (1:28:40). This scene is particularly illuminating into the differences between the classes which the Kims and Parks are a part of and the attitudes and resentments they hold towards each other. While Mr. and Mrs. Park are shown lying together on their couch, the camera moves down to a low shot to show the Kims under a table within earshot (1:27:40). This repeats the allegory of representing class with one literally being physically above the other, while emphasizing the powerlessness of the Kims beneath them who are forced to stay silent and undetected.

The metaphor of smell to illustrate revulsion towards lower-class people is exhibited again in a later scene, when the Park family is preparing for an impromptu birthday party for their son, Da-song. The mother runs errands while being driven around by Ki-taek. In part due to the flood of sewage water which ravaged their home the night before, his smell was particularly noticeable to Mrs. Park, which elicited visible disgust from her. At the party, a dramatic and hectic scene played out in which the housekeeper’s husband, Geun-se, goes on a violent rampage which, among other things, results in himself being fatally stabbed. While trying to reach his car keys which became lodged under Geun-se, Mr. Park attempts to grab them but is visibly taken aback and disgusted by his smell (1:54:20). He also completely ignores both Ki-jung and Ki-woo, who are both bleeding profusely and need immediate medical attention, instead prioritizing the unconscious Da-song. This is emblematic of the apathy that Mr. Park has for those from a lower social class. In retaliation for his contempt and carelessness, Ki-taek spontaneously stabs Mr. Park in the chest, killing him.

Although the film is primarily a critique of class stratification and inequality, there certainly are other elements present. For instance, gender relations and roles are relevant to many of the characters’ identities, such as the Park’s daughter Da-hye and her ensuing relationship with the significantly older Ki-woo. The roles the female characters generally take on in the film when it comes to family life are relevant as well. The members of the Kim family all seem to consider themselves as equals, no matter the gender. A very insular and close-knit family, they prefer to cooperate and work together, each taking on a roughly equal role in the household. It isn’t until they immerse themselves in the household of the Parks and their upper-class environment that they begin to replicate gendered norms, such as the mother becoming the new housekeeper. The Park family, on the other hand, is much more patriarchal. The mother stays at home and takes care of the kids, while the father is the sole breadwinner of the household. He also seems to give preferential treatment to his younger son as opposed to his high school-aged daughter, only ever interacting with her to scold her. This depiction of gender in the film is representative of the notion that higher social class and wealth are often closely tied with male power in society and the fact that the higher up the social ladder you go, the more patriarchal it generally becomes. This is backed by data as well; CNBC’s Zameena Maija pointed out that in 2018, only 4.8% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies were female (Maija).

However, what strikes me as a particularly interesting element intertwined with the film’s themes of class and capitalism that lies in the background of the film is racial: the odd focus on Native Americans on the part of Da-song. He has a strange obsession with Native American tropes, carrying a toy bow and arrow, wearing a headdress, and camping outside in a teepee. His parents even theme his birthday party around them. Native Americans obviously don’t have a significant place among Korean race relations, so it seems odd to include in a Korean blockbuster film. I hadn’t even given this part of the film a second thought until it had been pointed out to me by a friend. Its symbolism becomes clearer upon noticing that every time that Da-song’s toys are brought up, his mother mentions that she “ordered it from the U.S.” (18:40, 1:27:20). The specificity of that phrase suggests it’s much more than a nod towards the perceived quality of American-manufactured goods. It seems to be a broader commentary on colonialism and imperialism, and how the United States expanded and exported these behaviors and ideologies along with capitalism during its 19th century westward expansion in Native American territory, as well as its postwar rise to global superpower status. This is specifically relevant to South Korea, which owes much of its existence and success to its alliance to U.S. political and military interests and adoption of neoliberal economic policy. In the same way that the Parks imported the teepee and bow and arrow as consumer products from America, South Korea imported America’s capitalistic, stratified social order, in addition to its commodification of cultures like we see with Da-song’s obsession with Native Americans. The climactic birthday party scene explores this concept further. Mr. Park and Ki-taek, both in Native headdresses, are about to surprise Da-song by pretending to ambush Ki-jung with tomahawks and “battle” with Da-song (1:48:00). This choice to portray Native Americans not as a group of people to be understood, but as a vague, faceless idea of antagonistic, warmongering savages is deliberate. It reflects the broader history of Native Americans on film and their legacy in general: the tendency of other more powerful groups to determine their stories and fate for them, rather than letting them determine it for themselves. In replicating this dynamic, the film does not endorse it; rather, it critiques it through imitation.

Social messaging aside, the film is also extremely engaging and enthralling and stands on its own even without the subtext of critique of inequality. All that said, I would instantly recommend this film to anyone, regardless of their interest in foreign films or desire to read subtitles, because in the case of Parasite, it easily ranks as one of the greatest films of the decade.

If there’s one thing Parasite does best of all, it’s bringing attention to a pressing social issue in a way that dissolves cultural and language boundaries and reaches a wide audience without compromising its cinematic complexity. It achieves this goal in a variety of ways; realizing its wider audience likely isn’t fluent in Korean, its acting, writing, and subtitling allows the viewer to effortlessly immerse themselves in the film’s world, making the cultural setting and language function more as a backdrop than as an obstacle. Most importantly, Parasite’s main takeaways, that wealth inequality is the result of factors largely outside one’s control, that class differences aren’t totally earned, and social mobility is a bygone dream for many, all have the potential to resonate with audiences from all cultural backgrounds. This is at the heart of why the film is so impactful both emotionally and culturally.

Parasite is uniquely significant for several reasons, many of which have more to do with public perception than the actual filmmaking process. The biggest reason this film is relevant to the public, myself included, is largely because of deep dissatisfaction with the effects of social stratification and a capitalistic culture on society. In particular, Hollywood, with its endless sequels, remakes, and the concentration of production rights into the hands of fewer and fewer media companies, is certainly a prime example of this. Filmgoers have noticed, and Parasite, both as a foreign film which turns genre conventions upside-down and as a critique of the typical cultural assumptions that Hollywood helps perpetuate, is a breath of fresh air from the fumes of Hollywood. The fact that, despite its language barrier, the film easily plowed through the Oscars to receive Best Picture and became many fans’ favorite film of the year proves that its idea of class inequality being arbitrary, unmerited, and unjust is resonating with more and more people each day. In many ways, Parasiteand the success it has spawned represent a massive ongoing paradigm shift in how we talk about issues like class, inequality, and the film industry: one that we’ll be feeling the ripple effects from for decades to come.

REFERENCES

Goldberg, Michelle. “Class War at the Oscars.” The New YorkTimes, 11 Feb. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/opinion/parasite-movie-oscar-inequality.html.

Kermode, Mark. “Parasite Review – a Gasp-Inducing Masterpiece.” The Guardian, 10 Feb. 2020, www.theguardian.com/film/2020/feb/09/parasite-review-bong-joon-ho-tragicomic-master piece.

Mejia, Zameena. “Just 24 Female CEOs Lead the Companies on the 2018 Fortune 500-Fewer than Last Year.” CNBC, 21 May 2018, www.cnbc.com/2018/05/21/2018s-fortune-500-companies-have-just-24-female-ceos.html.