1 First Half of the 16th Century

Expedition of Fortún Jimenez to Baja California

In 1513, a few years after the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the isthmus of Panama and discovered the Pacific Ocean. Balboa had solemnly “taken possession” of all the water of that ocean, and of all the lands bathed by it, thus reinforcing the rights of the Crown of Castile over the area.[1] Although some historians claim that in 1527 the navigator Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón, cousin of Hernán Cortés, sailed near the California coasts, it would not be until 1553, two decades after the signing of the Tordesillas Treaty that the Castilians would arrive in Baja California.

One of the first Hispanic sailors who navigated from New Spain was the pilot Fortún Jiménez. He started in Cozcatlán (present-day Manzanillo) following the coastline to the northwest, and managed to get to the port of La Paz, thinking that it was an island and not a peninsula. Once at La Paz, due to a terrible encounter he had with the indigenous population of the region, Jiménez and some of his sailors were killed, while the few survivors of the expedition managed to sail back to the coasts of Jalisco. The natives were likely Guaycura or Pericú, who were then disputing the territory and who responded to the violence and robberies exercised by the Hispanic navigators by confronting them.

However, it was Hernán Cortés, not Jiménez, who named this territory, when he sponsored the third expedition to explore the coasts of the Pacific in 1535. The sailors, under the leadership of Cortés and a trusted subordinate, captain Francisco de Ulloa, arrived once again at the present Bay of La Paz, which they now baptized as La Santa Cruz. There, after building a small village which they called Puerto del Marqués, the men stayed several months in the Bay, during which they had relatively peaceful contact with the Guaycura.

The explorers gathered some impressions of their way of life, explored the zone and even drew the first map of California. This was an anonymous and very simple map that included the coast between Cape Corrientes and the San Pedro and San Pablo rivers, along with the southern extreme of the peninsula, where the islands of Perlas and Santiago were also identified. In this map only the lower tip of the California peninsula is drawn, so it is not defined as a peninsula nor as an island.[2]

According to some authors, this very first map of California would finally turn the area into frontier land, so that it would no longer belong to the world of myth. The expeditionaries at first thought they had reached the lands of the mystic kingdom that appeared in a famous chivalry novel of the time, Las Sergas de Esplandián, written by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. As is well known, in the novel, written towards the end of the 15th century, appears the mythical island of California, populated by Amazons, governed by Queen Calafia, and said to be rich in gold.

The peninsula, and by extension, all territories located to the north of it were therefore named California. However, the first Spaniards that reached the bay of La Paz, rather than enjoying the mythical place that Rodríguez de Montalvo had spoken of, they found a land that caused them great disappointment. The hostility of the territory and the lack of water and food made them realize that the land they had reached possessed none of the riches they had hoped for.[3] Essentially, the only riches they collected were the pearls they had obtained from natives of the area.

ULLOA’S EXPEDITION TO SANTA CRUZ BAY

Cortés returned to Acapulco in 1536, leaving Francisco of Ulloa in the town they had founded at the bay of La Paz. This is where he would remain until it was abandoned indefinitely due to hunger and illnesses suffered by the colonists. Regardless of the harshness of the territory, Cortés sponsored a new trip, which Ulloa would undertake in 1539, with the purpose of exploring the sea that surrounded Santa Cruz Bay.

Ulloa set sail from Acapulco and after sailing north he entered the Gulf of California to reach the Colorado River delta. He named the place Ancón of San Andrés for having arrived there the day of that Saint, and Mar Bermejo (or Sea of Cortés), due to the reddish color that the waters gave it. Ulloa continued sailing until he recognized that the coast formed a peninsula, (although in later maps sometimes it continued to be represented as an island). That was the northernmost point of his navigation; he believed to have reached 34 degrees north latitude, even though they were really just over 31 degrees, Ulloa sailed back south until entering into the Bay of La Paz and reaching the southern tip of the peninsula. He then passed Cabo San Lucas and headed north to the island of Magdalena, where Ulloa was wounded after a confrontation with the Natives.

In April 1540 they found the island of Cedros (The Natives called the island Huamalgá, which means The Nebulous) where they remained for about three months waiting for fair weather. Ulloa sent several reports to Cortés before attempting to continue north. Due to the winds, Ulloa only reached a nearby cape, which he named Del Engaño (it could well be modern-day Punta Antonio or Punta Baja), and from there they had to return to La Paz. Once there, they sailed again to Cedros island. Ulloa sent one of his ships to inform Cortés of the discoveries while he attempted to continue his explorations north with a few sailors on board of a ship that eventually would get lost in the sea. Nobody ever heard of him again.

Baja California Natives

It was Ulloa and his men who first established contact with the Natives from the western coast of Baja California, even getting to observe some of their differences with other indigenous cultures. It was likely that all of them were Guaycura and Pericú, the nations that inhabited the coasts in some of the places that Ulloa visited, like the Bay of La Paz, Magdalena Bay, and the island of Cedros. Ulloa was surprised both by the number of trees that were there, hence the name, as well as by the canoes that the natives made and used with great skill.

The Pericú (also called Edues or Coras) had lived for more than ten thousand years in southern Baja California. The Guaycura (Guaicura or Waicura) lived in the central area, and the Cochimí lived in the extreme north. Like many of the indigenous peoples of the western coasts of North America, they were nomads who survived off of hunting, fishing, and harvesting. They exploited the marine and terrestrial resources of their environment without large settlements or agriculture.

Baja California natives were substantially different from one another, and while they had similarities in terms of language, this did not prevent them from having continuous conflicts with each other. Those who inhabited the northern territories belonged to the ethnic-linguistic group of the Yuman–Cochimí family. The majority of the ethnographic information about the Guaycura and Pericú (which were those with whom Hispanic navigators had some contact during the first half of the 16th century) comes from the explorers who arrived with the missionaries who later attempted to evangelize them. All of them highlighted their austere way of life, mainly due to the difficult and hostile conditions of the territories they inhabited.

Lack of Hispanic establishments in the 16th century

Already during the first few years of the conquest of the continent, the Pacific coast of today’s United States was explored by Spaniards. However, the Spanish monarchy’s influence on the north coast was limited due to its concerted efforts at conquering the central and southern American territories, the Philippines, and the Pacific coast, all at the same time. For this reason Spain did not initiate permanent establishments on those lands.

It was not until the end of the 18th century, upon receiving news of Russian and British intentions to settle the territories, that the Spanish monarchy moved to stake claim to these lands. The Crown sent numerous expeditions and aided the establishment of the first settlements on the Northwest Coast of the Americas, with the goal of expelling the other European powers. However, even though the Spaniards did not officially establish themselves in the Pacific Northwest during that time, they did initiate exploratory voyages to those territories at the end of the first half of the 16th century. The voyages’ objectives were to find a path east, to the mythical islands rich with gold and silver, and to chart the discovered territories in order to protect Spain from their European enemies.

Navigating the Colorado River & the First Map of Baja California

A year after Francisco de Ulloa reached the southern end of Alta California and discovered the Colorado River, Hernando de Alarcón set sail from the port of Acapulco with instructions to sail to the Sea of Cortés and navigate the Colorado River until reaching its confluence with the Gila River. After this expedition, the first complete geographical chart of Baja California was drawn, depicting it as a peninsula, not an island. When Alarcón returned to Mexico, his account of the expedition and the completed maps aroused the interest of the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza.

This viceroy was interested in exploring the coast of California and searching for a passage east to the Atlantic Ocean. He thus decided to send an expedition led by the sailor Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, with instructions to explore along the Pacific coast of California and navigate as far north as possible. The report of the discovery made by Juan Rodríguez, Relación del Descubrimiento que hizo Juan Rodríguez navegando por la contra-costa del Mar del Sur al Norte, written in 1542 by Juan Páez, explained in detail the expedition.[4]

According to Páez, Cabrillo set out from Puerto de Navidad on June 26, 1542 with two ships: the galleons San Salvador and Victoria, accompanied by a small brig named San Miguel. On August 5th he arrived at the previously discovered island of Cedros (at 28 degrees latitude) and later entered waters which no ship had yet navigated.

By the middle of August, Cabrillo’s party had reached a latitude of 30 degrees. On August 19th they visited the island of San Bernardo, and on the 20th, they reached Punta del Engaño, at 31 degrees. Two days later, Cabrillo and his men reached a latitude of 31.5 degrees and went ashore. The expedition claimed the land in the name of King Charles I and Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, and named it Puerto Posesión (actual Port San Martín in the bay of Saint Quintin). There the explorers tried to get acquainted with the fishing Natives “who ran away when they saw the Spaniards, but later took one of them, charged a ransom and was then released.”[5]

The Kiliwa, the Kumai, and the Kizh

These Natives were surely Kiliwa, a group belonging to the Yuman linguistic family from the north of the Baja California peninsula. The Cucapa, Pa ipai, Kumiai, and Tipai also resided in the area. These Native groups were descendants of the first humans who reached the peninsula, which was at least ten thousand years ago. They moved seasonally throughout the expansive territory, looking for prey and edible flora, and fishing or collecting mollusks when they reached the coast. The meeting between Cabrillo’s party and the Kiliwa was marked by mistrust. Although the scouts remained in the port until August 27th, they had no further contact with the Native group and dedicated themselves to preparing sails and stocking up on water. Four days later they saw smoke and traveled towards them by boat where they met another thirty Natives from a fishing village:

(…) of whom they took a boy and two Indian women to the ship, where they were dressed and given gifts, and then let go; they could not understand anything [from them, not even] using signs (…). [After five days], while going to drink water, they found certain Indians who were at ease and who showed them a water tank and a salt pan, of which there was a lot; and they communicated by signs that they did not live there but inland, and that they were a lot of people. That same day five Indians came to the beach in the afternoon, [and] they [were] brought to the ships. They appeared to be Indians of reason, and when entering the ship they pointed and counted the Spaniards who were there, and communicated that they had seen other men like them, who had beards and brought dogs, and crossbows, and swords. The Indians came smeared with white polish on their thighs, body and arms, and the polish looked like gashes, and they looked like men in stabbed leggings and doublet, and they pointed out that the Spaniards were five days away, and also that there were many [more] Indians, and they had lots of corn, and parrots, and came covered with deer hides, treated in the way that Mexicans do the hides that they use in their cutaras.[6] They are tall and willing people, they bring their bows and arrows like those of New Spain, with their flinted arrows, and the captain gave them a letter for them to take to the Spaniards they said were inland.[7]

They were most likely talking about Coronado’s or Alarcón’s men.[8] In any case, the ship departed from the Puerto de la Posesión on Sunday, August 27th, 1542. They found an island two leagues from the coast, to which they named San Agustín (actual Saint Martin). The men were there until September 3rd when they kept sailing with good weather. On September 7th they reached a cove, and a day afterwards, with opposite winds and few currents, they arrived to San Martin Cape and the cape of Santa Maria, (called Ja’ Tay Juwaat U’ in Kiliwa and later cape Colnett of Point Colonet by the English, to the north of Saint Quintin). At 32 degrees and a half they encountered other native populations, with whom they could not communicate.

From there they went to Cabo de la Cruz (currently Saint Thomas Point) at 33 degrees, where they once again saw Indians in canoes and continued sailing to a port they called San Mateo (currently Todos Santos Cove). It was a good enclosed port, where they drank water from a small pond and saw herds of animals like cattle that walked by the hundreds and resembled the sheep of Peru.[9] At 33.5 degrees, they went ashore and took possession of the land; they remained at that port for a few days and then continued sailing until 34 degrees.

A little later, at 34 and one third degrees, the expedition members found a port they called San Miguel (now San Diego), where they met again with Indians who told them through gestures that people like them had passed inland. That same night, some of the men from the expedition went ashore to fish with a net, and three of them were wounded by arrows from the Natives. During the next two days, Cabrillo’s men had contact with local Natives once again, who told them that inland were more people like them, that with crossbows, swords, and on horseback, had killed Natives, which is why they feared them. According to what the expedition members could understand, they called the Christians guacamal, which in their language meant ‘foreigner’.[10] Surely these natives were Kumiai or Kumeyaay, also belonging to the Yuman group.

After suffering the first storm of the season in the port of San Miguel, Cabrillo’s men set sail on October 3rd in order to sail north once again. They passed through some islands they named in honor of their boats as San Salvador (current island of Santa Catalina) and Victoria (current island of San Clemente). This is where they once again had brief contact with the Natives; surely a Tongva group that lived in the islands of the South Channel, one of the tribes of the Takico group that had inhabited those territories for at least ten thousand years, belonging to the linguistic family of Uto-Aztec, also called Kizh, and later named as Gabrielinos.

At 35 degrees they arrived at what they called the Bay of Fumos, or Fuegos, (also called San Pedro Bay, current Los Angeles Bay); shortly after that they arrived at a native town by the sea with large homes “similar to those of New Spain.” They called the village Pueblo de las Canoas (Town of the Canoes) because of the many canoes that belonged to the natives. Cabrillo’s men managed to communicate with the natives through hand signals, who told them that inland there were Christians, like them, whom the natives called Taquimines.

The Chumash

Pueblo de las Canoas was a large village of Chumash Natives, who spoke Ventureño and called their place Humaliwu, ‘the place where the waves sound loud.’ The Chumash, whose name derives from Michumash and means ‘shell-bead money makers,’ had been established in the area for about ten thousand years. At Cabrillo’s arrival, the Chumash were a large and important population, whose most ancient sites are to be found in the Santa Bárbara Channel. They had towns both on the so-called Anglo-Norman Islands (Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel, and even on the small island of Anacapa, where they lived seasonally due to their lack of water), and on the coast, as well as inland. They inhabited the central and southern California littoral regions, from the Morro Bay in the north to Malibu in the south. The Chumash population was more highly concentrated, though, in the coastal area, from the Malibu Canyon south to Punta Conception.

The name Chumash was given to them by ethnographers in the late 19th century and comes from the word used by the natives of the Santa Bárbara area to identify the Channel Islands inhabitants. There was no Chumash tribe but rather a set of independent towns and confederate towns, with populations from sixty to a thousand. The social organization of the Chumash was stratified and the different positions were linked to birth; thus, the position of chief (wot) was hereditary.

They had guilds of highly specialized artisans who made different utensils such as baskets, vegetable fiber twine, projectile points, shell bead money, and especially a type of canoe known as a tomol (also used by the Tongva of the Los Angeles area, who called it tii’at). These canoes, made of redwood planks, moored or sewn with ropes made of natural fibers, usually sealed with tar and pine resin, and painted and decorated with shell mosaics, were the ones they sailed with, establishing a wide commercial network. Some archeologists have even linked the tomols of the Chumash with contact and possible exchange of knowledge with navigators from Polynesia.

Undoubtedly, the tomols were both the highest expression of their maritime culture and an important symbol of the identity of the Chumash. In fact, they called themselves Tomol people and their canoes ‘houses of the sea.’ Even today Chumash indigenous descendants have built tomols that can be seen in different museums in Santa Barbara. Not surprisingly, tomols caught the attention of Rodríguez Cabrillo’s men, and for this reason the town in which they first saw them was called Pueblo de las Canoas (present-day Malibu).

Rodriguez Cabrillo’s Expedition Continued

Cabrillo’s men thus arrived in Chumash lands, and after claiming possession of the place, they remained there until Friday, October 13th. They continued sailing towards an island they called San Lucas (in the Northern Archipelago or Channel Islands of California), observing Indians in canoes, coastal towns, and corn plantations throughout the journey. They also received more news of the existence of Christians like them in those lands. On October 18th they reached what they called Cabo Galera (now Point Conception), at 36 degrees. From the town of Las Canoas to Cabo Galera they found about 30 leagues of a heavily populated coastline; according to the expeditionaries the entire area was inhabited by the Xexo Tribe (from the lee of Point Conception to Dos Pueblos, in the county of Santa Barbara). Between the tribes there were many different languages and wars with one another. From there, Cabrillo’s men sailed towards an unnamed port, from where they navigated with contrary winds, without being able to sail above 36 and a half degrees. Ten leagues north of Cabo de Galera the contrary winds continued and they had to return to seek shelter at said cape, where they went ashore to look for firewood and water. They called this shelter Todos los Santos. From there they went to a town, which they named De las Sardinas (present-day Santa Barbara), because of the abundance of sardines. There they collected drinking water and firewood for several days with the help of the natives, called the Xoxu (who inhabited from Las Canoas to the town of Las Sardinas, in present-day Santa Barbara County). An Indian woman from those towns spent two nights in the flagship.

On Monday, November 6th, 1542, Cabrillo left the town of Las Sardinas in direction to Galera, where they arrived on the 11th. All that day they navigated twenty leagues of coast without any shelter, noting the mountain range on land. The expedition did not take note of any populations but saw mountains at 37 degrees, which were called Sierras de San Martín (current Sierra de Santa Lucía). It was then that for two days a storm broke that made them lose sight of their accompanying ship. On Monday, November 13th, the wind finally settled. Although they went in search of the missing ship around the land, they thought that it might be lost, so they sailed north, always keeping near the coast in case they found a good port to repair their ship. However, the sea was rough, the coast inhospitable, and the mountains very high. They could not recognize a point where they could disembark until reaching 40 degrees. There, on Wednesday the 15th, they came upon their accompanying ship again and thanked God for finding it. On Thursday, they woke up in a large inlet and sailed it throughout the day and into the next; however, as they found no shelter and did not dare go ashore to claim possession of the land because of the turbulent sea, they dropped anchor. It was a cove, located at 39 degrees, and since it was full of pines, they called it Bahía de los Pinos (current Monterey Bay). On Saturday they sailed along the coast and found themselves at Cape San Martín. The mountains that could be seen in the distance were called the Sierra Nevadas (the northernmost area of the Sierra of Santa Lucia). The cape at the beginning of said mountains, at 38 degrees and two thirds, was named Cabo de Nieve. From Cape San Martín, which is at 37 and a half degrees, up to 40 degrees, they saw no signs of any native inhabitants. They returned to the islands of San Lucas, and they anchored in Posesión, named Ciquimuymu by the Chumash (current San Miguel Island).

While wintering on this island, Cabrillo died on January 3rd, 1543, as a result of an injury from a fall during his previous visit to the island. The fall resulted in a broken arm (although some authors claim that the wound was the result of a skirmish with the native islanders).[11] The name of the island was then changed to Juan Rodríguez. Before he died, Cabrillo transferred command of the expedition to his pilot, Bartolomé Ferrelo, whom he ordered to continue sailing when the weather allowed, insisting that they should not stop discovering everything possible along this coast.

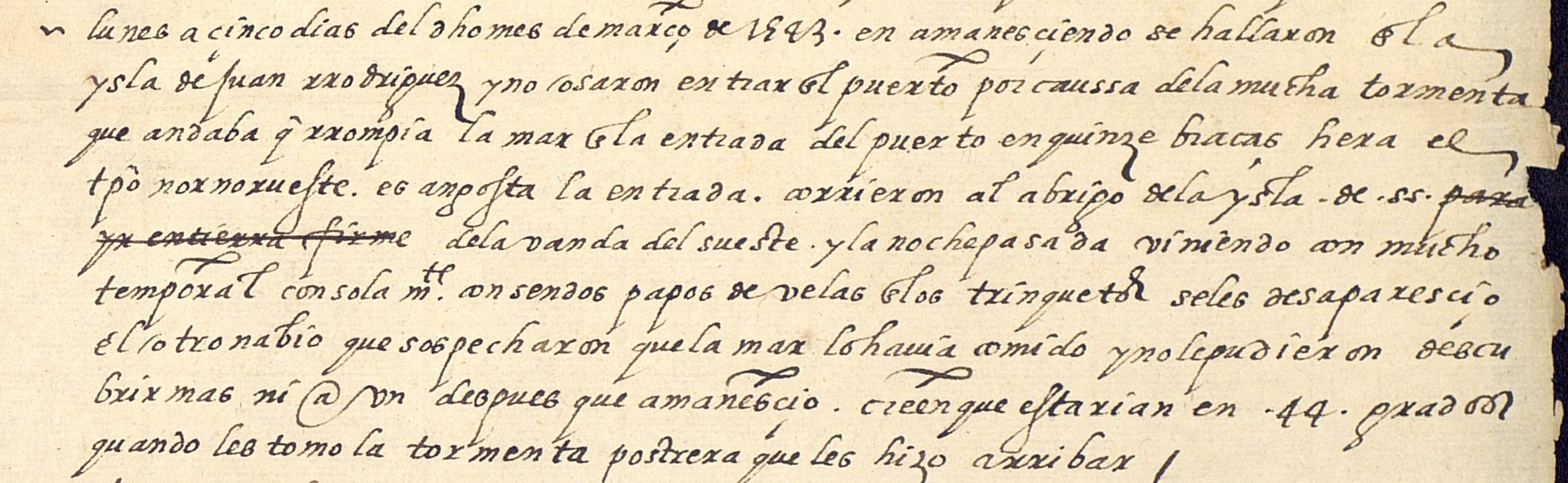

At the end of January, the explorers departed to the island of San Lucas to collect some anchors they had left there. After the storms, during mid-February, Bartolomé Ferrelo continued sailing north, heading towards the port of Sardinas, while enduring bad weather. On January 22nd they were sailing in search of Cape Pinos (present-day Point Reyes), reaching it in four days. They continued sailing without seeing signs of populations along the coast. On Wednesday, January 28th, they could measure that they were at 43 degrees (somewhere near or at the elevation of present-day Port Orford, Oregon):

( ..) [then] it became a cool night, the wind jumped to the south-west, they navigated that night to the northwest with a lot of work and on Thursday, at dawn, the wind leapt into the south-west with great fury and the sea came [to the ship] from all sides, greatly fatiguing them; the seas [even] passed over the ships that did not have bridges, and if God did not help them, they would not have escaped. Unable to get to safety, they went to the northeast on a turn of the terrain. They thought themselves lost there and prayed to Our Lady of Guadalupe and made vows, and they worked like this until three hours after noon, with great fear and travail because they feared they were about to die, and saw already many signs that land was nearby, including birds and fresh sticks that came out of the rivers. However, with such great darkness the land did not appear, and at this hour the Mother of God helped them, with the grace of her Son, and heavy rain came very fast from the northern part that made them run to the south all night and the next day until after the sunset. With the foresails very low, and because there was a lot of sea from the south, it was charging from the bow every time and passed through them as if through a boulder. The wind jumped to the northwest and north-northwest with much fury, which made them run until Saturday, March 3rd, southeast and east with so much sea that they were out of sorts, that if God and his glorious Mother miraculously did not save them they could not have escaped. Saturday at noon the wind settled and remained in the northwest, for which they thanked our Lord very much, and they also suffered from food, because they only had old stale sponge cake.[12] It seems to them that there is a very large river between 41 degrees and 43 degrees because they saw many signs of it. This afternoon they recognized the Cape of Pinos, and because of the rough seas they could not do less than going through the coast in search of a port. They suffered from the cold.[13]

By the dawn of Monday, March 5th, the expedition was already back on the island of Juan Rodríguez. It was impossible for them to land on it due to the bad weather, (which also caused the disappearance of the other ship; it is speculated that the storm took them at 44 degrees).

Three days later they arrived at the town of Las Canoas in search of the accompanying ship, but it was nowhere to be found. While there they took four Natives. They then sailed to the island of San Salvador, but again, did not find the other ship. They continued on until they reached the port of San Miguel. Again, the lost vessel was nowhere to be found and there was no news about the missing ship. In this port they waited six days and took two boys “as interpreters, to take to New Spain,” and before leaving they left certain signs in case another ship arrived. On Saturday the 17th of March they parted from San Miguel and on Sunday they arrived at the Bay of San Mateo, where they stayed one day until heading to the island of Posesión, where they waited two days in its vicinity without entering the port. The following Saturday at midnight they arrived at the island of Cedros, and they were still there on Monday the 26th, when the companion ship arrived at the island. On the 2nd of April, both ships parted to return from the island of Cedros to New Spain, as they didn’t have supplies to explore the coast. Finally, on Sunday the 14th of April they both arrived at Puerto de Navidad.

Thus, it was in this second stage of the trip, and after the death of Cabrillo, when the expedition reached the highest point in its navigation, which reached the coasts of the current state of Oregon. On the 28th of January 1543, the ships were found at 43 degrees, where the winds separated them and the ship of Martín de Aguilar went a little further north than anticipated. Bartolomé Ferrelo thus reached the northern limit of what today is the state of California, and he could even spot a place in the current state of Oregon, maybe Coos Bay, since, according to the expedition report, they must have gone up 44 degrees, but once there, without a secure coastal refuge, with the ships exposed to the strong winds and storms, they had to be governed on a course south, to the island of Juan Rodriguez, to return afterwards to New Spain.

FIGURE 1. Relación hecha por Juan Páez, sobre el descubrimiento que hizo Juan Rodríguez, navegando por la contra-costa del Mar del Sur al Norte. Para su viaje salió del puerto de la Navidad el 27 de junio de 1542.[14] [It documents the first time that the Hispanic expeditionaries sailed up to the latitude of almost 44 degrees, in the mouth of the river that they named and later wrote down in numerous maps as Martín de Aguilar (currently Coos Bay)].[15]

The Relación, sobre el descubrimiento que hizo Juan Rodríguez,[16] written by Juan Páez, explains in detail the trip made by Cabrillo and Ferrelo. The geographical information that was provided was not collected in the cartography of the time, or at least it seems that no map has been preserved; this caused that the expedition was not valued as the very important achievement that it was.[17] As written by the sailor and geographer José Espinosa y Tello in the Relación del viaje hecho por las goletas Sutil y Mexicana en el año de 1792 para reconocer el Estrecho de Fuca,[18] published in 1802: “when speaking of the expedition of Cabrillo it is necessary to insist that his boldness and fearlessness is worthy of admiration, taking into account the art of navigation at that time, the class of ships which carried out the expedition and the weather that accompanied him during the trip.”

Espinosa y Tello also notes that, if in history the merit of Cabrillo has been undermined, it is above all because several writers, such as John Knox in his New Collection of Voyages & Travel, published in 1767, when talking about Francis Drake believed that:

In 1579, he gave the name of New Albion to the coast between latitudes of 38 and 48 degrees because he believed that no other sailor had ever seen it, and writing later on about the port of San Francisco and its vicinities he added that in this country the Spaniards had never stepped foot nor discovered any land many degrees south of it.[19]

Espinoza y Tello also noted that Claret Fleurieu, in his work Travel Around the World During the Years 1790, 1791 and 1792 by Etienne Marchand,[20] published in 1799, tried to undermine the merit of the Spaniards. At one point he writes that Cabrillo did not go beyond the 44 degrees latitude, and in another he assures that the whole expedition was limited to sighting a cape at 41 degrees and naming it Cape Mendocino in honor of the Viceroy. Nevertheless, Espinoza y Tello insists that Cabrillo reached at least 43 degrees, and note in his work that the vessels of Cabrillo’s expedition:

(…) returned on February 22nd in search of cape Pinos, sighted it on the 25th and with the strong winds from the SSW they ran to the WNW, so that on the 28th they were at a height of 43 degrees, experiencing such strong winds and rough seas going over the ships, that they were unable to take shelter. They ran astern to the NE to a turn of the land with the risk and fear of getting lost, for the signs were there that the coast was close, and they could not see it because of the great storm clouds. They finally sighted it on March 1st and observed the latitude at 44 degrees, experiencing a very intense cold. They survived winds coming from the N and NW with downpours that forced them to run until March 3rd to the SE and ES, adding to the fatigue of the storms the lack of food because they had nothing left but sponge cake, and this was damaged. That day the time was paid: it seemed to them that between 41 degrees and 43 degrees a very large river empties, of which they had had long news, they recognized cape Pinos; and following the coast, they woke up on the 5th on the island of Juan Rodríguez, whose port they did not dare to take because of the great bursting at its entrance, and thus they ran in search of the shelter on the island of San Salvador, where at night there was a storm and the other ship disappeared temporarily. They believed it got lost, and they left to search for it on the 8th day, going to the town of Las Canoas, and successively to the island of San Salvador and to the port of San Miguel, in which they waited six days, taking two boys as interpreters, and leaving signs in case they were to arrive separately. On the 18th day they entered the bay of San Mateo; on the 21st day at the Puerto de la Posesión, outside of which they waited for two days; on the 24th day they arrived at Cedros island, and there the other ship joined, which passed to the island of Juan Rodríguez through shallow waters, where the ship was believed to have sunk. They left this island on April 2nd, and because they did not have enough supplies to continue discovering the coast, they followed to New Spain, entering the port of Navidad on Saturday the 14th of the same month.[21]

The different reports of Cabrillo and Ferrelo’s trip show that this expedition discovered the coast located between 38 degrees and 43 degrees thirty-six years before Francis Drake did it, and that the latter, believing that the Hispanics had not reached so high on their travels, was wrong. As it is known, in 1579 Drake had traveled from the coasts of Oaxaca to the north, and after navigating along the coasts of Alta California to Cape Mendocino, he claimed possession of a territory he called New Albion for the British Crown, thus ignoring the previous expeditions and their discoveries.

Thus, Drake should be only attributed with having first recognized the American Pacific coast between 44 and 48 degrees. Ss Espinosa y Tello concludes when speaking of the Cabrillo and Ferrelo expedition:

(…) from 1543, when Cabrillo made his voyage, until 1578, when Drake did his, there was no other navigator who had discovered up to 48 degrees. The true glory that can be attributed to the English navigator is having discovered the piece of coastline between 43 degrees and 48 degrees, which consequently should have limited its denomination as New Albion.[22]

- At the time, Spain was composed of two separate kingdoms: Castile and Aragon. The former had the exclusive rights of the discoveries and settlements in the Americas. ↵

- AGI, MP-México 6. ↵

- Rodríguez de Montalvo, Garci, Las Sergas de Esplandián, Imprenta de Juan de Juta Florentín, Burgos, 1526. ↵

- [Report of the Discovery Made by Juan Rodríguez While Sailing the Northern Coast of the Pacific Ocean]. // AGI, Patronato 20, N.5, R.13. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Rough, coarse shoes or sandals ↵

- AGI, Patronato 20, N.5, R.13. ↵

- The famous inland expedition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado from the City of Mexico to present-day Kansas took place between 1540 and 1542. ↵

- Pronghorns, as friar Junípero Serra called these animals. Diario de fray Junípero Serra en su viaje de Loreto a San Diego, edit. University of Texas, 2002. ↵

- Howe Bancroft, Hubert, History of California, 1542-1800, edit. W. Hebberd, 1963. ↵

- Research Yearbook, Volume 2, Science and Humanities Research Center, Dr. José Matías Delgado, 2002. ↵

- Sponge cake is bread without yeast and cooked twice, so that it would lose humidity and last long. ↵

- MECD, AGI Patronato 20, N.5, R.13. ↵

- [Account by Juan Páez About the Discovery Made by Juan Rodríguez Sailing Along the Counter-coast of the South Sea to the North. For his Trip, he Left the Port of Navidad on June 27th, 1542]. ↵

- MECD, AGI Patronato 20 N.5, R. 13. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Espinosa y Tello, Josef; Fernández de Navarrete, Martín; Alcalá-Galiano, Dionisio y Valdés Flores Bazán y Peón, Cayetano. Relación del viaje hecho por las goletas Sutil y Mexicana en el año de 1792 para reconocer el Estrecho de Fuca, con una introducción en que se dan noticias de las expediciones ejecutadas anteriormente por los españoles en busca del paso del Noroeste de la América, Imprenta Real, Madrid, 1802. [ Relation of the Journey Made By the Sutil And Mexicana Schooners in the Year 1792 to Recognize the Strait Of Fuca; with an Introduction that Gives News of the Expeditions Executed Earlier by the Spaniards in Search of the Northwest Passage of the America]. ↵

- Knox, John. New Collection of Voyages, Discoveries and Travels, vol. III, edit. J. Knox, Londres, 1767. ↵

- Fleurieu, C.P. Claret. Voyage autour du monde, pendant les annés 1790, 1791 et 1792 par Etienne Marchand, De l´imprimeire de la République, París, 1799. ↵

- Espinosa y Tello, op. cit. ↵

- Ibid. ↵