14 The Last Expeditions

The expedition of Jacinto Caamaño

There were a few expeditions carried out at the end of the 18th century. In 1792, Jacinto Caamaño alongside pilots Juan Pantoja Arriaga and Juan Martínez Zayas sailed the entire coast of the Strait of Nutka aboard the corvette Nuestra Señora de Aránzazu. Caamaño was Francisco de Eliza’s brother-in-law and had already participated in an expedition to the Pacific Northwest in 1790; in his 1792 expedition, he would carry out a brief reconnaissance of the Entrada de Bucareli. From there he would go east, near the vicinity of San Bartolomé, to the Punta de San Félix and the ports of Santa Cruz, Dolores, Refugio and La Estrella. Caamaño would return again west towards the northern coasts of the Reina Carlota Islands. Although by then much of that coast had already been explored by navigators from other European powers, and they had already had contacts with the Natives, there were still many places that Caamaño discovered and named in the area and that have survived to this day like the Paso de Caamaño and the Zayas Islands.

In this expedition, cartographic and geographic studies of great precision were carried out, and it also gave rise to an interesting diary, written by Caamaño, in which he detailed both his journey as well as some news of the inhabitants of the Entrada de Bucareli, the Tlingit. He noted, for example, that women:

(…) adorn themselves with five iron rings, four narrow ones that they wear on the wrists and near the ankles, and one large and of wide diameter with respect to the neck on which they place it. They are also hung from the septum of the nose, which is pierced like the ears, a copper or mother-of-pearl crescent from the Monterrey shells, of which they wear other pieces. The inconvenience of the weight of the rings, nor the sacrifice of piercing the nose and ears, dispenses them from the ugliest of dressings in the eyes of a European (…).

Caamaño also pointed out that these women, as well as those in the port of Floridablanca and the ones near the San Roque spout, used a tablet on their lips.[1]

New expedition of Francisco de Eliza

In 1793 Eliza, on board the schooner Activa, accompanied the schooner Mexicana, piloted by Juan Martínez Zayas, in its reconnaissance of the coast between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Bay of San Francisco. Both schooners left the port of San Blas, but soon they got separated. Eliza encountered great difficulties, and was forced to separate from the Mexicana, landed on the coast at a little higher than 43 degrees, and then descended to the ports of La Trinidad (Trinidad, in Yurok territory, California) and La Bodega (Bodega Bay in territory of the coastal Miwoks). Martínez Zayas did manage to reach the Port of Núñez Gaona, at the latitude of 48 degrees. Then he crossed the strait to the port of San Juan, and from there began to sail south along the coasts of Washington and Oregon, and even explored the mouth of the Columbia River (known as Wimahl or ‘Great River’ by the Chinook who lived around its lower course). This trip led to the elaboration of various maps and a spherical chart that represents the coast between the southern tip of Tutasi, in the southern mouth of the Strait of Fuca, and the port of San Francisco.[2] Eliza and Zayas were the last Hispanic explorers to draw up valuable cartographic maps of the region.[3]

In February 1793, the Second Convention of Nootka was signed, for which John Meares was compensated financially for the capture of his ships in 1790 by Martínez. On January 11th, 1794, in lieu of the remaining unsolved issues from the Treaty of 1790, a third Convention was signed, in which the British and Spanish governments established to allow the trade of both nations in the region, to call for the abandonment by the Spaniards of the San Miguel fort, and that neither of the two powers would henceforth build establishments of a permanent nature in that region. Meanwhile, the Nootka garrison had suffered continuous casualties due to desertions, evacuations to Mexico, disease, and cold. At its most populated, it had just over 70 men; by 1793 there were only 59 from the Voluntarios de Cataluña, and this company was relieved by 20 men from the Compañía Fija de San Blas, which remained in the fort until March 1795.

A year earlier, in 1794, José Manuel de Álava was appointed as the new commissioner for the affairs of Nootka, and Salvador Fidalgo would accompany him there with the frigate Princesa. But as the English did not arrive, they retired for the winter to the Port of Monterrey. Finally, in 1795 the English commissioner arrived at the port of San Blas, from where he traveled to Monterrey and then to Nootka to sign the agreed treaties. As both commissioners returned to the port of San Blas, Nootka’s last Hispanic commander, Ramón Saavedra, began to dismantle the Spanish buildings in order to prevent them from being used by others, and he embarked his artillery and his men to leave for the south. They were relieved in June 1794 by a squad of 19 soldiers, under the command of Second Sergeant Francisco Virueta, detached from the Compañía Fija del Puerto de San Blas. The service of the 19 men of this company in Nootka ended on March 23rd, 1795 when they returned to New Spain and left that bay to its original inhabitants, Chief Macuina and his people, thus putting an end to the Hispanic presence in the region.

The Compañía Fija del Puerto de San Blas

Regarding the Compañía Fija del Puerto de San Blas, to which the last men who remained in Nootka belonged, we must remember that Hispanic authorities had understood since 1768, the year of its foundation, the importance of the Port of San Blas. The port was a strategic point to promote expeditions and trade in the northwest of New Spain and even with Asia, as well as to protect the coasts of the viceroyalty and stop pirate expeditions. However, there was a continuous lack of personnel at the port, caused mainly by the territory’s difficulties with very adverse climatic conditions, and by the active participation of its soldiers in the Californias colonization and defense efforts, as well as by the expedition navigations to the Pacific Northwest. In response, in 1787, the viceroy Manuel Antonio Flores mandated that the Compañía Fija del Puerto de San Blas be formed. Initially, this company was made up of 76 men who would reinforce the San Blas Naval Department in terms of its garrison (30 soldiers), colonization missions, and exploration trips to the north. In the Regulations of the Compañia Fija, the shortage of Spaniards to form it was already expressed, and so it was established that it would be made up “of voluntary people accustomed to that climate”; moreover, it was emphasized in said Regulations that “the people who serve in this Company should be from the same [Pacific] coast because they know their terrain well and are habituated to their harmful temperaments (…).”[4] For this reason, indistinctly Spanish, mestizo and pardos[5] were admitted.”[6] In 1792 Viceroy Revillagigedo expressed the need to increase the number of men of the Company by 10. In February 1797, when the last men who remained in Nutka belonging to this Company had already returned, the commander of the San Blas Naval Department, Francisco de Eliza, passed in review of the Compañía de Infantería Veterana y Fija de San Blas. Eliza noted that of its legitimate endowment, which was 105 soldiers, 86 occupied their posts, and of them only two were soldiers from Old Spain (one from Castile and one from Andalusia), while the remaining 84 were from New Spain.

last trip to nutka

As the historian and archivist Alicia Paz Herreros Cepeda indicates, although Fort San Miguel was dismantled and the last Hispanic soldiers left the territory, the then Viceroy of New Spain, Miguel de la Grúa Talamanca, Marquis of Branciforte, ordered that every six months a trip be made from Mexico to Nutka. The purpose of these trips was not only to maintain the Hispanic presence in the area, but to make it clear to both the Russians and the British that the Nutka Conventions did not imply a total renunciation of the Hispanic Monarchy regarding its interests in the region.[7] However, the reality of the available resources and the circumstances prevailed, and only one of those trips was made, in 1796, more symbolic and testimonial than practical, and after it there was no longer any activity on the coasts located in northern California ordered by Hispanic political authorities.

Author’s note ABOUT IMAGINARY OR APOCRYPHAL EXPEDITIONS

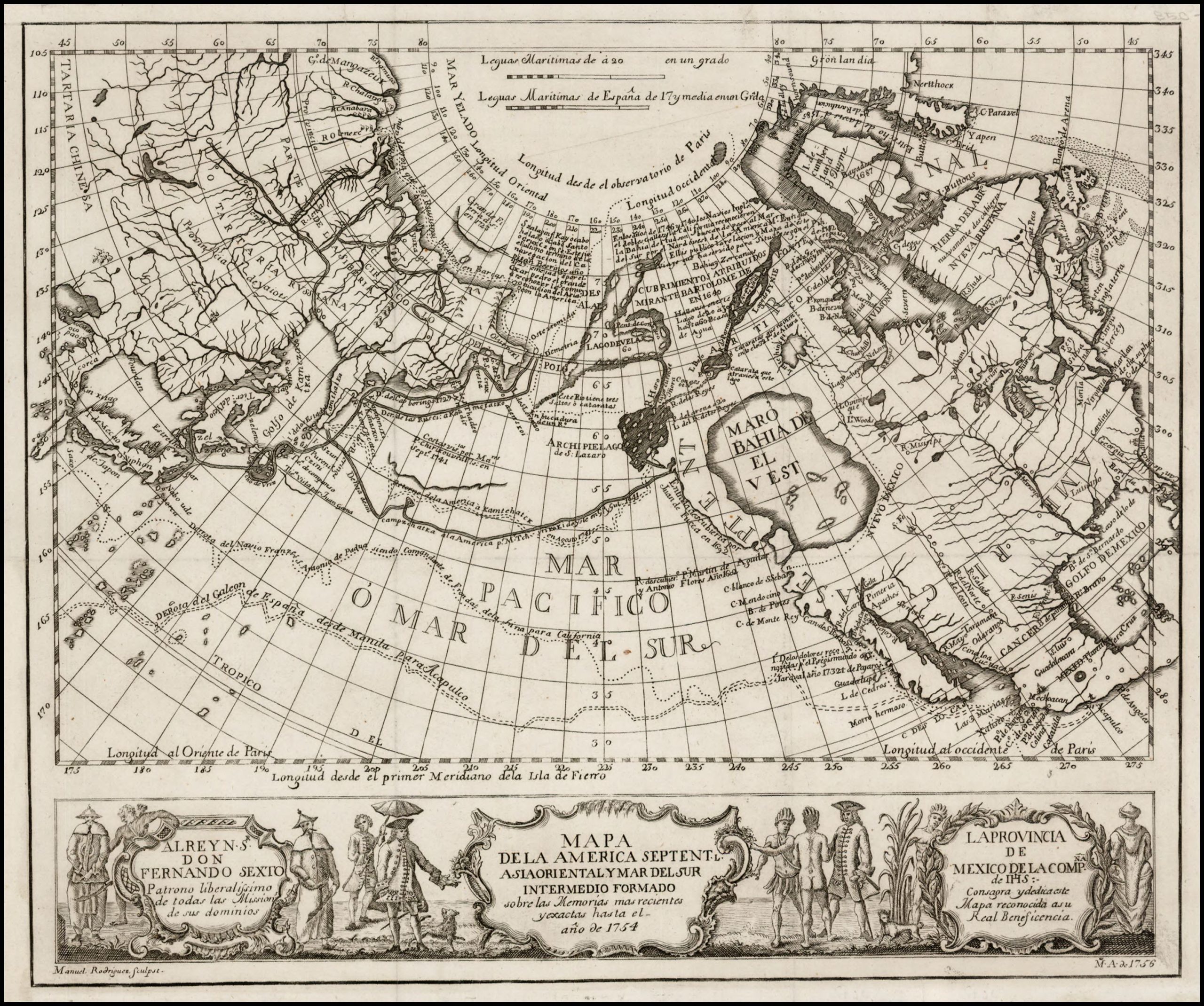

On the imaginary expeditions or apocryphal journeys of Captain Lorenzo Ferrer Maldonado (1588), Juan de Fuca (1592) and Admiral Bartolomé Fonte (1640) and their searches for the Northwest Passage, it is necessary to say that, although for a long time they were given considerable importance, there have been several naval officers and scholars who have carried out inquiries and investigations into them to be able to confirm that the three expeditions were rather imaginary and deceptive. They responded fundamentally to individual interests and they were nothing but the result of entanglements and fables based on confusing news, unspecified dates and geographical inaccuracies. In this historical approach, we have limited ourselves to studying the trips that are well documented, and as we have not found any trace of these three expeditions in the documentation consulted, and their veracity has never been established, we have not considered them of interest in our study. However, we do not want to stop pointing out that the references of these trips that appear in Spanish cartography are mainly due to the fact that these non-verified expeditions were collected on the maps of the French, and on those of the English and the Russians. Interestingly, when the Jesuit Marcos Burriel reviewed the maps of the fellow Jesuit Miguel Venegas in 1750, he had to add more recent geographic information to them, thus, although Burriel himself classified these trips as absurd, his engraver, Manuel Rodríguez, saw himself in the obligation to refer to them in the Mapa de la América Septentrional,[8] published in 1754, as these trips were included in the maps prepared by foreign geographers and cartographers (such as those of the French Guillaume Delisle and Philippe Buache).

We would also like to emphasize the impossibility of collecting in this study all the names of those people who participated, in one way or another, in the trips made along the Northwest Coast of the American continent, as well as those of most of the geographical accidents that they observed and named, the places where they landed, the Native peoples they observed or with whom they had some type of contact, and all the events that occurred during those trips. In order to collect all the information necessary, in addition to many more means and time for study and research, to publish a larger book, much more voluminous, than this study. This work basically attempts to be an approach or approximation, mainly through fragments or extracts from historical texts, to some of the events that happened over several centuries, from the first discoveries on the California coasts and the continuous search for the Northwest Passage, until the Pacific Northwest stopped being a space under the dominion of the Hispanic monarchy to becoming a more cosmopolitan space.

FIGURE 13. Mapa de la America Septentrional, Asia oriental y Mar del sur, intermedio formado sobre las Memorias más recientes y exactas, hasta el año de 1754.[9] Published in 1756 in Jesuit Miguel Vengas’ Noticia de la California, y de su conquista temporal y espiritual hasta el tiempo presente.[10]

- The original of this Diary is in Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City; it is printed in CODOIN, 1849-95, volume 15, pp. 323-63. ↵

- AHN, Estado MPD, 32 to 36. ↵

- His Diaries are in the Archivo General de la Marina "Don Álvaro de Bazá", AGM, Histórico, legajo 4827, oficiales de guerra, legajo 620/355 expediente de Eliza; y Pilotos, legajo 3389/30, expediente de Martínez y Zayas. ↵

- MECD, AGS, SGU, Legajo 7035, 18. ↵

- Literally, ‘brown people,’ presumably Mexicanized Native Americans. ↵

- MECD, AGS, SGU, Legajo 7035, 18. ↵

- Herreros Cepeda, Alicia. “Breve introducción a la presencia española en el Noroeste de América,” in the Actas, Ponencias y Comunicaciones Presentadas en el Congreso El Ejército y la Armada en el Noroeste de América: Nootka y su tiempo, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, 2011. ´[Brief introduction to the Spanish presence in the Northwest of America ] ↵

- [Map of North America]. ↵

- John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Accession Number 01559. // [Map of North America, Oriental Asia and the South Sea Intermediate, Formed On the More Recent and Exact Memories, up Until the Year of 1754]. ↵

- [News of California and of its Temporal and Spiritual Conquest up Until Present Time]. ↵