3 First Half of the 17th Century

Second Expedition of Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno’s second trip emphasized the geographical exploration of the coasts, rather than being commercial in nature. This change was due to the growing threat from England and other European nations, who were not only trying to find a navigational route to the East, but also to dispute Hispanic maritime hegemony in the Pacific. Now the royal instructions were different, and in this expedition military experts, navigators and cosmographers, such as Gerónimo Martín Palacios, would be included. The instructions were clear: the main objective of the trip would be “the discovery and demarcation of the ports, bays and inlets that exist from Cabo San Lucas, which is at 22 and a quarter degrees latitude, to Cape Mendocino which is at 42 degrees.”[1] It was also established that the expedition members would not enter any inland port in search of indigenous people, not even to know if there were any, since this was not the main objective.

This exploratory venture produced a large amount of documentation. Among the documents found were the instructions given to Vizcaíno in 1602, and also the minutes of the meetings held by the captains, pilots and the cosmographer.[2] A brief yet complete descriptive account by Fray Antonio de la Ascensión, peppered with his opinions regarding everything that happened during the expedition, was found as well.[3]

According to this document, the Relazión del viaje y derrotero de las naos que fueron al descubrimiento del puerto de Acapulco a cargo del general Sebastián Bizcaíno,[4]dated in Mexico in 1602, Vizcaíno’s ships left the port of Acapulco on May 5th 1602, with the order to reach Cape Mendocino.[5]The expedition consisted of the San Diego, which was the flagship, the Almirante Santo Tomás ship, the Tres Reyes frigate, and a nameless barcolongo.[6] On May 19th, all the ships were in the Puerto de Navidad and the next day they set sail for the islands of Mazatlán, where they arrived on June 2nd. They sighted the tip of Baja California on June 9th and two days later they anchored in a bay that they called San Bernabé (now San José del Cabo, at the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula), where they jumped ashore and had an encounter with the native Pericú, with whom they exchanged gifts. The expedition members remained there until July 5th. During that time they tried up to five different times to set sail but due to the contrary winds they were unsuccessful.

The Guaycura, the Yuman, and the Pa Ipai

The expedition then set course for Cape San Lucas, and although the next day the Tres Reyes frigate left, the rest of the ships continued sailing “until they entered a very large bay where they leapt ashore and celebrated mass. They named it Bay of Magdalena” because of the day they arrived there, and perhaps also in tribute to the captain’s wife’s name.[7] The expedition members remained for a few days, during which they contacted local Natives and received news of the arrival of the Tres Reyes frigate. The Natives whom they interacted with were the Guaycura, neighbors of the Pericú, who had already had sporadic contact with the Vizcaíno expedition of 1596. Their peaceful encounter led to changing the name where the meeting took place from Bahía de la Cruz to Bahía de la Paz.

From there the Vizcaíno expedition continued sailing northward, reconnoitering and discovering several different bays, islands, and coves to which they gave names, such as the bay of Santa Marta, the islet of Asunción, the island of San Roque, and the port of San Bartolomé. From this last port the Vizcaíno expedition left on August 23rd to continue their journey toward the island of Cedros/Serros. From there they hoisted sails on September 9th progressing to what they called the Island of San Gerónimo. Later they headed to the Bay of San Francisco, where they again had contact with groups of native Yuman. The crew managed to understand the Yuman and others living in the cove of Once Mil Vírgenes (bay of Saint Quintin; previously the port of Posesión) through gestures. In that way, these people, who were possibly the Paipai, told them “that on the inland there were many Indians that were armed with arrows. They wore Mexican-styled cloaks of animal skins with a knot on the right shoulder, rough leather sandals, and cotton thread.”[8] From there the expedition members continued sailing to what they called the island of San Marcos. At a latitude of about 32 degrees and 9 leagues leeward, they had to dock to get fresh water. While staying in a cove, they again had contact with the native Yuman, although this time it was not a friendly encounter as the expedition was received with arrows and stones. The account was recorded in their journal:

(…) and although from our part they were given the understanding of us not going to harm them but to take water, and despite giving them sponge cake and other things, the Indians did not pay attention to what they were given, what they wanted was to interfere with us getting the water and taking away the jugs and barrels, so they forced three arquebuses to be fired at them, which with the noise of gunpowder and that some tears hit some in the dead works (of the ships) they fled while shouting in despair, and after two hours, a lot of Indians came back, gathering from different ranches, having gatherings together, apparently of what they wanted to do, and thus with an armed hand they came towards us. Seeming as a minor threat with their children and wives and bows and arrows, the said Ensign Pascual de Alarcón came out to greet them, telling them through signs to calm down and be friends; the said Indians said yes, as long as the arquebuses were not be fired anymore, to which they much stared; they gave a female dog as hostage and with this the said Indians left very happy to their villages and we gathered our water.[9]

Coastal Encounters with California Natives

The expeditioners gave this bay the name of San Simón y Judas. From there, they continued sailing to an inlet that they called Isla de Todos los Santos. Later, they discovered other islands along a large bay that they called San Diego. They went ashore in San Diego and met again with the Natives of the land, who seemed open to resolving their disagreements after understanding each other through signing. The explorers had camped near Kumiai (or Kumeyaay), part of an indigenous village called Nipaguay, where they celebrated a mass in honor of San Diego de Alcalá.

They again saw Natives about three leagues further north, and although the explorers did not approach them, an old Native woman approached the captain, who received her gladly. He gave her some beads and food, and then the Natives allowed the explorers to visit their villages and learn about their customs. They then traveled to the island of Santa Catalina, in 34 and a half degrees, where they saw many Chumash in canoes. They asked the Chumash to meet at the beach, where they exchanged gifts for food and again celebrated mass, which was attended by more than 150 natives “who were amazed to see the oater and the image of our Lord Jesus Christ.”[10] Six native girls, ranging from eight to ten years old, ventured to the ships while dressed in their traditional shirts, skirts, and necklaces. The sailors exchanged some other gifts with the natives, and were surprised they had dogs similar to those of Castile.

There was a moon eclipse that night, and the following days the members of the expedition departed. Following the Natives’ instructions, they sailed a little further north to a good port where they were received in canoes, exchanged gifts, visited their village, and held mass once again. However, the captain was very surprised when a native pulled out two pieces of Chinese damasks and was informed that the fabric came from people similar to himself, “(…) who brought negroes with them and who came in a ship which had broken at the coast due to the wind, and that the place was further north.”[11] The Natives wanted to show the captain the place of the shipwreck, but contrary winds impeded that task and Vizcaíno had to keep sailing until he reached a zone of many islands, inlets and shallow waters. An ensign, however, did get close to the place of the shipwreck, and he later told Vizcaino that:

There were many natives that using gestures had told him that there were bearded people, dressed like us, and understanding that they were Spaniards, they were sent a ticket, and that eight bearded Indians came to him, dressed in animal skins, and they could not find out more (…).[12]

The Ohlone and the Discovery of Monterey Bay

On December 1st, 1602, the expedition members left the island of Santa Catalina and the port of San Andrés. As the cold winter grew, many people became ill onboard the ship and the medicine supply was diminishing. Along the way they again met native fishermen in canoes on several occasions. The explorers took note that one of the canoes held “four rowing and an old man in the middle singing something like a mitote[13] of the natives of New Spain, while the others replied to him.”[14] They observed the coast and the heavily populated land until, at a latitude of 37 degrees, they saw an inlet with a good port that they named Monterey.

They landed there and celebrated what would be the first mass in northern California. They then once again established contact with native people, this time the Rumsen (whom the Hispanics called Costanos), a group belonging to the Ohlone nation, who had inhabited the area along the coast from San Francisco Bay to the south of Monterey Bay[15] and the Salinas Valley for thousands of years. These people lived on terraces, hills and alluvial plains of the bay. Some researchers affirm that the presence of the Ohlone cultures may have been greater than originally thought. There are suggestions that the Ohlone culture could have been as numerous as the river basins in that territory.

The villages interacted with each other through trade, marriages, ceremonies, and conflict. Linguistically, they were and still are related to the Miwok tribe. This includes the Uti group of the Penutian and the Penutian languages. They were hunters, fishermen and gatherers who, although they inhabited villages of huts, moved temporarily to collect seasonal food

Along with the fish, mollusks and crabs that they obtained from rivers and coastal waters, aquatic migratory birds also made up a large part of their diet. As their subsistence depended largely on the marine environment, they made small boats with reeds with which they used to look for otters, sea lions and whales. Being semi-nomadic peoples, these boats were likely designed to last a single fishing season.

First Arrival to Cape Mendocino

At the port of San Andres, Viscaíno’s men decided that due to a lack of supplies and many ill sailors, the leading ship would return to New Spain. The other two ships would continue sailing to Cape Mendocino. On December 29th, the flagship, well supplied with firewood, water, and brimming with sick passengers, began its return voyage to Acapulco as the remaining ships continued their journeys north.

The cold was so intense that at dawn on New Year’s Day, the expedition members witnessed snow-capped mountains, and the water on board had frozen. However, they continued their travels and reached the cove where the San Agustín ship was lost in 1595; this ship had been sailing from Manila to Acapulco and exploring the coasts of the South Sea under the command of Sebastián Rodríguez Cermeño. The Vizcaíno expedition could not stop due to the contrary winds. The weather was so intense that it caused the disappearance of the frigate.[16] Due to the strong south winds, rain and mist, Vizcaíno and his crew did not manage to reach the Mendocino cape until January 12th. There, they were greeted by a welcoming new moon in the night sky. The winter weather was cold and the waters were rapidly rising. Concerned for their safety, they turned around and decided to return to Cabo San Lucas. The next day the weather settled, and the pilots were able to take it on, and they found themselves at the 41st parallel. Strong winds blew again, and this storm lasted until the 20th day, when they found themselves at 42 degrees:

(…) because the currents and tides led us further to the Anian Strait, we saw that day the mainland as well, from the said cape and beyond, with large groves of pine trees, lots of snow covering the hills that looked like volcanoes. The snow reached the sea, and the twenty first of the month God sent us a little northwest wind, which had been so inopportune to the going but desirable for the return.[17]

They named a mountain they spotted with the name San Sebastian (likely present day Mount Shasta). They then returned to the port of Monterrey and later set sail for Acapulco. On March 21st, they arrived back to Acapulco with many from their crew deceased or dying due to the treacherous journey and illness.

According to the account made by Friar Antonio de la Ascensión, in eight days, they were only able to go up one more degree in longitude, which is 43 degrees. They saw a point they called San Esteban and next to it a river, which they called Santa Inés, and they thought there was the end of the kingdom and of the mainland of California, and the beginning and entrance to the Strait of Anián. Friar Antonio also stated in his account of the travel that he believed the land from the Strait of Anián (the southern part of present-day Oregon) to the city of Guadalajara (in the kingdom of New Galicia) should belong entirely to the kingdom of New Spain, and that the King ought to command the first Spaniards populating the area to pacify and preach the Gospel in the bay of San Bernabé.

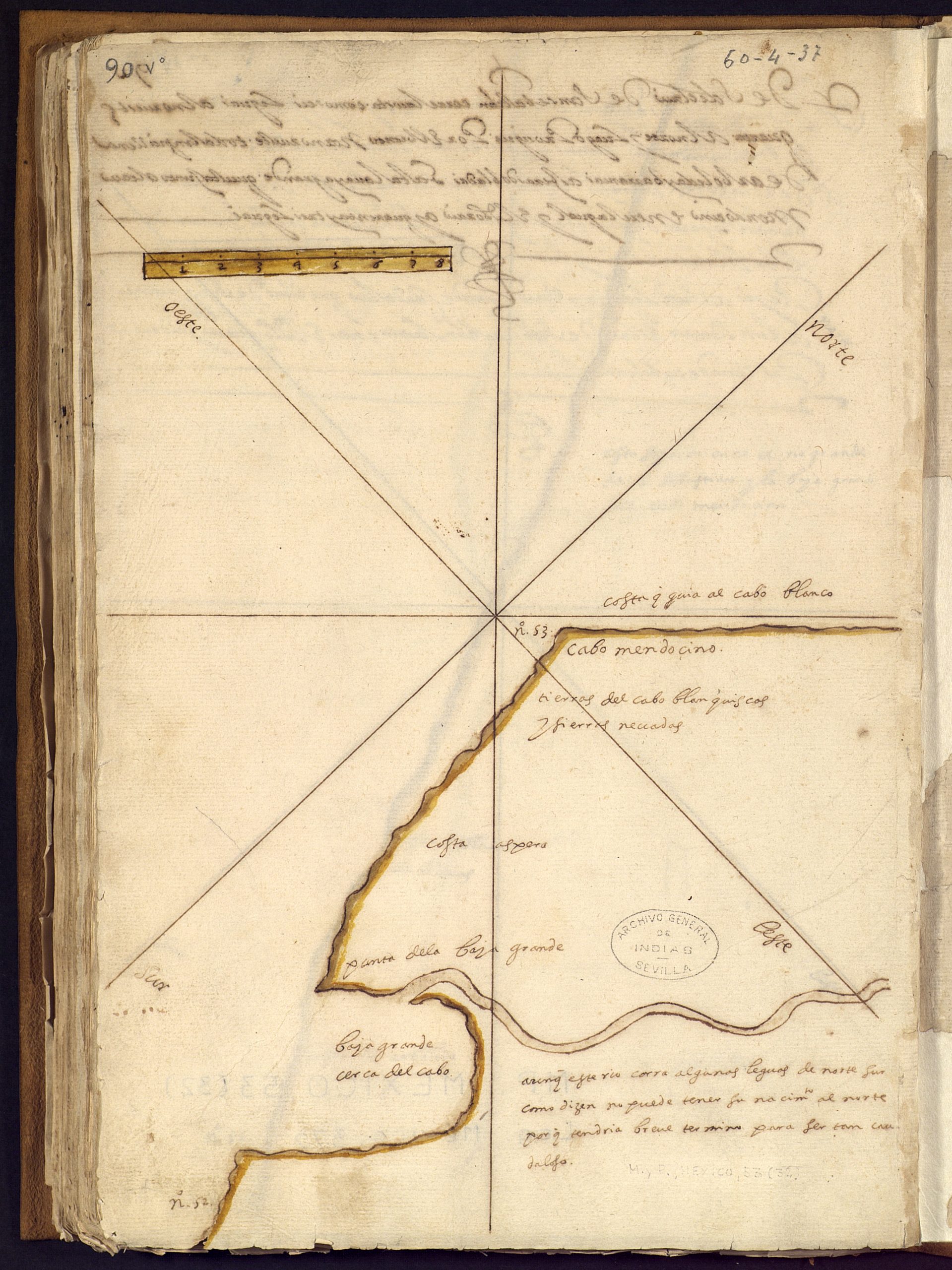

In addition to this account, other captains and helmsmen also described everything that happened on the expedition. Through the work of the cosmographer Martín Palacios, locations were established that were later reproduced by the scientist, Enrico Martínez. These maps were considered to be the most accurate and of the greatest scientific rigor of that time.[18]There were over 30 maps, and they showed the ports, inlets, islands, tips, bays, headlands, and more, that the members of the expedition had discovered. Dr. María Luisa Rodríguez-Sala mentions in her research paper entitled “Sebastián Vizcaíno y Fray Antonio de la Ascensión, una nueva etapa en el reconocimiento de las Californias Novohispanas” that represented one of the initial contributions to regional identity, as cartographic signs are part of the symbolic elements of identity.[19]

Since the cosmographer of the expedition was traveling aboard the leading ship, he did not come to know the coast of the present-day state of Oregon. The detailed maps that Enrico Martínez later elaborated cover only up to Cape Mendocino where he points out that, “that coast guides to Cabo Blanco ( ..).” Only those who were traveling aboard the frigate Tres Reyes were able to observe the coast of the present-day state of Oregon, as they had sailed a little further north than the rest of the ships of the Vizcaíno expedition.

After passing Cape Mendocino, the frigate sailed along the southern coast until finding the mouth of a river leading into the current state of Oregon. Originally, the expedition members called this river the Santa Inés, but it later became known as the Martín Aguilar. However, researchers have been unable to clearly identify which modern day river the explorers were referring to, although they do know it was said to be at a latitude of just over 42 degrees, and the description of the cape could match that of Cape Blanco, which was located at 42 degrees 50.2´N.

There are four rivers that flow to the ocean near Cape Blanco: in the north, the Coquille and the Sixes, and to the south, the Elk and the Rogue. The Sixes and the Elk are more like streams, so their candidacy seems fairly improbable. As for the Coquille and the Rogue, they are of moderate size, which makes them seem nearer to the description made by the explorers. Especially since the storms left heavy rainfall in that area. Their proximity to Cape Blanco is relative since they are much closer to the 43rd parallel, which is why they have been discarded by some researchers.

It is possible that the explorers found themselves in front of Lake Flores, which was located a few miles north of Cape Blanco; they may have mistaken the lake for a river in the accounts of their journey. Another possibility is that the water they spoke of was the Smith or Chetco River alongside the town of Brookings in Coos Bay. Based on the inaccuracy of the latitude observations in the 16th and 17th century, researchers found they were actually located closer to the 41st parallel which could well be the Mad River or Humboldt Bay. The report made by the boatswain stated they could have gone off course as much as 43 degrees and ended up in Cape Blanco by mistake:

(…) since the coast then ran towards the northeast and became so cold that the crew thought things would freeze, the expedition members saw themselves in great danger of getting lost or dying from the miserable situation. Lance corporal Martín de Aguilar and the helmsmen Antón Flores both passed away during this time. The boatswain turned back in search of the main vessel, and at 39.25 degrees, they discovered a mighty river. This river was on an island placed at the mouth of the port, and it seemed safe. There they discovered another great bay at about 40 and a half degrees. Here was another robust river and a large number of Natives rowing out in their canoes. Again, there was a lack of communication between the Natives and the explorers.[20]

The quest of exploration continued to Monterrey. From Monterrey, they ventured to the island of Santa Catalina, the port of Santiago and the port of Navidad, to which they arrived on February 26th.

FIGURE 2. Demarcaciones de la costa occidental de la Nueva España desde el puerto de la Navidad hasta el cabo Mendocino, trazadas por Enrico Martínez, a partir de la exploración de la costa y puertos de la Mar del Sur hecha por Sebastián Vizcaíno en 1602.[21] [The first time that the coast from Cape Mendocino to the south of the future Territory of Oregon is indicated on a map].

FIGURE 2. Demarcaciones de la costa occidental de la Nueva España desde el puerto de la Navidad hasta el cabo Mendocino, trazadas por Enrico Martínez, a partir de la exploración de la costa y puertos de la Mar del Sur hecha por Sebastián Vizcaíno en 1602.[21] [The first time that the coast from Cape Mendocino to the south of the future Territory of Oregon is indicated on a map].

Beginnings of Hispanic Presence in Oregon

Assuming the voyage reached the coastal area of southern Oregon, including Cape Blanco or Port Orford area, the crewmen aboard the frigate Tres Reyes must have observed Natives belonging to the indigenous linguistic group known as the Athabascan languages. The general term ‘Athabascan’ was given by an ethnologist named Albert Gallatin. This was covered in his 1836 classification of the North American languages. Athabascan comes from the Algonquian language, which was designated from Lake Athabasca (in Canada), and still persists within linguistics and anthropology today.[22]

Although several linguistic groups existed in the state of Oregon, the inhabitants of the southern coastal territories were Athabascan, people with access to abundant marine and terrestrial resources. Their territories extended from north of Port Orford to the estuary of the Klamath River in California, where the Tolowas lived. Thus, there were many villages and tribes that made up the Athabascan culture thus constituting a mixture of various Amerindian cultures.[23]

Presumed Route of the Martin De Aguilar ship

According to the different accounts of the time, the ship in which Martín de Aguilar was traveling on, reached a place located between Northern California and Southern Oregon; this could be one of the following geographical points:

- Coquille River, called Ko-kwel (flows into 43º07´25´´N), and which is really a stream whose hydrographic basin is located between the Coos River to the north and the Rogue River to the south. Here lived the Coos Indians of the current Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua Indians, and Siuslaw Indians.

- Rogue River, called Yan-Shuu-chit’taa-ghii ~ -li ~ ‘ in the Tolowa language (flows into 42º25´21´´N), is the place where the Rogue Indians lived, the current Confederated Tribes of Siletz. The Coquelle also have their own tribe, the Coquille Indian Nation.

- The Chetco River, called chit taa-ghii-li (flows into 42º02´43´´N), is actually a large stream located in the southwestern part of Oregon, whose basin is protected by the Rogue river. The name of the Chetco, chit-dee-ne, comes from the word cheti which means ‘those who live near the mouth or near the mouth of the stream’ in the Athabascan language.

- Smith River (41º56´10´´N), at the border between California and Oregon. Its inhabitants are the Tolowa, Taa-laa-wa Dee-ni´, a tribe also belonging to the Na-Dené linguistic family located on the coast, which is a federally recognized nation today the Tolowa Dee’ni Nation.

- Humboldt Bay (40º44´43´´N) and Mad River (40º56´31´´N), on the California coast. The Wiyot, in Chetco-Tolowa Wee-át and Yurok weyet, were the only inhabitants around this bay and its surrounding area for thousands of years.

Sebastián Vizcaíno and Carlos Lazcano Sahagún’s travel discoveries

It was after this expedition that Sebastián Vizcaíno modified the toponymy of certain places that were noted by Rodríguez Cabrillo half a century earlier. As the explorer and historian Carlos Lazcano Sahagún writes in his study, “Cómo la California estadounidense llegó a adquirir su nombre,”, even though during these expeditions geographical features such as bays, points, capes, islands, etc. were named, no specific name was given to the greater region.[24] This is already confirmed in the title of the Páez’ report, which, as mentioned earlier, calls the peninsula by the name of California and the zone through which he sailed the Counter-coast of the South Sea or Northern Coasts of the South Sea. Also, in the numerous maps derived from the subsequent navigation carried out by Vizcaíno, the Western Coast of New Spain is named as well as the Coast and Ports of the South Sea, and it is concluded that further north of the latitude that they managed to reach is the coast that leads to Cape Blanco, but beyond that point the land has no generic name.

The reports presented after this second trip by Vizcaíno were so intriguing that the viceroy of New Spain, the Count of Monterrey, and the Spanish Crown itself, all seemed willing to begin the colonization of the Northwest Coast of the American continent. However, the New Spain representative of the Empire died, and his successor, Viceroy Juan de Mendoza y Luna, Marquis of Montesclaros, suspended the project. It was then that all of the attention of the Hispanic authorities was focused on the establishment of permanent commercial relations between the Philippines and Japan. Throughout the 17th century, although exploration trips took place in the California coasts, navigation further north stopped. It wasn’t until the second half of the 18th century when the interest of colonizing northwestern territories on the American continent awoke once again, now with the obvious intention of halting the presence of English and Russian fur traders in that region.

- AGI, Guadalajara 133. ↵

- AGI, México 372 y AGI, MP-México 53. ↵

- Zdenec, J.W., “Fray Antonio de la Ascensión, cronista olvidado de California,” Bulletin Hispanique, vol. 72, num. 3-4, 1970. ↵

- [Relation of the Trip and Course of the Ships that went to the Discovery from the Port of Acapulco in Charge of General Sebastián Vizcaíno]. ↵

- MECD, AGI, C_11154, fols. 0300 to 0392. ↵

- Long and narrow sailing ship. ↵

- AGI, C_11154, folios 0300 to 0392. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. // The female dog was, most likely, given as a gift. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Communal celebration with dancing and drinking, common in ancient and contemporary Mexico. ↵

- AGI, C_11154, folios 0300 to 0392. ↵

- A place known to its native people as Acasta or Hunnnukul. ↵

- AGI México 23, N.50. ↵

- MECD, AGI, C_11154, folios 0300 a 0392. ↵

- AGI, Mapas y Planos-México 53 y Libros-Manuscritos 40. ↵

- Revista Estudios Fronterizos, número 35-36, 1995. [Sebastián Vizcaíno and Fray Antonio de la Ascensión, a New Stage in the Reconnaissance of the Californias of New Spain]. ↵

- MECD, AGI, México 372. ↵

- [Demarcations of the Western Coast of New Spain from The Port of Navidad to Cabo Mendocino, drawn by Enrico Martínez, from the exploration of the coast and ports of the South Sea made by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602]. // AGI, Mapas y Planos-México 53 y Libros-Manuscritos 40. ↵

- In 2012, the annual conference of the Athabascan languages changed its name to the Dené Language Conference. Thus, the Athabascan language is part of the Na-Dené family, one of the largest linguistic groups in North America, second only to the Uto-Aztecan family that extends throughout Mexico. ↵

- In the Pacific group, along the Washington coast and northern California were the Umpqua, Kwalhioqua, Taltushtuntude, Coquille, Tututunne, Chascacosta, Chetco, Hupa, Tolowa, Hoilkut, Tlelding, Sinkyone, Mattole, Kuneste, and Lassik. ↵

- Journal Dvacáté Století, number 1, 2016. // [How the US California Acquired Its Name]. ↵