9 Expedition of Ignacio de Arteaga and Juan de la Bodega y Quadra

All this new geographical knowledge of the Northwest Coast of the Americas made the Spanish Monarchy act to further advance geographical discoveries. They prepared another expedition in 1776 with the goal of reaching 70 degrees latitude. Other goals included continuing discoveries of the Pacific Northwest Coast, evaluating the penetration of Russians in Alaska, finding the sought-after Northwest Passage, and even trying to capture James Cook along those coasts. Hispanic authorities had news of the explorations that Cook had carried out the previous year along the coast of the Pacific Northwest, mainly near the Bay of San Lorenzo, which demonstrated the British’s interest in the area.

This expedition became a reality on February 11th, 1779. Ignacio de Arteaga and Juan de la Bodega, with the frigates Nuestra Señora del Rosario (alias La Princesa) and Nuestra Señora de los Remedios (alias La Favorita), left the Port of San Blas.

Even if the navigation of this expedition was more advantageous and bearable, as it was done with ships superior to those of the previous trips, the first objective was not fully achieved, since Arteaga and De la Bodega managed to travel up the coast a mere 61 degrees. However, throughout the trip they accumulated great information not only of a geographical nature, but also about the ethnography, the flora, and fauna of the coast. De la Bodega, in addition to being a naturalist, was also a kind of ethnographer, and within the documentation written during his expeditions the customs of the Natives of the North American Pacific coast could be studied. Both Arteaga and De la Bodega wrote Navigation Diaries,[1] and, as was customary when the expedition returned, the viceroy of New Spain, the interim Martin de Mayorga, received reports on everything that had happened.[2] As for the other objectives of this trip, namely evaluating the penetration of Russians in Alaska and capturing James Cook along those coasts, could not be achieved as well, since the Spanish expedition did not find any trace of Russian presence nor locate Cook’s ships, since the privateer had died in Hawaii in February of that same year.

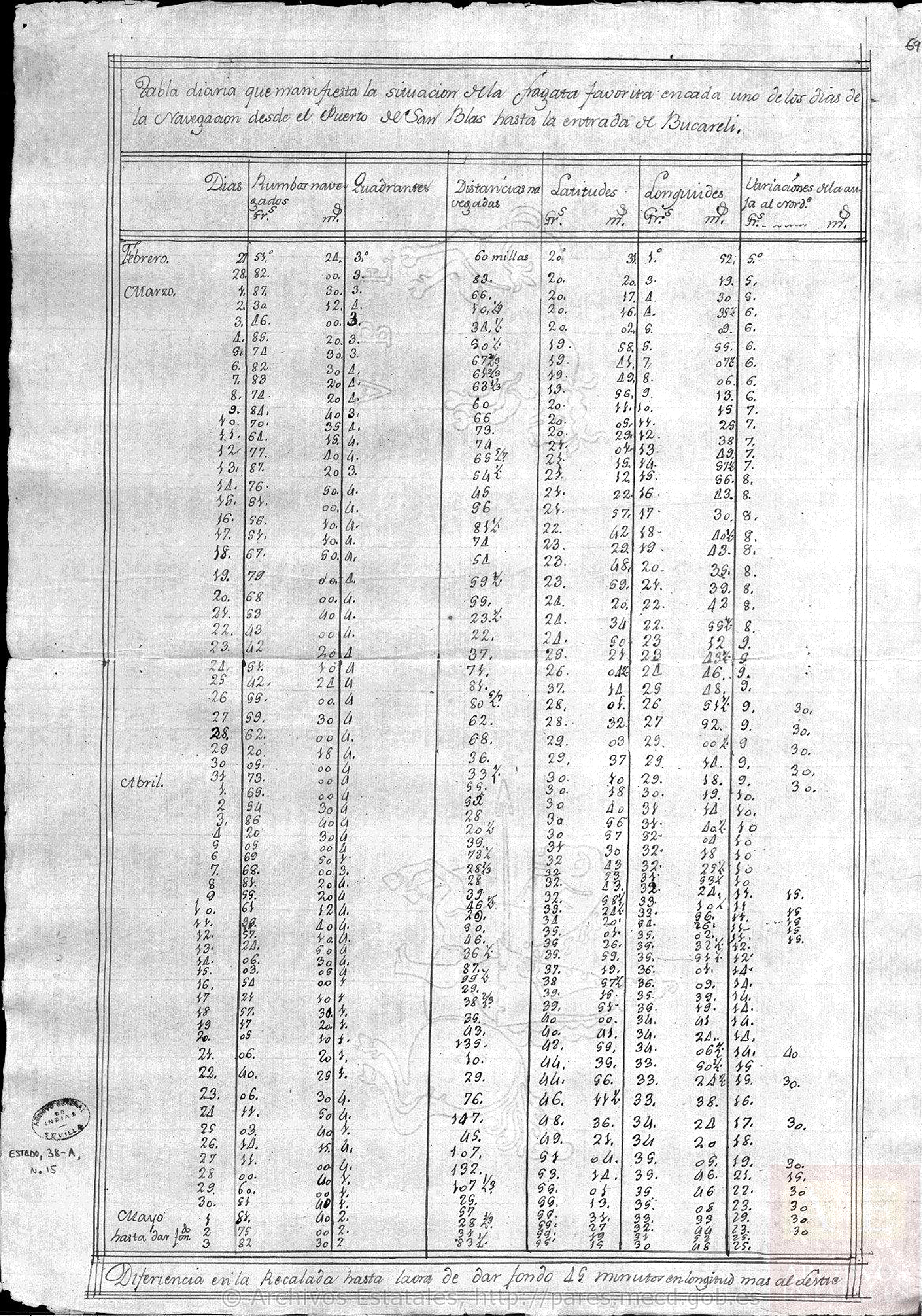

FIGURE 9. Tabla diaria de la situación de la fragata Favorita en cada uno de los días de la navegación desde el puerto de San Blas hasta la Entrada de Bucareli [Copy of the Navigation Diary made by De la Bodega y Quadra, about the explorations on the northern coasts of California from February 11th to the 21st of November 1779].[3]

Arteaga and De la Bodega sailed directly from port San Blas to the Port of Bucareli, located in the Prince of Wales archipelago, at 55 degrees and 18 minutes, where on May 3rd the Favorita sank after 82 days of navigation. At noon the Princesa was discovered, as it had been separated due to a storm on April 20th. However, some wind prevented it from approaching and it was necessary for the ship to continue to a cove located about two leagues to the east, where it found the shelter of a good port in which they secured both frigates to get water and a place to rest for the crew. Once settled they disembarked to formally claim possession of the territory and named it as the Port of La Santísima Cruz, on the west side of Suemez Island (south of the Alaskan archipelago of Alexander; the name of the island surely responds to the last name of the viceroy of New Spain, Juan Vicente de Güemes Padilla), for having discovered it on the day of its celebration, whose festivity was attended by several Tlingit natives, since the entire territory of the Rada de Bucareli was their home.

The Tlingit

The Tlingit were divided into 14 tribal groups, some of them with several villages. Their territories extend from the southeast of the Cooper River in Alaska to the canal of Portland in the current limit of Alaska with British Columbia, an area they had inhabited for more than ten thousand years. Their language belongs to the Kolosh, a group of the Na-dené family and their name means ‘village.’ Their Aleutian neighbors called them Kolosh (Kalohs or Kaluga). Traditionally they have been considered the maximum exponent of the native culture of the Pacific Northwest. They lived in villages of cedar plank houses, which they inhabited permanently during the winter. In front of them they placed totem poles that represented both their ancestors and the social level of their inhabitants. In the summer they moved inland to hunt and fish, supplementing their diet with marine plants, berries, and roots. They built and decorated wooden canoes that could measure up to 20 meters in length and were used for fishing, war (often with their Aleutian enemies), and trade, as their elaborate Chilkat blankets and basketwork were in high demand. In their villages inhabited endogamic clans, whose members descended from a common ancestor, always through the maternal line, and each clan had a chief. They were also organized into lineages, with characteristics similar to clans, the head of which was a chief or warlord, who did not have tribal authority but some lineages seemed to unify the different tribes. Like some of their neighbors, such as the Nootka and the Kwakwaka’wakw, they also practiced the potlatch ceremony.

From the Port of la Cruz, Arteaga’s and De la Bodega’s men left in several boats, commanded by Maurelle and accompanied by the pilots Camacho, Cañizares, and Aguirre, along with some soldiers. They wanted to reconnoiter the surrounding area up to the tip of San Bartolomé. They drew up a map of the port and made a barrack on the beach in which to let the sick men of an epidemic in the Princesa rest. Ultimately, two sailors perished and were buried right there. Natives arrived with fish and pelts that they exchanged with the crew for beads and pieces of iron. They also approached the boats, where they carried out different robberies. Despite such thefts, the expedition members, as noted in the journal of Juan Francisco de la Bodega, “since we wish to treat them with affection to preserve them in a perfect friendship, we paid no attention, and with this pious dissimulation they increased their audacity so they barely reached land without incurring in this offense (…).”[4] It seemed to De la Bodega that the desire they had to get iron and cloth was so great that they even exchanged their own children for it.

While the expedition members continued to explore the coast to the north from the boats, the frigates continued to receive visits from natives, who “under the pretext of their trade did not stop stealing despite more vigilance, sometimes the rings on the side, other times some knives and even the latch that served to secure the royal scale.”[5] The Natives finally indicated to the expeditionaries that they had to leave because that was their port. In the following days there were many who approached them in canoes, around a thousand of them, according to De la Bodega. They also removed the cross that had been placed on the beach and even kidnapped two sailors who had come ashore to wash their clothes in the nearby streams. Then the men of the expedition captured one of the natives. The sailors talked with an elderly native who commanded many of them and promised that they would exchange the prisoners. However, they did not keep this promise, and the Hispanic expeditionaries decided to sink some canoes; they also rushed to capture the Natives who were in them, and even saved some of them from drowning. Although one Native was killed, they finally obtained the exchange of prisoners. As the two sailors confessed to having voluntarily gone with the Natives, they were punished with a hundred lashes each and sentenced to prison for their crime. As for the Natives, it seems that they went to their villages in a somewhat grateful way for having been rescued from the sea when their canoes sank.

On the physiognomy, the way of dressing and the ornaments that the natives used, De la Bodega collected in his journal that:

the color of these people is a light brown and a regular white, and their faces have very good perfections. They are of more than common height, stout, arrogant in spirit, and generally inclined to war. The clothes they wear are limited to one or more wolf, deer, and bear pelts or other animals, which cover them from the shoulders to the knees. Some also showed up with well woven-woolen blankets, one and a half varas long and one wide, with a fringe around half a quarta.[6] Others wore tanned leather boots open in the front that they closed with a cord. They cover their heads with well-woven hats made of some tree bark, the shape of which is the same as that of a funnel. On the wrists they wear copper, iron or whale bone bead bracelets, and on the neck several threads of their beads made of bone and extremely fine copper necklaces. In the ears, wires of the same twisted metal, jet-black beads and some little beads that they make with a certain rubber that looks like topaz. They have long brown hair, which they wear down to the middle from where they make a perfect ponytail to its end with a ribbon of wool. Some days they paint their faces and arms with reddish ocher and lead paint and cover their heads with small feathers of birds that they procure for this purpose.[7]

About the women, De la Bodega pointed out in his journal that they had a pleasant countenance, light color, and rosy cheeks, with hair in a braid, dressed in a kind of leather tunic cinched around the waist and had holes in the lower lip; “they keep increasing this hole until a little round sheave can be placed, thick as a finger, concave on both surfaces and the smallest one of one-inch diameter.”[8]

The expedition members also observed that only married women wore it in this way, while the girls carried a copper pin crossed by the place where they would later stuff said roller and a little shell that passed through the joint of the nose. De la Bodega’s attention was caught by “a herb to which they are very affectionate, and in the Kingdom of Peru they call cochaivio.” The Lima official must surely have been referring to cochayuyo or cachiyuyo, a type of edible seaweed that has been a nutritional source for the native communities of the American continent for centuries.

In addition, he also highlighted that on top of the cliffs grew an abundant and thick undergrowth, “and among them are nettles, chamomile, wild celery, anise, plantain, celandine, elderberry, wormwood, and sorrel.” Something that also caught his attention were the characteristics of Tlingit defensive weaponry, as well as their offensive weapons and the use of copper and iron, the first generally for decoration and the second, surely obtained from other vessels for the blades of their knives.

Sánchez Montañéz has also studied this expedition, analyzing its various diaries and reports, trying to document through their description the various objects exchanged with the natives and now kept in the Museum of the Americas in Madrid (shirts, caps, necklaces, maces, etc.), and writing in her study that the delivery of children points to the first ethnohistorical evidence of the slave element, of great importance in the traditional culture on the Northwest Coast.

On June 15th, the expedition members set sail to the port of San Antonio, from which they tried to leave on the 18th without success, due to contrary winds. Engaging in contact and commerce with the Tlingit, once more. On July 1st they managed to leave the port; after eight days of sailing they found themselves at 58 degrees and 6 minutes. On the 15th they continued sailing towards the northwest. The expedition party recognized a cape that Russian explorer Vitus Bering called San Elias in 1741, which they now called Santa Rosa. When they passed Santa Rosa at 59 degrees and 52 minutes, they anchored at about 14 leagues from the coast after seeing some natives in canoes signaling them. They named what is currently known as Kayak Island Nuestra Señora del Carmen (first named Kayak by the Russians in 1826 because of its resemblance to the outline of this type of canoe, but baptized in 1778 by James Cook with the name Kaye Island).

The Eyak and Chugach peoples

At that time the territory up to the southernmost islands of the Prince William Cove, between the mouth of the Cooper River and the mountains of San Elias, was inhabited by the Eyak. This tribe called itself Unalakmiut, a name that comes from the Eskimo language Chugach Iiyiaraq or Igya’aq, which means ‘neck,’ and refers to the shape of the river in the area where they lived. Eyak has been the first Alaskan language to become extinct in recent history, being a close relative of the Athabaskan languages. The Eyak people lived fundamentally from salmon fishing and, even though they are found within the cultural area of the northwest tribes, they showed a strong Aleut and Inuit influence.

FIGURE 10. Carta reducida de las Costas y Mares Septentrionales de Californias formada hasta el grado 58 de latitud por las observaciones hechas por el Teniente de Navío Don Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra y el Alférez de Fragata Don Francisco Antonio Mourelle, cuya costa se representa por medio de sombras de tinta y cuanto se manifiesta por la sombra encarnada pertenece a la de Monsieur Bellin. Impresa el año de 1766 . [A map of the Pacific Northwest Coast from Cape San Lucas to the 71 degrees north latitude].[9]

It appears that the island named Del Carmen was the first place where the expeditionaries saw the type of boat or canoe from Eskimo origin, concretely Inuit, called kayak. From there, they sent a boat so it could reconnoiter the coast and they prepared to claim possession of the cove near the anchorage (present-day Prince William’s Cove, whose Tlingit name is Chágugeeyí, meaning ‘great bay’) and it was named Port of Santiago (current Port Etches, next to Magdalena Island or Hinchinbrook Island). They were at a latitude of 61 degrees, in Arctic territory, reaching the northernmost point on the North Pacific coast, and both those in the frigate and those in the boat came across native canoes. They were very likely Chugach Natives, whose name comes from the term Cuungaaciiq, the name of the northern mountain ranges that make up the Pacific coastal chain in the extreme western part of North America. They inhabited these territories for thousands of years, specifically the region of the Kenai Peninsula and Prince William’s Cove.

The Chugach are Aleut or Alutiiq people, a name that was given to the natives of that region by the Russian settlers and fur traders, although they call themselves Sugpiat which means ‘royal people.’ Within the Sugpiat the Chugach have always spoken their own dialect, Koniag, though it comes from the Alutiiq language, also called the Pacific Yupik or Sugpiaq, which is a branch of the Alaskan Yupik that extends throughout the southern coast and belongs to a group of Eskimo-Aleut languages. Their people always lived near the coast in semi-subterranean houses called ciqlluaq, taking advantage of the maritime resources for their subsistence, as well as gathering berries and hunting some terrestrial mammals. De la Bodega noted in his journal that:

The clothing[s] they wear is a full fur tunic that covers them sufficiently, their hats are like those of Bucareli, necklaces made of thick glass beads and even though we urged them to tell us who they had obtained them from, it was not possible to understand, but they did tell us with clear enough gestures that they had seen other larger ships enter through the part from where we were (…) their language seemed to us a very confusing jargon without mixture with another language. Their nature is sweet and peaceful, and that they lived with each other in harmony.[10]

Last Stage of the Arteaga and De la Bodega expedition

While Cañizares and Pantoja explored the coast in a boat, they observed a wall of mountains from east to north (the Chugach mountains), which made Arteaga think that behind that cove there could not be a passage to the Northwest, an idea he shared in a meeting with the rest of the officers. Despite this evidence, the expeditionaries continued navigating, and on August 1st, they anchored near the cove they baptized as Nuestra Señora de la Regla (present-day Chatham Port, in Elizabeth Island, near the tip of the Kenai Peninsula), at 59 degrees and 8 minutes, where once again some native canoes approached them, but they were not able to establish any contact with them. They were there for a few days, and occasionally the weather was clear enough that they were able to see Mount Iliamna.

On the 7th of August they set sail with the idea of returning to San Blas. The 22nd the expedition was located at the Entrada de Bucareli, and on September 4th they demarcated the Port of Trinidad, then rounded Cape Mendocino. On the 14th of September after a long journey where they suffered almost continuous bad weather and multiple illnesses, they arrived at the port of San Francisco. It was there where they reunited with the Princesa frigate and received the news of the Spanish King’s declaration of war with England. With the Spanish and English relationships broken, at the Port of San Francisco De la Bodega received the order to go to San Blas, where he arrived on November 21st, 1779.

- AGI, Estado 38A, N.13 y N.15. ↵

- AGI, Estado 20, N.28. ↵

- Ministry of Education Culture and Sports, AGI, State 38A, N.15, image number 137 (folio 69 r). // [Daily Table of the Situation of the Frigate Favorita in Each of the Days of Navigation from the Port of San Blas to the Entrada de Bucareli]. ↵

- Ministry of Education Culture and Sports, AGI, Estado 38A, N.15. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 3 feet (one yard) = 1 vara. A cuarta was often considered as the distance from the tip of the thumb to the pinky of an extended adult hand. ↵

- Ministry of Education Culture and Sports, AGI, State 38A, N.15. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- AGI, MP-México, 359. // [Map of the Coasts and Seas of Northern California Formed up to 58 Degrees Latitude According to the Observations Made by Ship Lieutenant Don Juan Fransisco de la Bodega y Quadra and Frigate Ensign Don Francisco Antonio Mourelle. The Coast Is Represented on the Map Using Ink Shadows and What Is Manifested by The Incarnate Shadow Belongs to that of Monsieur Bellin. Printed in the Year 1766]. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 38A, N.15. ↵