7 The Expedition of Juan José Pérez Hernández

In 1773, it was decided that the viceroy of New Spain, Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, was to order a new expedition. This was decided after the Count of Lacy warned about the possible intention of the Russians to continue their advance from Alaska to the south. The expedition was commanded by the pilot Juan José Pérez Hernández, a frigate lieutenant, who was to explore the Pacific coast up to 60 degrees north, and reaffirm Spanish rights over all such lands in the name of King Carlos III. He was tasked with recognizing and taking possession of all lands discovered and that were not occupied by other nations. He also wanted to evict potential settlements from other rulers, requesting it at first and then, if necessary, doing it by force. For these purposes, Juan Jose Hernández was the pilot whose expedition aboard the frigate Santiago (alias Nueva Galicia) left San Blas on January 24th, 1774 with the first pilot Esteban Jose Martines. The Santiago anchored in the port of San Diego, and later in Monterrey, where the ship was prepared to go sailing on June 6th to higher latitudes.

In Monterrey, the chaplain Fray Juan Crespi and the missionary Fray Tomás de la Peña y Saravia, future authors of meticulous journals in which they described all events during their trip, embarked. This included the first ethnographic observations made by European explorers about the Haida.[1] In addition to these journals we have those of the expedition officers which also collected detailed descriptions of the material culture of the natives with whom they made contact. Also in this expedition, as would often happen with subsequent expeditions, they collected several artifacts that were exchanged with the natives. Today, these are kept in the collections of the Museo de América in Madrid. This subject has been thoroughly studied by archaeologists and anthropologist Ema Sánchez Montañés, who in her article, “The 18th Century Spanish Expeditions to the North Pacific and the Collections of Madrid’s Museo de América,” explains how Pérez Hernández’s expedition made contact for the first time with the Haida and Nuu-chah-nulth Natives.[2]

FIGURE 3. Carta de fray Junípero Serra remitiendo el diario de fray Tomás de la Peña de la expedición de Juan Pérez a California y dando noticias de las misiones, 1774. [First time that Hispanic expeditionaries reached current Oregon’s coast and fully described it at 48 degrees latitude].[3]

The observations of Hernández’s crew on the Haida Tribes

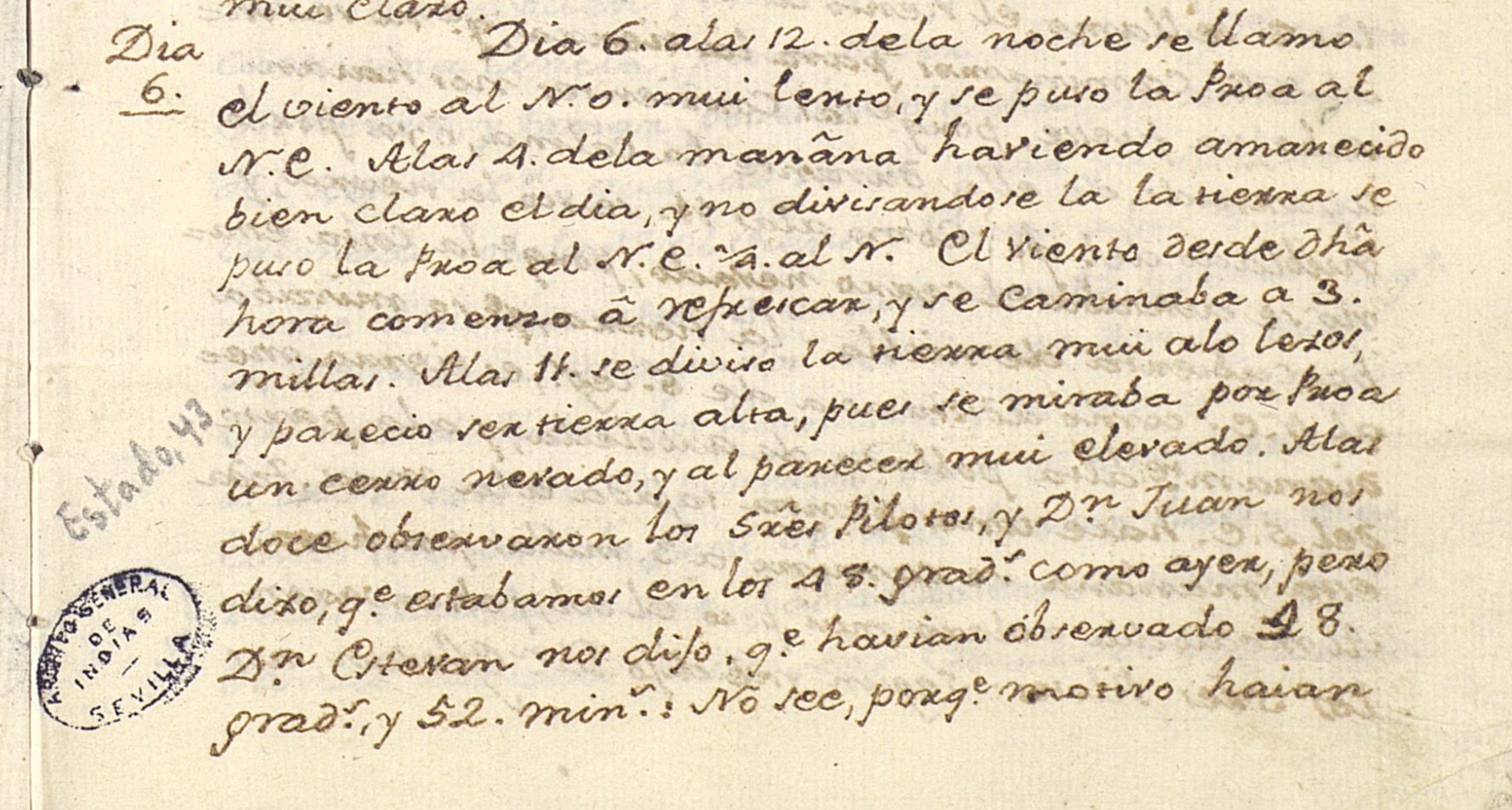

In Fray Tomás de la Peña y Saravia’s navigation journal are the first descriptions of the coast and the inhabitants of the future Territory of Oregon. The religious man tells that the Santiago ship left Monterrey on June 6th, 1774 and that the ship San Antonio, alias El Príncipe, was also accompanying the navigation. After passing the points of Año Nuevo, Pino, Cipreses and the cove of Carmelo, the expedition members spotted the Santa Lucía mountain range and continued sailing. On the 5th of July the pilots warned that they were at a latitude of 43 degrees and 35 minutes. They continued sailing until they reached 55 degrees on July 22nd, without being able to touch land because of bad headwinds. Further north, at 55 degrees and 49 minutes, they reached what they called Santa Margarita (now Point Saint Margaret, at one end of the current entry of Dixon, between the State of Alaska and British Columbia of Canada). Here, they first saw native canoes. Fray Tomás gathered in his journal that:

(…) about 200 souls came in these canoes, in some there were 21 people, 19 in others, yet in others there were 5, 7, 12 and 15 souls. A canoe came with 12 or 13 women without any man; in the others there were also some women, but the largest number were men. By the time they reached our ship the women’s canoe happened to bump its bow in that of another canoe with men in it, which broke the bow, so the men got very angry, and one of them caught in his hands the bow of the women’s canoe and smashed it to pieces, as revenge for their neglect. The canoes stayed all afternoon, there were 21, all around our ship, trading with those on board, for which they brought great precaution of mats, skins of various species of animals and fish, reed hats, fur caps and plumage of various types, and especially many bedspreads or woolen fabrics very embroidered, like a rod and a half, in blocks with its fringes of the same wool around, and various pieces of different colors. Our people bought some of everything for clothing, knives and trinkets, various pieces. It was known that they have a lot of fondness for commerce, and that what they most wanted was things of iron, but they wanted large pieces, and for cutting, like swords, [or] machetes (because by showing them belduques[4] they let us know those were too small), and after we offered them barrel hoops, they showed us they did not cut. Two gentiles got on board and they liked our ship and its things. Women had their lower lip drilled, and a flat rim was hanging on it, which we did not know what it was or what material it was made from. Their dress is a cape with fringes around it and a garment loom of wool or woolen fabrics, or leather, which covers the whole body. They have long braided hair down their backs, they are White and blonde, like any Spaniard, but they are disfigured by a circlet that they have on their lips that hangs down to their chin. The men are also covered with skins and woolen fabrics, and many with capes, like women, but they do not hesitate to remain naked when they see an opportunity to sell their dress. At 6 o’clock canoes said goodbye going to their land, and demonstrated that they wanted us to go to it. Some sailors jumped into the canoes and the gentiles embraced them with excitement and happiness. These gentiles implied that we should not go north because there were bad people who shot arrows and killed (common tale among gentiles, to say that everyone else is bad but not them).[5]

Fray Juan Crespí also made a description in his journal of the Natives they met at a height of 55 degrees, near the tip of Santa Margarita: “these gentiles are stout and heavy-browed, good-looking and white and russet, with long hair and covered with the hides of otters and sea lions, as it seemed to us, and all or most of them wore their well-woven reed hats with a pointed crown.”[6] He also collected that some women paddled alone in the canoes, ruling them like the most skilled men, and added that:

(…) canoes came on board without the slightest misgivings, singing and playing some wooden instruments, like a drum or tambourine, and some with gestures of dancing, they approached the frigate surrounding it on all sides and then a fair opened between them and ours; which then we learned they came to treat and trade their things with others of ours; they were given some bedulques, rags and beads, and they reciprocated by giving leathers of nutrias and other unknown animals, well-tanned and sueded, nutria bedspreads, sewn some pieces with others, that not even the best tailor would do better, other bedspreads or blankets from fine wool or animal hair that looks like fine wool woven and worked from thread of the same hair, of various colors, mainly white, black and yellow, a fabric so dense that it seems to be made on looms. And all the bedspreads have fringes of the same twisted thread around them.[7]

The religious man narrated in his journal that they obtained some fine small carvings from the natives, well-wrought, such as sculptures or figures of men, animals and birds. There were also some spoons made of wood, with adornments on the outside and smooth on the inside, one of them was made of animal horn. They also obtained pine boxes that instead of being nailed were sewn with thread at the four corners, and were somewhat rough on the inside, but on the outside were well carved and smooth. The boxes had carvings with various figures and bouquets of inlaid shells. There were also sea snails in beautiful lace, some painted of various colors, mainly yellow. The boxes served them to store their things and to sit on them to row. Juan Crespí was surprised that the women had their lower lip pierced with a roll painted with color, which according to him made them very ugly, and that “with ease, just by moving the lip this tablet is lifted and covers their mouths, and part of their noses.”[8]

Archival evidence suggests that two of the Natives boarded the ship where Pérez Hernández’s men showed them the chamber and an image of the Virgin; they seemed to admire it, so Pérez Hernández’s men gave it to them. In turn, two men from the expedition jumped into the canoes, and danced with the natives. After this friendly meeting, the expeditionaries tried to approach the ship ashore, but the currents prevented it and they had to continue navigating. Crespí concluded in his journal that the women were very well combed, with long hair in a braid, that they all wore iron and copper rings on their fingers. According to the captain, who had been in Asia for a long time, they closely resembled the Sangley of the Philippines.

Juan Pérez Hernández also wrote a navigation journal from the frigate Santiago, and in it he collected, as a summary, that in 55 degrees latitude:

I found multitudes of Indians who came out to meet me with their canoes, indeed beautiful people, both men and women, being white their color, blond hair, blue and brown eyes, and very docile. According to those who went to the side, [of the ship] there were 21 canoes with up to two hundred and more Indians, not counting two canoes full of women and some small children; they dealt with the crew trading various little things.[9]

Further in his journal, Pérez Hernández recorded a description much more detailed of this encounter near Santa Margarita with the natives, where he indicated that:

(…) men were of good stature of body, well built, with a smiling countenance, beautiful eyes and good face, hair tied and composed like a wig with its tail, some had it tied from behind, those who have beards and mustaches like the gentile Chinese (…), all their trade is reduced to giving animal skins such as sea lions, otters and bears, and they also have some kind of white wool that I do not know from what species of animal it is produced, from it they get beautiful milled wool and weave pretty blankets, of which I collected four; they are not large but well-woven and carved.[10]

Pérez Hernández added to these observations that:

(…) they were all stout and good-looking people in their white color and in their features, most of them with blue eyes; the hair is tied the Spanish way, and some use shoulder straps like soldiers; those who have a beard, wear mustaches. The aforementioned king or captain brings his tambourine and rattle music, and before they arrived they danced and sang, and then they started trading with their hides of otters, wolves and bears, which the crew collected quite a few in exchange for old rags. They also picked up some blankets beautifully woven and manufactured, as it seems to me, on a loom. I picked up some too. I noticed some iron things among them, also in the canoes as cutting instruments, including half a bayonet and a piece of sword. They did not like the belduques and with gestures, asked for long swords or machetes, but at last they picked up some knives that the seafarers gave them in exchange for hides. They brought some wooden boxes to keep their things. I asked them a thousand questions and they did not understand me, not even with gestures. Many of our crewmembers jumped in their canoes and two of them came on board (…) among the 21 canoes came two full of women with some babies in arms and older kids, they were all good-looking, white and blonde. Many of them use their iron and copper bracelets and some headbands of the same; they wear their clothes made of leathers fitted to the body. Their lower lip in the middle they have it drilled, and in it they put a painted shell lip that reaches their noses when they speak, but they have a regular movement, and this is apparently used by married women, because some women did not use it. Both men and women had good body build.[11]

FIGURE 4. Juan Pérez’ Diario de Navegación, 1774. [First reference to the bone earrings of the natives at the Rada de San Lorenzo, at 49 degrees and 5 minutes].[12]

A second pilot of the expedition, Esteban José Martínez, also wrote about what happened on July 20th and 21st, when they met the natives near the tip of Santa Margarita, highlighting that:

(…) what surprised me was seeing half a bayonet, and someone with a piece of sword made knife. This instrument they did not like much and asked for swords, and big knives ( ..) and this land is on 55 degrees and 30 minutes, and it is the same place where the lieutenant of the Captain Bering, Monsieur Tchirikov, lost his boat and people by the same month of July of 1741, and I believe that the iron that these Indians possess comes from the sad remains of the poor people who embarked on said boat.[13]

The Haida

Sánchez Montañés notes in her article that some of the objects then obtained by Pérez Hernández’s men were the first ones gathered by Spaniards in the Pacific Northwest, and specifically in Haida territory.[14] It has been deemed probable that the Haida Tribe came from Dadens, the only important town on the island of Langara. The objects that stood out the most were the “blankets and hats,” but among the pieces from this expedition that are kept in the Museo de América in Madrid stands out a small duckling carved from a sperm whale tooth.[15] The duckling was a small, yet very important work of art that has been widely recognized and studied by specialists. Thus, Steven C. Brown, in his work Native Visions: Evolution in Northwest Coast Art from the 18th through the 20th Century, considers the duckling as the oldest documented piece of art in any collection in the world, as he points out that at the date of its collection, the piece could have already been of considerable age.[16] According to Sánchez Montañés, the carved duckling amulet and other pieces from North America (mostly ones from the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia collected at the end of the 18th century) are testimonies of some peoples that had yet to experience the accelerated changes that conquest and colonization would later bring. The duckling amulet is also the only piece in the collection for which the exact circumstances of its collection in 1774, are known. It was described by Hernández as “(…) a very fine bag of vejuquillo[17] exquisitely carved; and in it a kind of bone bird with the upper beak broken, rescued from an Indian who had it around her neck with a portion of little teeth, apparently from a small caiman.”[18]

FIGURE 5. Haida amulet representing a duck, collected by the expedition of Juan Pérez Hernández in 1774.[19]

The Haida were, and still are, an indigenous nation that has traditionally been included in the group of the Na-Dené languages because of their similarities to Athabaskan-Eyak-Tlingit. Nowadays, though, many linguists consider their dialect to be unique and not related to any of those in the area. They referred to themselves as Xa’ida, which means ‘the town’ or ‘the people,’ and were divided into two groups: the Kaigani (inhabitants of Prince of Wales Island, Alaska, USA) and the Haida (inhabitants of the coastal bays and the entrances to the Queen Charlotte Islands, Haida Gwaii, which means ‘islands of the people’, in British Columbia, Canada).[20] The Haida had developed fishing canoes that could measure up to 18 feet and had the capacity for a crew of 50, and they used them to carry out their commercial activities. These canoes were carved from red cedar wood, the same material in which they sculpted elaborate totems, cedar boxes, masks, and other utilitarian and decorative objects. These were part of the cultural aspects that they shared with their neighbors, the Tsimshian and Tlingit.

Traditionally, each Haida village was an independent political unit and each family in a village was also an independent entity. All the Haida belong to one of two social groups: the eagle or the raven, sometimes referred to as clans, and would marry members of the opposite clan. Clan membership was matrilineal, and each group contained more than 20 lineages. Membership to a clan was publicly proclaimed through an elaborate display of family shields, carved into totem poles that they raised in front of houses, and also carved or painted on canoes.

One of the most important rites of the Haida was the Potlatch (from the Chinook word Patshatl), which encompasses a whole series of festivals that both the Haida and other Native people of the Northwest Coast (Eyak, Tlingit, and Tsimshian) celebrated on designated occasions. Such occasions included the imposition of children’s names, the transmission of privileges, the construction of a home, marriage, and death commemorations. The central aspect of the festivities, as Sánchez Montañés indicates, was the celebration and active participation in the delivery and reception of gifts and was reserved for nobility, although attendance of the ceremonies was widespread.[21] No significant event in the life of a chief could do without the endorsement of the potlatch.

The Haida publicly performed songs and dances that were the exclusive property of the chief. Thus, the potlatch was about ceremonies that functioned to redistribute wealth, confer status, rank individuals, groups of relatives or clans, and resolve claims about names and privileges, as well as rights over hunting and fishing territories. The names of lineages were generally derived from the group’s place of origin. The lineages were proprietary groups and their properties, administered by the chiefs, included rights to certain streams for fishing, hunting sites, places where edible plants existed, as well as cedar, bird colonies, stretches of coastline, and winter village house sites.

The Pérez Hernández Expedition, Continued

Returning to the Pérez Hernández expedition, the ships tried to take on the eastern tip of Santa Margarita the day after their first contact with the natives. They looked for somewhere to anchor, but the currents prevented them from doing so. At noon they measured their position and found it to be at 55 degrees. They then had adverse weather, including thick fog and storm surge, making them lose sight of the point. The friar Tomás de la Peña warned in his journal that the whole Santa Margarita area, and others nearby to the east, were so thick with trees that all that could be seen was a very dense forest of cypress. In the canoes of the gentiles they saw pine, cypress, ash, and beech sticks. Contrary winds forced the navigation course to vary, and the captain decided to call the islands that they saw over the tip of Santa Margarita: Santa Cristina and the other highland demarcated to the northwest, Cape Santa María Magdalena; This was about 10 leagues away. The next day they sailed east and southeast, where they were at 53 degrees and 48 minutes latitude, and at night, “some very luminous resplendence were seen in the sky, to the N. and N.E. part”, surely the first aurora borealis that they could observe.[22] They continued sailing until they saw the Sierra Nevada again, and the friar noted in his journal that:

(…) at the foot of it you can see a high ground that makes a blade at the summit, stretched out from the east to the west, and to the west the land makes a round mogote[23] like an oven, and it appears to be an islet although it could not be recognized if it is, nor if the said high land is part of the continent with the foothills of the Sierra Nevada or an island secluded from it.[24]

That same afternoon a Mexican cabin boy died, named Salvador Antonio. He was a Native American from northern New Spain, married in the Cora town of Huaynamota. The next day they managed to turn to land with the bow to the east; the friar gave mass and gave a burial at sea to the deceased cabin boy. The wind and rain picked up for a whole day, and when the weather cleared, they found themselves at a height of 52 degrees and 59 minutes. From 54 degrees to 52 degrees latitude, all they could observe was very high land, which Hernández decided to call Sierra de San Cristóbal. When they reached 51 degrees, they were able to observe the sun.

The group continually suffered from the rains and bad weather conditions, but got a respite on August 3rd when, at noon, they were at 49 degrees and 24 minutes. Then, by order of the captain, they went east to find the coast; the next day they had not yet managed to see it, but according to the pilots it was very close. At 12 o’clock they observed the sun, while they were at 48 degrees, 52 minutes. On August 5th the expedition was at 48 degrees and the next day they saw a snowy hill, apparently quite tall, still at 48 degrees. These three days were the best of the entire navigation because they were clear and sunny. On the 6th of August it dawned clear, and they finally managed to see land, but it was not until the 8th of August, at 49 degrees and 5 minutes, when at 2 leagues from land they could anchor.

That same day the Natives approached them:

(…) three canoes of the gentiles, 4 men came in one, 3 in another and 2 in the other, they stood a little away from our ship, shouting with gestures for us to leave there, but after a long time, having made signs that they should come close without fear, they approached us and we tried for them to understand that we were going in search of water; but they must not have been very satisfied with our signs and thus they returned to their lands. Upon their retirement they found two other canoes coming towards our boat but having communicated with those who were retreating they returned to the land together with them.[25]

A while later some of the expedition members approached the land by boat, to be able to jump ashore and claim possession of it in the name of the King. At 8 o’clock that same afternoon, three more Native canoes approached them. They were not like the ones they had seen in Santa Margarita, since:

(…) the largest ones will be about eight yards long, they have a long bow and they have a flatter stern, the oars are very beautiful and painted, they form a paddle with a point about a quarta[26] to the end. These canoes appear to be in one piece, although not all of them, as we saw some stitched, but all are very well worked.[27]

It was not until the next day that they finally had contact with the natives; it happened at dawn, before launching the boats into the water to reach land. Then:

(…) 15 canoes arrived in which about a hundred men and some women came. Letting them understand that they should come close without fear, they then approached and began to trade with our people what they brought in their canoes, which was reduced to otter and other animal hides, painted reed hats with a pear on top of them, and woven of a kind of hemp, with their fringes of the same, with which they cover themselves, and most have a cape of this fabric. Our people traded old rags and limpet shells they brought from Monterrey, and some knives for several of their pieces. They showed more fondness for shells. We did not see on these gentiles’ the woolen fabrics, like in Santa Margarita, nor are they as clothed as them. Women do not have small round disks in their lips. Some iron and copper were also seen in these [Natives].[28]

News of the encounter with the Native peoples is also collected in the journal written by Crespí, at a height of 49 degrees and 5 minutes. The friar tells us that they anchored about a league from the coast, and saw canoes arrive, but they soon returned to land. At that point:

(…) the wind stopped completely, and the sea was calm, reserving for the next day to jump on the ground and plant on it the banner of the Holy Cross and take possession of the land in the name of Our Catholic Monarch, may God preserve him. We saw the land well, which was a little bay, named by the Lord Captain the Rada de San Lorenzo, which has a ‘C’ shape. It is a lowland heavily populated with trees, a kind of grove we could not identify. This surgidero[29] has very little shelter from the winds, having two points, one to the Southeast, which was called the Punta de San Esteban, as the second pilot observed, and from this point begins the lowland that is heavily populated with trees and runs in the same way for four or five leagues to the Northeast, which is already highland in relation to where the other point is. This point was called Santa Clara, a saint to whom we are doing her novena,[30] to prepare ourselves for her day. Like a league from the lowland from the said Rada de San Lorenzo, we saw a high mountain range equally populated of trees as the lowland sierra and after the sierra we saw towards the North another higher mountain range, with different peaks covered with snow.[31]

While deep in this Rada, at about eight o’clock at night, the expeditionaries saw the first natives in canoes, who left immediately to return a little later with more. Crespí noted in his journal that:

These canoes are not as big as the ones we saw at Punta de Santa Margarita, since the largest of these would not exceed eight feet, nor are they of the same shape, since they have a long channel bow, and are flatter at the stern. The oars of these are more curious than those of the others, since they are well carved and painted in various colors, and form a palette that ends in a point about a quarta long. Most of these canoes are in one piece, although we also saw some made of well-sewn pieces.[32]

The following day, the expedition members launched the boat into the water to go ashore. At that time they saw 15 canoes leave land with about a hundred men and a few women, then:

(…) the natives were told to lean forward without fear, and they approached and began to trade with our people what they brought in their canoes, that all was reduced to skins of otters and other unknown animals, some painted reed hats, like those at the tip of Santa Margarita, except that in these we saw that the pyramidal cup ends with a ball like a knob, and some fabrics of a thread very similar to hemp, with its fringes the same as its thread. Our people traded them some skins, some of the said textiles, and hats in exchange for clothes, belduques, and limpet shells, which the sailors had collected in the beaches of Monterrey and Carmelo, and we found these great Indians prefered said shells and belduques. Woven wool or hair were not seen in these Indians as in Santa Margarita. On some we saw pieces of iron and copper, and some pieces of knives. We observed that these Indians are also formed like those of Santa Margarita Island, but not covered or dressed like those. These are covered with said skins of otters and other animals, and of said yarn fabrics, and they bring their cape, which is made of tree bark thread. They wear long hair. The women we saw do not have the buckle on their lips as those from Santa’s Margarita do, so they are not as bad looking as those. [33]

As for this meeting with the natives at a latitude of 49 degrees, in the Rada de San Lorenzo, Pérez Hernández also collected in his journal that at first:

(…) in this place we saw many Indian canoes that stood guard at the stern and bow all night, and the next day they came close to us, and they gave us sardines. People also collected some otter and wolf hides in exchange for shells from Monterrey. They are very docile and not so lively as the previous ones, but as white and beautiful as the others; they are also poorer and, apparently, have less ingenuity.[34]

Some lines later he noted that:

(…) the Indians at last came to speak and engaged in their fur trade in exchange of shells that our people brought from Monterrey. They collected several otter hides and lots of sardines. They do not dress like those from Santa Margarita, but with the leathers pulled close to the body. There is copper in their lands, since, we saw several strings like beads that were made of fangs of animals, and at their ends they had sheets of beaten copper, which were known to have been grains taken from the ground, and then mashed, inferring from this there are some mines of this metal. These Nutka Natives are very docile, for they gave their skins before they were paid. They are robust, white as the best Spaniard. The two women I saw are the same, they wear, as well as some other Indians, tendrils made of bone and carried in the ears, and it has been experienced and known that they have not seen people of reason before.[35]

The Nuu-Chach-Nulth

As described in the article by Sánchez Montañés, the expedition members were mapping the outer coast of the Queen Carlota Islands to the south until reaching the Hesquiat Peninsula.[36] At the Peninsula, the frigate Santiago sailed to the southern entrance of the Nootka Strait where trading took place with natives in canoes. The frigate dropped anchor next to an unprotected beach two leagues north of the Punta de San Esteban and four leagues southeast of the tip of Santa Clara. At the time, Pérez Hernández’ men were in the Nuu-chah-nulth territory, for a long time called Nutka or Nootka, but more specifically in Mowachaht territory, Tsitus being the nearest town.

The Nuu-chah-nulth comes from Nuučaan̓uł, which means ‘along the mountains and the sea.’ The people traditionally inhabited the coastal region between Vancouver Island and Nootka Island, spanning throughout the Nootka Strait. From a linguistic and ethnographic point of view they are part of the Wakash peoples, being one of their two main divisions (the other is Kwak’wala). There are at least three recognizable dialects of the Nuučaan̓uɫ language: Northern Nuu-chah-nulth (spoken on the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Brooks Peninsula to Kyuquot Sound), Central Nuu-chah-nulth (spoken from the Kyuquot Strait to the Clayoquot Strait on the west coast of Vancouver Island), and Barkley (spoken in the areas in and around the Barkley Strait, on the west coast of Vancouver Island).

Although the Nuu-chah-nulth shared traditions, languages, and aspects of Wakash culture, they were divided into families or nations. Each nation included several local groups led by a hereditary chief (Ha’wiih), and each group lived off of existing resources within their territories (Ha’houlthee). Groups of hunters traveled in large canoes, establishing temporary camps that allowed them to take advantage of the resources available each season. Red cedar trees were used to build canoes and houses; the roots and bark to make hats, mats, ropes, and other goods. Their society was divided into three classes: nobility, commoners, and slaves. The chiefs, who were part of the nobility, presided over their respective communities and were responsible for making political and economic decisions important to their people. Amongst the families there was a similar hierarchical structure in which the heads of households were responsible for the protection and well-being of their family.

Two more important historical aspects of the Nuu-chah-nulth were their ceremonies, such as the ritual of the wolf, and whaling. Whaling, in addition to being an economic activity, was essential to their culture and spirituality, reflected in legends, surnames, songs and place names. Fernando Monge from the Center for Historical Studies of the CSIC,[37] wrote in his article titled “Mamalnie e indios en Nootka, apuntes para un escenario,”[38] of a native version of the Nuu-chah-nulth history and possible first contact with Hispanic explorers, which was always oral and scarcely known. Monge narrates about a time after Quautz (the Nootka people’s creator god) modeled man from the mucus of the primordial woman; the deer grew antlers on their heads, the dogs tails, and birds wings. Hesquiat natives watched in horror as a massive machine slowly approached their coast. It was a strange floating house with poles and ropes from which human skulls seemed to hang. The elders thought that human corpses composed solely of bones were handling the artifact. Only the bravest did not hide and dared to approach that impressive mass in their canoes. According to Spanish sources, they did not get on board, it seems that they received some gifts from those people who would soon begin to frequent their homes. They called them Mamalni, which in their language means ‘those who live in houses.’ That floating house was likely the frigate Santiago which, in 1774, commanded by Juan Pérez, sighted the entrance to Nootka. The hanging skulls that the natives thought they saw were probably the beams or pulleys of the ship’s mast and sail.

conclusion of the Hernández Expedition

The expedition members were there until August 9th, 1774, bartering with the natives. That day, at about six o’clock in the morning, and with the boat already in the water, the west wind rose and blew them towards the land and forced them to raise the anchor, and get out of danger. However, at dusk, the strong winds and swells carried them towards the coast, so they had to cut the cable and lose the anchor. This meeting with the natives took place in the anchorage which they baptized as the Rada de San Lorenzo (Rada of Nootka on present-day Vancouver Island, a place that four years later Cook would call King George’s Sound). According to captain Pérez, it is at 49 degrees and 30 minutes north latitude. Some hills that are northwest of the Rada were called the Hills of Santa Clara, and the point that is to the southeast was given the name of San Esteban.

Pérez Hernández’ men continued their journey, on the 11t they were able to measure the sun: it was 48 degrees and 9 minutes. They then observed a snowy hill that they called the Cerro de Santa Rosalía (it is possible that they were in front of Mount Rainier, near Portland, whose height of 4,932 meters above sea level makes its peaks usually snowy and whose position of 47 degrees is close to that established by the Pérez Hernández expedition). During the next two days the sun could not be observed, and on the 13th the helmsmen were at 43 degrees and 8 minutes latitude, although it seems that they were not entirely satisfied with that observation. It was on the 14th, in good weather, that they were able to make a better observation and found themselves at 44 degrees and 35 minutes. According to the religious Tomás de la Peña in his journal:

This land has a lot of groves, which in sight looks like pines, not only at the summit but at the foot of the hills. On the beach you can see some elevated lands without groves, with lots of grass and several white ravines sliced to the sea. You can also see some glens which run N.E. to S.W., and in all the land that we saw this day we do not see snow, and to the S. is lower land.[39]

The next day they were already at 42 degrees and 38 minutes. They could not see the coast because of the haze and navigated away from it, although the friar conjectured that:

Cabo Blanco of San Sebastián and that famous deep river called Martín Aguilar and discovered by the frigate of his command in the expedition of General Sebastián Vizcaíno should be there, because although the History says that said Cabo and river are at 43 degrees, according to the observation made by the pilot of the frigate, Antonio Flores, it should be thought that they are at lower latitude, as it has been observed lower with the new octants than the instruments they used in the past.

The expeditionaries continued southward for three days, and on August 20th, they spotted a tip of land that they thought was Cape Mendocino, “and being so the said cape would be at 40 degrees, with a difference of a few minutes (…).”[40] On the 26th they were already near Point Reyes and the port of San Francisco, and on August 27th at 4pm they anchored in the port of San Carlos de Monterrey.

Like friar Tomás de la Peña, friar Juan Crespí also noted in his journal about when the captain observed the latitude of 42 degrees and 38 minutes.

(…) According to these observations and what was reported in the expedition of Sebastian Vizaíno, we conjecture that this is where Cabo Blanco de San Sebastián appears to be, as well as the famous river discovered by Martín de Aguilar , because, although old diaries make it to be at 43 degrees, it has been observed that in the same degrees where these places were then observed, they have now been found to be at a lower latitude thanks to new and more sophisticated instruments; it has been said that the Cabo Blanco and such river must be at a lower height than previously indicated, and so it may be that we are parallel to the said cape, although the fog does not allow us to see the land.[41]

This correction was also confirmed by the observations of Tomás de la Peña once they passed the Mendocino Cape, since “according to his accounts and computations, Cape Mendocino, that is north from us now, is at the latitude of 40 degrees, with a difference of a few minutes.”[42] In fact, captain Pérez Hernández wrote in his navigation journal that “said cape is found at 40 degrees and 8 minutes north and not at the 41 degrees and 45 minutes that Cabrera, Bueno, and Sebastián Vizcaíno situated it.” [43]

Tomás de la Peña ends his journal lamenting not having been able to achieve the main purpose of the expedition, which was:

(…) [to] arrive up to 60 degrees and jump to land and plant in it the Holy Cross; hopefully his Divine Majesty will want that this trip serves at least to move the state of our Catholic Monarch and the Christian zeal of the most excellent Sir Viceroy, so that with the enlightenment that will now be obtained from these coasts, and of the good people that populate it, they will send another expedition again.[44]

In the introduction to his journal, Pérez Hernández also regretted not being able to navigate further north to 60 degrees due to the bad weather experienced, the diseases suffered by the crew, the lack of fresh water, and not having any certainty of a port to reach.

After reading the different diaries resulting from this expedition (both those written by the two religious men: that of the ensign Juan Pérez Hernández, and also that of the second pilot Esteban José Martínez), New Spain’s viceroy Antonio María Bucareli wrote a letter to Julián de Arriaga, Secretary of Navy and Indies, notifying him of everything that had happened during the expedition. This included the contacts established with the natives, the nineteen degrees of height that had been gained, and the knowledge acquired about the non-existence of foreign establishments in those territories. Bucareli wrote in this correspondence that:

(…) the coast and the natives recognized at fifty-five degrees seem to be the same ones the Russians talk about in their explorations of the year forty-one, and that perhaps the remains of the boat that they lost are that part of sword and bayonet that was noticed in one of the canoes in which the gentiles approached on board.[45]

Regarding the natives with whom they contacted at 49 degrees, the viceroy commented that; “they are less unhappy than those of Monterrey, but they do not have, neither in their social relationships, nor in their figure, or in their dress, the advantages of the aforementioned ones.”[46] On his part, Arriaga sent the documentation remitted by Viceroy Bucareli to sailor and cosmographer Vicente Foz y Funes, for him to confirm if these were indeed Russian possessions, since he had had the opportunity to read about the expeditions that the Russians had conducted in the Americas. Most particularly about the expedition of Tchirikov in 1741, in which land was discovered at 55 degrees 36 minutes of latitude and 218 of longitude. After studying all the documentation, Foz y Funes established that:

(…) don Juan Pérez came to discover by 55 degrees and 40 minutes and longitude from the Meridian of Paris of 22 and a half meridian of Paris , from where it can be seen that both arrived at the same latitude, but were merely separated by 3 and a half degrees in longitude, which at that height equals 40 leagues, whose mistake is not significant in any navigation, and much less in this in which the setbacks, rains and lack of vision should induce them in greater a mistake; so there can be no doubt that the two landed in the same place, as confirmed by the half bayonet and the piece of sword that they saw with the Indians, which would undoubtedly have belonged to the ten men who were lost with the boat that Tchirikov sent ashore.[47]

The sailor and cosmographer further established that:

(…) the Russian possessions are 750 leagues away from the Cape of Santa Catalina to the West, and 150 leagues from the last land discovered by Tchirikov, and that in the discoveries that will follow it will not be allowed to pass from 60 degrees, unless a strait is found that separates the land discovered by the Russians from the American continent.[48]

- AGI, Estado 43, N. 9 and N.10 ↵

- “Las expediciones españolas del siglo XVIII al Pacífico Norte y las colecciones del Museo de América de Madrid,” Part of a Research Project titled: Investigación Construcción y Comunicación de identidades en la historia de las Relaciones Internacionales: Dimensiones culturales de las relaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2009-2011. ↵

- Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte, AGI, Estado 43, N.9, image # 35 (folio 16 recto). // [Letter of 1774 by Fray Junípero Sierra, submitting the Diary of friar Tomás de la Peña regarding Juan Pérez’ expedition to California and providing news about the California missions]. ↵

- Large knives. ↵

- AGI, State 43, N.9. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.10. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- AGI, State 38A, N.3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte, AGI, Estado 38A, N.3, image #97 (folio 40r). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Sanchéz Montañés, Op. cit. ↵

- Museo de América de Madrid, Patito, Amuleto Haida, número de inventario 13.042. ↵

- Brown, Steven C., Native Visions: Evolution in Northwest Coast Art from the Eighteenth through the Twentieth Century. The Seattle Art Museum and The University of Washington Press. Seattle, WA & London, UK, 1998. ↵

- Made of vine ↵

- AGI, Estado 38A, N.3. ↵

- Museo de América, Inventario 13042. http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Main. ↵

- They also subdivide into other groups such as the Skidegate and the Masset, these last ones in Howkan, Klinkwan, and Kasaan. ↵

- Sánchez Montañés, Op. cit. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, ↵

- An isolated mound of conic form. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Approximately 21 cm. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Place to anchor. ↵

- Nine days of religious devotions. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.10. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Sánchez Montañés, Op. cit. ↵

- Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas [Spanish National Research Council]. ↵

- Monge, Fernando. Revista de Indias, vol. LIX, num. 216, Instituto de Historia, CSIC, Madrid, 1999. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.10. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 38A, N.3. ↵

- MECD, AGI, Estado 43, N.10. ↵

- AGI, Estado 20, N.1 and N.10, 1773. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵