10.2 Ozone Depletion and Short-Lived Climate Pollutants

Section Goals:

- Review ozone and its protective function in the stratosphere.

- Connect depletion of protective ozone to CFCs.

- Review other atmospheric pollutants that impact global climate and cause net warming.

The Ozone Layer

Ozone (O3) is a gaseous molecule that occurs in different parts of the atmosphere (Figure 1). It is very reactive chemically and is dangerous to plant and animal life when present in the lower portions of the atmosphere. This type of ozone, called ground-level ozone, is a significant hazard to human health and is associated with pollution from vehicle exhaust and other anthropogenic emissions (see section 10.1).

Ozone that occurs in the upper atmosphere is naturally occurring and beneficial to life due to its role in blocking harmful radiation from the sun. This type of ozone is called stratospheric ozone. Ozone in the stratosphere forms when the two oxygen atoms in an O2 molecule are broken apart by the energy of sunlight. Each lone oxygen atom can then combine with a different O2 molecule to form O3, ozone. The ozone layer is the portion of the stratosphere where ozone molecules are present, mixed in among the other gases that comprise the atmosphere (Figure 2).

Radiation from the sun is also called electromagnetic radiation, or simply referred to as light. The sun emits different types of light including but not limited to x-rays, visible light, microwaves, and ultraviolet light. The various types of light are distinguished by their different wavelengths. As wavelength decreases, the amount of energy in that light increases. Ultraviolet light, for example, has shorter wavelengths than visible light and is thus more energetic. Ozone molecules absorb ultraviolet (UV) light, which is advantageous for life on Earth because UV light can break down important biomolecules such as DNA, which can lead to cell death and mutations.

Unfortunately, the ozone layer that protects life on Earth from harmful UV light has been depleted due to human activities. The ozone depletion process begins when CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) and other ozone-depleting substances (ODS) are emitted into the atmosphere. CFCs were used by industry as refrigerants, degreasing solvents, and propellants. In the lower atmosphere, CFC molecules are extremely stable chemically and do not dissolve in rain, and thus can linger for long periods. After several years, ODS molecules eventually reach the ozone layer in the stratosphere, which starts at about 10 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

Once in the stratosphere, CFCs and other ODS destroy ozone molecules. In the case of CFCs, UV light in the stratosphere knocks loose a chlorine atom from the molecule, which can then destroy numerous ozone molecules, as shown in Figure 3.

In effect, ODS are removing ozone faster than it is created by natural processes (as described above), and this leads to a thinning of the ozone layer. This thinning represents a reduction in concentration of ozone molecules in a particular portion of the stratosphere. Areas where the ozone layer has thinned are commonly referred to as holes, although this is not entirely accurate because ozone is still present, it just exists at concentrations much lower than normal.

Policies to Reduce Ozone Destruction

Tackling the issue of ozone layer destruction is an example of global cooperation that produced meaningful action on a large-scale environmental problem. In 1973, scientists first calculated that CFCs could reach the stratosphere and destroy ozone. Based only on their calculations, the United States and most Scandinavian countries banned CFCs in spray cans in 1978.

But more confirmation that CFCs break down ozone was needed before additional action was taken. In 1985, members of the British Antarctic Survey reported that a 50% reduction in the ozone layer had been found over Antarctica in the previous three springs, a very important finding.

Two years after that seminal British Antarctic Survey report, an agreement titled the “Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer” was ratified by nations all over the world. The Montreal Protocol, as it is commonly called, controls the production and emission of 96 chemicals that damage the ozone layer. As a result, CFCs have been mostly phased out since 1995, although they were used in developing nations until 2010. Some of the less hazardous substances will not be phased out until 2030. The Montreal Protocol also requires that wealthier nations donate money to develop technologies that will replace these chemicals.

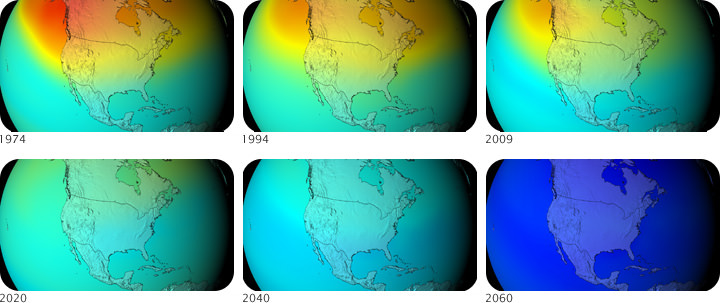

The Montreal Protocol was a success and scientists have found that the ozone layer is recovering and the size of the ozone “holes” are shrinking, thanks to a drastic reduction in emission of ODS like CFCs. The recovery process is slow, however, because CFCs take many years to reach the stratosphere and can survive there a long time before they break down and are rendered harmless. Thus, it will take many more decades for the ozone layer to fully recover.

Constant vigilance and monitoring are needed, however, as illegal production and emission of CFCs and other ODS threaten recovery efforts. In 2018, scientists from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that emissions of a particular type of CFC had increased 25% since 2012. Follow-up studies have since approximated the emissions as originating in particular regions of eastern Asia.

Health and Environmental Effects of Ozone Layer Depletion

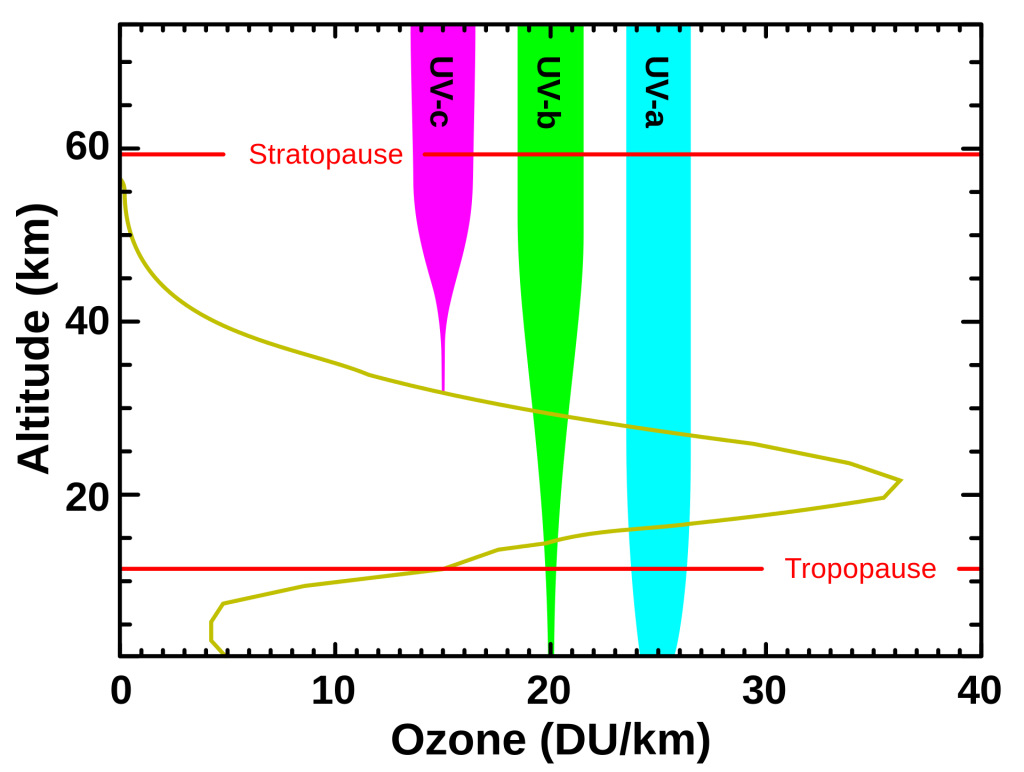

There are three types of UV light, each distinguished by their wavelengths: UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C. Stratospheric ozone molecules absorb all of the sun’s UV-C light and most of its UV-B light (Figure 5).

Reductions in stratospheric ozone levels led to higher levels of UV-B reaching the Earth’s surface, which is a serious hazard to human health. Studies have shown that in the Antarctic the amount of UV-B measured at the surface can double due to thinning of the ozone layer. UV-B is harmful to cells because it can interact with biomolecules like DNA and damage it. This can lead to mutations and cell death. UV-B cannot penetrate multicellular organisms very far and thus tends to only affect cells near the surface, such as in the skin of animals. Microbes like bacteria, however, are composed of only one cell and can therefore be killed by UV-B.

Laboratory and epidemiological studies demonstrate that UV-B causes certain types of skin cancers in humans and plays a major role in development of malignant melanoma (a particularly dangerous form of skin cancer). In addition, UV-B causes cataracts, a clouding of the lens in the eye that can lead to poor vision or even blindness.

It is important to note that all sunlight contains some UV-B light, even with normal stratospheric ozone levels. Therefore, it is important to protect your skin and eyes from the sun. Ozone layer depletion increases the amount of UV-B and the risk of health effects.

Short-Lived Climate Pollutants

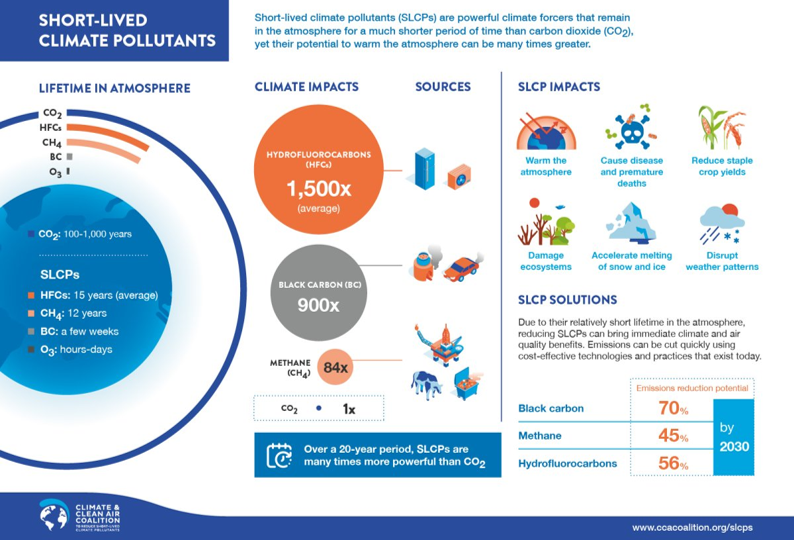

Ozone also acts as a short-lived climate pollutant, which causes an increase in the greenhouse effect similar to CO2, but which disperses quickly. Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) are air pollutants that increase radiative forcing, contributing to a warming global climate, but which leave the atmosphere on a short timescale ranging from hours up to 15 years (Figure 6). Essentially, positive radiative forcing means Earth receives more incoming energy from sunlight than it radiates to space because SLCPs and CO2 trap the heat energy reflected from the earth’s surface, causing atmospheric warming. Additionally, SLCPs impact human health, as do all air pollutants (Section 10.1). SLCPs may cause millions of premature deaths every year. Compared to SLCPs, excess CO2 remains in the atmosphere for 100 to 1,000 years.

Estimates for the relative responsibility of CO2 and SLCPs to anthropogenically-induced warming are that CO2 is responsible for about 60% and SLCPs are responsible for about 40% of the warming global climates The SLCPs are specifically black carbon, tropospheric ozone, methane, and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Fortunately, there are already some measures in place for regulating these atmospheric pollutants. The previously discussed Montreal Protocol can be applied to targeted reduction of hydrofluorocarbons (the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol).

Black Carbon: The main sources of black carbon are open burning of biomass, diesel engines, and the residential burning of solid fuels such as coal, wood, dung, and agricultural residues. Black carbon also harms human health; it is a primary component of fine particle air pollution (PM 2.5), which is a major health concern, and specifically can cause or contribute to asthma and other respiratory problems, low birth weights, heart attacks, and lung cancer. Though not all particulates released through combustion are dark or black color, with the lighter particles potentially leading to climatic cooling, there is evidence that the net effect is to increase climatic temperature. Any of these particulates released by combustion also increase the rate of melting of ice and snow, because deposition of particles, including dust, reduces the reflectivity (albedo) of snow and ice, allowing more solar radiation to be absorbed, causing faster melting.

Tropospheric ozone: Lower atmosphere (tropospheric) ozone is a major air and climate pollutant which causes warming and is harmful to human health and crop production. Breathing ozone is particularly dangerous to children, older adults and people with lung diseases, and can cause bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, and may permanently scar lung tissue. Its impacts on plant include not only lower crop yields but also a reduced ability to absorb CO2.

Tropospheric ozone is not emitted directly but instead forms from reactions between precursor gases, both human-produced and natural. These precursor gases include carbon monoxide, oxides

of nitrogen (NOx), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which include methane. Globally increased methane emissions are responsible for approximately two thirds of the rise in tropospheric

ozone. Reducing emissions of methane will lead to significant reductions in tropospheric ozone and its damaging effects.

Methane: Methane (CH4) is released naturally from wetlands, but about 60% of current methane emissions are attributed to anthropogenic activity. An additional worry is that climate change could increase atmospheric methane levels by increasing methane production in natural ecosystems, forming a positive feedback. The main sources of anthropogenic methane emissions are oil and gas systems; agriculture, including enteric fermentation, manure management, and rice cultivations; landfills; wastewater treatment; and emissions from coal mines. Methane is the primary component of natural gas, with some emitted to the atmosphere during its production, processing, storage, transmission, and distribution.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HCFs): HFCs are factory-made chemicals used primarily in refrigeration

and insulating foams. They have a warming effect hundreds to thousands of times more powerful than CO2. The average lifetime of the mix of HFCs, weighted by usage, is 15 years. HFCs are the fastest growing greenhouse gases in many countries, including the U.S., where emissions grew nearly 9% between 2009 and 2010 compared to 3.6% for CO2. Globally, HFC emissions are growing 10 to 15% per year and are expected to double by 2020. Fast action is needed to limit their growth.

Attribution

Environmental Science by Matthew R. Fisher is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from the original by Joni Baumgarten.

Methane by Wikipedia is licensed CCA-SA 3.0. Modified by Joni Baumgarten. Accessed 03-09-2023.

Primer on SLCP by Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development. 2013. Used as a reference for “Short Lived Climate Pollutants”, by Joni Baumgarten, licensed CC BY 4.0.

Radiative Forcing by Wikipedia is licensed CCA-SA 3.0. Modified by Joni Baumgarten. Accessed 03-09-2023.