3.2 The Scientific Method and Sociological Research

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off-limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries and in education that have helped structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a question about a new trend or a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

Developing a Research Question

As sociology made its way into American universities, scholars developed it into a science that relies on research to build a body of knowledge. Sociologists began collecting data (observations and documentation) and applying the scientific method or an interpretative framework to increase understanding of societies and social interactions.

Our observations about social situations often incorporate biases based on our views and limited data. To avoid subjectivity, sociologists conduct systematic research to collect and analyze empirical evidence. Peers review the conclusions from this research. Examples of peer-reviewed research are found in scholarly journals.

Sociologists use a variety of methods for research, such as surveys, ethnographies (field research), and interviews. Humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. However, scientific models and the scientific process of research can be applied to the study of human behavior. A scientific approach to research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The Steps of the Scientific Method

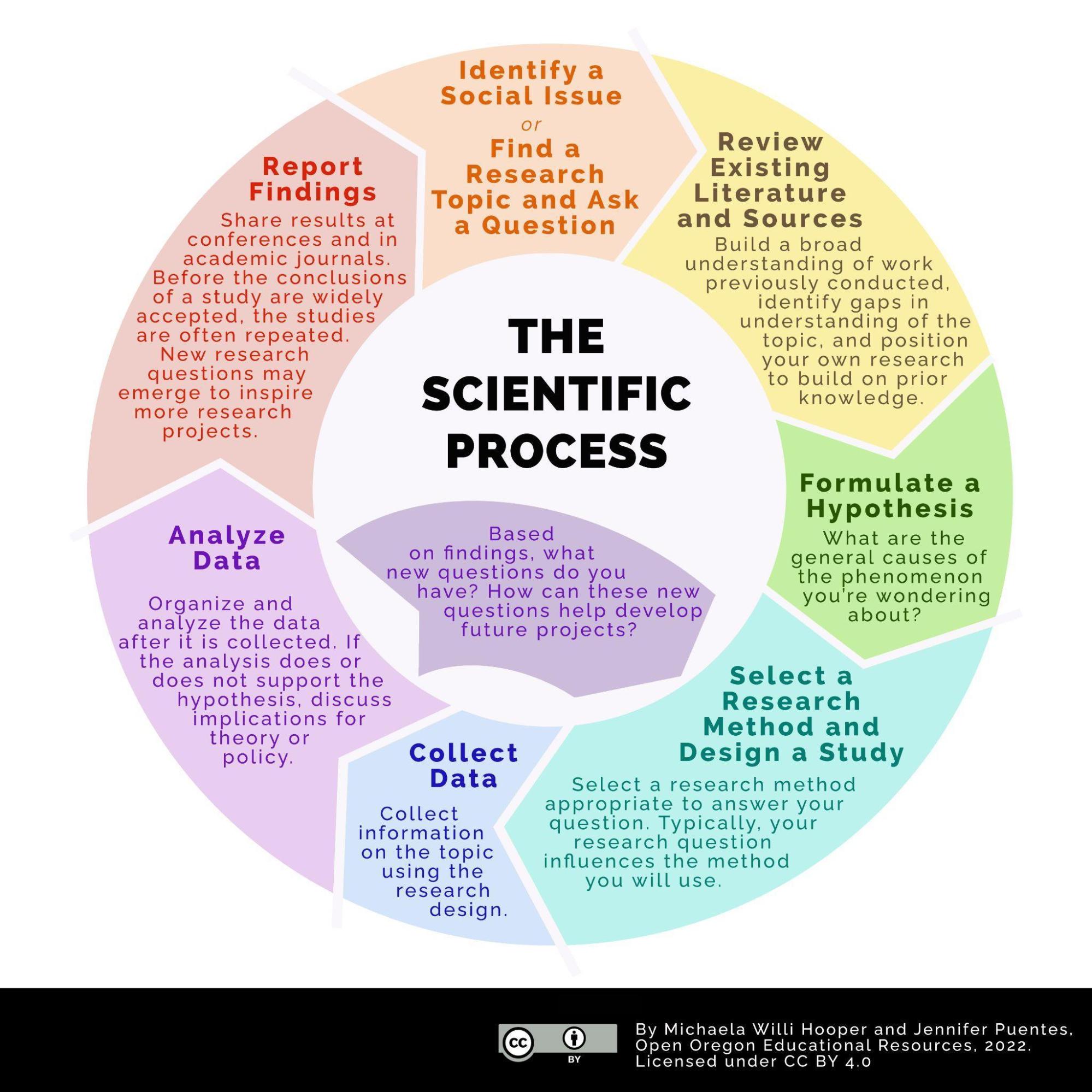

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. The scientific method follows deductive reasoning, rather than the inductive approach we see with grounded theory. It involves a series of seven steps as shown in figure 3.2. Not every research project follows the steps in order, but this approach provides a plan for conducting research systematically.

Figure 3.2 outlines key stages in the research process. Please note that these stages or steps can be experienced as an ongoing process. Researchers and students undertaking projects may need to repeat steps as they go through the research process.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of community cohesiveness, employment, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, neighborhood organizations, and higher education patterns.

Good research questions address sociological issues, connect to prior sociological research studies, are narrow enough that one study could help answer it, and can be examined through data (readily available or able to be collected, given your time and resources) (Smith-Lovin and Moskovitz 2017:57). The process of designing research questions emphasizes first reviewing the previous literature to identify connections the researcher should explore in their study (Loske 2017). This is something you will want to keep in mind; it is not uncommon for research questions to evolve as you continue to incorporate new literature.

Step 1: Identify a Social Issue/Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” is too vague. The question should also be broad enough to be of significance. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” is too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then” statement. Let’s relate this to the topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variable, which is the cause of the change, and a dependent variable, which is the effect, or the thing that is changed. In the previous example, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

With a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by the level of education (the independent variable)? The table in figure 3.3 demonstrates the relationship between a hypothesis, independent variable, and dependent variable.

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the houseless rate. | Affordable Housing | Houseless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighborhood. | Police Patrol Presence | Safer Neighborhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of media coverage, the higher the public awareness. | Observation | Public Awareness |

Taking an example from figure 3.3, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, that this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two related topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Select a Research Method and Design a Study

In this step, researchers select a research method that is appropriate for answering their research question. Surveys, experiments, interviews, ethnography, and content analysis are just a few examples that researchers may use. You will learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter in the section Research Methods. Typically, your research question influences the type of methods that will be used.

Step 5: Collect Data

Next the researcher collects data. Depending on the research design (step 4), the researcher will begin the process of collecting information on their research topic. After all the data is gathered, the researcher will be able to organize and analyze the data.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

After collecting the data, sociologists categorize and analyze it to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss what this might mean. For example, there could be implications for public policy or existing theories. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, that can be an important finding to report.

Even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, the results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. For example, in a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many people assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Step 7: Report Findings

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. Sociological theories and knowledge develop as the relationships between social phenomena are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

Licenses and Attributions for the Scientific Method and Sociological Research

Open Content, Original

“The Scientific Method and Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The Scientific Method and Sociological Research” from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include editing for clarity and brevity.

First two paragraphs of “Developing a Research Question & the Steps of the Scientific Method” from “Introduction” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Paragraphs three and four from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include editing for consistency and brevity, including figure 3.3 and Step sections.

“The Scientific Method and Sociological Research” is modified from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include editing paragraphs 3, 4, and Steps 1–7 for consistency and brevity.

Figure 3.2. “Stages of the Scientific Method and Research Process” is adapted from The Scientific Method as an Ongoing Process by Whatiguana, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications: Updated text and design by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources.

a lens that allows you to view society and social structures through multiple perspectives simultaneously.

a sociological research approach that seeks in-depth understanding of a topic or subject through observation or interaction; this approach is not based on hypothesis testing. Interpretive frameworks allow researchers to have reflexivity so they can describe how their own social position influences what they research.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

one-on-one conversations with participants designed to gather information about a particular topic.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

the net value of money and assets a person has. It is accumulated over time.

a behavior that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

a method of collecting data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods.

an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

the study of people in their environments to understand the meanings they give to their activities.

a systematic approach to record and value information gleaned from secondary data as it relates to the study at hand.