11.5 Race and Identities

How do we develop racial and/or ethnic identities? There are several different approaches to understanding the process of identity development. A few key principles center on one’s ability to either self-identify with a group or be labeled as a member of a group by others.

Our racial and ethnic identities may provide us with a sense of belonging as we develop positive attitudes toward one’s group. Think back to the video you watched at the beginning of the chapter. What stories did the speakers share that helped you understand belonging to and developing positive attitudes toward group membership? Our identities also grow through social participation in cultural practices. For many groups, racial and ethnic identities offer an opportunity to practice shared languages, develop friendships, and engage in religious practices.

Racial Identity Development

As you learned in Chapter 4, there are many different theories on the process of self and identity development, including W. E. B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness. In this section, we will focus primarily on theories that focus on racial identity and ethnic identity development.

Non-White Racial Identities

In her influential book, Why Are all the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations about Race, Beverly Tatum examines identity formation for Black and White youths. She applies a theory of identity development first created by social psychologist William Cross. Cross (1971, 1991, 2001) suggests there are five stages in the development of a Black identity:

- Pre-encounter: Children absorb beliefs and values of dominant White culture, including the idea that it’s more favorable to be White. Unless parents and teachers encourage critical evaluation of these messages, children will not critique them.

- Encounter: In early adolescence, an event or series of events forces a young person to acknowledge the personal impact of racism. The individual begins to grapple with what it means to be a member of a group targeted by racism.

- Immersion/Emersion: During this stage, people begin to surround themselves with symbols of their racial identity. They may seek out opportunities to learn about one’s history and culture while actively avoiding symbols of Whiteness.

- Internalization: People begin to gain a sense of security about their racial identity and develop meaningful relations across group boundaries. People will continue to surround themselves with symbols of their racial identity and associate with their racial group.

- Internalization-Commitment: A stronger sense of security about one’s racial identity develops. This sense of security translates into activism about the concerns of one’s racial group.

Tatum (2017 [1997]) finds evidence to support Cross’ theory of racial identity formation. In her study, youth of color internalized the negative stereotypes that are dominant in White culture. Many youths of color tried to assimilate to receive acceptance from Whites and distanced themselves from other people of color. As they entered into the encounter stage, they began to recognize the impact of racism on their lives. After learning more about their racial identity group and unlearning internalized stereotypes, youth may exhibit resentment for racism and develop an oppositional identity (Tatum 2017 [1997]). By defining themselves in opposition to Whites, they develop their own music, dress, speech patterns, and a supportive community for one another.

Youth of color may be ostracized by other youth of color for socializing with White youth or living in the suburbs. During the internalization stage, Tatum saw youths develop the ability to maintain connections with their peers while also building relationships with Whites who are respectful of their definition of racial identity. At this point, individuals began developing coalitions with other oppressed groups. In the commitment stage, youths’ sense of Blackness emerged into a plan of action focused on the concerns of Blacks as a group. Stages in this model are not linear; after completing a stage, individuals may return to that stage later. However, their experience may change. The main ideas presented in Cross’ work and elaborated on by Tatum have been adopted by others to theorize the development of other cultural identities, including minority, racial, ethnic, feminist, and gay/lesbian identities.

Another approach to understanding ethnic identity development centers on Jean Phinney’s work, which uses a three-stage model: unexamined, identity search, and achieved ethnic identity. Initially, race and ethnicity are not particularly salient for the individual. During this stage, children are not exposed to ethnic identity issues and often express a preference for the dominant culture. As individuals begin the identity search stage, they actively look for ways to define themselves as members of their own racial or ethnic group. Something typically occurs that forces an “awakening” or awareness of one’s ethnicity. In the final stage, individuals can assert a positive sense of their ethnic identity. At this point, they may have come to terms with cultural differences between their group and the dominant group (Phinney 1996).

White Racial Identities: An Unspoken Norm of Whiteness

We tend not to think about the experiences of White people when we talk about race because we live in a society where the experiences of White people are already at the forefront of our minds. For a lot of White people, Whiteness is an unexamined norm. A White person can reach adulthood without having to think about their racial group and the privileges it may provide. Instead, race is seen as something other people have. This leads to a lack of critical understanding and appreciation of the experiences of Whiteness and the diversity within the group, particularly as you look at how Whiteness intersects with other identities.

To abandon practices of individual racism and move toward recognizing and opposing institutional racism, White folks need to experience several stages of identity development. Tatum (2017 [1997]) draws on the work of Janet Helms to discuss the six stages of White identity formation:

- Contact (Pre-Contact): The White person is not aware of themself as a racial being. They may view people of color through stereotypes learned from family, friends, and media. They see racism as a form of individual prejudice, rather than systemic in nature.

- Disintegration (Encounter): The White person begins to see racism as a problem and can identify that their lives and the lives of people of color are impacted by racism. Whites may experience guilt, shame, and anger as they recognize their position as part of an oppressive system. They may withdraw, experience denial, and place blame on victims. Or they may speak out, risking rejection from other White people.

- Reintegration: The White person experiences social pressure to be accepted by their racial group. Pressure to not speak out against racism is prevalent and may reshape an individual’s belief system.

- Pseudo Independence: The White person can move beyond victim blaming and deepen their awareness of racism, but they seek answers from people of color. They may express a commitment to understanding racism as a system of disadvantage, but they do not know how to create change.

- Immersion/Emersion: The White person seeks to replace previously held racial stereotypes and myths about race with accurate information. Rather than look to people of color to help find solutions to deal with issues of Whiteness, they look to other Whites to help them deal with racism.

- Autonomy: The White person begins to confront oppressions in daily life by implementing the issues they began working on in the immersion/emersion phase. They actively seek to develop a positive and constructive racial identity.

Disintegration is an important turning point in White identity development. Tatum suggests that to change an oppressive system, Whites need to learn to feel comfortable with the discomfort they experience when calling out racism. Social pressure placed on Whites by other Whites may lead to collusion, during which a person will begin to accept racism and even start to blame the victim. During this stage, Whites may experience fear and anger toward people of color as a reaction to the discomfort they feel.

If Whites make it through disintegration but avoid interacting with people of color, it is easy for them to become stalled in the reintegration stage of development (Helms 1990). During the stage of immersion, Whites are on their way to becoming an ally. They seek out ways to unlearn racism and find ways to participate in the fight for racial justice. Finally, in the last stage, people incorporate a White antiracist identity and join with people of color to dismantle White power and privilege within institutions.

Developing an Antiracist White Identity

Almost all mainstream voices in the United States oppose racism. Despite this, racism is prevalent in several forms. For example, when a newspaper uses people’s race to identify individuals accused of a crime, it may enhance stereotypes of a certain minority. Another example of racist practices is racial steering, in which real estate agents direct prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race.

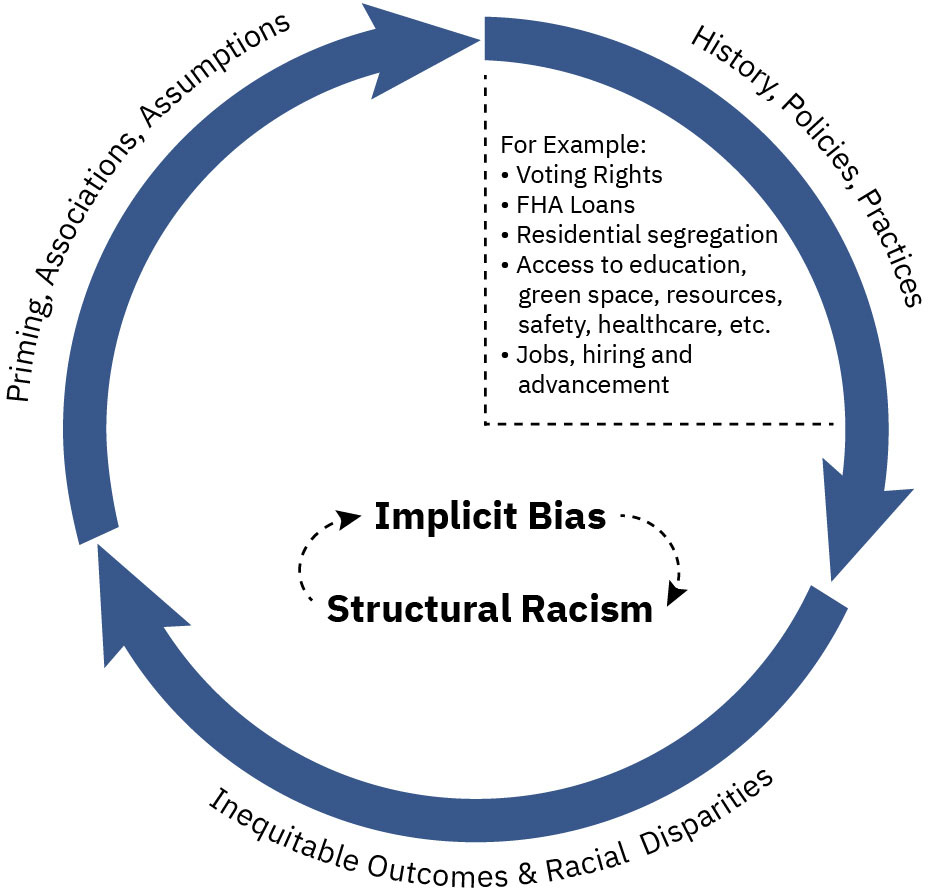

Racist attitudes and beliefs are often more insidious and harder to pin down than specific racist practices. They become more complex due to implicit bias (also referred to as unconscious bias) which is the process of associating stereotypes or attitudes with categories of people without conscious awareness—which can result in unfair actions and decisions that are at odds with one’s conscious beliefs about fairness and equality (figure 11.11) (Osta and Vasquez 2021). For example, the practice of “tracking” which involves sorting students based on actual or assumed differences in academic development or interests can have long-term effects on students’ opportunities. In schools, we often see “honors” and “gifted” classes quickly filled with White students while the majority of Black and Latinx students are placed in the lower track classes. As a result, our mind consciously and unconsciously starts to associate Black and Latinx students with being less intelligent and less capable. Osta and Vasquez (2021) argue that by placing the students of color on a lower and less rigorous track, we reproduce the inequity, and the vicious cycle of structural racism and implicit bias continues.

Proponents of antiracism indicate that we must work collaboratively within ourselves, our institutions, and our networks to challenge racism at local, national, and global levels. The practice of antiracism can include the following:

- Understand and own the racist ideas in which we have been socialized and the racist biases that these ideas have created within each of us.

- Identify racist policies, practices, and procedures and replace them with antiracist policies, practices, and procedures (Carter and Snyder 2020).

Antiracism need not be confrontational in the sense of engaging in direct arguments with people, feeling terrible about your privilege, or denying your own needs or success. Many people who are a part of a minority group acknowledge the need for allies from the dominant group (Melaku 2020). Understanding and owning the racist ideas, and recognizing your privilege, is a good and brave thing. As proponents of this approach suggest, being racist or antiracist is not about who you are; it is about what you do (Carter and Snyder 2020).

Licenses and Attributions for Race and Identities

Open Content, Original

“Race and Identities” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Developing an Antiracist White Identity” and figure 11.11 from “11.3 Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency, clarity, and brevity.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

concept developed by W.E.B. Du Bois referring to a sense of “twoness” experienced by African-Americans because of their racialized oppression and devaluation in a white-dominated society

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

a type of prejudice and discrimination used to justify inequalities against individuals by maintaining that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is a set of practices used by a racial dominant group to maximize advantages for itself by disadvantaging racial minority groups.

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

the values, norms, meanings, and practices of the group within society that is the most powerful.

a group that holds the most power in a given society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

the presence of differences, including psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among individuals.

also called structural racism or systemic racism; involves systems and structures that have procedures or processes that disadvantage racial minority groups.

the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

a behavior that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions.

also referred to as unconscious bias; the process of associating stereotypes or attitudes towards categories of people without conscious awareness.

an active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies, and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.

any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.