2.4 Applying the Discipline: American Theorists and Practitioners

In the early 1900s, sociology reached universities in the United States. William Sumner held the first professorship in sociology (Yale University), Franklin Giddings was the first full professor of Sociology (Columbia University), and Albion Small wrote the first sociology textbook. Early American sociologists tested and applied the theories of the Europeans and became leaders in social research. Lester Ward (1841–1913) developed social research methods and argued for the use of the scientific method and quantitative data to show the effectiveness of policies. For sociology to gain respectability in American academia, social researchers understood that they must adopt empirical approaches.

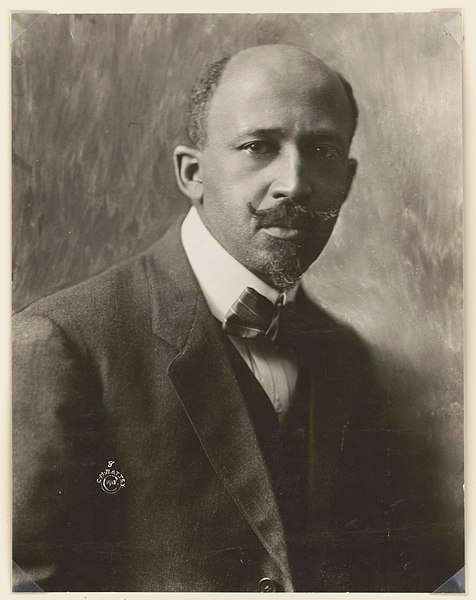

Race in America: W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963)

William Edward Burghardt (W. E. B.) Du Bois, a Harvard-trained historian, pioneered the use of rigorous empirical methodology in sociology (figure 2.12). His groundbreaking 1896–1897 study of the African-American community in Philadelphia incorporated hundreds of interviews Du Bois conducted to document familial and employment structures and assess the chief challenges of the community. Published as The Philadelphia Negro (1899), it was the first American urban ethnography. These new, comprehensive research methods stood in stark contrast to the less scientific practices of the time, which Du Bois critiqued as being similar to researching through the window of a moving car. His scientific approach became highly influential to entire schools of sociological study and is considered a forerunner to contemporary practices.

In addition, he was the first sociologist of race. Race was at the center of his theorizing and work. He argued that race is a social construct and could not be reduced to biology or a scientific category. This challenged pseudoscientific ideas of biological racism (Morris 2017; Green and Wortham 2018), which had been used as justification to oppress people of different races. His book analyzing the Reconstruction after the American Civil War still provides insights into contemporary American society (Bouie 2022).

Du Bois also played a prominent role in the effort to increase rights for Black people. Concerned by the slow pace of progress and some Black leaders’ recommendation that Black people be more accommodating of racism, Du Bois became a leader in what would later be known as the Niagara Movement. In 1905, he and others drafted a declaration that called for immediate political, economic, and social equality for African Americans. A few years later, he helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as its director of publications.

Even with his important sociological insights and activism, Du Bois has been largely ignored and erased by sociologists. Only recently has there been an interest in creating a Du Boisian sociology (Morris 2022).

A Closer Look: Du Bois and Double Consciousness

Watch the following video based on Du Bois’s writing about the experiences of being Black in the United States (figure 2.13). We will revisit this idea in a later chapter.

Meaning-Making and Interaction in the City: The Chicago School of Sociology

In 1892, the department of sociology was founded at the University of Chicago. For the next 40 or so years, the department was the center of American sociology. Several influential textbooks emerged from the school, the American Journal of Sociology was founded, and members of the school played important roles in establishing the professional association for sociologists called the American Sociological Society (ASS, now known as the American Sociological Association, or ASA). For more information, you have the option to explore the ASA website.

During that time, Chicago was undergoing a rapid transformation. The city was industrializing, with major growth in the manufacturing and retail sectors. There were large numbers of people immigrating to the area, including people from nearby rural areas, African Americans from the southern United States, and immigrants from Eastern Europe. This led to a rather ethnically and racially diverse city.

Sociologists at the University of Chicago sought to explain these changes while also focusing on marginal groups. They did this by going out into the field and collecting data on the everyday lives of people in Chicago. Their research included studying immigrants (Thomas and Znaniecki 1996), gangs (Thrasher 2013 [1927]), homeless bohemians (hobos) (Anderson 2014 [1961]), and taxi-hall dancers (Cressey 2008 [1932]). Theories of the self developed by Charles Cooley (1864–1929) and George Herbert Mead (1863–1931), which we will explore in Chapter 4, also informed their perspective.

Jane Addams (1860–1935) worked closely with the University of Chicago’s Chicago School of Sociology. She founded Hull House, a center that served needy immigrants through social and educational programs while providing extensive opportunities for sociological research. Research conducted at Hull House informed child labor, immigration, health care, and other areas of public policy.

Some other well-known Chicago School sociologists include Robert Park (1864–1944), W. I. Thomas (1863–1947), Ernest Burgess (1886–1966), and Everett Hughes (1897–1983). By the 1940s and 1950s, the influence of the Chicago School within American sociology had begun to decline.

Licenses and Attributions for Applying the Discipline: American Theorists and Practitioners

Open Content, Original

“Applying the Discipline: American Theorists and Practitioners” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Introductory paragraph in “Applying the Discipline” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Race in America” is modified from “1.2 The History of Sociology”by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Added detail on the Philadelphia Negro, social construction of race, and continued relevance of Du Bois. Edited for consistency.

Paragraph on Jane Addams in “Meaning-Making and Interaction in the City” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.12. “W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois, 1868–1963” the Public Domain. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.13. “How Does it Feel to Be a Problem?” by The Atlantic is shared under the Standard YouTube License.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

one-on-one conversations with participants designed to gather information about a particular topic.

the study of people in their environments to understand the meanings they give to their activities.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a type of prejudice and discrimination used to justify inequalities against individuals by maintaining that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is a set of practices used by a racial dominant group to maximize advantages for itself by disadvantaging racial minority groups.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.