2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

During the mid-twentieth century in the United States, three dominant theoretical frameworks emerged: structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. You are likely to encounter these theories in your introductory sociology courses. As you will see, these frameworks draw on different combinations of the work of the classical theorists while attempting to explain social phenomena. Similar to the classical theorists, mid- to late-twentieth-century American sociologists seldom questioned whose voices they included and whose voices they excluded.

Structural Functionalism

Structural functionalism was the dominant theoretical framework in American sociology from the 1940s into the 1960s and 1970s. Functionalist theorists drew from Durkheim’s work and from a rather narrow interpretation of Weber’s. Structural functionalism tends to focus on macro-level phenomena, such as the relationship between institutions.

Functionalists proposed that society is a stable system made up of interrelated parts. Those parts constitute the different institutions within the society, such as the education system, families, and the economy. Each of those parts has a function that contributes to the stability of the whole system. They solve a particular problem for society. For example, families and schools help socialize and educate young people, and the economy helps solve the problem of distributing and producing goods.

Within this framework, social integration is important because that is how people come to feel connected within their society. As an example of social integration, think back to Durkheim’s discussion of the different types of solidarity. In modern societies, common rituals and shared values help people feel connected. Based on this framework, it may seem that societies are relatively stable and lack conflict. However, conflict can emerge when different institutions tell us to do different things. This can result in social strain and deviance, which we will explore in more depth in Chapter 7.

A figurehead of functionalism, Talcott Parsons (1902–1979) was concerned with the problem of order. He tended to think through problems and issues in an abstract and at times an unclear way. Robert Merton (1910–2003), a student of Parsons and the functionalist tradition, broadened the concerns of functionalism by developing a unique blend of his teacher’s abstraction and data. He argued for theories that integrated abstract theorizing and empirical research. He saw exemplars of this in Durkheim’s theory of suicide and Weber’s arguments about the Protestant work ethic (figure 2.14) (Ritzer and Stepnisky 2022).

Structural functionalism has been heavily criticized within sociology. Some critics argue that functionalists present a rather static view of society that fails to account for social change. Others argue there are logical flaws within the framework. Specifically, critics argue there is a problem in assuming that everything that persists in society serves a function. For example, does poverty or discrimination provide a function for society? Functionalism also has a hard time explaining inequality and, at its worst, may help justify existing inequalities.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory is another macro-level theory. It arose in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s against the backdrop of the rise of various social movements. It draws heavily from Marx, and to some extent from Weber, and in doing so challenges functionalism.

In this framework, conflict is a basic fact of social life. Groups with antagonistic interests are constantly struggling with each other. In the classical Marxist formulation, it is the owners versus the workers. Beyond class, it could include men versus women, White people versus people of color, and so on.

Rather than seeing institutions as benign, conflict theorists argue the institutions of society promote the interests of the powerful while subverting the interests of the powerless. For example, consider how school funding is distributed. Schools in urban areas receive less financial support compared to their suburban counterparts. Those in suburban schools are given tools to get ahead, while those in urban schools are not (Kozol 1991). As a result, the students who go to well-funded schools have pathways into college and well-paying jobs. For the students that attend schools with fewer resources, they face barriers that can make it hard to get ahead.

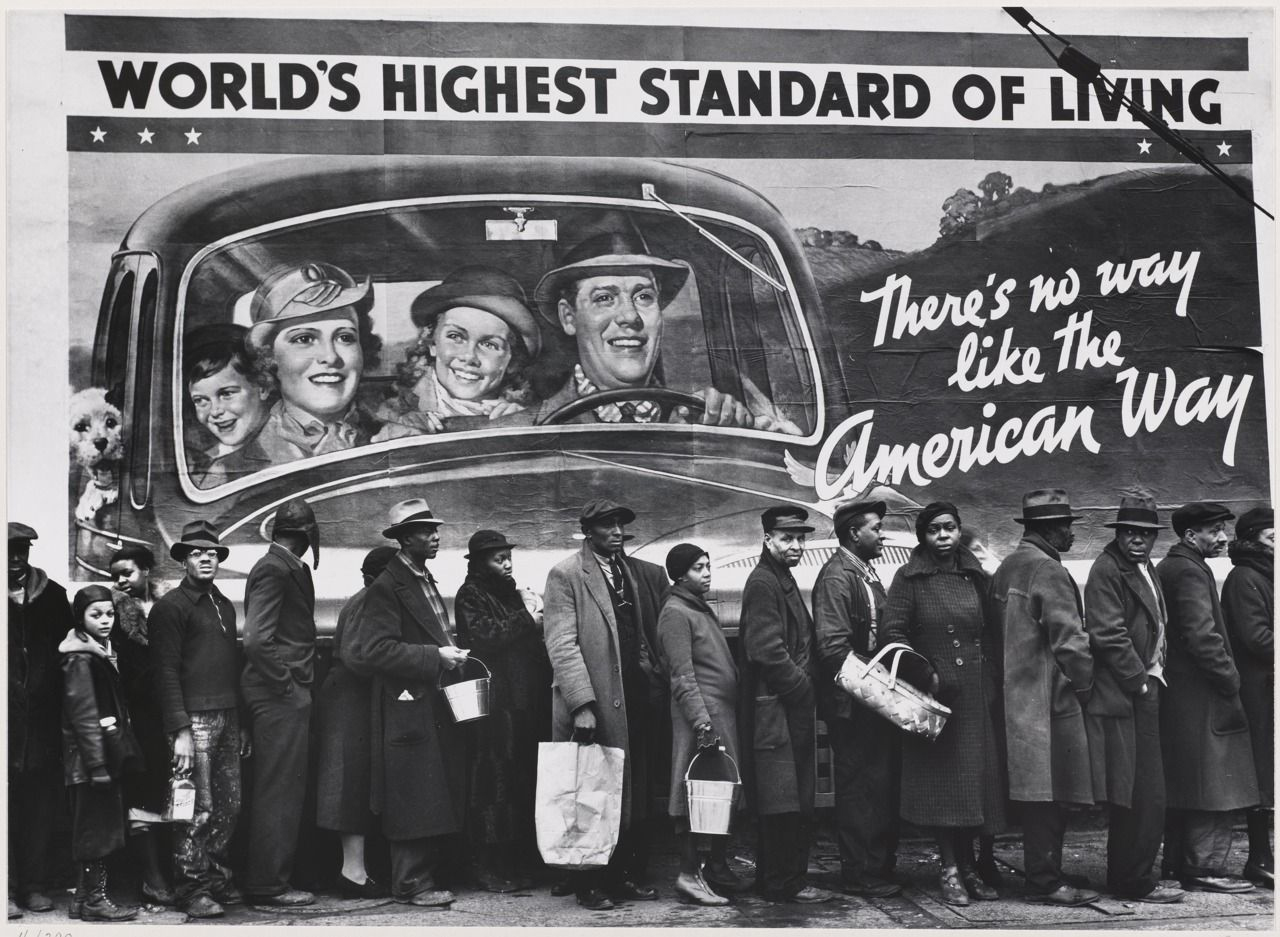

Instead of viewing common rituals and shared values as integrating people into society, conflict theorists argue these values and rituals are ideologies that deceive people and make them comfortable with their position in society. One dominant ideology within the United States that is heavily criticized by conflict theorists is the idea of the “American Dream,” which proposes that if you work hard, you will get ahead. Conflict theorists argue that the opportunities to get ahead for most people are severely curtailed due to artificial barriers in most institutions (figure 2.15). The American Dream ideology, according to conflict theorists, justifies the position of those already at the top of the power structure (Colomy 2010).

For conflict theorists, social change emerges from people organizing and mobilizing together to pressure the institutions of society. Change is not something that will emerge from within the institutions. Recent social movements related to environmental justice are a good example of this.

Some well-known conflict theorists include C. Wright Mills (1916–1962), Ralf Dahrendorf (1929–2009), and Randall Collins (1941–).

Critics of conflict theory argue that it overemphasizes social change. It is also seen as centering social class in the analysis of the social world, rather than other sources of oppression and privilege, such as race and gender. We will revisit this perspective in Chapter 8.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism grew out of the Chicago School of Sociology. Unlike functionalism and conflict theory, symbolic interactionism provides a micro-level theory for understanding society.

The most famous statement on symbolic interactionism was made by Herbert Blumer, who coined the term “symbolic interactionism” in 1937. Blumer was a student of several sociologists at the Chicago School.

Blumer (1986 [1969]:2) stated that symbolic interactionism was based on the following premises:

- “Humans act toward things on the basis of the meanings they ascribe to those things.”

- “The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with others and the society.”

- “These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he/she encounters.”

In other words, interactionists are concerned with how meanings are constructed through interactions with others. We attach meanings to situations, roles, relationships, and things whenever we encounter them. For a symbolic interaction to occur, these meanings have to be shared and agreed upon by the people you are interacting with.

For example, if we attach the meaning of “family member” to someone, we will treat them as a family member (or act based on the meaning of family member) as we interact with them. What we define as family originates from interactions with others, such as parents, siblings, teachers, the media, and elsewhere. As we interact with other people, we may come to modify our interpretations of what it means to be family, especially if the people we are interacting with have more inclusive or exclusive definitions of family.

Erving Goffman (1922–1982), Howard Becker (1928–), Sheldon Stryker (1924–2016), Patricia (1952–) and Peter Adler (1952–), and Gary Alan Fine (1950–) are some well-known interactionists.

Critics argue that symbolic interactionism has a hard time explaining macro-level phenomena. Other critics argue that it tends to downplay power, privilege, and oppression. Some present-day interactionists have tried to correct these problems by showing how symbolic interactionism can be used to explain power (Athens 2010) and organizational patterns (Hallett and Ventresca 2006). Within sociology, a separate professional association, the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction (SSSI), continues to debate symbolic interactionism. We will explore this framework more in Chapter 4.

For a comparison of the three theories, check out figure 2.16.

| Sociological Theories/Paradigms | Level of Analysis | Focus | Analogies | Questions That Might Be Asked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Functionalism | Macro or Mid | The way each part of society functions together to contribute to the functioning of the whole. | How each organ works to keep your body healthy (or not). | How does education work to transmit culture? |

| Conflict Theory | Macro | The way inequities and inequalities contribute to social, political, and power differences and how they perpetuate power. | The ones with the most toys win, and they will change the rules to the games to keep winning. | Does education transmit only the values of the most dominant groups? |

| Symbolic Interactionism | Micro | The way one-on-one interactions and communications behave. | What does it mean to be an X? | How do students react to cultural messages in school? |

Licenses and Attributions for Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

Open Content, Original

“Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Matthew Gougherty is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 2.14. “Grey Leather Office Rolling Armchair Beside White Wooden Computer Desk” by James McDonald is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 2.15. “American way of life” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.16. “Sociological Theories or Perspectives” from “1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

a macro-level theory that proposes society is made up of stable institutions and each institution has a function for the society.

a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns.

a micro-level theory that emphasizes the importance of meanings and interactions in social life.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

a violation of contextual, cultural, or social norms.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

a macro level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life. It tends to argue that the institutions of society benefit the powerful.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

in Marxist theory, the dominant ideas of a time period. It reflects the interests of the owners and makes what is socially constructed seem natural.

a combination of prejudice and institutional power that creates a system that regularly and severely discriminates against some groups and benefits other groups.

something of value members of one group have that members of another group do not, simply because they belong to a group. The privilege may be either an unearned advantage or an unearned entitlement.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.