7.4 Modern Theories of Deviance

Jennifer Puentes; Matthew Gougherty; and Alexandra Olsen

In response to the historical theories of deviance, new theories emerged that critiqued or expanded upon them to address shortfalls in their explanations. At the end of this section, figure 7.6 summarizes these key theories.

Robert Merton’s Functionalist Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory, which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. Merton defined five ways people respond to the gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it. To understand the five ways people respond, we’ll look at the somewhat exaggerated example of the American Dream: the idea that to be successful, you should own a house, a car, and have a happy and functional family.

- Conformity: People who conform choose not to deviate. They pursue their goals to the extent that they can through socially accepted means.

Example: “I may not be able to afford to buy a house in my lifetime, but I have a working car, a loving partner, and a cute dog. I’m content with the lot I’ve been given in life.” - Innovation: People who innovate pursue goals they cannot reach through legitimate means by instead using criminal or deviant means.

Example: “I grew up in a neighborhood that didn’t have good schools, and I never had an opportunity to get ahead. I want a house, a nice car, and to take care of my family, but the only way I can see myself doing that is by continuing to sell cocaine and counterfeit goods.” - Ritualism: People who ritualize lower their goals until they can reach them through socially acceptable ways. These members of society focus on conformity rather than attaining a distant dream.

Example: “I’m never going to be able to afford a nice home and car, but I don’t need those things anyway! I like the apartment I rent, and my cat’s the only other form of life I want to be responsible for. Why not just love the things that I do have?” - Retreatism: People who retreat reject society’s goals and means.

Example: “Why would I even participate in society at all? The deck is stacked against me. I know I’m only 20, but (illegally) hopping on trains and traveling around the country with my friends is where it’s at! ” - Rebellion: People who rebel and replace a society’s goals and means with their own. Terrorists or freedom fighters look to overthrow a society’s goals through socially unacceptable means.

Example: “I’m gonna overthrow the government, that’s what I’m going to do! The system is unjust, and it’s not one that’s designed for how humans really are!”

William Julius Wilson and Conflict Theory: Rethinking the Role of Neighborhoods

William Julius Wilson refined ideas in social disorganization theory to explain why people in poverty, particularly members of Black and immigrant communities, are more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods. Rather than focusing on the role of cultural factors like previous theorists, Wilson (1987) focused on how economic changes have contributed to these groups being more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods.

Wilson (1997) argued that, before the decline of industrial and manufacturing jobs, these groups could be economically successful despite having low levels of education due to their access to high-paying factory jobs. When these jobs disappeared, Black people and recent immigrants became trapped in low-income, high-crime areas with few jobs or low-wage, service sector jobs. According to Wilson’s (1997) theory, crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high-crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement. While providing important insights, Wilson’s theorizing has sometimes been criticized for focusing too much on social class.

Michele Foucault: Discipline and Punishment Theory

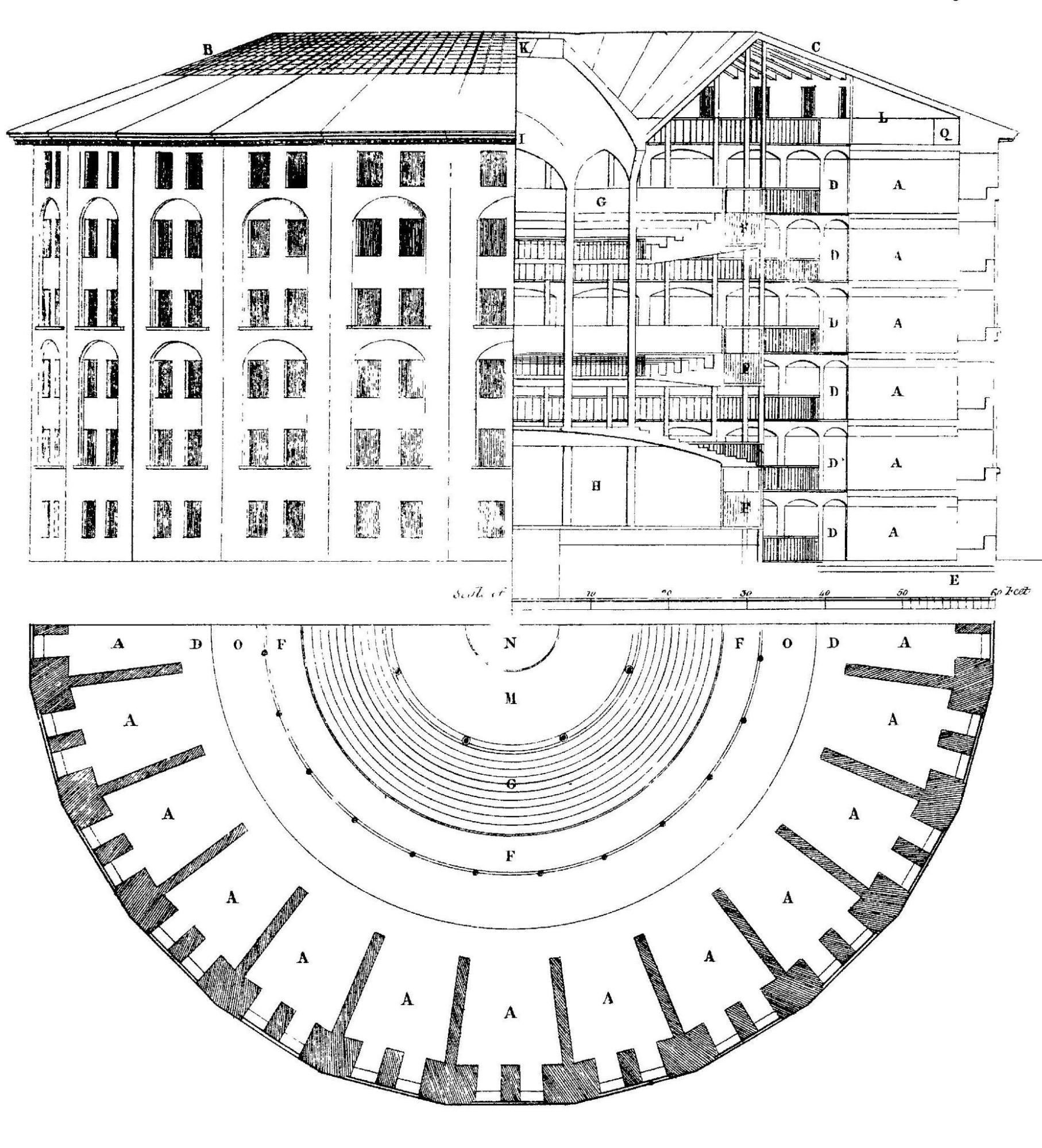

The panopticon, as seen in figure 7.5, is a late eighteenth-century circular prison designed by philosopher Jeremy Bentham. In the panopticon prison design, guards could continuously monitor prisoners without the prisoners knowing if the guards were watching. Since prisoners would not know when guards were watching them, they would constantly surveil their behavior to avoid punishment. French philosopher Michele Foucault (1977) drew parallels between Jeremy Benthan’s panopticon and how modern institutions control the population. He argued that punishment currently occurs through discipline and surveillance by institutions, such as prisons, mental hospitals, schools, and workplaces. These institutions produce compliant citizens without the threat of violence.

Ultimately, Foucault (1977) argued that surveillance created an effect where individuals conformed to society because they never knew if they were being watched. His ideas have gained new importance with the rise of surveillance technologies, which make it harder to engage in deviance without getting caught. Examples of this phenomenon are federal mass surveillance policies and the rise of police departments using technologies to scour social media networks for information about criminal activities. Broadly, Foucault (1977) proposed that social control and punishment are not just formal sanctions, like a prison sentence or ticket, but also something more mundane and built into social institutions.

Lemert’s Symbolic Interactionist Labeling Theory

Rooted in symbolic interactionism, labeling theory examines how members of society ascribe a deviant behavior to another person. What is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that do not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. In secondary deviance, a person who has been labeled a deviant may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that applied the label. In many ways, secondary deviance is captured by the assertion, “If you tell a child that they’re a bad kid often enough, they’ll eventually believe that they’re a bad kid.” This perspective hits on how negative social labels, especially of juveniles, have the power to create more deviant or criminal behavior.

Often, the labels imposed by those with power lead to the unequal treatment of disadvantaged groups. This can be particularly problematic in school settings. For example, Morris (2005) found that adults in an urban school labeled African-American girls as not “ladylike.” As a result, the adults tried to discipline the girls’ clothing and behaviors, in ways they thought were gender appropriate.

Sykes and Matza’s Techniques of Neutralization

How do people deal with the labels they are given? This was the subject of a study done by Gresham Sykes and David Matza (1957). They studied teenage boys who had been labeled as juvenile delinquents to see how they either embraced or denied these labels. They argued that criminals don’t have vastly different cultural values but rather adopt attitudes to justify criminal behavior. Sykes and Matza developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts. Individuals may not necessarily internalize labels if they have developed strategies to reject associating their actions with these labels.

Let’s apply each of these techniques by pretending to be a teenager justifying shoplifting at a major retail chain department store. From this example, we can see how individuals can justify engaging in an act that may be illegal and violates social norms through these kinds of cognitive strategies

- The denial of responsibility: rejecting a label because it’s not their fault

Example: “I don’t want to steal from this store, but I’ve applied to so many jobs, and no one seems to want to hire a teenager these days.” - The denial of injury: judging a situation based on its effect on others

Example: “It’s not like anyone is being hurt by me stealing.” - The denial of the victim: no victim, no crime

Example: “Who am I hurting anyway? This is a big corporation! They expect some level of theft.” - The condemnation of the condemners: shifting the narrative away from the deviant behavior to critique by blaming individuals who may hold you accountable or who are impacted

Example: “This corporation is way more corrupt considering the fact most of their goods come from sweatshops that use child labor. - The appeal to higher loyalty: actions were for a higher or more significant purpose

Example: “I’m only stealing because I really don’t have enough money to get my sister a nice birthday present, and she matters way more to me than any stupid corporation does. I’m a modern-day Robin Hood.”

Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behavior developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology, including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006) and the work of George Herbert Mead, whose ideas are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4. His conclusions established differential association theory, which suggested that individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance.

According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. He argues that people learn all aspects of criminal behavior through interacting with others and being part of intimate personal groups. Sutherland’s theory captures not only how people learn criminal behavior, but also how people learn motives, rationalizations, and attitudes toward crime.

Differential association theory also demystifies crime, conceptualizing it as a behavior just like any other. This is a radical departure from early theories of crime, which viewed criminals as inherently, biologically different. In Sutherland’s theory, anyone has the potential to engage in crime if they learn how to commit crime and embrace favorable definitions of crime. This theory also helps explain why not all people who grow up in poverty engage in criminal activity, as historical theories such as cultural deviance theory suggest. Rather, they encounter different situations that shape their definitions of violating the law.

Feminist Theories of Deviance and Crime

Feminists point out how most of the preceding theories of deviance and crime we have explored tend to focus primarily on men. In response, feminists argue that scholars should address and explain women offenders, women victims, and the experiences of women with the criminal justice system (Lempert 2016). One influential feminist theorist of deviance and crime is British sociologist Frances Mary Heidensohn. She argued that sociologists have failed to explain the deviance of women while centering their analysis on men. This is problematic since women make up around half of any human society. Further, she pointed out that there might be distinct differences in how men and women are deviant (Heidensohn 1968).

For a summary of all the theories covered in this section, check out figure 7.6.

| Theory | Associated Theorist | Contribution to the Study of Deviance and Crime |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Association Theory | Edwin Sutherland | Argues that deviance arises from learning and modeling deviant behavior seen in other people close to the individual |

| Discipline and Punishment Theory | Michel Foucault | Highlights how social control mechanisms are not just formal sanctions, but also built into modern institutions |

| Labeling Theory | Edwin Lemert | Argues that deviance arises from the reactions of others, particularly those in power who are able to determine labels |

| Revised Social Disorganization Theory | William Julius Wilson | Argues that crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high-crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement |

| Strain Theory | Robert Merton | Argues that deviance arises from a lack of ways to reach socially accepted goals using accepted methods |

| Techniques of Neutralization | Gresham Sykes and David Matza | Developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts |

| Feminism | Frances Mary Heidensohn | Turned attention to how gender impacts crime and deviance; focuses on the experiences of women offenders and victims |

Activity: Applying Theories of Deviance to Public Events

Exposing one’s genitals in public is a behavior that is typically met with negative sanctions and consequences. Though it varies by state, most states have laws prohibiting indecent exposure. However, these rules and norms shift when nudity is used as a form of free speech and protest. Portland’s World Naked Bike Ride provides us with an opportunity to analyze our social norms and think through how different theoretical perspectives may view a naked bike protest (figure 7.7).

First, visit the following websites to learn more about Portland’s World Naked Bike Ride [Website] and pdxwnbr [Website]. After reviewing the websites, come back and answer the following questions:

- What is the goal of Portland’s World Naked Bike Ride?

- Select three theories of deviance discussed in this chapter. Explain how each theory would analyze the actions of participants in the event.

- Which theory of deviance do you think best explains this event? Why?

- What theory of deviance is useful in understanding why people participate in protests?

Licenses and Attributions for Modern Theories of Deviance

Open Content, Original

“Feminist Theories of Deviance and Crime” and “Activity: Applying Theories of Deviance to Public Events” by Jennifer Puentes and Matthew Gougherty are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Modern Theories of Deviance” by Alexandra Olsen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Robert Merton’s Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity. Examples added.

“Lemert’s Labeling Theory” paragraphs one and two, and sentences one and two in paragraph three edited for clarity and brevity from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and clarity.

Figure 7.5. “Panopticon” by Jeremy Bentham is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.6. From “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Substantial modifications and additions have been made.

Figure 7.7. “Naked Bike Ride 2013” by drburtoni is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

a violation of contextual, cultural, or social norms.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

a theory that addresses the relationship between having socially acceptable goals and having socially acceptable means to reach those goals.

a theory that asserts crime occurs in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control.

a behavior that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the regulation and enforcement of norms.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

a micro-level theory that emphasizes the importance of meanings and interactions in social life.

the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society.

a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

a person’s distinct identity that is developed through social interaction.

deviance that occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after his or her actions are labeled as deviant by members of society.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

shared beliefs about what a group considers worthwhile or desirable.

the scientific and systematic study of groups and group interactions, societies and social interactions, from small and personal groups to very large groups and mass culture; also, the systematic study of human society and interactions.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

a theory that states individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance.

the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values.

an organization that exists to enforce a legal code, which in the United States includes the police, courts, and corrections system.