9.4 Examining Interactions

Applying the framework of symbolic interactionism to gender, we have an opportunity to see how the meanings associated with gender categories are produced through the process of interaction. “Doing gender” is a phrase developed by sociologists Candace West and Don Zimmerman (1987). The phrase and concept continue to be built on by other scholars, but at its core, it refers to the idea that individuals perform gender based on the way that gender is socially constructed within their society. We accomplish or “do” gender in our daily lives through our interactions with others and how we speak and think about gender, including the “rules” of gender that we may choose to follow or challenge.

Although we have agency to construct performances and engage in behaviors that are gender conforming or nonconforming, we are often held accountable for accomplishing certain “accepted” presentations of gender (West and Zimmerman 1987). Others expect people to engage in gendered performances, and they contribute to why we think about gendered behavior as “natural.” In this section, you will learn more about how gender is socially constructed and learned through the process of socialization and the policing of behaviors. We will explore the idea that some performances and embodiments of masculinity and femininity may be more highly valued in different contexts. Finally, we will explore how gender intersects with other identities, such as race, class, and sexuality.

Socialization

Sociologists tend to view socialization as a lifelong process of learning and re-learning gendered expectations. Part of this learning process requires that we continually adjust to new contexts. As we age, travel, and experience new contexts we continue to learn about gender. This model of socialization explains how the “rules” of gender can change over time and how we are able to show agency, or personal control, in resisting gender rules.

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each of these reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining expectations of what is normal for gender-specific behavior. Gender socialization also happens in other places, such as religious institutions and the workplace. Over time, these agents lead people into a false sense that they are acting naturally rather than following a socially constructed role. In this section, we will focus primarily on the role of families in socialization.

Family is the first agent of socialization we come into contact with. Evidence shows that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. Generally speaking, girls are given more permission to step outside of traditionally feminine roles (Coltrane and Adams 2004; Kimmel 2000; Raffaelli and Ontai 2004). However, the different ways that girls and boys are socialized tend to result in more privileges for boys (figure 9.9). For instance, boys are allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age than daughters. They may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfews. Sons are also often free from cleaning or cooking and other household tasks that are considered feminine. Daughters are limited by their expectation to be obedient, passive, and nurturing. They are expected to take on many of the domestic responsibilities.

For example, something as simple as who is expected to participate in certain household chores can vary by gender. Figure 9.10 depicts a father and son maintaining the lawn, a household task that is typically completed a few times a month, while figure 9.11 shows a mother and daughter preparing a meal in the kitchen, a chore that is completed daily.

Children tend to absorb everything around them and quickly learn about gender stereotypes. They may align themselves to certain toys as they look for parental praise. However, children are active participants in their socialization, and they may challenge gender expectations with what they know (or think they know). Children often actively participate in peer socialization when it comes to gender and help establish some “rules” about what is “right” through rigid policing (Messner 2000; Thorne 1993).

Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be asked to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel 2000). Parental socialization and normative expectations also vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. African-American families, for instance, are more likely than Whites to model an egalitarian role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson 2004).

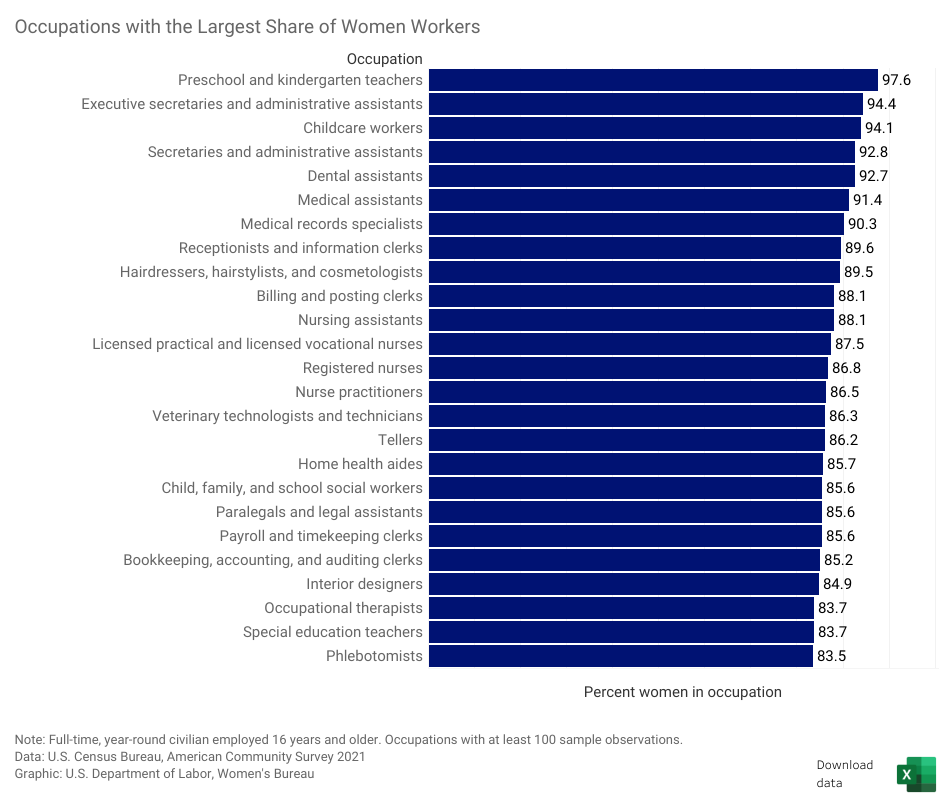

The drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles continues later in life, a tendency sometimes referred to as “occupational sorting” (Gerdeman 2019). Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics. Women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare (even though the term “doctor” still conjures the image of a man), and social work (figure 9.12). These occupational roles are examples of typical U.S. male and female behavior, derived from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to these roles demonstrates fulfillment of social expectations but not necessarily personal preference (Diamond 2002). Sometimes, people work in a profession because of societal pressure and/or the opportunities afforded to them based on their gender.

Historically, women have had difficulty shedding the expectation that they cannot be a “good mother” and a “good worker” at the same time, which results in fewer opportunities and lower levels of pay (Ogden 2019). Generally, men do not share this difficulty. Since the assumed role of men as fathers does not seem to conflict with their perceived work role, men who are fathers (or who are expected to become fathers) do not face the same barriers to employment or promotion (González 2019). This is sometimes referred to as the “motherhood penalty” versus the “fatherhood premium” and is prevalent in many higher-income countries (Bygren 2017).

Gender Policing

Socialization is a powerful force that is ongoing and occurs through many social institutions, such as education, mass media, and government. Considering that we have agency or free will to behave as we want, you might be wondering why so many of us follow gender rules. Often, we follow gender rules out of habit, pleasure, and out of concern for how we will be viewed by others (Wade and Ferree 2015). Gender rules become part of our culture, and we often participate in gendered practices unconsciously. In public spaces, men tend to take up more physical space than women. Figure 9.13 illustrates how the way we take up space in public is gendered. The man, with his legs spread wide apart appears to be taking up space on the woman’s seat.

We may receive pleasure when we enact forms of masculinity and femininity that are expected of us given our genders. Quinceañeras, high school proms, and weddings all provide us with opportunities to elaborately participate in gendered displays—most often suits or tuxedos for men and dresses or gowns for women. Many people enjoy these events and invest a great deal of time, energy, and money into them.

Finally, the reactions we receive from others regarding our gender performances shape our behavior. As you learned in Chapter 4, we are often expected to conform to social norms or normative behaviors. In many cultures, this means conforming to binary expressions, which leads to gender inequality (figure 9.14). However, members of a society are strongly invested in maintaining the existing gender order and thus engage in “gender policing” to remind people of the rules of “doing” gender (Zellavos 2014). Typically, violating gender rules will lead to negative attention, which acts to reinforce the rules of gender. Consequences for violating gender rules can range from friendly, humorous teasing to more brutal and painful reactions.

Let’s look at an example from the research of American sociologist, Catherine Connell (2010), who applied West and Zimmerman’s concept of “doing gender” to see the extent to which gender could be undone in a professional context where transgender people worked. She aimed to study if transgender people challenge how gender is “done” through their jobs and work relationships. As part of her research, Connell conducted in-depth interviews with 19 transgender people. Five of the participants were in “stealth mode” in their workplace, meaning they did not identify themselves as a transgender person. They saw their gender was private, and they had no desire to share this information with work colleagues. The other 14 participants had “come out” as transgender to work colleagues.

Connell found that male-to-female transgender people put a lot more work into doing gender after their transition. The transgender women talked about taking a lot more time and care in thinking about their outfits and putting on makeup. The female-to-male transgender men reported the opposite. One transgender man talked about life being easier, with less time spent on grooming. These people were acknowledging how “doing gender” happens. Society expects women to put a lot of time into their appearance, but the same expectation is not placed on men (and yes, this is changing, but the imbalance still places women under more scrutiny).

The participants in Connell’s study found that their colleagues were constantly giving them advice about how to do gender “properly”—how to dress, how to behave, how not to behave. Even though some of their colleagues were supportive, others expressed reservations about how gender reassignment might affect their employees. One computer programmer who transitioned from male to female said that her boss was afraid she wouldn’t be able to do programming as well. In this respect, the transgender women felt devalued in their workplace after their transition, and they adopted what they saw as masculine traits to gain back respect. This included being “more aggressive” during meetings. For example, they might raise their voice, bang on the table, and adopt other “more assertive” behavior.

The risks of nonconformity can be high. More than being perceived as “weird” or unpopular, we may lose the support of friends and family or even experience discrimination in the workplace based on our gender presentation. It might be difficult to imagine blatant gender inequality today, considering the progress made by women’s rights movements over the past several decades. However, despite being a numerical majority, women still hold a minority position in society. This means that women (as well as others who are members of minority groups) hold less power and experience unequal treatment in society. For example, men can take up more physical space compared to women and are less likely to be interrupted when speaking.

Inequalities emerge through sexism, the belief that some individuals or groups are superior to others based on sex or gender. Sexism connects with the concepts of prejudice and discrimination. Prejudice refers to a set of strongly held beliefs or attitudes about the characteristics of a group that are unlikely to change, even when evidence challenges those beliefs. Prejudices are difficult to change because they are often rooted in stereotypes that are part of our shared culture. Discrimination refers to behaviors or actions that create unequal treatment for individuals or groups because of their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex) by limiting access to social resources (e.g., education, housing, jobs, legal rights, loans, or political power). Prejudice and discrimination can be based on sexual orientation, gender expression, and gender identity, which you will learn more about in Chapter 10.

Licenses and Attributions for Examining Interactions

Open Content, Original

“Examining Interactions” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Socialization” paragraphs three, four, and seven through nine are from “12.2 Gender and Gender Inequality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, OpenStax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency, clarity, and brevity.

“Gender Role” definition modified from “Ch. 12 Key Terms” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Gender Policing” paragraphs four through six from “Transgender Women’s Experiences of Gender Inequality at Work” by Zuleyka Zevallos in The Other Sociologist, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Edited for consistency and brevity; all other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.9. “UNITED STATES – CIRCA 1950s: Two girls walking along suburban street” by Unsplash collaboration with Getty Images is licensed under the Unsplash+ License.

Figure 9.10. ”AJ and Daddy on Father’s Day” by hose902 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 9.11. “Women cooking foods, Vietnam, 1969” by manhai is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.13. “Manspreading on Stockholm Metro” by Peter Isotalo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.14. “Gender Policing” by Zuleyka Zevallos is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.12. “Occupations with the largest share of women workers” by U.S. Department of Labor is in the Public Domain.

a term that refers to the behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male

the idea that individuals perform gender based on the way that gender is socially constructed within their society; they are held accountable for enacting gendered behaviors. These gendered performances are expected and contribute to why we think of gendered behavior as “natural.”

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, interact with one another, and share a common culture.

freewill or the ability to make independent decisions. As sociologists, we understand that the choices we have available to us are often limited by larger structural constraints.

the process wherein people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values.

a category of identity that ascribes social, cultural, and political meaning and consequence to physical characteristics.

a set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have toward other people.

individuals or institutions that socialize people.

patterns of behavior that are representative of a person’s social status.

categories of difference organized around shared language, culture and faith tradition.

a person’s wages or investment dividends. Earned on a regular basis.

mechanisms or patterns of social order focused on meeting social needs, such as government, the economy, education, family, healthcare, and religion.

the social expectations of how to behave in a situation.

the practice of judging people’s gender practices and reminding others of the rules of “doing gender.” This practice reinforces gender order and reproduces gender inequality.

a person whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not necessarily the same.

one-on-one conversations with participants designed to gather information about a particular topic.

actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories.

the belief that some individuals or groups are superior to others based on sex or gender.

physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity.

the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience.

any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share some sense of aligned identity.

enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender.

a deeply held internal perception of one’s gender.