Nutrition in Pregnancy and Lactation

Physiology of Pregnancy

Human pregnancy lasts for approximately 40 weeks (when counted from the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period) and is roughly divided into thirds, or trimesters. Dramatic changes occur throughout pregnancy, including in the earliest days, sometimes before women realize they’re pregnant. Therefore, adequate nutrition is vital for women who are trying to conceive or may become pregnant. In addition, women who are either underweight or obese before becoming pregnant can find it more difficult to get pregnant and face greater risks of pregnancy complications. Therefore, it’s recommended to establish healthy eating and exercise habits and work towards a healthy weight before pregnancy.1 Nutrition before conception is also important for fathers; studies have shown that sperm quality is better in fathers who have a healthy body weight, consume adequate amounts of folate and omega-3 fatty acids, and follow a healthy dietary pattern, such as a Mediterranean diet emphasizing seafood, poultry, whole grains, legumes, and fruits and vegetables.2

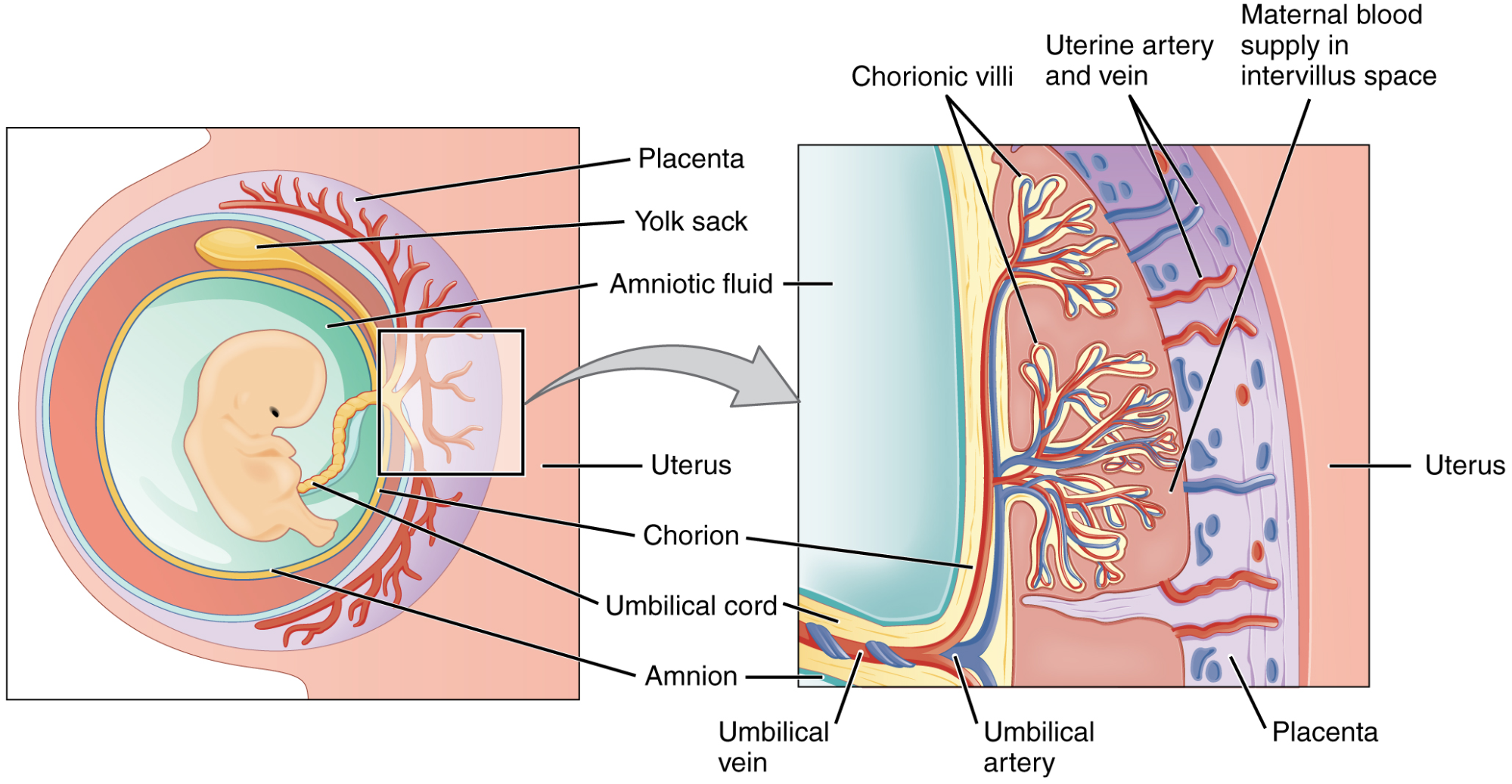

Pregnancy begins when the sperm fertilizes the egg, and the single cell formed from this union begins to divide and differentiate. During the first few weeks of development, the cells of the uterine lining provide nutrients to the developing embryo. Between the 4th and 12th weeks, the developing placenta gradually takes over the role of feeding the embryo, which is called a fetus beginning in the 9th week of pregnancy. The placenta forms from tissues deriving from both the fetus and the mother, and this new organ becomes the interface between the two. The placenta provides nutrition and respiration, handles waste from the fetus, and produces hormones important to maintaining the pregnancy. The blood of the fetus and mother do not mix in the placenta, but they come close enough that nutrients (including glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals) and oxygen can pass from the mother’s blood to the fetus, and carbon dioxide and waste products can be passed from the fetus to the mother.3

Figure 11.1. Cross-section of the placenta. In the placenta, the maternal and fetal bloodstreams do not mix, but nutrients, gasses, and waste products can diffuse between them.

The first trimester is a key period for the formation of embryonic and fetal organs. During the second and third trimesters, the fetus continues to grow and develop, with final development of organs such as the brain, lungs, and liver continuing in the last few weeks of pregnancy. Infants born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are considered preterm, and because they have not completed fetal development, are at increased risk for a range of health problems. Advances in neonatal care have greatly improved outcomes for these babies born too soon, but in most cases, the best scenario is for the fetus to have the full term of pregnancy to develop in the protective environment of the uterus, receiving nutrients through the placenta.4

Nutrient Requirements During Pregnancy

Pregnant women need more calories, macronutrients, and micronutrients than they did before pregnancy. However, the increase in nutrient requirements is relatively greater than the increase in caloric needs, emphasizing the importance of a nutrient-dense diet. A dietary pattern focused on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, legumes, fish, and vegetable oils, and lower in red and processed meats, refined grains, and added sugars is associated with a reduced risk of pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes and hypertension.5 There is nothing revolutionary about this dietary pattern—it’s what is recommended for everyone! However, it’s even more beneficial during pregnancy, as it promotes both maternal and fetal health.

Energy Intake and Weight Gain

During the first trimester, energy requirements are generally not increased, so women should consume about the same number of calories as they did before pregnancy. As fetal growth ramps up, energy requirements increase by about 340 calories per day in the second trimester and 450 calories per day in the third trimester. This is just an average; individual energy requirements vary depending on factors such as activity level and body weight before pregnancy.6-7

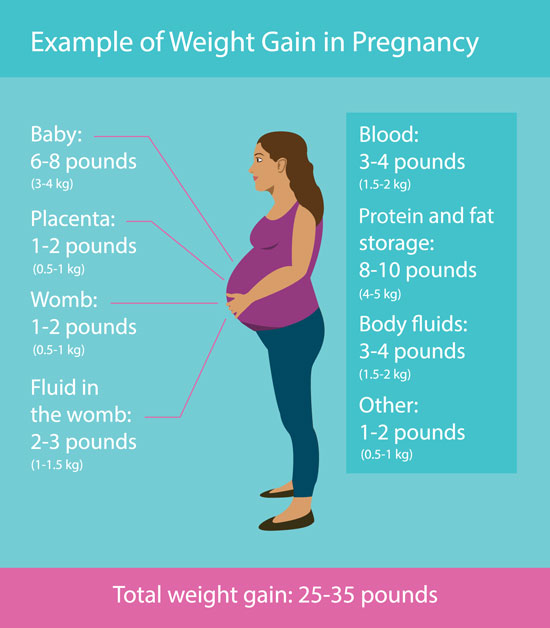

Weight gain is a normal part of pregnancy. The growth of the fetus accounts for about 6 to 8 pounds of weight gain by the end of the pregnancy. Much of the rest comes from the development and expansion of tissues and fluids to support the pregnancy, including the placenta, uterus, breasts, amniotic fluid, blood, and maternal body fluids. In addition, women starting pregnancy at a normal weight should gain about 8 to 10 pounds of body fat and protein during pregnancy, in part to prepare for lactation.3

Figure 11.2. Components of weight gain in healthy pregnant women with normal BMI before pregnancy. Weight gain comes not just from the baby, but from many different body systems changing to support the pregnancy.

The Institute of Medicine recommends different amounts of weight gain in pregnancy depending on pre-pregnancy BMI. Women who were underweight before pregnancy need to gain more, and those who were overweight or obese before pregnancy need to gain less. Gaining too little weight in pregnancy can compromise fetal growth, leading to the baby being born too small, which can cause increased risk of illness, difficulty feeding, and developmental delays. Gaining too much weight in pregnancy can cause the baby to be too big at birth, leading to birth complications and increasing the risk of needing a cesarean birth. It can also make it more difficult to lose weight after pregnancy.8

|

Prepregnancy Weight Category |

Body Mass Index (BMI) |

Recommended Range of Total Weight Gain (lb) |

Recommended Rates of Weight Gain in the 2nd and 3rd Trimesters (lb/wk) |

|

Underweight |

Less than 18.8 |

28-40 |

1 (1-1.3) |

|

Normal weight |

18.5-24.9 |

25-35 |

1 (0.8-1) |

|

Overweight |

25-29.9 |

15-25 |

0.6 (0.5-0.7) |

|

Obese |

30 and greater |

11-20 |

0.5 (0.4-0.6) |

Table 11.1. Recommended weight gain during pregnancy depends on prepregnancy BMI.7

Exercising during pregnancy can promote the health of both the mother and the baby. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, regular exercise in pregnancy can reduce back pain, ease constipation, promote healthy weight gain, improve overall fitness, and help with weight loss after the baby is born. It may also decrease the risk of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. ACOG recommends that pregnant women get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week. Most forms of exercise are safe in pregnancy; women should consult their healthcare provider for individualized advice about exercising while pregnant.9

Macronutrient Requirements

The Acceptable Macronutrient Distributions Ranges (AMDR) for macronutrients are the same for all healthy adults, pregnant or not, with about 45 to 65 percent of calories coming from carbohydrates, 20 to 35 percent from fats, and 10 to 35 percent from protein. As energy intake increases, a pregnant woman needs more of each of these macronutrients.

The RDA for carbohydrates increases from 130 grams per day for non-pregnant adults to 175 grams per day for pregnant women. This level of carbohydrate intake provides energy for fetal development and ensures adequate glucose for both the mother’s and the fetus’s brain. The recommended fiber intake in pregnancy, expressed as an AI, is the same as for all adults: 14 grams of fiber per 1,000 calories consumed. As caloric intake increases during pregnancy, so should fiber intake, emphasizing the importance of choosing whole food sources of carbohydrates.

Additional protein is also needed during pregnancy. Protein builds muscle and other tissues, enzymes, antibodies, and hormones in both the mother and the fetus, as well as supporting increased blood volume and the production of amniotic fluid. The RDA for protein during pregnancy is 1.1 grams per kg body weight per day, coming to about 71 grams per day for an average woman—roughly 25 grams more than needed before pregnancy.1

There is not a specific RDA for fat during pregnancy. Fats should continue to make up 25 to 35 percent of daily caloric intake, providing energy and essential fatty acids (linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid), as well as helping with fat-soluble vitamin absorption. The omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids DHA and EPA become more important during pregnancy and lactation, because they are essential for brain and eye development of the fetus and infant. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that pregnant women consume 8 to 12 ounces of seafood each week, in part to provide omega-3 fatty acids. Fish with high levels of mercury should be avoided; these include king mackerel, marlin, orange roughy, shark, swordfish, tilefish, and bigeye tuna.11-12

Figure 11.3. Advice from the EPA and FDA about choosing safe fish to consume during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

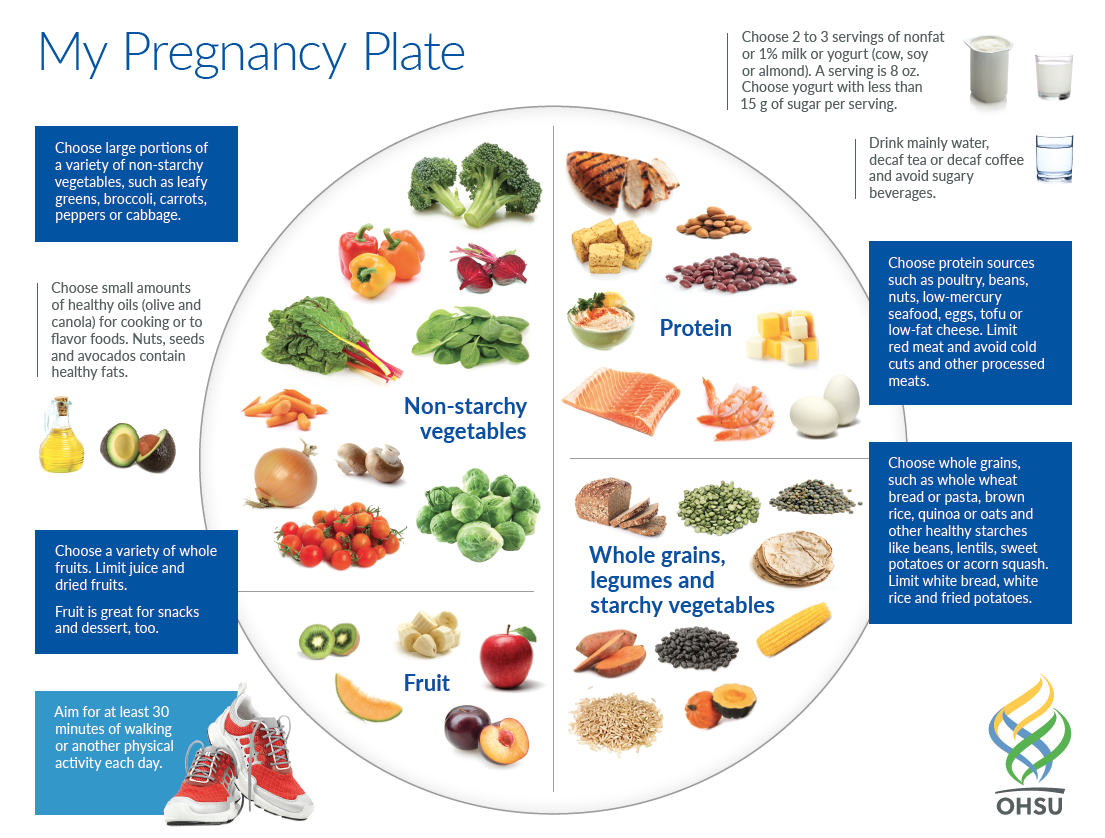

Consider the following recommendations for healthy eating during pregnancy, as summarized in the My Pregnancy Plate graphic:

- Choose large portions of a variety of non-starchy vegetables such as leafy greens, broccoli, carrots, bell peppers, tomatoes, mushrooms, and cabbage.

- Choose a variety of whole fruits, limiting juice and dried fruit.

- Aim for 2 to 3 servings of nonfat or 1 percent milk or yogurt (unsweetened or slightly sweetened).

- Choose protein sources like poultry, beans, nuts, eggs, tofu, and cheese. Aim for 8 to 12 ounces of low-mercury seafood each week.

- Choose fiber-rich sources of carbohydrates, including whole grains, legumes, and starchy vegetables such as sweet potatoes and squash.

- Drink mainly water, decaf coffee, or tea. (Caffeine is discussed below).

Figure 11.4. The My Pregnancy Plate graphic summarizes dietary recommendations for pregnancy. Source: Created by Christie Naze, RD, CDE, ©Oregon Health & Science University, used with permission.

Vitamin and Mineral Requirements

The physiological demands of pregnancy increase the requirement for many vitamins and minerals. These requirements can be met from food sources, but obstetricians also generally recommend that women take a prenatal supplement while trying to conceive and during pregnancy. This ensures that nutrient requirements are met, while also providing a little peace of mind if pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting limit dietary variety and quality.1

The following table compares the recommended intake levels of some vitamins and minerals to the levels needed in pregnancy.

|

Nutrient |

RDA/AI, Nonpregnant Adult Women |

RDA/AI, Pregnant Adult |

Importance |

|

Vitamin A |

700 mcg |

770 mcg |

Forms healthy skin and eyesight; helps with bone growth |

|

Vitamin B6 |

1.3 mg |

1.9 mg |

Helps form red blood cells; helps the body metabolize macronutrients |

|

Vitamin B12 |

2.4 mcg |

2.6 mcg |

Maintains nervous system; helps form red blood cells |

|

Vitamin C |

75 mg |

85 mg |

Promotes healthy gums, teeth, and bones |

|

Vitamin D |

600 IU |

600 IU |

Builds fetal bones and teeth; promotes healthy eyesight and skin |

|

Folate |

400 mcg |

600 mcg |

Helps prevent neural tube defects; supports growth and development of fetus and placenta |

|

Calcium |

1,000 mg |

1,000 mg |

Builds strong bones and teeth |

|

Iron |

18 mg |

27 mg |

Helps red blood cells deliver oxygen to fetus |

|

Iodine |

150 mcg |

220 mg |

Essential for healthy brain development |

|

Choline |

425 mg |

450 mg |

Important for development of fetal brain and spinal cord |

Table 11.2. Recommended Micronutrient intakes during pregnancy. Sources: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements.

Among the micronutrients, folate, iron, and iodine deserve a special mention. Folate is essential for the growth and specialization of cells of the central nervous system (see Unit 9). Mothers who are folate-deficient during pregnancy have a higher risk of having a baby with a neural tube birth defect such as spina bifida. Folic acid fortification of grains in the U.S. has helped to raise folate intake in the general population and has reduced the incidence of neural tube defects. However, dietary intake is often not adequate to meet the requirement of 600 mcg folate per day in pregnancy, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that pregnant women take an additional 400 mcg of folic acid each day, an amount usually included in prenatal supplements.13 The neural tube closes by day 28 of pregnancy, before a woman may realize she is pregnant, so it’s important to consume adequate folate while trying to conceive. Because about 45 percent of pregnancies in the U.S. are unplanned, a folic acid supplement is a good idea for anyone who may become pregnant.14

Iron intake is important because of the increase in blood volume during pregnancy. Iron is an essential component of hemoglobin, the protein responsible for oxygen transport in blood, so adequate iron intake supports oxygen delivery to both maternal and fetal tissues (see Unit 9). Good dietary sources of iron include meat, poultry, seafood, nuts, legumes, and fortified or whole grain cereals. Iron should also be included in a prenatal supplement or taken separately.

Iodine is essential for fetal brain development, but recent data suggests that many pregnant women in the U.S. do not consume enough iodine to meet their increased requirement.15 Much of the iodine in the typical American diet comes from dairy products and iodized salt. However, iodine intake in the U.S. has declined in recent decades as more people watch their intake of table salt and/or switch to kosher or sea salt, which aren’t iodized. In addition, processed foods are generally made with non-iodized salt, and the intake of processed foods has increased. Meanwhile, the popularity of dairy products has declined. Most people in the U.S. still consume enough iodine to meet their requirement, but pregnant women may be at risk for iodine deficiency because of their increased need for this mineral. Iodine deficiency during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, and major neurodevelopmental deficits and growth retardation in the fetus.16 Unfortunately, many prenatal vitamins do not contain iodine, so it’s worth checking the label to ensure that iodine is included.17

The micronutrients involved with building the skeleton—vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium—are crucial during pregnancy to support fetal bone development. Although the levels are the same as those for nonpregnant women, many women do not typically consume adequate amounts and should make an extra effort to meet those needs.

As always, it’s important to read supplement labels carefully, with the aim of choosing a prenatal supplement that contains close to the RDA or AI for micronutrients and avoiding those that exceed the UL, unless under the specific direction of a healthcare provider. In particular, both vitamin A and zinc consumed in excessive amounts can cause birth defects. Beta-carotene is typically used as the vitamin A source in prenatal supplements, because unlike vitamin A, it doesn’t cause birth defects (see Unit 8).

Foods and Other Substances to Avoid

It’s not just nutrients that can cross the placenta. Other substances such as alcohol, nicotine, cannabinoids (from cannabis), and both prescription and recreational drugs can also pass from mother to fetus. Exposure to these substances can have lasting and detrimental effects on the health of the fetus. For this reason, pregnant women are advised to avoid using alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and recreational drugs during pregnancy. Medical providers can help pregnant women quit using these substances and advise them on the safety of specific medications needed during pregnancy.1

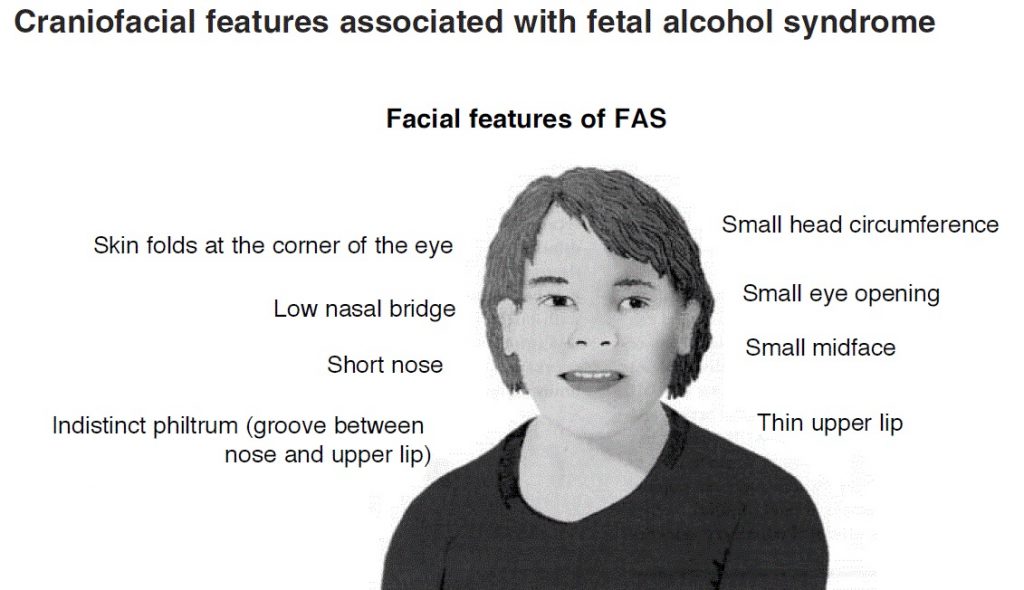

Some substances are so detrimental that a woman should avoid them even if she suspects that she might be pregnant. For example, consumption of alcoholic beverages results in a range of abnormalities that fall under the umbrella of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. They include learning and attention deficits, heart defects, and abnormal facial features (Figure 11.5). Alcohol enters the fetus’s bloodstream via the umbilical cord and can slow fetal growth, damage the brain, or even result in miscarriage. The effects of alcohol are most severe in the first trimester, when the organs are developing. There is no known safe amount of alcohol in pregnancy.

Figure 11.5. Craniofacial features associated with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Caffeine use should be limited to less than 200 milligrams per day, or the equivalent of about two cups of coffee. Consumption of greater amounts is linked to miscarriage and preterm birth. Keep in mind that caffeine is also found in other sources such as chocolate, energy drinks, soda, tea, and some over-the-counter pain and headache medications.1

It’s also important to pay special attention to avoiding foodborne illness during pregnancy, as it can cause major health problems for both the mother and the developing fetus. For example, the foodborne illness caused by the bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, called listeriosis, can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, and fetal or newborn meningitis. According to the CDC, pregnant women are ten times more likely to become ill with this disease than nonpregnant adults, likely because they have a dampened immune response.19 Other common foodborne illnesses, such as those caused by Salmonella and E. coli, can also be very serious in pregnant women.

Foods more likely to be contaminated with foodborne pathogens should be avoided by pregnant women to decrease their chances of infection. These include the following:20

- Unpasteurized dairy products such as soft cheeses

- Raw or smoked seafood

- Hot dogs and deli meats (or heat to 165° before eating)

- Paté and other meat spreads

- Undercooked or raw meat, poultry, and eggs

- Raw sprouts

- Raw dough

- Unpasteurized juice and cider

Following standard food safety practices can also go a long way towards preventing foodborne illness, during pregnancy or anytime. The CDC offers this summary of food safety tips:

- COOK. Use a food thermometer to ensure that foods are cooked to a safe i

nternal temperature: 145°F for whole beef, pork, lamb, and veal (allowing the meat to rest for 3 minutes before carving or consuming), 160°F for ground meats, and 165°F for all poultry, including ground chicken and turkey.

nternal temperature: 145°F for whole beef, pork, lamb, and veal (allowing the meat to rest for 3 minutes before carving or consuming), 160°F for ground meats, and 165°F for all poultry, including ground chicken and turkey. - CLEAN. Wash your hands after touching raw meat, poultry, and seafood. Also wash your work surfaces, cutting boards, utensils, and grill before and after cooking.

- CHILL. Keep your refrigerator below 40°F and refrigerate foods within 2 hours of cooking (1 hour during the summer heat).

- SEPARATE. Germs from raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs can spread to produce and ready-to-eat foods unless you keep them separate. Use different cutting boards to prepare raw meats and any food that will be eaten without cooking.

Maternal Health During Pregnancy

Especially during the first trimester, it’s very common for women to feel nauseous, often leading to vomiting, and to be very sensitive to smells. This so-called “morning sickness” is misnamed, because it can make women feel awful any time of day—morning, noon, and night. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy affects as many as four out of five pregnancies. Symptoms can range from mild nausea to a much more severe illness called hyperemesis gravidarum, which causes relentless vomiting and affects between 0.3 and 3 percent of all pregnancies. Most women find that their nausea and vomiting subsides by the end of the first trimester, but in rare and unfortunate cases, it can continue until the baby is born.21

Dietary changes can help alleviate nausea and vomiting. Here are some suggestions:22

- Choose foods that are low in fat and easily digestible, such as those in the BRATT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast, and tea). The goal is simply to find foods that can be tolerated. It is reassuring to remember that pregnancy does not require extra calories during the first trimester, and a prenatal supplement can help meet micronutrient needs.

- An empty stomach can worsen feelings of nausea, so try eating a few crackers or dry toast before getting out of bed in the morning to avoid moving around with an empty stomach. It may also help to eat five or six small meals per day and to eat small snacks such as crackers, fruits, and nuts throughout the day.

- Many pregnant women experiencing nausea and vomiting find meat unappetizing. Try other sources of protein such as dairy foods (e.g., milk, yogurt, ice cream), nuts and seeds (as well as nut butters), and protein powders and shakes.

- Ginger can help settle your stomach; it’s available in capsule, candy, and tea form. Ginger ale, if made with real ginger, might also be helpful.

If nausea and vomiting remain unmanageable after making these dietary changes, medications may be necessary. Hyperemesis gravidarum, though rare, can be very serious. Constant vomiting can lead to malnutrition, weight loss, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. Hospitalization may be required so that women can receive fluids and electrolytes through an intravenous line, and sometimes a feeding tube is necessary. Getting help for this condition can be a frustrating process of trial-and-error, and unfortunately, there are still many unknowns about its causes and effective treatment options.23

As pregnancy progresses, another common complaint is heartburn, caused by gastroesophageal reflux. This is caused by the upward, constrictive pressure of the growing uterus on the stomach, as well as decreased peristalsis in the GI tract. (See Unit 3 for management strategies.)

About 6 percent of pregnancies in the U.S. are affected by gestational diabetes (see Unit 4).24 This is a type of diabetes that develops during pregnancy in women who didn’t previously have diabetes. Gestational diabetes is managed by monitoring blood glucose levels, eating a healthy diet, and exercising regularly. Sometimes, insulin injections are needed. If blood glucose levels aren’t well controlled in the mother, the fetus will also have high blood glucose levels. This can cause the baby to grow too big, leading to a greater chance of birth complications and increased likelihood of needing a cesarean birth.25

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program. (2018). Lifespan Nutrition From Pregnancy to the Toddler Years. In Human Nutrition http://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Chapter 28: Development and Inheritance. In

Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/28-2-embryonic-development, CC BY 4.0

References:

- 1American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(1), e78-89.

- 2Nassan, F. L., Chavarro, J. E., & Tanrikut, C. (2018). Diet and men’s fertility: Does diet affect sperm quality? Fertility and Sterility, 110(4), 570–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.05.025

- 3Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Embryonic Development. In Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/28-2-embryonic-development

- 4CDC. (2019). Preterm Birth. Reproductive Health. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm

- 5Raghavan, R., Dreibelbis, C., Kingshipp, B. L., Wong, Y. P., Abrams, B., Gernand, A. D., Rasmussen, K. M., Siega-Riz, A. M., Stang, J., Casavale, K. O., Spahn, J. M., & Stoody, E. E. (2019). Dietary patterns before and during pregnancy and maternal outcomes: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(Supplement_1), 705S-728S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy216

- 6Kominiarek, M. A., & Rajan, P. (2016). Nutrition Recommendations in Pregnancy and Lactation. The Medical Clinics of North America, 100(6), 1199–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.06.004

- 7Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). The National Academies Press.

- 8American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2013). Weight Gain During Pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 548. Reaffirmed 2020. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 121, 210–212.

- 9American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Exercise During Pregnancy. Patient Resources. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://www.acog.org/en/Patient Resources/FAQs/Pregnancy/Exercise During Pregnancy

- 10Lowensohn, R. I., Stadler, D. D., & Naze, C. (2016). Current Concepts of Maternal Nutrition. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 71(7), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000329

- 11Hibbeln, J. R., Spiller, P., Brenna, J. T., Golding, J., Holub, B. J., Harris, W. S., Kris-Etherton, P., Lands, B., Connor, S. L., Myers, G., Strain, J. J., Crawford, M. A., & Carlson, S. E. (2019). Relationships between seafood consumption during pregnancy and childhood and neurocognitive development: Two systematic reviews. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids, 151, 14–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2019.10.002

- 12U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, 9th Edition. Retrieved from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

- 13American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Nutrition During Pregnancy. Retrieved August 9, 2020, from https://www.acog.org/en/Patient Resources/FAQs/Pregnancy/Nutrition During Pregnancy

- 14Finer, L. B., & Zolna, M. R. (2016). Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(9), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1506575

- 15Council on Environmental Health, Rogan, W. J., Paulson, J. A., Baum, C., Brock-Utne, A. C., Brumberg, H. L., Campbell, C. C., Lanphear, B. P., Lowry, J. A., Osterhoudt, K. C., Sandel, M. T., Spanier, A., & Trasande, L. (2014). Iodine deficiency, pollutant chemicals, and the thyroid: New information on an old problem. Pediatrics, 133(6), 1163–1166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0900

- 16National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Iodine—Fact Sheet for Health Professionals [Office of Dietary Supplements]. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iodine-HealthProfessional/

- 17Patel, A., Lee, S. Y., Stagnaro-Green, A., MacKay, D., Wong, A. W., & Pearce, E. N. (2019). Iodine Content of the Best-Selling United States Adult and Prenatal Multivitamin Preparations. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association, 29(1), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2018.0386

- 18American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Tobacco, Alcohol, Drugs, and Pregnancy. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://www.acog.org/en/Patient Resources/FAQs/Pregnancy/Tobacco Alcohol Drugs and Pregnancy

- 19CDC. (2017, June 29). Prevent Listeria Infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/risk-groups/pregnant-women.html

- 20Foodsafety.gov, A. S. for P. (2019, April 28). People at Risk: Pregnant Women [Text]. FoodSafety.Gov. https://www.foodsafety.gov/people-at-risk/pregnant-women

- 21Callahan, A. (2018, August 3). What Causes Morning Sickness? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/03/well/what-causes-morning-sickness.html

- 22American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Morning Sickness: Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy. Patient Resources. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://www.acog.org/en/Patient Resources/FAQs/Pregnancy/Morning Sickness Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy

- 23American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea And Vomiting Of Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(1), e15. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002456

- 24Deputy, N. P., Kim, S. Y., Conrey, E. J., & Bullard, K. M. (2018). Prevalence and Changes in Preexisting Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes Among Women Who Had a Live Birth—United States, 2012–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2

- 25CDC. (2019, May 30). Gestational Diabetes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/gestational.html

Image Credits:

- Pregnant woman photo by Omar Lopez on Unsplash (license information)

- Figure 11.1. “Cross-Section of the Placenta” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Figure 11.2. “Components of weight gain in healthy pregnant women with normal BMI before pregnancy.” by Adrian Mercado and Suzanne Phelan, Frontiers for Young Minds is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Table 11.1. “Recommended Weight Gain In Pregnancy” by Alice Callahan is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- “Sunset hike with my wife” photo by Lucas Favre on Unsplash (license information)

- Figure 11.3. “Advice about eating fish” by U.S. FDA and EPA is in the Public Domain

- Figure 11.4. “My Pregnancy Plate” by Christy Naze, RD, CDE, ©Oregon Health & Science University, used with permission.

- Table 11.2. “Recommended Micronutrient intakes during pregnancy” by Alice Callahan is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Chopping cabbage photo by Heather Ford on Unsplash (license information)

- Figure 11.5. “Craniofacial features associated with fetal alcohol syndrome.” by NIH/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism is in the Public Domain

An organ that develops during pregnancy; provides nutrition and respiration, handles waste from the fetus, and produces hormones important to maintaining the pregnancy.