Fact-Checking Online Health and Nutrition Information

In the digital age, we constantly encounter online information, and we have access to far more information than any one person could ever read or comprehend. Some sources are accurate and can be very useful, making us more informed people and citizens. Others are inaccurate and misleading, and engaging with them by reading, clicking, and sharing, can not only be a waste of valuable time but can also increase our chances of spending money on a useless product or even making risky decisions. How do we know which sources of information are worthy of our time and attention, worth sharing with others, or worth informing our own understanding of nutrition and health?

In the case of health information, we’ll encounter plenty of conflicting information about the best diets for health, vaccines, medications, supplements, and wellness products. Social media feeds and search engine results unfortunately don’t prioritize the information that is most accurate or relevant; instead, they often feed us information based on factors like number of clicks or likes, which means that more sensational, attention-grabbing information gets highlighted more often. This demands that we be very discerning about which information sources deserve our attention and which we should ignore. Because we may encounter hundreds of pieces of online information each day, we need to be able to do this efficiently, without taking too much time.

Despite the importance of online fact-checking skills, people often struggle to tell reliable web content from unreliable or false information. In fact, a Stanford experiment found that even Stanford students and professional historians weren’t very good at it.1 Watch the following video to learn more about this study.

VIDEO: “Online Verification Skills – Video 1: Introductory Video” by CTRL-F, YouTube (June 29, 2018), 3:13.

The SIFT Method

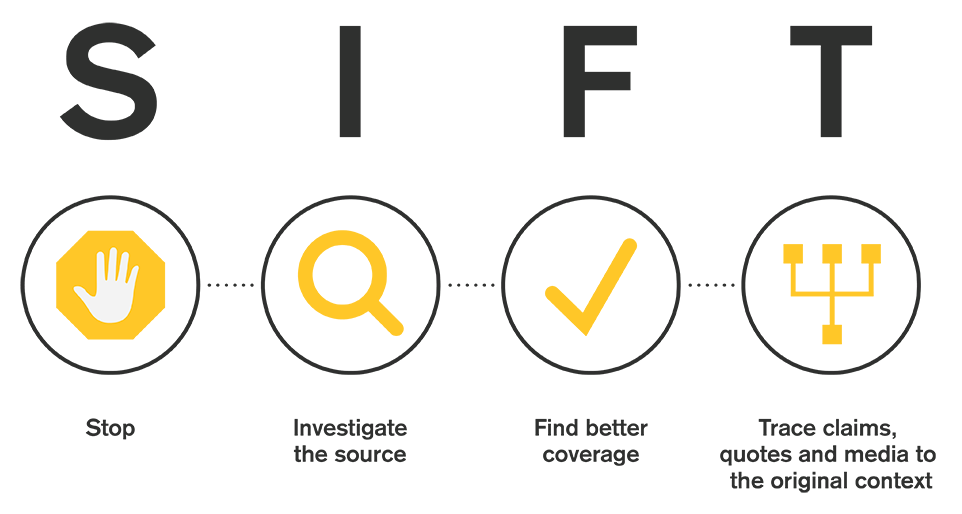

The SIFT method is one approach for quickly fact-checking an online information source. It was developed by Mike Caulfield, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public. The SIFT method includes 4 steps:

- Stop

- Investigate the source

- Find better coverage

- Trace claims to the original context

Fig. 2.7. The Four Moves: Stop, investigate the source, find better coverage, trace the original context.

In this section, which is adapted from Mike Caulfield’s writing, we’ll look at how the SIFT method can help us to evaluate online health and nutrition information.

STOP.

The first move is the simplest. STOP reminds you of two things.

First, when you first hit a page or post and start to read it — STOP. Ask yourself whether you know the website, publication, or other source of information, and if so, if you believe it’s a credible source. If the source is unfamiliar to you or you’re not sure it’s credible, use the other fact-checking moves that follow to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know more about it, and you can verify that it is reliable.

Second, after you begin to use the other moves it can be easy to go down a rabbit hole, going off on tangents only distantly related to the question you were originally trying to answer. If you feel yourself getting overwhelmed in your fact-checking efforts, STOP and take a second to remember your purpose. If you just want to read an interesting story, repost something you think your friends will enjoy, or get a high-level explanation of a concept, it’s probably good enough to find out whether the publication is reputable. If you’re doing deeper research on a topic, such as for a paper you’re writing for a class or to make a health-related decision for yourself or a family member, you’ll want to dig deeper and cross-check multiple reputable sources.

Keep in mind that both sorts of investigations are equally useful. Quick and shallow investigations will form most of what we do on the web. We get quicker with the simple stuff in part so we can spend more time on the stuff that matters to us. But in either case, stopping periodically and reevaluating our reaction or search strategy is key.

INVESTIGATE the source.

The idea here is that you want to know what you’re reading before you read it.

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading an article on why fluoride is added to municipal water supplies, and the author is a dental health researcher at a well-known university, you might engage with this source differently than you would with one authored by an anti-fluoridation activist. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the dental health scientist will always be right, because as we’ve learned, science is an ongoing process in which uncertainty is normal, especially in emerging areas. And it doesn’t mean that the dairy industry can never be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person or organization behind the source will help you decide whether it deserves your attention at all, and if you engage with it, how you interpret the information it provides.

When investigating an online source, effective fact-checkers use a technique called lateral reading. This means that they open a new tab (or many tabs!) in their internet browser to research the source and see what others have said about it. This is usually much more effective than reading “vertically” or staying on the page to see what the source says about itself; if that source is biased or inaccurate, then you’re likely just wasting your time.

VIDEO: “Lateral Reading” by UofL Research Assistance & Instruction, YouTube (June 26, 2020), 3:33.

Watch the following short videos for strategies for investigating the source. Pay particular attention to how navigating off the original site in question can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors.

VIDEO: “Online Verification Skills – Video 2: Investigate the Source” by CTRL-F, YouTube (June 29, 2018), 2:44.

VIDEO: “Online Verification Skills – Video 3: Find the Original Sources” by CTRL-F, YouTube (May 25, 2018), 1:33.

FIND trusted coverage.

What if you realize that you’re looking at a low-quality or biased source of information, or you’re not sure whether it is reliable, but you still want to know if the claim it’s making is true or false? For example, you’re looking at an article that claims that a nutritional supplement will help you run faster, but the same website is also selling the supplement. It’s clearly a biased source of information, and you don’t trust it, but you’re still curious about the supplement.

Your best strategy in this case is to use your lateral reading skills to find a better source altogether, one that includes trusted reporting or analysis on the same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source. Specifically, you want to see if there is a scientific consensus on the benefits and risks of the supplement, or if there is too little evidence to support a consensus—or if there is controversy or disagreement around it.

The point is that you don’t have to stick with that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there. It helps to build a list of go-to trusted sites that you can check for health and nutrition information, (We’ll cover how to search for better sources on the next page.)

Watch the following video for a demonstration of this strategy, and note how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources to provide better coverage.

VIDEO: “Online Verification Skills – Video 4: Look for Trusted Work” by CTRL-F, YouTube (May 25, 2018), 4:10.

TRACE claims, quotes, and media to the original context.

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context, and leaving out the context can dramatically change how a claim, quote, or other media is interpreted.

Maybe you come across a claim about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually supports the claim. Or a celebrity may post a photo highlighting their glowing skin and shiny hairy and claim that these are the results of a scientifically-proven antioxidant-rich diet that they’ve adopted. This claim lacks the full context, like whether they also have a professional hairdresser and makeup artist, or whether the photo was digitally retouched, not to mention information about studies providing evidence on the diet. The missing context in these stories may be intentional—an effort to influence or mislead us—or they may get things wrong by mistake. Either way, searching for context (or just questioning it, in the case of the celebrity photo) can help us determine if the version we saw was accurately presented.

The video below gives an example of one technique that can help you trace media back to the original context: how to check an image.

VIDEO: “Skill – Check the Image” by CTRL-F, YouTube (September 27, 2019), 1:30.

The SIFT method is intended to be a quick way to fact-check claims. But sometimes, when you trace claims back to their original context, you’ll find that the truth is more nuanced than originally presented. That’s OK! Science is full of nuance and uncertainty. The following video gives you some tips for navigating these sticky fact-check situations.

VIDEO: “Skill: Advanced Claim Check” by CTRL-F, YouTube (September 11, 2020), 3:24.

Red Flags of Misinformation

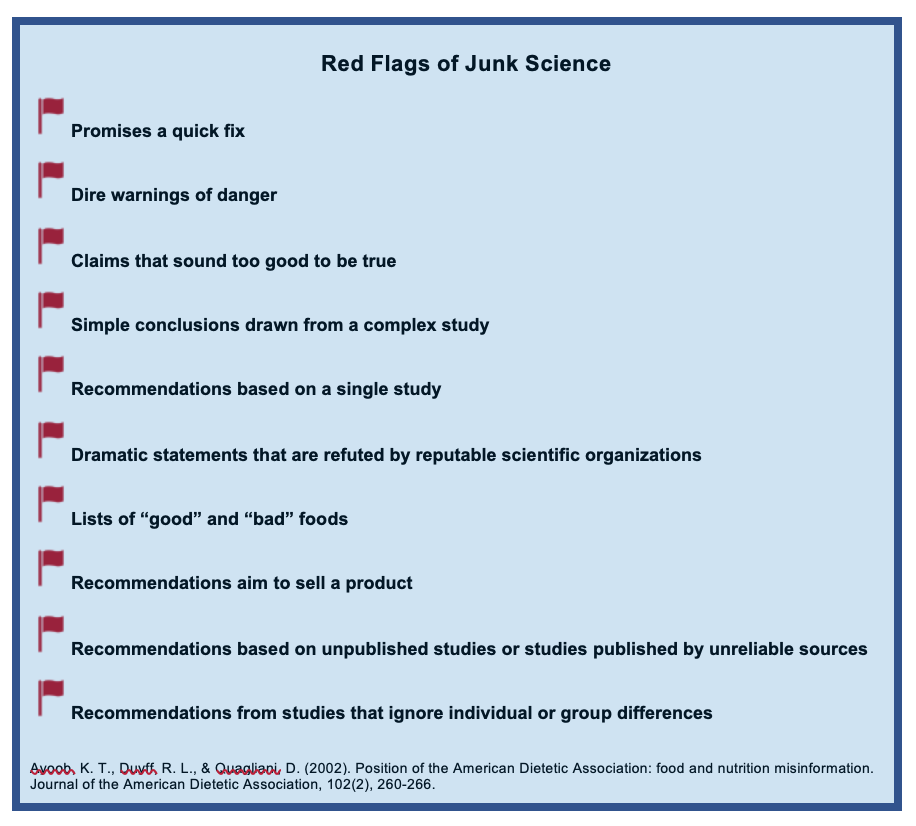

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. That adage holds true for health and nutrition advice. There are several tell-tale signs of junk science—untested or unproven claims or ideas usually meant to push an agenda or promote special interests.2 As you use the steps of the SIFT method, you can also keep an eye out for red flags of junk science. When you see one or more of these red flags, it’s safe to say you should at least take the information with a grain of salt, if not avoid it altogether.

Figure 2.8. The Red Flags of Junk Science were written by the Food and Nutrition Science Alliance, a partnership of professional scientific associations, to help consumers critically evaluate nutrition information.

With so many health claims circulating on social media and other platforms, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and unsure of what to believe. But by practicing the SIFT method and watching for red flags of junk science, you’ll learn to quickly and confidently sort credible information from the noise.

Self-Check Questions:

Attributions:

- Caulfield, M. (2019a). Introducing SIFT. Check, Please! Starter Course. https://www.notion.so, CC BY 4.0.

- Caulfield, M. (2019b, June 19). SIFT (The Four Moves). Hapgood. https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/, CC BY 4.0.

- Butler, W. D., Sargent, A., & Smith, K. (n.d.). Introduction to College Research. Pressbooks. https://oer.pressbooks.pub/collegeresearch/, CC BY 4.0.

References:

- 1Wineburg, S., & McGrew, S. (2019). Lateral Reading and the Nature of Expertise: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information. Teachers College Record, 121(11), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912101102

- 2Ayoob, K.-T., Duyff, R. L., & Quagliani, D. (2002). Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food and Nutrition Misinformation. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(2), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90062-3

Image Credits:

- Fig. 2.7. “SIFT Illustration” by Mike Caulfield is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Figure 2.8. “The Red Flags of Junk Science” by Heather Leonard is licensed under CC BY 4.

A method of evaluating the reliability of online information, consisting of 4 steps: Stop; Investigate the source; Find better coverage; and Trace claims to the original context.

A fact-checking technique that involves checking other sources to research the original source and its claims (rather than trying to assess the original source based on its face value).

Untested or unproven claims or ideas, usually meant to push an agenda, sell a product, or promote special interests.