Risks of Too Little and Too Much Body Fat

As the previous section illustrated, most measures of body composition are imperfect estimates, and they are often not accurate indicators of health. However, in general, carrying too little and too much body fat are both correlated with greater health issues.

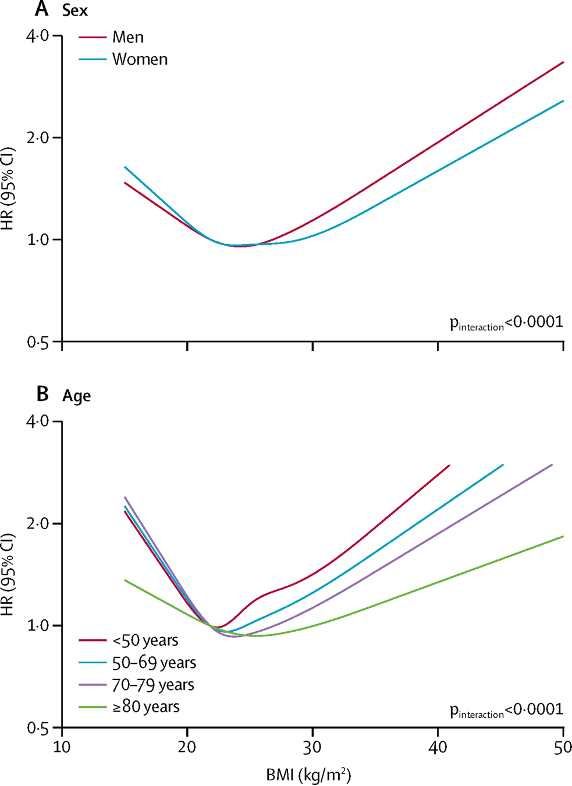

We see this pattern in studies of mortality risk and BMI, which usually report a J-shaped curve indicating a greater risk of dying sooner at low and high BMI. The lowest average mortality risk is usually found somewhere between BMI values of about 20 and 30, corresponding to normal and overweight BMI categories. Which BMI category is correlated to the lowest mortality risk is controversial, and different studies have reached different conclusions depending on the population studied and the statistical methods used. Most studies find the lowest mortality rate in the normal range with little to no increase in mortality in the overweight range for BMI,1-3 and some find that the overweight group has the lowest mortality rate.4-6

As an example, the results of a 2018 study of 3.6 million adults in the UK are shown below.1 You can see that the relationship between BMI and mortality rate varies by biological sex and age group, but the general pattern holds.

Fig. 7.14. The relationship between BMI and mortality risk (higher HR on the y-axis indicates higher risk of dying during the study) forms a J-shaped curve, which can vary depending on factors like sex and age. This example is from Bhaskaran et al. (2018) and illustrates the typical pattern seen in similar studies, although the exact placement of the curve along the BMI scale varies between studies.

What are the specific risks associated with carrying too little or too much body fat? Let’s take a closer look at each of these situations.

Health Risks of Being Underweight

The 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that 1.6 percent of adults and 4.1 percent of children and adolescents in the United States are underweight.7,8 Underweight individuals represent a small portion of Americans, yet the health risks associated with being underweight are an important part of the discussion on nutrition and health. Globally, the World Health Organization estimated that in 2014, approximately 462 million adults were underweight.9

Keep in mind that BMI is used to classify underweight, and just as it’s a crude measure for estimating health risks associated with higher body fat, the same can be true for underweight. Some people are genetically predisposed to be lean, and they may be at their “best weight” even if their BMI classifies them as underweight.

Adipose tissue plays important roles in the body. It is our largest form of energy storage, helping us to survive during periods of low food supply and storing extra energy during periods of abundance. Adipose also provides insulation and padding, and it produces hormones and other signals that regulate metabolism and support immune function. It is critical for reproductive function, including normal secretion of sex and reproductive hormones, pubertal development, pregnancy, and lactation.10

Being underweight has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of several health conditions:11-16

- Osteoporosis and low bone mineral density

- Increased risk of infection, delayed wound healing, and greater post-surgical complications

- Cardiovascular disease, including stroke, heart attack, and coronary heart disease

- Some cancers, plus poorer response to treatment and survival rates after diagnosis

- Irregular menstrual cycles, decreased fertility, and poorer pregnancy outcomes

- Depression in women

- Decreased semen quality in men

- Stunted growth in children

The most common underlying cause of underweight in the U.S. is inadequate nutrition, which may occur because of lack of access to enough food; difficulty eating or digesting food, which is common in older adults; or disordered eating. Note that eating disorders do not always cause underweight and can be present in people of all body sizes. Eating disorders are covered in greater depth on the next page.

Other causes of underweight include wasting diseases like cancer, multiple sclerosis, and tuberculosis. People with wasting diseases are encouraged to seek nutritional counseling, as a healthy diet greatly affects survival and improves responses to disease treatments.

Health Risks of Excess Body Weight

In 2017-2018, it was estimated that 42 percent of adults and 19 percent of children in the United States had obesity.17-18 Globally, the prevalence of obesity was estimated to be 13 percent of adults and 7 percent of children and adolescents in 2016. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overweight and obesity are linked to more deaths worldwide than underweight.19

Carrying too much body fat can affect health through several mechanisms. Fat cells are not lifeless storage tanks—they’re dynamic, metabolically-active tissue that secrete a number of different hormones and hormone-like messengers, causing low-grade inflammation that’s believed to contribute to chronic disease development such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some types of cancer.20 Carrying more body weight can also contribute to joint problems and difficulty with mobility.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity is associated with an increased risk of the following health conditions21:

- High blood pressure and high cholesterol, which are risk factors for heart disease

- Type 2 diabetes

- Breathing problems such as asthma and sleep apnea

- Joint problems such as osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal discomfort

- Gallstones and gallbladder disease

- Stroke

- Many types of cancer

- Depression and anxiety

Children with obesity face many of these same health risks, and they are more likely to have obesity as adults. Obesity in children is also associated with lower self-esteem and facing greater social challenges such as bullying and stigma.21

As we discussed on the previous page, a significant number of people living in larger bodies—who might be classified as overweight or obese based on BMI—are metabolically healthy.22 Health issues may be more common in people carrying more fat, but many other factors are at play, including genetics, the location of body fat (subcutaneous or visceral), diet quality, physical activity, socioeconomic factors, and environmental factors. Most of the studies on obesity and health conditions are observational, and as we covered in Unit 2, observational research can only show correlations, not causation. And with so many overlapping factors involved, it can be difficult to tease apart correlation and causation. For example, a person with a family history and genetic predisposition for diabetes or heart disease might also have a genetic predisposition for higher body weight, so it is difficult to say whether or how much higher body weight contributed to the development of disease.

Likewise, as we’ll discuss later in the unit, factors such as access to healthcare and education, food security, poverty, neighborhood safety, housing stability, stress, and racism can affect both body weight and health. These factors are called social determinants of health and are defined by the CDC as “conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes.” If a person living in a larger body has health problems, we shouldn’t assume that those problems are caused by their weight, as there could be numerous contributing factors.23 In addition, many of the health problems associated with obesity can be mitigated by lifestyle changes such as increased physical activity or improved diet quality, so just as excess weight may not be the sole cause of associated health issues, weight loss is also not the only answer.24

To further add to the complexity of this discussion, studies of the relationship between weight and health rarely account for the effects of weight stigma. As we’ll discuss in more detail below, research has shown that experiencing weight stigma may contribute to both weight gain and poorer health outcomes. In this sense, some of the health problems associated with higher body weight may not be because of the weight itself but because of how others treat people with larger bodies.25,26

All of that said, recent studies have used innovative study designs that incorporate genetic data to better understand the complex relationship between body weight and health conditions. These studies generally find that, although the relationship is neither simple nor the effects universal, excess weight does contribute to increased risk of many health conditions.27-29

Effects of Weight Bias and Stigma

According to the 2020 Joint International Consensus Statement for Ending Stigma of Obesity, “weight stigma refers to social devaluation and denigration of individuals because of their excess body weight, and can lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.” The statement, which was authored by 36 experts from around the world, is a call to action for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and the public to end weight stigma.30 It begins:

“Individuals with obesity face not only increased risk of serious medical complications but also a pervasive, resilient form of social stigma. Often perceived (without evidence) as lazy, gluttonous, lacking will power and self-discipline, individuals with overweight or obesity are vulnerable to stigma and discrimination in the workplace, education, healthcare settings, and society in general. Weight stigma can cause considerable harm to affected individuals, including physical and psychological consequences. The damaging impact of weight stigma, however, extends beyond harm to individuals. The prevailing view that obesity is a choice and that it can be entirely reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more can exert negative influences on public health policies, access to treatments, and research.”

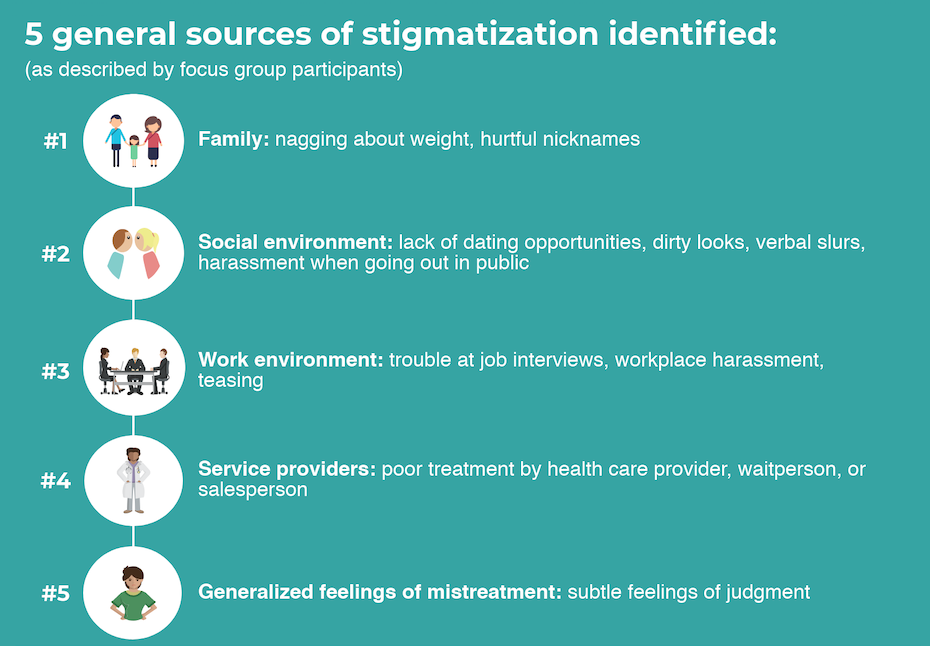

“About 40% of the general population reports that it has experienced some type of weight stigma—whether it be weight-based teasing, unfair treatment, or discrimination,” said Rebecca Puhl, PhD, deputy director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at the University of Connecticut, in Today’s Dietitian.31 Weight stigma can be experienced in nearly every aspect of life, including the workplace, healthcare, social settings, and even within a person’s own family.

Fig. 7.15. Common sources of weight stigmatization identified by individuals who are overweight or obese include families, social environments, work environments, and service providers, as well as generalized feelings of judgment from others. Source: Cossrow, N. H., Jeffery, R. W., & McGuire, M. T. (2001). Understanding weight stigmatization: A focus group study. Journal of nutrition education, 33(4), 208-214.

Experiencing weight stigma has been associated with many negative physical and mental health outcomes30:

- Lower self-esteem and greater levels of depression, anxiety, social isolation, stress, and substance use

- Unhealthy eating and weight control behaviors, such as binge eating

- Exercise avoidance and lower levels of physical activity

- Greater weight gain over time

- Higher levels of inflammatory markers and stress hormones

- Greater long-term cardiometabolic risk and increased mortality

- Lower quality medical care, poorer treatment outcomes, and avoidance of medical care

It is important to note that these effects have been shown to be associated with experiencing weight stigma, above and beyond the consequences of excess body weight. And as noted above, this research points to weight stigma as one of the factors that contributes to poorer health among people with larger bodies.

Combatting weight stigma and discrimination will require change on many levels. Governments can include weight as a category covered in anti-discrimination laws. Anti-bullying efforts at the school level should include policies on harassment and bullying related to weight. Healthcare should include reimbursement for obesity treatment, and weight bias training should be required for healthcare providers. Providers should ensure that their facilities are comfortable and welcoming to people of all sizes, and that they offer evidence-based care and treatment options to all patients, regardless of their size. And education and awareness about weight bias on an individual level will help change negative attitudes toward overweight and obesity.30,32

VIDEO: “Weight of the Nation: Stigma—The Human Cost of Obesity” by HBO Docs, YouTube (May 14, 2012), 18:54. This is video helps increase awareness of weight stigma, humanizing the pain and damage caused by weight bias and discrimination.

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program, “Undernutrition, Overnutrition, and Malnutrition,” CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

- 1Bhaskaran, K., dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., Douglas, I. J., & Smeeth, L. (2018). Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: A population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology, 6(12), 944–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30288-2

- 2Aune, D., Sen, A., Prasad, M., Norat, T., Janszky, I., Tonstad, S., … Vatten, L. J. (2016). BMI and all cause mortality: Systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. The BMJ, 353. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2156

- 3The Global BMI Mortality Collaboration. (2016). Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: Individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet, 388(10046), 776–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1

- 4Flegal K.M., Kit B.K., Orpana H., & Graubard B.I. (2013) Association of All-Cause Mortality With Overweight and Obesity Using Standard Body Mass Index Categories: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA, 309(1):71–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.113905

- 5Romero-Corral, A., Montori, V. M., Somers, V. K., Korinek, J., Thomas, R. J., Allison, T. G., Mookadam, F., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2006). Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet (London, England), 368(9536), 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69251-9

- 6Orpana, H. M., Berthelot, J. M., Kaplan, M. S., Feeny, D. H., McFarland, B., & Ross, N. A. (2010). BMI and mortality: results from a national longitudinal study of Canadian adults. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 18(1), 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.191

- 7Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 16). Prevalence of underweight among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/underweight-adult-17-18/underweight-adult.htm

- 8Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 16). Prevalence of underweight among children and adolescents aged 2–19 years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/underweight-child-17-18/underweight-child.htm

- 9World Health Organization. (n.d.). Fact sheets – malnutrition. World Health Organization. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition

- 10Richard AJ, White U, Elks CM, et al. Adipose Tissue: Physiology to Metabolic Dysfunction. [Updated 2020 Apr 4]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555602/

- 11Golubnitschaja, O., Liskova, A., Koklesova, L., et al. (2021). Caution, “normal” BMI: health risks associated with potentially masked individual underweight-EPMA Position Paper 2021. The EPMA journal, 12(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-021-00251-4

- 12Dobner, J., & Kaser, S. (2018). Body mass index and the risk of infection – from underweight to obesity. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 24(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.013

- 13Park, D., Lee, J. H., & Han, S. (2017). Underweight: another risk factor for cardiovascular disease?: A cross-sectional 2013 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) study of 491,773 individuals in the USA. Medicine, 96(48), e8769. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008769

- 14Underweight. Office on Women’s Health. (2021). Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.womenshealth.gov/healthy-weight/underweight

- 15Han, Z., Mulla, S., Beyene, J., Liao, G., McDonald, S. D., & Knowledge Synthesis Group (2011). Maternal underweight and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analyses. International journal of epidemiology, 40(1), 65–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq195

- 16Guo, D., Xu, M., Zhou, Q., Wu, C., Ju, R., & Dai, J. (2019). Is low body mass index a risk factor for semen quality? A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine, 98(32), e16677. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016677

- 17Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 30). Adult obesity facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

- 18Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April 5). Childhood obesity facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html

- 19World Health Organization. (n.d.). Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 20Harvey, I., Boudreau, A., & Stephens, J. M. (2020). Adipose tissue in health and disease. Open biology, 10(12), 200291. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.200291

- 21Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Consequences of obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/consequences.html

- 22Zembic, A., Eckel, N., Stefan, N., Baudry, J., & Schulze, M. B. (2021). An Empirically Derived Definition of Metabolically Healthy Obesity Based on Risk of Cardiovascular and Total Mortality. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e218505. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8505

- 23Nuttall F. Q. (2015). Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutrition Today, 50(3), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0000000000000092

- 24Koolhaas, C. M., Dhana, K., Schoufour, J. D., Ikram, M. A., Kavousi, M., & Franco, O. H. (2017). Impact of physical activity on the association of overweight and obesity with cardiovascular disease: The Rotterdam Study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 24(9), 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317693952

- 25Puhl, R. M., Himmelstein, M. S., & Pearl, R. L. (2020). Weight stigma as a psychosocial contributor to obesity. The American Psychologist, 75(2), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000538

- 26Tomiyama, A. J., Carr, D., Granberg, E. M., Major, B., Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., & Brewis, A. (2018). How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5

- 27Kim, M. S., Kim, W. J., Khera, A. V., Kim, J. Y., Yon, D. K., Lee, S. W., Shin, J. I., & Won, H. H. (2021). Association between adiposity and cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies. European Heart Journal, 42(34), 3388–3403. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab454

- 28Corbin, L. J., & Timpson, N. J. (2016). Body mass index: Has epidemiology started to break down causal contributions to health and disease?. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 24(8), 1630–1638. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21554

- 29Franks, P. W., & Atabaki-Pasdar, N. (2017). Causal inference in obesity research. Journal of internal medicine, 281(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12577

- 30Rubino, F., Puhl, R. M., Cummings, D. E., Eckel, R. H., Ryan, D. H., Mechanick, J. I., Nadglowski, J., Ramos Salas, X., Schauer, P. R., Twenefour, D., Apovian, C. M., Aronne, L. J., Batterham, R. L., Berthoud, H. R., Boza, C., Busetto, L., Dicker, D., De Groot, M., Eisenberg, D., Flint, S. W., … Dixon, J. B. (2020). Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nature Medicine, 26(4), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0803-x

- 31Dennett, C. The Health Impact of Weight Stigma. Today’s Dietitian Vol. 20, No. 1, P. 24. Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/0118p24.shtml.

- 32Understanding obesity stigma. (2019). Obesity Action Coalition. Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.obesityaction.org/get-educated/public-resources/brochures-guides/understanding-obesity-stigma-brochure/.

Image Credits:

- Fig 7.14. “Relationship Between Body Mass Index (BMI) and Mortality“ is by Bhaskaran et al., published in the Lancet, and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Fig 7.15. “Sources of Stigmatization” by Heather Leonard is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- “Stop Bullying” by jstn-1-7_pe is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Economic and social circumstances, such as poverty and racism, that impact health.

The discriminatory acts targeted towards individuals who live in larger bodies; a result of weight bias.

Negative attitudes, beliefs, assumptions and judgments toward individuals based on their body size.