Solutions for Improving Health

According to a 2019 study, 42 percent of adults in the United States had recently attempted to lose weight, primarily through reduced food consumption and exercise.1 This is not a surprise, given the growing prevalence of obesity and the constant messages of diet culture, which promote thinness as being equivalent to wellness and the latest diet fads as the keys to unlocking good health.

But, as we have learned, the causes of obesity are complex and interwoven into our society, and solutions for improving health will need to be equally far-reaching, going beyond individual efforts at weight loss. On this page, we look at potential solutions to health concerns related to body weight, both at the population and individual level.

Population Level Solutions

Because obesity can affect people over the course of their lifespan and is difficult to reverse, the focus of many of these efforts is on prevention, starting as early as the first years of life. Here, we’ll review some strategies happening in schools, communities, and at state and federal levels.

Focus on Health Equity

Social determinants of health have a strong impact on obesity risk, so prevention efforts understandably target areas such as access to healthy foods and safe and affordable opportunities for physical activity. These are important, but fully addressing them will likely require societies to dig deeper into the root causes of existing disparities, to look at how factors such as poverty, racism, and discrimination affect people’s opportunities for health. This means looking at how communities and governments can work toward health equity, defined as “the fair and just opportunity for all to be as healthy as possible,” requiring removal of obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences.2

Consider low income neighborhoods that lack grocery stores, leaving residents without access to fresh foods and cooking ingredients. Policies and programs that bring groceries into these neighborhoods are important, but they may not do much to improve the nutrition or the food security of residents if they can’t afford to shop there or have no time to cook because they need to work multiple jobs to support their families. Likewise, programs that give children bicycles or teach them about the importance of physical activity may not have an impact if there are no safe places to ride a bike or play in their neighborhood. Looking at this issue through the lens of health equity means tackling even bigger issues of poverty and access to education, resources, and safety. In this sense, policies and programs at community, state, and national levels that seek to improve people’s lives by reducing income inequality and improving access to resources can help to target some of the core causes of obesity in populations.3

An example of community-based interventions that aim to reduce health disparities can be found in the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health across the United States (REACH US) project, launched by the CDC in 2007. REACH US invested in many projects across the U.S., including 14 projects in predominantly Black communities aiming to reduce cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Each community project was unique and depended on local needs and preferences, but all included community coalitions, involving local leaders and residents, and targeted access to healthy food and/or improving physical activity opportunities. Between 2009 and 2012, the prevalence of obesity in REACH US communities dropped by 5 percent, while it increased by 2 percent in nearby comparison communities without a REACH program.4

End Weight Stigma

Weight stigma is a significant barrier to health, particularly for people living in larger bodies. It is harmful to both mental and physical health and counter-productive to the goal of reducing obesity and improving health. The following is the executive summary of the Joint International Consensus Statement for Ending Stigma of Obesity5:

- Weight stigma is reinforced by misconceived ideas about body-weight regulation and lack of awareness of current scientific evidence. Weight stigma is unacceptable in modern societies, as it undermines human rights, social rights, and the health of afflicted individuals.

- Research indicates that weight stigma can cause significant harm to affected individuals. Individuals who experience it suffer from both physical and psychological consequences, and are less likely to seek and receive adequate healthcare.

- Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the prevailing view in society is that obesity is a choice that can be reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more. These assumptions mislead public health policies, confuse messages in popular media, undermine access to evidence-based treatments, and compromise advances in research.

- For the reasons above, weight stigma represents a major obstacle in efforts to effectively prevent and treat obesity and type 2 diabetes. Tackling stigma is not only a matter of human rights and social justice, but also a way to advance prevention and treatment of these diseases.

- Academic institutions, professional organizations, media, public health authorities, and government should encourage education about weight stigma and facilitate a new public narrative of obesity, coherent with modern scientific knowledge.

Support Healthy Dietary Patterns

Interventions that support healthy dietary patterns, especially among people more vulnerable because of food insecurity or poverty, may reduce obesity. Here are some examples:

- Implement and support better nutrition standards for childcare, schools, hospitals, and worksites. The National School Lunch Program in particular provides meals for approximately 30 million children from low-income families each school day, and recent changes in school lunch standards have improved dietary quality for students consuming school lunches.3,6

- Limit or end marketing of processed foods and sugar sweetened beverages, especially ads that disproportionately target children of color.7

- Provide incentives for supermarkets and farmers markets to establish businesses in underserved areas.7

Figure 7.22. Farmers markets can expand healthy food options for neighborhoods and build connections between consumers and local farmers.

- Increase access to food assistance programs and align them with nutrition recommendations. For example, in 2009, the U.S. Department of Agriculture revised the food packages for the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program to better align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The new packages emphasized more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy and decreased the availability of juice. After this change, between 2010 and 2016, there was a decrease in the obesity rate of children in the WIC program.8 Similar progress may be made by increasing access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in order to reduce food insecurity, and providing incentives to use SNAP benefits on foods like fruits and vegetables. Many farmers’ markets now accept SNAP benefits for the purchase of fresh fruit and vegetables.7

- Tax sugary drinks, such as soda and sports drinks, which contribute significant empty calories to the U.S. diet and are associated with childhood obesity. Local taxes on soda and other sugary drinks are often controversial, and soda companies lobby to prevent them from passing. However, research from U.S. cities with soda taxes show that they do work to decrease soda consumption, and one study concluded that a national soda tax may be the most cost-effective obesity prevention measure, estimating that it could prevent more than 500,000 cases of childhood obesity over 10 years.7 In the U.S., soda has only been taxed at the local level, and the tax has been paid by consumers. The United Kingdom has taken a different approach: They started taxing soft drink manufacturers for the sugar content of the products they sell. Between 2015 and 2018, the average sugar content of soda sold in the U.K. dropped by 29 percent.9

- A controversial policy intervention has been the requirement that restaurant menus include calorie information. Beginning in 2018, as part of the Affordable Care Act, chain restaurants in the U.S. with more than 20 locations were required to add calorie information to their menus, and some had already done so voluntarily. Overall, the research on menu labeling has shown it may slightly reduce the calorie count of restaurant purchases, but it doesn’t seem to reduce calories consumed in a sitting, and there’s no evidence that menu labeling affects total calories consumed in the long term, dietary quality, or risk of obesity.10

Fig 7.23. As of 2018, restaurant chains and some other food vendors are required to list calorie counts on their menus. Would these make you pause before ordering?

Support Greater Physical Activity

Physical activity can help maintain energy balance and promote health in many ways, including preventing chronic diseases often associated with higher body weight. The CDC recommends several evidence-based strategies to increase physical activity in communities12,13:

- Activity-friendly routes to everyday destinations – This strategy focuses on creating easier, more appealing, and more accessible opportunities for everyday physical activity within the community. It includes adding sidewalks, bike lanes and paths, hiking trails, and public transit to connect homes, schools, green spaces, parks, worksites, stores, restaurants, and libraries. This infrastructure allows for more physical activity throughout the day.

- Access to places for physical activity – This strategy provides more access (free or reduced-cost) to spaces for physical activity, such as parks, recreation centers, and gyms. It includes workplaces that provide gym facilities and/or time off during the day for physical activity.

- School and youth programs – This includes providing physical activity programs in schools, enhancing physical activity during recess periods, and before- and after-school activities, such as sports and activity clubs.

- Community-wide campaigns – These programs encourage community-wide participation in physical activity through the use of media coverage and promotion, community events, classes, contests, and educational opportunities.

- Social supports – This strategy focuses on building social groups centered on physical activity, such as through walking, cycling, or hiking clubs.

- Individual supports – Worksites, schools, organizations, and churches can offer individuals support in the form of education and counseling to build skills and set activity goals.

- Prompts to encourage physical activity – These include elements such as signs that encourage taking the stairs over using an elevator or choosing walking and biking routes through neighborhoods.

Fig 7.24. There are many ways to increase physical activity, including walking to work, playing with friends, and going for a bike ride.

Individual Level Solutions

While we acknowledge that population level solutions are likely most important for improving the health of communities, we know that individuals may also be concerned about their weight or health. For people who believe that their weight is affecting their health or quality of life, what steps can they take? There is no one-size-fits-all approach. In this section, we’ll discuss lifestyle changes that can improve health (whether or not they result in weight loss), the evidence for weight loss diets, weight loss medications, bariatric surgery, and non-diet approaches.

Biology of Weight Loss and Maintenance

As we discussed earlier in this unit, energy balance determines whether we are gaining, losing, or maintaining body weight. To lose weight, we need to shift into a negative energy balance, so that we are consuming fewer calories than we are burning each day. Most people find that they are able to do this by restricting their calorie or macronutrient intake (i.e., dieting) for a short period of time, perhaps 6 months or a year, and they may lose 5 to 10 percent of their body weight. However, it is very common for people to experience gradual weight regain within a year or two. This fact is what fuels the diet industry; diet companies market their plans based on short-term success stories and frame the longer term reality of weight regain as personal failing or lack of willpower. Even scientific studies of weight loss rarely follow people for more than 12 months, which can lead to reporting of overly optimistic results.14,15

Why is it so difficult to maintain a reduced body weight? Keep in mind that weight, like so many other parts of our physiology, is tightly regulated. Our bodies can make adjustments to both sides of the energy balance equation to help us maintain a steady weight. During periods of negative energy balance, the body signals weight loss as a threat to survival, and these regulatory mechanisms kick in to defend the original weight. Basal metabolic rate drops to conserve energy and protect against starvation. Skeletal muscles also become more efficient, so that they need less energy to fuel their movement. Additionally, after weight loss, there is less physical mass of the body that has to be moved from place to place throughout the day, resulting in fewer calories burned through physical movement and activity, and less metabolically active tissue using calories for fuel throughout the day. These metabolic changes conserve energy, reducing the “energy out” side of the energy balance equation and favoring weight regain.16,17 In individuals maintaining a 10% or greater weight loss, these changes combine to account for an estimated decrease of 300-400 calories in energy expenditure per day beyond what is expected due to the change in body composition alone.18

On the “energy in” side of the equation, neurological and hormonal changes also increase appetite, lower satiety, and increase the brain’s focus on obtaining food. Researchers have estimated that weight loss of about 2 pounds increases appetite by about 95 calories per day.16,17 These biological factors and their influence on weight are discussed further in the video below.

VIDEO: “The Quest to Understand the Biology of Weight Loss,” by HBO Docs, YouTube (May 14, 2012), 22:52 minutes.

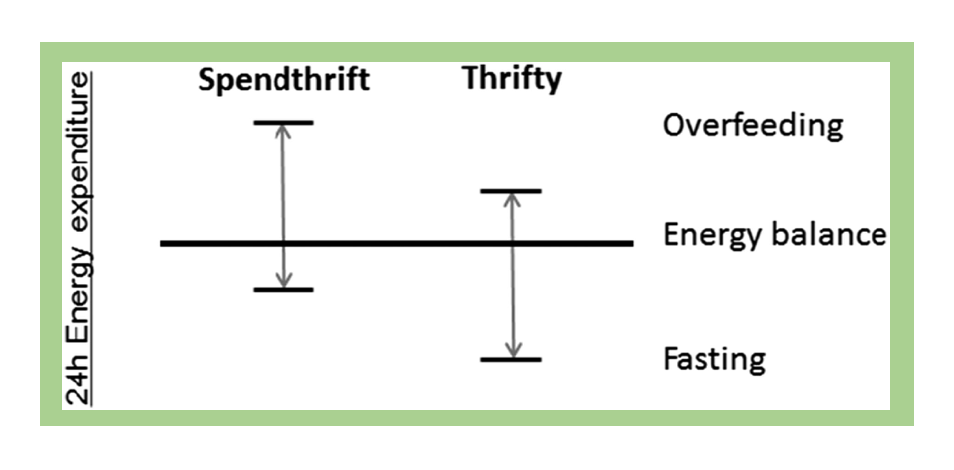

Biological differences in individual metabolism may also impact weight loss and maintenance. Researchers have found that some individuals have a “thrifty” metabolism, meaning that they have a lower metabolic rate and will expend significantly fewer calories when in a fasting or calorie-restricted state, resulting in less weight loss. In contrast, individuals with a “spendthrift” metabolism tend to have a higher metabolic rate in a fasting state, burning more calories and thus yielding bigger weight loss results.19 This research explains why some people may be able to lose weight and maintain weight loss, while others will struggle to do so, even with substantial effort.

Fig. 7.25. Illustration of the concept of spendthrift and thrifty metabolism, characterized by response to overfeeding and fasting.

Setting Goals and Expectations

It’s clear that sustained weight loss is difficult and complex. But weight loss doesn’t need to be the primary goal to improve health. There are many ways to improve your health that aren’t tied to changing your weight or BMI. If you’re at a higher weight and concerned about your weight or health, a good starting point may be thinking of steps you can take to improve your health that are in your immediate control. For example, are you getting enough sleep? What strategies can you take to reduce your stress level? How can you improve your eating habits to better nourish your body? Can you incorporate more enjoyable forms of physical activity into your daily routine? Setting goals around behavior and health rather than a number on the scale improves your likelihood of feeling successful and making sustainable changes. And since many of these daily habits are also thought to affect weight, making positive changes may (but may not) lead to some weight loss. In addition, talk with your doctor about any medications you are using that could cause weight gain.

If weight loss is one of your goals, it’s important to have realistic expectations. The goal of weight loss efforts should be to “prevent, treat, or reverse the complications of obesity and improve the quality of life.”20 Specific goals and approaches will look different for everyone depending on their individual risk factors and lifestyle. Research shows that losing just 5 percent of body weight is associated with significant health benefits such as lower blood pressure and improved blood cholesterol levels, and changing diet or exercise habits typically can reduce body weight by about 5 to 7 percent.20 However, many people set weight loss goals well beyond this mark, leading to disappointment and frustration if they fall short. It may be helpful to set a goal of reaching your “best weight,” defined in the 2020 Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines as “the weight that a person can achieve and maintain while living their healthiest and happiest life.”21

Even more difficult than losing weight is maintaining a reduced weight. Weight regain is common, so at the outset, it’s important to think about how weight loss strategies can be sustained for the long term. Weight control registries from around the world have tracked thousands of people who have successfully lost weight and maintained a reduced weight over time. While these registries include self-selected samples and thus are not representative of all people attempting weight loss, their findings provide some examples of the types of habits associated with maintaining individual weight loss. For example, more than 80 percent of global registry members report consuming breakfast daily, increasing their consumption of vegetables and high fiber foods, eating regular meals, watching their consumption of foods higher in fat and sugar, and keeping healthy foods on hand at home. Physical activity is also an important part of their ongoing efforts; most registry members reported exercising regularly, many for about an hour per day.22

Evidence-Based Dietary Approaches

There are many dietary approaches to weight loss, and research shows that there is no single dietary strategy that is superior to others. Dietary approaches that have been shown to be effective, at least in the short-term, include the Mediterranean diet, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan, vegetarian diet, and a variety of lower-calorie macronutrient distribution diets, such as low-fat and low- carbohydrate approaches.14

While not specifically about weight loss, the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans also offers specific, evidence-based recommendations for dietary habits that provide a good roadmap for healthy eating. These guidelines are aimed at keeping calorie intake in balance with physical activity, which is key for weight management. These recommendations include following a healthy eating pattern that accounts for all foods and beverages within an appropriate calorie level. Unit 1: Tools for Achieving a Healthy Diet includes a more detailed look at these guidelines.

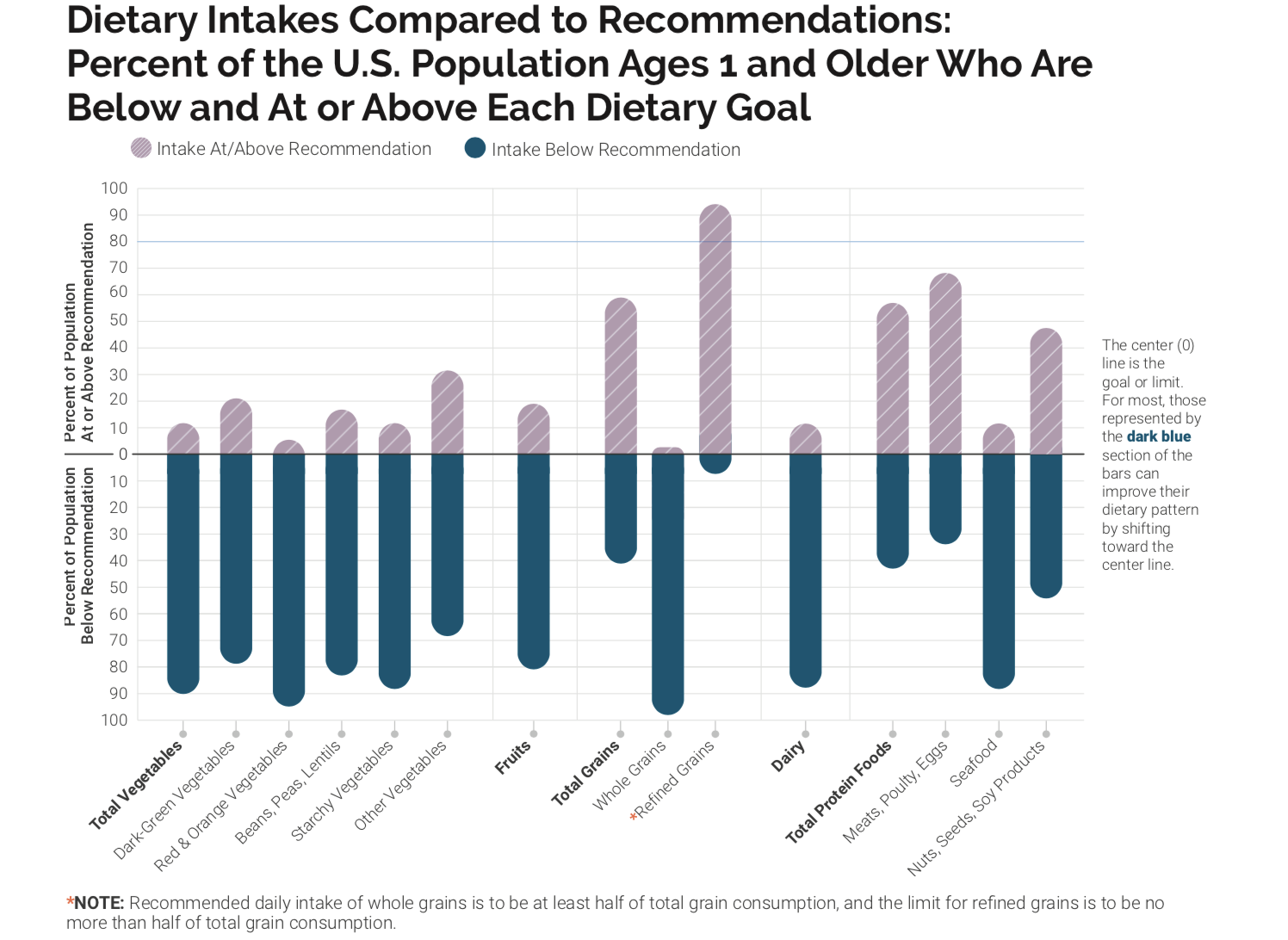

Most Americans do not meet the recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines, indicating room for improvement in dietary quality. Figure 7.26 shows how Americans are falling short of meeting the recommendations for vegetables, fruit, whole grains, dairy, and seafood and consume well over the recommended amount for refined grains. Meanwhile, many Americans also exceed the recommended limits for added sugars, saturated fats, sodium, and alcohol. Shifting towards more nutrient-dense choices, as recommended in the Dietary Guidelines, can help balance caloric intake and better meet nutrient needs for optimal health. In addition, evidence-based guidelines for obesity emphasize the importance of an individualized eating approach that is culturally acceptable, affordable, and prioritizes individual preferences to promote long-term adherence.24

Figure 7.26. This graph indicates the percentage of the U.S. population ages 1 year and older with intakes below the recommendation or above the limit for different food groups and dietary components.

Evidence-Based Physical Activity Recommendations

The other part of the energy balance equation is physical activity. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, issued by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provide evidence-based guidelines for appropriate physical activity levels. These guidelines provide recommendations to Americans aged three and older about how to improve health and reduce chronic disease risk through physical activity. Increased physical activity has been found to lower the risk of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, some forms of cancer, falls and fractures, depression, and early death. Increased physical activity not only reduces disease risk but also improves overall health by increasing cardiovascular and muscular fitness, increasing bone density and strength, improving cognitive function, and assisting in weight loss and weight maintenance.25 In addition, physical activity has been shown to improve mood disorders, body image, and overall health-related quality of life.26 These benefits of physical activity can help counter some of the potential effects of carrying excess weight, and some research suggests that increasing physical activity and fitness levels is more effective than weight loss when it comes to reducing the risk of heart disease and premature death.26 To be most effective, individuals should find activities they enjoy so they can sustain their activity level for lifelong health.27

Key guidelines for physical activity are summarized in Unit 10: Essential Elements and Benefits of Physical Fitness, but a few worth mentioning specific to weight include the following:

- For substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) to 300 minutes (5 hours) per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.

- Engaging in physical activity beyond the equivalent of 300 minutes (5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity per week can result in additional health benefits and may help with weight loss and weight loss maintenance.

- Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities of at least moderate intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week, as these activities provide additional health benefits and promote weight maintenance. Exercises such as push-ups, sit-ups, squats, and lifting weights are all examples of muscle-strengthening activities.

Despite the indisputable benefits of regular physical activity, just 23 percent of Americans met the national physical activity guidelines in 2018, although this number has gradually increased over the last several decades.28 Given the number of Americans that are falling short on both nutrition and physical activity recommendations, both of these areas are of primary interest in improving health in the United States.

Evidence-Based Behavioral Recommendations

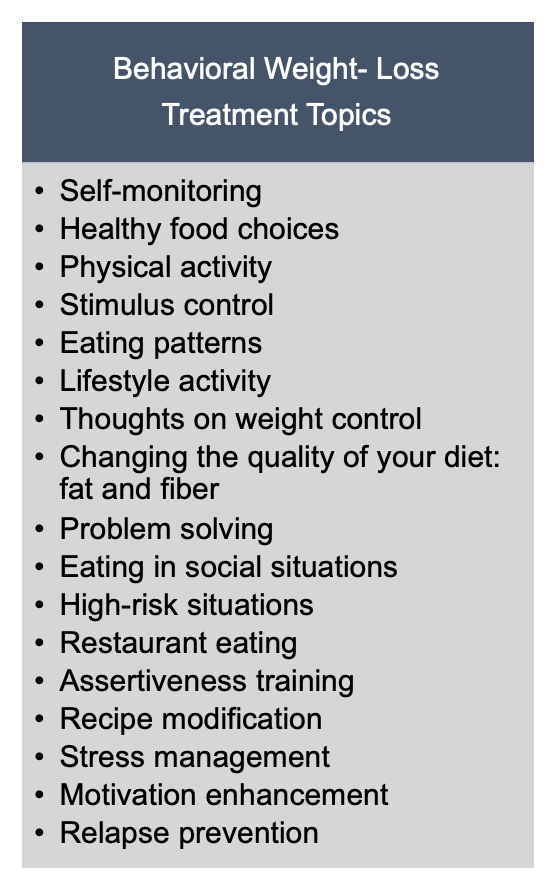

Behavioral weight loss interventions have been described as approaches “used to help individuals develop a set of skills to achieve a healthier weight. It is more than helping people to decide what to change; it is helping them identify how to change.”29 Cornerstones for these interventions typically include self-monitoring through daily recording of food intake and exercise, nutrition education and dietary changes, physical activity goals, and behavior modification.30 Research shows that these types of interventions can result in weight loss and a lower risk for type 2 diabetes, and similar maintenance strategies lead to less weight regained later.31

Behavioral interventions have been shown to help individuals achieve and maintain weight loss of at least 5 percent from baseline weight. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers a 5 percent weight loss to be clinically significant, as this level of weight loss has been shown to improve cardiometabolic risk factors such as blood lipid levels and insulin sensitivity.32,33 The behavioral intervention team often includes primary care clinicians, dietitians, psychologists, behavioral therapists, exercise physiologists, and lifestyle coaches.32 These programs may include a variety of delivery methods, often through group classes of 10-20 participants both in-person and online, and may use print-based or technology-based materials and resources. The interventions usually span one to two years with more frequent contact in the initial months (weekly to bi-monthly), followed by less frequent contact (monthly) in the latter months or maintenance phase.32 A variety of behavioral topics are covered over the course of the program and range from nutrition education and goal-setting, to problem-solving and assertiveness. Relapse prevention is included as participants move into the maintenance phase.31

Fig. 7.27. Common topics included in behavioral interventions for weight loss, adapted from Smith, C. E., & Wing, R. R. (2000). New directions in behavioral weight-loss programs. Diabetes Spectrum, 13(3), 142-148.

One example of a comprehensive behavior intervention is the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). This was a high quality randomized controlled trial that enrolled participants at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes and included an intervention group that made dietary and physical activity changes with the support of frequent meetings with researchers to implement behavioral changes. In the DPP study, participants lost an average of 15 pounds and reduced their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58 percent in the first year. They gradually regained an average of 10 pounds by 10 years later. However, 10 years after the start of the study, intervention participants still had a 34 percent reduced risk in developing type 2 diabetes, indicating significant health benefits of the program.33

The DPP yielded such significant improvements in risk of developing diabetes that it was expanded to a national program available in communities throughout the U.S. To find a DPP intervention program near you, visit the National Diabetes Prevention Program website.

Pharmacotherapy and Bariatric Surgery

When lifestyle changes in diet, exercise, and behavior modification do not produce or sustain meaningful levels of weight loss, the use of medications may be considered to improve weight loss and health outcomes. While continuing with a healthy lifestyle, medications are typically considered for individuals with a BMI over 30, or BMI over 27 with at least one coexisting condition, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, or hypertension.

A newer class of weight loss medications that act similarly to the body’s protein glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and were originally developed as treatments for type 2 diabetes have been shown to be very effective for weight loss and generally have fewer side effects than older medications. As with many drugs used to treat chronic diseases, people generally need to continue using these medications for the long term to avoid weight regain. Over-the-counter weight loss supplements are not monitored by the FDA and are not recommended due to safety concerns.34,35

Surgical interventions may be appropriate for people with a BMI over 40 or BMI over 35 with obesity-related coexisting conditions, so long as they’re motivated to lose weight and behavioral interventions (with or without medication) have not been effective. Potential candidates for surgery should be referred to an experienced bariatric surgeon for consultation and evaluation.20,34

Non-Diet Approaches

In addition to weight management approaches that focus on dietary changes, physical activity programs, and behavioral interventions, there is a growing movement for non-diet approaches for a healthier mentality toward weight, food, and body image. These approaches focus on establishing healthier relationships with food and more body acceptance and positivity regardless of shape and size. They seek to normalize relationships with food, make eating an enjoyable experience focused on well-being rather than dieting, do away with shame or guilt often associated with failed weight loss efforts, and promote respect and inclusivity for all people regardless of weight or size. Mindful eating or intuitive eating are common components of these approaches. These non-diet approaches have been shown to improve quality of life, general well-being, body image, cardiovascular outcomes, physical activity, and eating behaviors regardless of changes in weight status.24

One of these non-diet approaches, the Satter Eating Competence Model, is based on four components: eating attitudes, food acceptance, regulation of food intake and body weight, and management of the eating context. According to Ellyn Satter, a registered dietitian, family therapist, and the founder of the model, competent eaters are “confident, comfortable, and flexible with eating and are matter-of-fact and reliable about getting enough to eat of enjoyable and nourishing food.” This approach enhances “the importance of eating by making it positive, joyful, and intrinsically rewarding.”36 This model emphasizes that by developing a healthier relationship with food, individuals will yield the following benefits:37

- Have better diets

- Feel more positive about food and eating

- Have better overall health

- Have the same or lower BMI

- Sleep better

- Be more active

- Have better physical self-acceptance

- Be more trusting of themselves and others

Health at Every Size (HAES) is another non-diet movement started by the Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH) organization as an alternative to weight-centered health models. HAES aims to decrease our culture’s obsession with body size and weight, decrease weight discrimination and stigma, and instead promote size acceptance and inclusivity.38 Key principles of the HAES approach include:

- Acceptance and respect for the inherent diversity of body shapes and sizes

- Health enhancement through policies and services that promote well-being in all aspects of health, including physical, economic, social, emotional, and spiritual needs

- Respectful care and elimination of weight bias and discrimination through proper education and training

- Eating behaviors driven by hunger, satiety, nutritional needs, and pleasure instead of external regulation by diets and eating plans

- Physical activity through life-enhancing movement for all sizes and abilities

To learn more about non-dieting approaches for a healthy lifestyle, check out the following video.

VIDEO: “Why Dieting Doesn’t Usually Work,” from TED, 12:30 minutes.

It’s clear that obesity is a complex disease that must be managed through a focus on overall health and well-being, not just by changing a number on the scale. Issues around weight bias and stigma must be addressed. Our current health system must improve to support individuals regardless of body shape and size. And current cultural narratives around obesity must change to remove assumptions of weakness or lack of willpower as causes of obesity and eliminate attitudes that cast blame and shame on people living with obesity.24

Self-Check:

References:

- 1Han L, You D, Zeng F, et al. Trends in Self-perceived Weight Status, Weight Loss Attempts, and Weight Loss Strategies Among Adults in the United States, 1999-2006. (2019). JAMA Network Open. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15219

- 2National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A Health Equity Approach to Obesity Efforts: Proceedings of a Workshop in Brief. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25496

- 3Kumanyika, S. K. (2022). Advancing Health Equity Efforts to Reduce Obesity: Changing the Course. Annual Review of Nutrition, 42(1), null. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-092021-050805

- 4Pan, L. (2019). State-Specific Prevalence of Obesity Among Children Aged 2–4 Years Enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children—United States, 2010–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a3

- 5Rubino, F., Puhl, R. M., Cummings, D. E., Eckel, R. H., Ryan, D. H., Mechanick, J. I., Nadglowski, J., Ramos Salas, X., Schauer, P. R., Twenefour, D., Apovian, C. M., Aronne, L. J., Batterham, R. L., Berthoud, H. R., Boza, C., Busetto, L., Dicker, D., De Groot, M., Eisenberg, D., Flint, S. W., … Dixon, J. B. (2020). Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nature Medicine, 26(4), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0803-x

- 6Kinderknecht, K., Harris, C., & Jones-Smith, J. (2020). Association of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act With Dietary Quality Among Children in the US National School Lunch Program. JAMA, 324(4), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9517

- 7Trust for America’s Health. (2021). The State of Obesity: Better Policies for a Healthier America. Retrieved from https://www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021ObesityReport_Fnl.pdf

- 8Pan, L. (2019). State-Specific Prevalence of Obesity Among Children Aged 2–4 Years Enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children—United States, 2010–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a3

- 9Public Health England. (2019). Sugar reduction: Report on progress between 2015 and 2018. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832182/Sugar_reduction__Yr2_progress_report.pdf

- 10Crockett, R. A., King, S. E., Marteau, T. M., Prevost, A. T., Bignardi, G., Roberts, N. W., Stubbs, B., Hollands, G. J., & Jebb, S. A. (2018). Nutritional labeling for healthier food or non‐alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009315.pub2

- 11McGeown, L. (2019). The calorie counter-intuitive effect of restaurant menu calorie labelling. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 816–820. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00183-7

- 12CDC. (2022, May 9). What Works: Strategies to Increase Physical Activity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/activepeoplehealthynation/strategies-to-increase-physical-activity/index.html

- 13Schmid, T. L., Fulton, J. E., McMahon, J. M., Devlin, H. M., Rose, K. M., & Petersen, R. (2021). Delivering Physical Activity Strategies That Work: Active People, Healthy NationSM. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 18(4), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2020-0656

- 14Brown, J., Clarke, C., Stoklossa, C. J., & Sievenpiper, J. (2020). Medical Nutrition Therapy in Obesity Management. In Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Medical Nutrition Therapy in Obesity Management (p. 25). Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/nutrition/

- 15Mann, T., Tomiyama, A. J., Westling, E., Lew, A.-M., Samuels, B., & Chatman, J. (2007). Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. The American Psychologist, 62(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220

- 16Aronne, L. J., Hall, K. D., M. Jakicic, J., Leibel, R. L., Lowe, M. R., Rosenbaum, M., & Klein, S. (2021). Describing the Weight-Reduced State: Physiology, Behavior, and Interventions. Obesity, 29(S1), S9–S24. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23086

- 17Hall, K. D., & Kahan, S. (2018). Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. The Medical Clinics of North America, 102(1), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012

- 18Rosenbaum, M., Kissileff, H. R., Mayer, L. E. S., Hirsch, J., & Leibel, R. L. (2010). Energy Intake in Weight-Reduced Humans. Brain Research, 1350, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.062

- 19Piaggi, P., Vinales, K. L., Basolo, A., Santini, F., & Krakoff, J. (2018). Energy expenditure in the etiology of human obesity: Spendthrift and thrifty metabolic phenotypes and energy-sensing mechanisms. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 41(1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0732-9

- 20Perreault, L., & Apovian, C. (2019). Obesity in adults: Overview of management. UpToDate, Kunins L. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

- 21Obesity Canada and the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons (2020). Clinical Recommendations: Quick Guide; Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. http://obesitycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CPG-Quick-Guide-English.pdf

- 22Paixão, C., Dias, C. M., Jorge, R., Carraça, E. V., Yannakoulia, M., de Zwaan, M., … & Santos, I. (2020). Successful weight loss maintenance: a systematic review of weight control registries. Obesity Reviews, 21(5), e13003.

- 23Research Findings. The National Weight Control Registry. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from http://www.nwcr.ws/Research/default.htm

- 24Wharton, S., Lau, D. C., Vallis, M., Sharma, A. M., Biertho, L., Campbell-Scherer, D., … & Wicklum, S. (2020). Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ, 192(31), E875-E891.

- 252018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/.

- 26Boulé NG, Prud’homme D. (2020). Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Physical Activity in Obesity Management. Available from: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/physicalactivity. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

- 27Gaesser, G. A., & Angadi, S. S. (2021). Obesity treatment: Weight loss versus increasing fitness and physical activity for reducing health risks. IScience, 24(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102995

- 28FastStats. (2021, June 11). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/exercise.htm

- 29Yanovski, S. (2017, December). The challenge of treating obesity and overweight: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board. Roundtable on Obesity Solutions, Washington (DC). Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK475856/.

- 30Smith, C. E., & Wing, R. R. (2000). New directions in behavioral weight-loss programs. Diabetes Spectrum, 13(3), 142-148. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from http://journal.diabetes.org/diabetesspectrum/00v13n3/pg142.htm.

- 31Curry, S. J., Krist, A. H., Owens, D. K., Barry, M. J., Caughey, A. B., Davidson, K. W., … & Kubik, M. (2018). Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama, 320(11), 1163-1171.

- 32Donnelly, J. E., Blair, S. N., Jakicic, J. M., Manore, M. M., Rankin, J. W., & Smith, B. K. (2009). Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(2), 459-471.

- 33Knowler, W. C., Fowler, S. E., Hamman, R. F., Christophi, C. A., Hoffman, H. J., Brenneman, A. T., … & Nathan, D. M. (2009). 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet (London, England), 374(9702), 1677-1686.

- 34Jensen, M. D., Ryan, D. H., Apovian, C. M., Ard, J. D., Comuzzie, A. G., Donato, K. A., … & Loria, C. M. (2014). 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63(25 Part B), 2985-3023.

- 35Perreault, L. (2022). Obesity in adults: Drug therapy—UpToDate. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/obesity-in-adults-drug-therapy

- 36Satter, E. (2007). Eating competence: Nutrition education with the Satter eating competence model. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 39(5), S189-S194. Retrieved November 12, 2019, from

https://www.jneb.org/article/S1499-4046(07)00467-8/abstract. - 37The Satter Eating Competence Model. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from

https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org/satter-eating-competence-model/. - 38The Health at Every Size Approach. Association for Size Diversity and Health. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from https://www.sizediversityandhealth.org/content.asp?id=152.

Image credits

- “Individuals with Obesity” by Obesity Canada is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

- “Grocery shopping photo” is from the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity

- Fig 7.22. Farmers markets. “group of people standing near vegetables” by Megan Markham is in the Public Domain, CC0; “Veggies at Corvallis Farmers Market” by Friends of Family Farmers is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

- “Grocery shopping” by UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity

- Figure 7.23. Menu labeling. “Ballpark Calorie Counting” by Kevin Harber is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Fig 7.24. Increasing physical activity. “Early bird” by Jorge Vasconez is in the Public Domain, CC0; “boy running to the future” by Rafaela Biazi is in the Public Domain, CC0; “people riding bicycles inside bicycle lane beside skyscraper” by Steinar Engeland is in the Public Domain, CC0

- Figure 7.25. Thrifty vs spendthrift genes. Fig. 1. Reinhardt, M., Thearle, M. S., Ibrahim, M., Hohenadel, M. G., Bogardus, C., Krakoff, J., & Votruba, S. B. (2015). A human thrifty phenotype associated with less weight loss during caloric restriction. Diabetes, 64(8), 2859-2867.

- Figure 7.26. “Dietary Intakes Compared to Recommendations” from Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, Figure 1-6 is in the Public Domain

- Figure 7.27. “Behavioral Weight-Loss Treatment Topics” by Heather Leonard is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- “Women Eating” by Obesity Canada is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.

The fair and just opportunity for all to be as healthy as possible.

The discriminatory acts targeted towards individuals who live in larger bodies; a result of weight bias.

Interventions that help individuals develop skills that support healthy lifestyle and body weight.

Approaches that focus on establishing a healthy relationship with food and more body acceptance and positivity regardless of shape and size (e.g: Satter Eating Competence Model, Health at Every Size).

A model developed by Ellyn Satter; focuses on eating attitudes, food acceptance, regulation of food intake and body weight, and management of the eating context.

An approach that aims to decrease our culture’s obsession with body size and weight, decrease weight discrimination and stigma, and instead promote size acceptance and inclusivity.