3.2 Education as a Social Problem

The stories that open this chapter illustrate core issues in education. Sociologists define education as a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. On one hand, the institution is essential. In modern societies, people need the ability to read, write, and think in order to succeed in their societies. On the other hand, not everyone can attain their educational goals.

As we remember from Chapter 1, a social problem is “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world (Leon-Guerrero 2018:4). In this case, because not everyone has access to the education that they need to succeed, we experience negative consequences for individuals, families, and even global communities.

The story of modern education is a story of a significant social shift. As the video in figure 3.1 noted, most people in the world can read and write, something that wasn’t true even a hundred years ago. Although men and boys historically have had more chances to go to school than women and girls, the gender gap in education is closing in the United States and around the world (Roser and Ortiz-Espinosa 2022). Recently, evidence shows that young women are more likely to attend and complete college in the United States than men (Pew Research 2021). These positive results in creating equal access to education don’t tell the whole story, though.

Like every social problem, our social identities and social locations discussed in Chapter 1, play a significant role in the kind of education that is available to us. Social identities and social locations also influence how much school we can finish. When sociologists study education, they find that race, gender, geographical location, socioeconomic status, and all the combinations of these locations have a role in predicting a particular group’s likelihood of succeeding in school. Introductory textbooks commonly focus on race and gender as important predictors of educational success, and they are.

In this section, though, we will focus on the dimensions of diversity that students like you are most interested in understanding—education for d/Deaf, neurodiverse, LGBTQIA+, and Indigenous students. However, if you’d like to learn more about how race and gender affect education, you may be interested in this chapter: An Overview of Education in the United States.

3.2.1 d/Deaf and Black: Intersectional Justice

When sociologists examine the social problems of education, they look at who is defining the problem or claim. We examine the evidence that supports the claims. We evaluate what activists and community members suggest can be done about it. We review law and policy changes to understand their consequences. Finally, we explore how changes might feed subsequent social action.

When we examine educational access and outcomes for d/Deaf students in general and for Black and d/Deaf students in general, we see conflicting claims, different outcomes, and unexpected consequences of law and policy changes. This section explores the experiences of being d/Deaf and being d/Deaf and Black to highlight how inequality is intersectional and why intersectional justice is crucial to attain equity.

Figure 3.3 Being a Deaf Student in a Mainstream School [YouTube Video]. Please watch the first 5 minutes of this video. What experiences does this student have that are the same or different than yours?

As we begin our exploration, you may have noticed that we are using d/Deaf as a general term. This unexpected spelling highlights the first conflict in this area. The more common usage of deaf refers to the medical condition of being physically unable to hear. This traditional definition reflects the perspective of doctors and other medical professionals who define deafness as a medical disability, needing intervention, treatment and special support to enable deaf people to function in a hearing world.

When the word Deaf is capitalized, on the other hand, it refers to a culturally unique group of people. According to Dr. Lissa D. Stapleton, a Deaf Studies professor, “The upper case D in the word Deaf refers to individuals who connect to Deaf cultural practices, the centrality of American Sign Language (ASL), and the history of the community” (Ramirez-Stapleton 2015:569). In this idea of Deafness, Deaf communities have their own language, culture, and practices that are different from hearing cultures but just as valuable. We use d/Deaf in this book to acknowledge the complexity of deafness and Deafness and to discuss both a physical condition and a social location.

Figure 3.4 A family signing using American Sign Language

You may be d/Deaf or know people who are d/Deaf. In that case, you can draw upon your own experiences. The video that opens this section documents one student’s experience. The related picture in figure 3.4 shows people using American Sign Language.

Dr. Stapleton and her collegues explore why college graduation rates for d/Deaf women of color are particularly low. As of 2017, Only 13.7% of d/Deaf Black women get a bachelors degree. In comparison, 26.5% of Black hearing women graduate college. (Garberoglio et al 2019) You may remember from earlier chapters that many social problems are intersectional. People experience them differently based on their various social locations. In this case, Dr. Stapleton looks at how gender, race, and d/Deafness intersect in order to understand the unique experiences of these students. She explains that part of the difficulty for these students is related to being able to be d/Deaf, female and people of color. She shares one story about herself and an Asian d/Deaf student:

I have had several one-on-one interactions with Amy over her two years at the institution. She struggled with shifting identities between her life at home and school. At home, her family treated her like a hearing person; she spoke her ethnic language, participated in all her ethnic cultural practices, and used hearing aids. When she came to school, she only signed and did not interact with other Asian students, as most of the d/Deaf* students on campus were White. She did not feel hearing, Asian, or d/Deaf enough to fit into the residential or campus community. She struggled. Afraid, because of cultural taboos,to tell her parents that she needed counseling and was unable to find a counselor to meet her communication needs (simultaneously signing and speaking), she started to shut down.

The lack of congruency and peace she felt affected her schoolwork, her friendship circles, and now her ability to stay at school because her behavior had become unpredictable and distant.

These stories highlight the experiences of a d/Deaf female Asian student. In some situations being d/Deaf is the most important part of identity. In others, race is a shared experience, either of power or of discrimination. In this story, we begin to see how inequalities in social location set the stage for social problems in education.

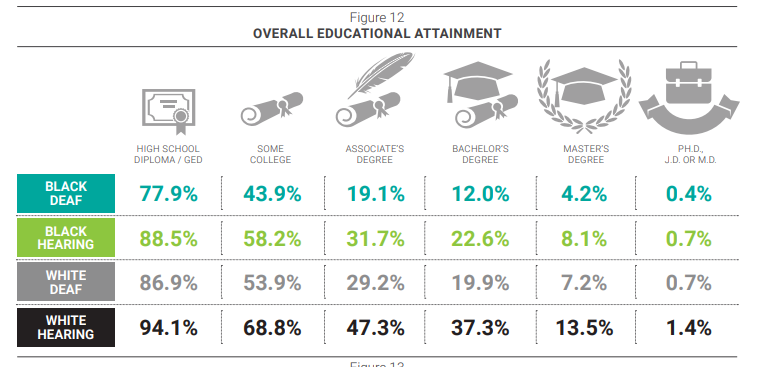

Beyond these stories, though, do we see unequal outcomes in education for d/Deaf students? Let’s look at a small slice of the quantitative data. The table in figure 3.5 addresses the overall educational attainment for Black Deaf, Black Hearing, White Deaf and White Hearing students.

Figure 3.5 Overall Educational Attainment for Black d/Deaf, Black Hearing, White d/Deaf and White Hearing Students, Figure 3.5 Image Description

We notice that hearing people have higher educational attainments than d/Deaf people with the exception of the PhD, JD, or MD levels, in which Black hearing and White d/Deaf people comprise only .7 percent of each population attained that level of education. Black d/Deaf people had the lowest level of educational achievement of any category.

3.2.1.1 Audism and Racism

One factor in explaining the suffering in these students’ stories, and the different outcomes of d/Deaf students is audism. Audism is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). Students who are d/Deaf experience discrimination because others assume that hearing people are superior, and design education with hearing people in mind.

In the words of one student:

Society assumes and exerts superiority over their capabilities of hearings. In Deaf schools, deaf youths are [likely] to experience being discriminated against based on their deafness because the culture is too deep-rooted with the belief that deaf people can do what hearing people do, only that they can’t hear.

…In mainstream schools, I know this because I experienced this more than often. Sometimes I have teachers or interpreters who think I need some assistance with what to say. They think they know our needs. Sometimes we will have someone jump in to “help” us communicate. It is very embarrassing when speaking to a hearing student, especially if we are attracted to them and always have interpreters jump in act like we need their help to talk.

Hearing people misunderstood our facial, body and gesture expressions and avoided us; even told us to “dial down.” (SOC 204 student 2021)

A second factor in the experience is racism. Racism starts with a belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly a belief that White people are superior to Black, Brown or Indigenous people. We’ll dive deeper into race and racism in Chapter 6, but as we saw in the stories of the d/Deaf students, people who are d/Deaf can experience prejudice based on the constellation of their social locations.

3.2.2 Inequality In Education: What’s with All the -isms?

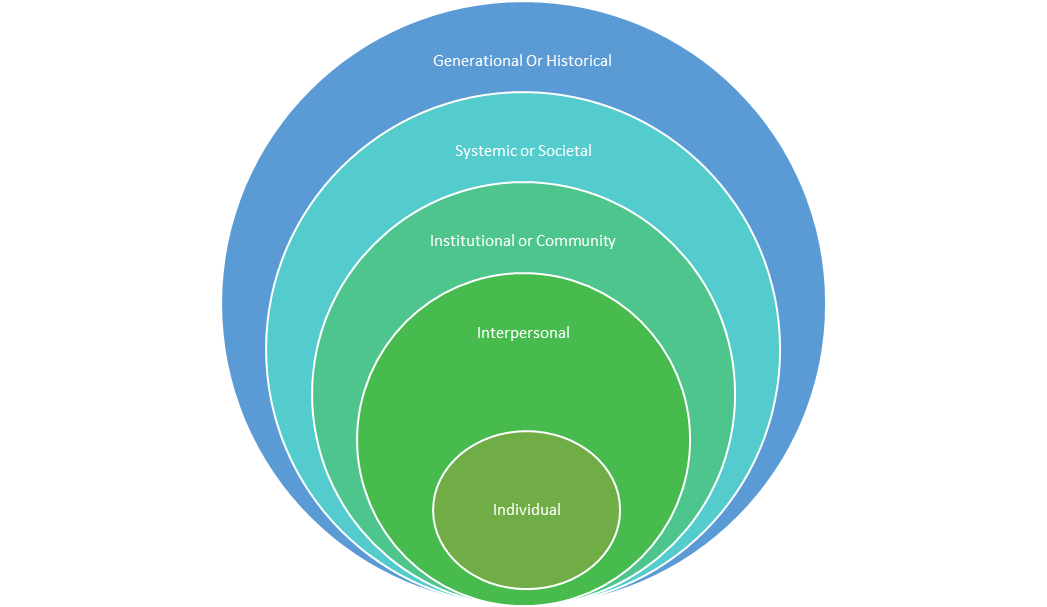

|

Figure 3.6 Social ecology of interdependence: the individual and the interpersonal Audism, as defined earlier, is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). This language and this experience are one example of a class of beliefs that asserts that one group is superior to another. Racism may start with a belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly a belief that White people are superior to Black, Brown, or Indigenous people. Sexism starts with a personal belief that men are superior to women or nonbinary people. Ableism starts with a belief that people whose bodies work as expected are better than people who may not be able to see, hear, walk, or have other challenges. Homophobic doesn’t quite fit the pattern, becase it means fear of queer people, but it points to the flawed belief that straight people are better than queer people. What other words do you know that fit this pattern? Collectively, these beliefs are known as prejudice. More specifically, prejudice is a belief that people of another group are inferior or bad. While humans appear to be wired to notice difference as a survival trait, assigning value or worth to the difference is a problem. Often we have these feelings or beliefs without ever noticing them. When I was considering what to write, the first story that came to mind was, “Imagine that you are White woman, walking alone in the dark on a deserted city street. You might already be afraid. Now, imagine that a Black man turns the corner and is walking toward you. You might feel more afraid.” I am ashamed that this is my first idea, particularly because I know that most of the time women who are raped are raped by someone they know, most often a partner or ex-partner. And yet, the pattern of belief around White and safe remains in my brain. Many of us are unaware of these false beliefs. Researchers at Harvard have developed a set of tests that help people see their own patterns of belief. This test is called the Implicit Bias Test. Implicit means hidden or unspoken. Bias is another word for prejudice. The researchers compare categories of people—women and men, gay and straight, various religions, arab/muslim and other categories. If you’d like to check your own bias, feel free to take a test or two at Project Implicit. Because it is a belief or judgment of a person, prejudice happens internally. It is the first circle in figure 3.6. However, belief also drives behavior. Harmful action that arises from the flawed belief can be as small as a microaggression, as we explored in Chapter 1. It can be a racial slur or a sexist joke. It can be as violent as someone beating up a transgender person because they think the person is using the wrong bathroom. It can be bombing a Black church or a mosque or a synagogue. It can be passing laws that make it illegal to educate entire groups of people. All of these behaviors are discrimination, the unequal treatment of an individual or group on the basis of their statuses. Although the impact of the harm done varies, the belief in the unequal values of people results in behaviors (and systems) that reinforce that inequality. Discrimination is second component of audism, racism, sexism, ableism, and the other -isms that people experience. However belief and behavior are not the only two levels where discrimination can occur. Discrimination happens in our neighborhoods, our schools, our governments, and our countries. It is rooted in the unequal practices of the past, and left unchecked, will flourish in our children. We will refer to the other levels of discrimination throughout the book. For now, it is enough to notice: Where do you see prejudice and discrimination happening in your life, and the lives of the people around you? |

3.2.3 Neurodiversity

Figure 3.7 What is Neurodiversity? [YouTube Video]. As you watch the first 5 minutes of this video, consider the experience of this neurodiverse person. How does inequality in education show up for her?

Activists and scholars notice a parallel between the experiences of Deaf people and neurodiverse people. Deaf people assert that Deaf people form a cultural group. Deafness is not a disability but a normal human variation. Neurodiversity activists use a similar argument. To learn more, you may want to watch the videos in figure 3.7.

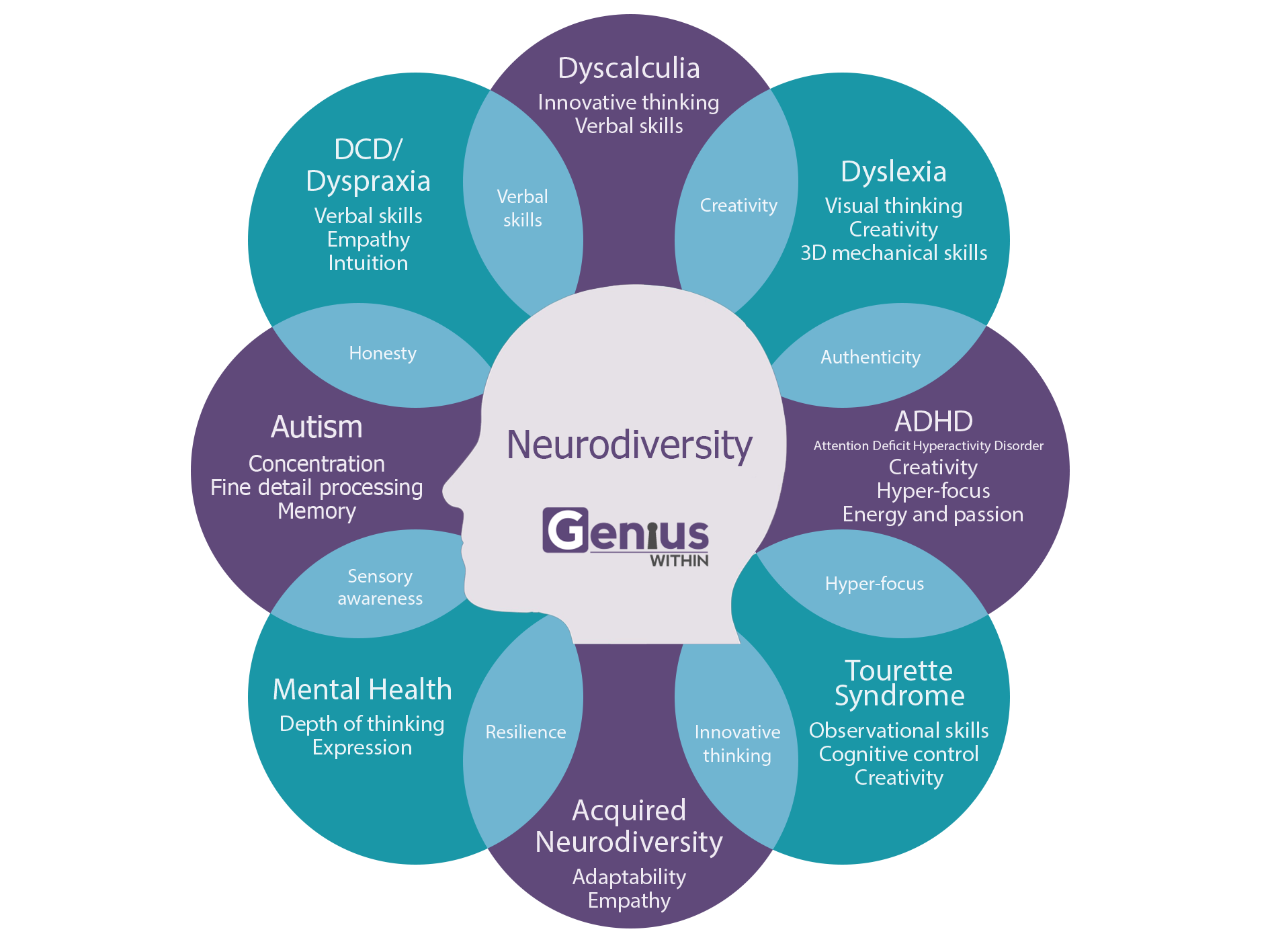

Neurodiversity is a term that means that brain differences are naturally occurring variations in humans. The neurodiversity perspective sees brain differences rather than brain deficits. Instead of viewing differences as disordered or needing to be cured, a neurodiverse perspective sees differences as welcome variants of the human population (Walker 2014; Pollack 2009; Play Spark n.d.).

People whose brains are wired differently than expected are called neurodivergent. Neurodivergent people have significantly better capabilities in some categories, and significantly poorer capabilities in other categories (Doyle 2020).You may hear many labels and diagnosis that make up neurodivergence: ADHD, autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, dyscalculia, learning difference, and many more words.

Researcher David Pollack provides a model of neurodivergence in figure 3.8 which relates several of the labels we listed at the beginning of this section. People experience many different and overlapping learning differences as part of being neurodivergent.

Figure 3.8 Neurodiversity is complicated. (Image created by Genius Within CIC, Source: Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley), Figure 3.8 Image Description

As we move from the individual experience to the social experience, we begin to define the particular social problem. Although estimates differ, Nancy Doyle, a psychologist writing for the British Medical Journal writes that approximately 15 to 20 percent of people worldwide are neurodivergent (Doyle 2020). We see that being neurodivergent is not just the experience of individuals. Rather, it is the shared experience of a group, a needed condition for a social problem.

We also see conflict between how people understand and explain neurodiversity. On one hand, we have a medical model, based on pathology or abnormality (Walker and Raymaker 2021). In this model, differences in reading, calculating, writing or interacting with others is considered a problem, something to be treated or cured.

In the 1990s, adults with these labels began to push back against these categorizations. Their alternate claim was that these conditions should be considered as normal human variants of neurology. Patient-centered care advocate Valerie Billingham coined the phrase, “nothing about me, without me” (1998). She was talking about the need to include the patient at the center of decision-making around patient health and patient treatment choices.

Figure 3.9 Positive experiences of Neurodiversity, Figure 3.9 Image Description

This phrase is used widely today by autism awareness activists, who have expanded the meaning to include the idea that people who are neurodivergent should be the ones describing their own experiences. The letter in figure 3.9 provides one example of this. People with autism are the ones who should make choices about what they need to fully participate in school and in life. They should propose the laws, policies and practices that make their participation possible.

Some experts see neurodiversity itself is a civil rights challenge. They argue that society privileges people who are considered neurotypical. Not only are neurodiverse people stigmatized with a label that implies disease, or symptom or medical problem, social institutions themselves are unequal. They propose that we strive for “neuro-equality (understood to require equal opportunities, treatment and regard for those who are neurologically different)” (Fenton and Khran 2007:1). Likewise, Nick Walker, a queer, transgender, autistic scholar, encourages us to see beyond the medical model. She writes,

The neurodiversity paradigm starts from the understanding that neurodiversity is an axis of human diversity, like ethnic diversity or diversity of gender and sexual orientation, and is subject to the same sorts of social dynamics as those other forms of diversity —including the dynamics of social power inequalities, privilege, and oppression. (Walker 2021)

In this brief explanation, we see the shared experience of a group of people. We see disagreement in how we understand the experience of that group. We see unequal outcomes in school and in life. Activists propose changes, and our government enacts legal and policy changes. This activity leads to new formulations of the problem and requests for action. In short, we see a social problem.

3.2.4 Can You Display A Rainbow Flag at School?

Figure 3.10 Newberg’s ban on pride flags at schools gets national attention [YouTube Video]. Newberg School bans Black Lives Matter and Pride symbols.

In 2021, the school board of the small town of Newberg, Oregon, voted to ban the display of Black Lives Matter and Gay pride symbols at school and found themselves in the national spotlight. The video in figure 3.10 describes the school board’s reasoning and the community’s reaction. This local experience is not unique. In school boards, state legislatures, and national forums students, teachers, parents and community members discuss these questions. For example, on March 28, 2022, Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed the Parental Rights in Education Bill, which prohibits teachers from teaching about sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarden through third grade.

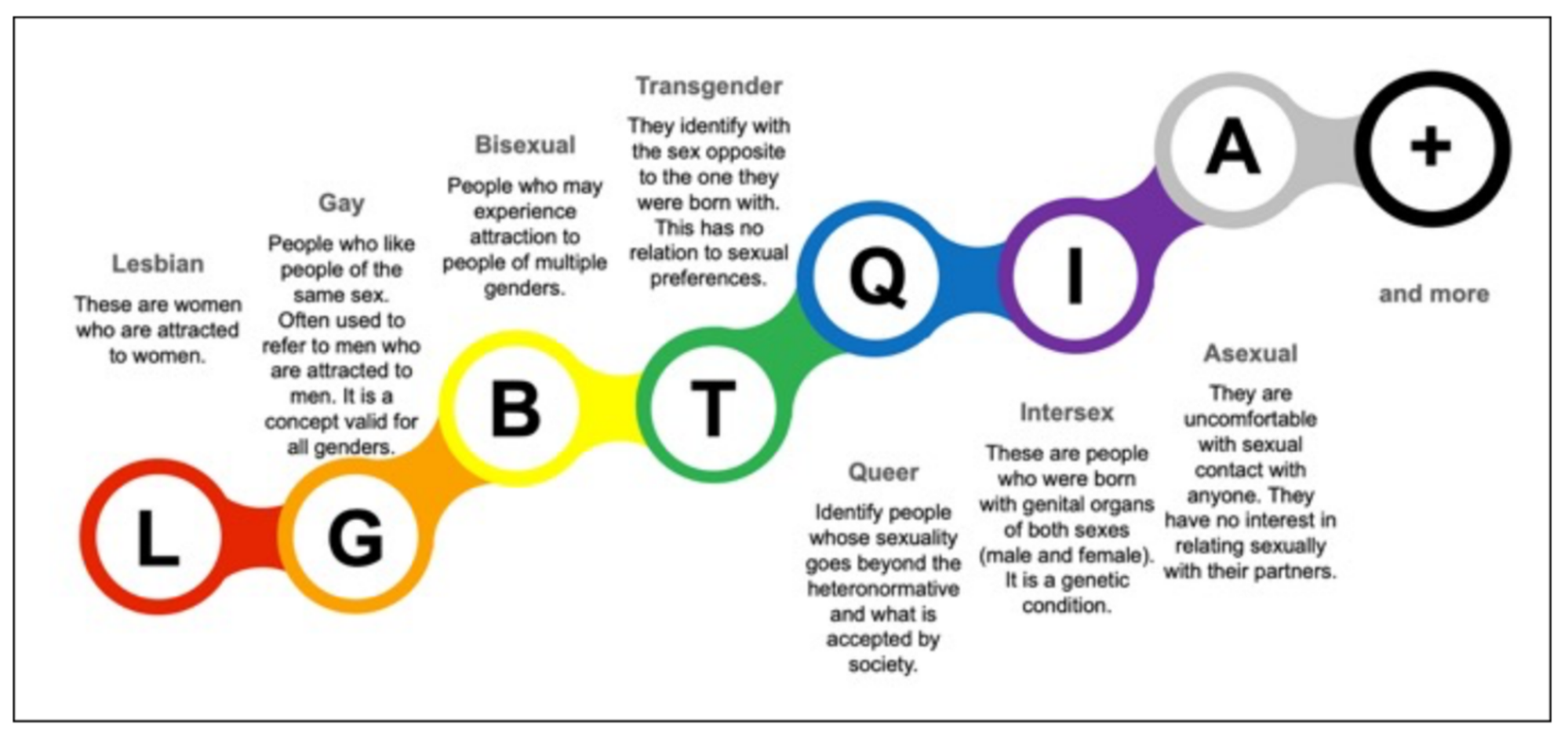

The debate over these decisions reflects a larger social problem for another unique group of students, as shown in figure 3.11. LBGTQIA+ is an acronym which stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex asexual and more. We’ll explore the importance of terminology later in this chapter in “Inequality in Education: Why Do I Say Queer?”

Figure 3.11 People who are queer, Black, and disabled in front of a rainbow flag

The social problem in this case isn’t that the students are LGBTQIA+. It’s that these students face bullying, discrimination, homelessness, and violence because of their gender and sexual identities. When we look at experience in school, most research shows that queer youth are more likely to drop out of high school and less likely to attend college than their straight, cisgender peers (Sansone 2019). When we look at the recent data for Oregon in the 2020 Safe Schools report, LGBTQIA+ youth were twice as likely to be bullied or harassed at school (Heffernan and Gutierez-Schmich 2020).

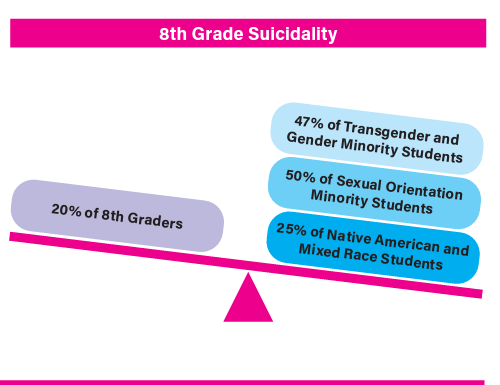

The Safe Schools report takes an intersectional approach by examining gender identity, sexual orientation, and race and ethnicity. The report finds that the more of these marginalized identities a student holds, the more likely they are to be bullied or to be threatened by a weapon at school (Heffernan and Gutierez-Schmich 2020). As the chart in figure 3.12 demonstrates, a person who is transgender or nonbinary, queer, Native American, or mixed race is far more likely to have thought about ending their life or tried to end their life, even as early as eighth grade. The weight of this evidence is compelling. Our LGBTQIA+ students experience bullying, discrimination and violence at school and in the wider world.

Figure 3.12 Safe Schools Report: Eighth grade suicidality by gender, sexual orientation and race, Figure 3.12 Image Description

3.2.5 Why Do I Say Queer?: A Badge of Courage or a Bad Word?

|

For some people queer it is a bad word. For others, it is a source of power. Please take a moment to watch the 3-minute video in figure 3.13 from activist Tyler Ford about the history of the word queer. How do you understand this word? Figure 3.13 Tyler Ford Explains The History Behind the Word “Queer” [YouTube Video] I, Kim Puttman, call myself queer. Queer as in different, but also queer as in challenging dominant ideas about what identity, sexuality, love, relationship and family look like. I also identify as lesbian. I love my wife. Our relationship expands what it means to be “normal” and “healthy.” I embrace this identity as a source of my power, even though it is also a source of my marginalization. I stand with generations of activists before me, chanting “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” In the words of Alex Kapitan, on the Radical Copy Editor blog:

But queer can also be used as a word that conveys hate. When used as an insult, queer is a word that wounds. Using this word as a threat may be grounded in homophobia, the irrational fear of or prejudice against individuals who are or perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual people. More importantly, it maintains heteronormativity, the assumption that heterosexuality is the standard for defining normal sexual behavior and that male–female differences and gender roles are the natural and immutable essentials in normal human relations (APA n.d.). When a bully calls someone queer, they reinforce the idea that straight and cisgender is the only right way to be. So, in this murky terrain, which word do you use? Figure 3.14 offers an illustration that may help:

Figure 3.14 LGBTQIA+ Deconstructed, Figure 3.14 Image Description Although there are many historical reasons that certain names are preferred, it can help to understand that we are looking at continuums of gender and sexual identity. We won’t repeat the dictionary, but you can look for specific definitions of the terms below at the Human Rights Campaign glossary and the Outright International Terminology Blog. The following categories provide an entry point into this discussion about how people describe themselves:

If you want more information on the various continuums of gender and sexual expression check out this great discussion of The GenderBread Person. But, wait, what’s the answer? Can I call someone queer? Maybe, maybe not… My advice is to listen first. If you listen to what people call themselves, you will use the right word, whether queer, lesbian, they, trans, or just me. |

3.2.6 Residential Schools

As we continue our exploration of education and inequality, we see that the institution of education can also support violent and oppressive social change. For this, we look at the history of residential schools in the United States and Canada designed with the explicit intention of disrupting the families and the cultures of Indigenous people.

By establishing boarding schools for Indigenous and First Nations peoples as part of a government-sanctioned attempt to solve the “Indian problem,” colonizers committed genocide, the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. Many indigenous children died in residential schools. The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, released in May 2022. documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021). These deaths are only the start of supporting the claim of genocide. According to Jeffrey Ostler, a historian at the University of Oregon claims of genocide are contested by scholars and activists (like many social problems). Let’s look deeper.

The federal report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 federal boarding schools between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws that required Native American parents to send their children to these boarding schools (Newland 2022:35). Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022:38). Because students were required to learn English and agriculture, and punished, sometimes beaten, if they spoke their Indigenous languages and practiced their own religious and spiritual practices, families and cultures were indeed destroyed.

Figure 3.15 Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior

Deb Haaland, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, describes this history in the following way:

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland, shown in figure 3.15, also recounts the suffering in her own family. She writes, “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian, and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). The 2022 U.S. federal report documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021).

Figure 3.16 Chemawa Indian School

The U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children to attend residential schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition n.d.). Oregon shares this painful history. Historian Eva Guggemos and volunteer historian SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University combed the historical record for the Forest Grove Indian Training School in Forest Grove which became the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (figure 3.16). They found that at least 270 children had died while at these schools. Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases. “The Forest Grove Indian Training School, 1880–1885 [YouTube Video]” tells more of the story.

Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural assimilation, the process by which the members of a subordinate group adopt the aspects of a dominant group. In this case, the colonizers valued their own White European culture and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in figure 3.17 and 3.18 tell the story.

Figure 3.17 A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.”

Figure 3.18 Seven months later — the students pictured are probably the Spokane students who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief.

A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck.

Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse.

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures. (Francis 2019)

The function of education in the case of Native American boarding schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. Education functioned to purposefully disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to education of Indigenous children were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. Jefferson wrote:

To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts. (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21)

By removing people from the land, and children from families, the U.S. government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, using education as one method of enforcement.

3.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Problem

“Education as a Social Problem: d/Deaf Education, Neurodiversity and Rainbow Flags” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.3 “Being Deaf in a Mainstream School” by Rikki Poynter. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.4 ASL family by David Fulmer . License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.5 “Overall Educational Attainment” (p.12) by © National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes Postsecondary Achievement of Black Deaf People in the United States. License: BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 3.6 “Social Ecology of Interdependence: The Individual and the Interpersonal” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.7 “What is neurodiversity?” by The Counseling Channel. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.8 Neurodiversity is complicated © Genius Within CIC / Source: Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 3.9 Photo by walkinred. License: CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Figure 3.10 “Newberg School BLM and Pride are Banned” by KGW News. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.11 Photo by Chona Kasinger, Disabled And Here. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.12 “8th Grade Suicidality by Gender, Sexual Orientation and Race” in Safe Schools Report by Julie Heffernan and Tina Gutierez-Schmich. Used under fair use.

Figure 3.13 “Tyler Ford Explains The History Behind the Word ‘Queer’”. by them. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.14: LGBTQIA+ acronym © 2021 by Harold Tinoco-Giraldo, Eva María Torrecilla Sánchez.and Francisco J. García-Peñalvo License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.15 Deb Haaland by the U.S House Office of Photography is in the Public domain.

Figure 3.16 Chemawa Indian School by Library of Congress is in the Public domain.

Figure 3.17 Caption from A Tragic Collision of Cultures by Mike Francis. Fair Use.

Figure 3.18 Caption from A Tragic Collision of Cultures by Mike Francis. Fair Use.