5.3 Inequality, Intersectionality and Culture

We’ve looked at how the beginnings of the environmental movement can be understood using the social problems process. We also understand that social problems can arise when there is a conflict between values, the ideas that we have about what is right or good. Our values arise from our culture. Let’s pause for a moment and think about what we mean when we use the word “culture.”

In every interaction, we all adhere to various rules, expectations, and standards that are created and maintained in our specific culture. In Chapter 1, we learned that these norms have meanings and expectations. The meanings can be misinterpreted or misunderstood in many ways. When we do not meet those expectations, we may receive some form of disapproval, such as a look or comment informing us that we did something unacceptable. For example, someone trying to connect with you may ask: “What do you think of the weather we’re having?” If you ignored their question or simply walked away instead of responding, that person may look at you oddly or say something else to get your attention.

Consider what would happen if you stopped and informed everyone who asked “What do you think of the weather we’re having?” exactly what you thought and what concerned you about the weather in detail. In U.S. society, you would violate norms of ‘greeting.’ Perhaps if you were in a different situation, such as having coffee with a good friend, that question might warrant a detailed response.

This norm violation is an example of culture. Culture includes:

- shared values (ideals),

- beliefs that strengthen the values,

- norms, and rules that maintain the values,

- language so that the values can be taught,

- symbols that form the language people must learn,

- arts and artifacts,

- and the people’s collective identities and memories.

Sociologically, we examine in which situation and context a certain behavior is expected and in which it is not. People who interact within a shared culture create and enforce these expectations. Sociologists examine these circumstances and search for patterns.

5.3.1 Enculturation and Cultural Universals

Anthropologist Edward Tyler (1871) was one of the earliest social scientists to define culture, stating that it was “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits” that people learn from other members of their group. In other words, culture is both learned as well as taught. Anthropologists call the process of learning culture enculturation. A Western example of enculturation is the belief that we must work to earn the right to live. Children are taught from young ages that we must work jobs until we become elderly to afford our basic necessities, such as food, shelter, water, and acceptance within our communities. This is steadily reinforced throughout adolescence and into adulthood through toys, media, job fairs, career days, and so on.

Culture also includes the institutions we create, the mental maps we perceive to be “reality,” and the power structures that shape our understanding of the world. It is important to note that culture is not static. Rather, it is a dynamic process that is constantly evolving and being shaped, reinforced, and negotiated by members within the cultural group. We learn culture from our parents and other family members, our teachers and religious leaders, the media, and the larger communities and societies we are a part of. Fundamental to the definition of culture is that it is a shared experience that develops in response to being a member of a group.

All cultures have to solve similar problems – how to find enough to eat, how to raise children, how to care for the sick, or memorialize those who have died. Although cultures vary, they also share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies.

One example of a cultural universal is the family unit. Every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions vary. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead.

In the U.S., by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit that consists of parents and their offspring. Other cultural universals include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. However, each culture may view and conduct the ceremonies quite differently.

Anthropologist George Murdock first investigated the existence of cultural universals while studying systems of kinship around the world. Murdock found that cultural universals often revolve around basic human survival, such as finding food, clothing, and shelter, or around shared human experiences, such as birth and death or illness and healing.

Through his research, Murdock identified other universals including language, the concept of personal names, and, interestingly, jokes. Humor seems to be a universal way to release tensions and create a sense of unity among people (Murdock 1949). Sociologists consider humor necessary to human interaction because it helps individuals navigate otherwise tense situations.

5.3.2 The Culture Wheel

As a sociologist exploring a social problem, you might look at the ways in which the cultures of the participants reflect different values, norms, languages, or laws in order to better understand the conflict. To remind ourselves of what these cultural differences can be, we have the culture wheel to help (figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 The culture wheel helps us to understand what is common and different in many cultures. When you consider your own cultural background, how is it the same or different from the dominant culture? Figure 5.5 Image Description

How might you use this culture wheel to explain your own culture to someone else?

Part of why the conflict is so hard to resolve when it comes to the environment is that we see a deep conflict between culture and the related world views.

According to Alan Johnson, a sociologist you met in Chapter 1, a worldview is

The collection of interconnected beliefs, values, attitude, images, stories, and memories out of which a sense of reality is constructed and maintained in a social system and in the minds of individuals who participate in it. (Johnson 2014:180)

Like culture, a worldview helps a person make sense of their world. A worldview can be a perceived reality of how things are due to societal reinforcement. For example, in the dominant worldview in the United States, the concept of race is partially based on the physical characteristics of people, such as skin tone and hair texture.

In the past, it was assumed that you could tell someone’s race just by looking at them. Today, we know that the concept of race is socially constructed and real in its consequences. The beliefs and prejudiced actions of some people are reinforced by the social structures of law and institutional policies.

Sociologically speaking, we know that race as a social construct occurred as a result of the combination of capitalism and colonialism. Initially, the English used “race” as a way to divide English people from Irish people, legitimizing taking Irish land. Once created, “race” as applied to Indigenous, African, and other “non-white” people became a justification for genocide, domination, and colonization. (Johnson 2014)

5.3.3 Colonialism

5.3.3.1 What is Colonialism?Many school children in the United States can tell us that our country began as thirteen colonies. However, this basic understanding is a bit flawed. Immediately before the American Revolution, Great Britain actually had 17 colonies. Thirteen of these colonies eventually revolted. They became the new country, the United States of America. The other colonies, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Prince Edward Island, remained colonies of Great Britain during this war. They became part of the confederation of Canada in 1867. (Canada became fully independent of Great Britain in 1982) The school child version of thirteen colonies also simplifies a much more complicated reality. The bigger version of this history includes a deep history of violence, genocide, and colonialism across the planet. But what do we mean when we say colonialism? Colonialism is the domination of a people or area by a foreign state or nation : the practice of extending and maintaining a nation’s political and economic control over another people or area. When we say that Great Britain had 17 North American colonies, we mean that Great Britain made the laws, provided the leaders, bought firs, wood, and minerals, and imposed taxes. The colonizers who lived there were citizens of Great Britain, but had no rights to vote. The indigenous people had even less. 5.3.3.2 Who Were the Colonists and When Did Colonialism Occur?As we see in this video first introduced in Chapter 2, Spain, Portugal, France, England, China, and Russia were and continue to be major colonizing powers. In the video below, starting about video minute 16, we can see the expansion of Spain and Portugal into Central and South America, starting in the 1500s. By video minute 16:30, France, England, and the Netherlands establish colonies in North America. By about video minute 17:17, we see Great Britain establishing colonies in Australia and Canada, and much of Africa “owned” by Spain, Portugal, and Great Britain. It is only after World War II and the rise of nationalism in the 1950s and 1960s that the power of colonialism wanes. The map at video minute 18:09 shows mostly independent states worldwide. Figure 5.6: The History of the World: Every Year [YouTube Video] 5.3.3.3 Impact of colonizationToday, some places in the world are still colonies or territories of other states. Puerto Rico is a US territory. The people who live there are US citizens, but they can’t vote in many elections. Similarly, the Falkland Islands, small islands off the coast of Argentina, are legally recognized as territories of the United Kingdom and claimed as part of Argentina at the same time. However, most of the world’s countries govern themselves independently. Why then, is colonialism still important? Learning about colonialism is necessary because we are still feeling the effects of this historical legacy. European world powers established global slavery in this time period. Colonizers killed the people who already lived on the land through disease, war and resettlement. As we discussed in Chapter 3, colonizers used education as a way of destroying family and community. Indigenous communities around the world still feel the effects of this destruction. Similarly, colonization is happening to Indigenous communities right now. Palestine is a modern example of colonization in action, with devastating and violent effects. 5.3.3.4 Colonialism and Climate ChangeIn addition to the decimation of Indigenous populations and the land that they lived on, colonization supported a worldview that contributes to ecological devastation today. In this view, land is to be owned and subjugated, rather than tended and cared for. In the words of authors Laura Dominguez and Colin Luoma (who write using UK English):

Further, colonization supports a worldview that leads its participants to value individual well being above all else. This leads to a lack of action and concern regarding the well being of our neighbors, plants, and animals who surround us. How might you see this worldview at work in many of our social problems? |

5.3.4 Comparison of Indigenous and Western World Views

Although Indigenous peoples worldwide are significantly different from one another, Indigenous people, social scientists, and activists assert that there is an Indigenous worldview. From Chapter 1, we remember that the social construction of language is important. Let’s talk first about who we mean – Indigenous, First Nation, or Indian.

The United Nations describes Indigenous peoples in this way:

Indigenous peoples have in common a historical continuity with a given region prior to colonization and a strong link to their lands. They maintain, at least in part, distinct social, economic and political systems. They have distinct languages, cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems. They are determined to maintain and develop their identity and distinct institutions and they form a non-dominant sector of society. (United Nations)

The United Nations doesn’t define who is indigenous on purpose, asserting that indigenous people have the right to identify themselves for themselves.

In an alternate definition, the Canadian organization Indigenous Foundations defines First Nations as:

a term used to describe Aboriginal peoples of Canada who are ethnically neither Métis nor Inuit. This term came into common usage in the 1970s and ‘80s and generally replaced the term “Indian,” although unlike “Indian,” the term “First Nation” does not have a legal definition. While “First Nations” refers to the ethnicity of First Nations peoples, the singular “First Nation” can refer to a band, a reserve-based community, or a larger tribal grouping and the status Indians who live in them. For example, the Stó:lō Nation (which consists of several bands), or the Tsleil-Waututh Nation. (First Nations Studies Progam, n.d.)

Indigenous Foundations then goes on to describe the term Indian as:

the legal identity of a First Nations person who is registered under the Indian Act. The term “Indian” should be used only when referring to a First Nations person with status under the Indian Act, and only within its legal context. Aside from this specific legal context, the term “Indian” in Canada is considered outdated and may be considered offensive due to its complex and often idiosyncratic colonial use in governing identity through this legislation and a myriad of other distinctions (i.e., “treaty” and “non-treaty,” etc.). In the United States, however, the term “American Indian” and “Native Indian” are both in current and common usage.

You may also hear some First Nations people refer to themselves as “Indians.” While there are many reasons for an individual to self-identify this way, this may be a deliberate act on their part to position and present themselves as someone who is defined by federal legislation. (First Nations Studies Progam, n.d.)

Although Indigeous people throughout the world have very different cultures, their collective worldview is significantly different from the Western worldview. If you’d like, please read this story “What I Learned from Coyote” and this explanation of world view, “As I had shared with Coyote” In them, Jennifer Anaquod, indigenous educator and researcher and member of the Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation in Saskatchewan, describes her world view through story.

We’ve summarized some of the core differences in Indigenous and Western worldviews in the table in Figure 5.7. Each worldview defines relationships to wealth and to land. In the Indigenous view, land is sacred, to be cared for from generation to generation. Wealth is shared. In the Western world view, land is owned or controlled, and the purpose of living is to accumulate wealth.

|

Indigenous Worldview |

Western Worldview |

|

Collectiveness |

Individualism |

|

Wealth is shared |

Accumulate wealth |

|

Natural world more important |

People’s laws are more important |

|

Land is sacred we belong to the land |

Land is a resource, is dangerous, and must be controlled |

|

Silence is valued |

Silence needs to be filled |

|

Generosity |

Scarcity |

|

Binaries do not exist |

Binaries are crucial |

Figure 5.7 Differences between the Indigenous World View and the Western World View

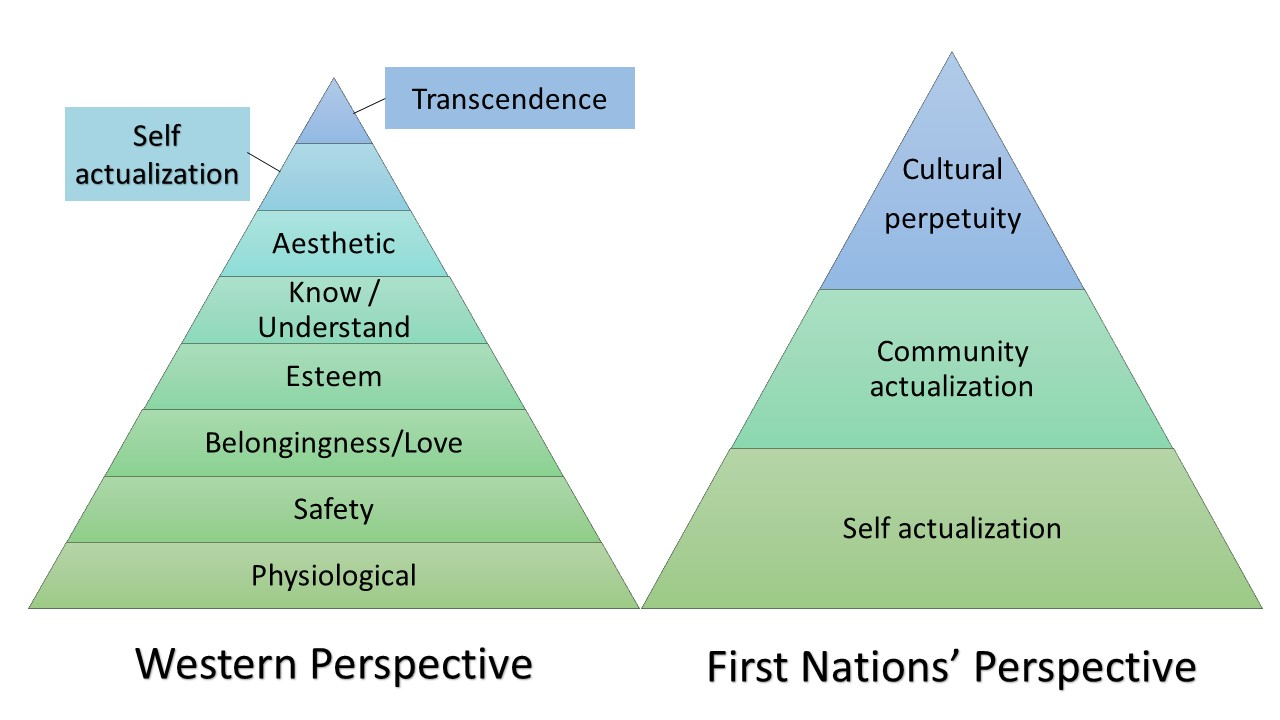

We see a difference in worldview also, when we examine how we understand what people need to thrive and grow. At some point in your education, you may have seen the triangle on the left. In figure 5.8, the triangle (left) shows Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Figure 5.8 Comparison between Maslow’s Hierarchy and First Nations Perspective. Figure 5.8 Image Description

It includes the emotional need for affection and loving connections to others once basic physiological and biological needs are met. In contrast, figure 5.7 (right) shows theories created by multiple indigenous groups, and best documented by the Blackfoot Nation in North America, that emphasize the self-actualization of not just the individual, but of the community as the most primary of needs.

An example that illustrates the differences between the dominant Western perspective today versus Indigenous or First Nations perspective is our current economic system, better known as capitalism, an economic system based on market competition and the pursuit of profit, in which the means of production or capital are privately owned by individuals or corporations.

What this definition lacks, however, is that capitalism is a result of colonization and is perpetuated by a difference in cultural value. Capitalism is an economic system that requires endless consumption and use of resources, which is not sustainable on a finite planet. This underlying reasoning is relevant in many values of our culture, which results in the internalization of these values. For instance, internalized capitalism can be seen in how we consume resources, what we see as valuable forms of work, and what we determine to be basic living standards.

Figure 5.9 Carvers Owen James and Herb Sheakley, and tribal member George Dalton, Jr. hoist the Kaagwaantaan house post. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a rich source of wisdom.

Indigenous or First Nation’s economic systems, in general, have not relied on exponential growth and consumption to live a healthy lifestyle. Many journals from early colonists describe the Americas as places with lush and ample resources. This is because Indigenous peoples had consistently managed and stewarded the land using techniques that had been perfected throughout generations. This knowledge today is called Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or TEK.

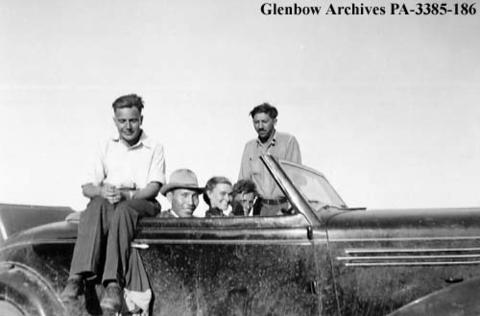

Figure 5.10 This photograph shows Abraham Maslow visiting Blackfoot (Siksika) reserve in Canada where he and his team conducted anthropological research. The people from left to right are Fritz Lenel (visiting German friend), Howard McMaster (Blackfoot interpreter), Jane Richardson (later Hanks), Lucien Hanks, and Abraham Maslow. Taken while Hanks and Maslow were conducting anthropological research on the reserve. How might the study findings be different if the indigenouse people were conducting the research themselves?

In 1938 Maslow spent time with the people of the Blackfoot Nation in Canada prior to releasing his Hierarchy of Needs theory (figure 5.8). Historians think that he based the teepee-like structure on the Blackfoot ideas but westernized the focus to be on the individual rather than on the community (Bray 2019).

If we look more closely at the representation of Blackfoot ideas, it can be seen that the well-being of the individual, the family, and the community are based on connectedness, the closeness that we experience with family and friends, and the prosocial extension that we provide to others in our communities and in the world. In addition, this model focuses on time; the top of the teepee is cultural perpetuity and it symbolizes a community’s culture lasting forever.

5.3.5 Licenses and Attributions for Inequality, Intersectionality and Culture

“Inequality Intersectionality and Culture” by Kimberly Puttman and Avery Temple, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

5.3 Values and 5.3.1 Enculturation is adapted from “Chapter 3 Introduction” and “3.1 What is Culture” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax Sociology 3e is licensed underCC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to the social problem of climate change. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

Figure 5.5 “The Culture Wheel” (c)AndreaGrace J. Fonte Weaver. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission

Figure 5.6 “The History of the World Every Year” © Ollie Bye. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.7 Differences between the Indigenous World View and the Western World View by Avery Temple. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.8 Maslow’s Hierarchy and First Nations Hierarchy Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens by Elizabeth B. Pearce; Wesley Sharp; and Nyssa Cronin is licensed under a CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted.[g]

Figure 5. 9 Carvers Owen James and Herb Sheakley, and tribal member George Dalton, Jr. hoist the Kaagwaantaan house post from National Park Service is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.10 “Anthropologists and interpreter on the Blackfoot (Siksika) reserve, Alberta” by Jane and Lucien Hanks, Archives Society of Alberta is in the Public Domain.

Colonialism Pedagogical Element by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.