1.3 Constructing a Social Problem

Sociologists argue that social problems are socially constructed. In order to explain why some issues become relevant to particular communities, sociologists propose a process, or sequence of steps, that an issue undergoes before it becomes a social problem. These steps may include requests for action and subsequent responses. Although other sociologists propose different numbers and definitions of the steps, sociologist Joel Best proposes a useful six-step process.

1.3.1 The Social Problems Process

In order to explain why social problems come to our attention sometimes and not others, sociologists look for patterns across many social problems. As early as 1940, Richard Fuller and Richard Myers proposed a model for social problem creation, action, and resolution. They called the model a natural history of a social problem. It may seem odd to you at first to hear social problems described in terms of natural history.

More simply, Fuller and Myers are asking us to be excellent observers, looking at the social world in the same way a biologist would study nature. A biologist would observe, gather evidence and give explanations of patterns that she sees. Sociologists who study social problems also observe and organize details into steps or models. They use those models to explain social phenomena, or predict what might happen next. In this book, we describe this approach as the social problems process.

Recently, sociologist Joel Best proposes a more detailed framework for the social problems process. In it, he includes steps for identifying and debating what a social problem is. He considers modern technology by describing how social media can rally people to a cause or promote government programs. He also expands our understanding of how the government takes action with social problems and helps us think about what happens next. This model is helpful because it allows us to explore what is common in social problems, and perhaps more importantly, what is effective in trying to solve them. The following sections walk through the model step by step.

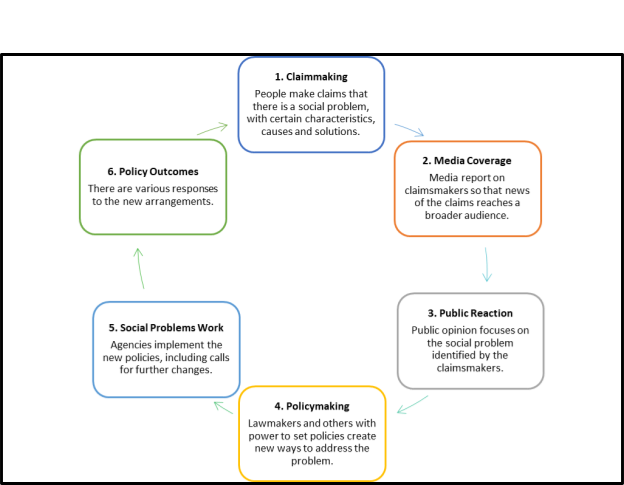

Figure 1.12: Best’s model of claimsmaking, adapted by Kim Puttman from Best 2021 Figure 1.12 Image Description

1.3.1.1 Step One: Claimsmaking

In this step, people and groups identify an issue and try to convince others to take it seriously. In this step, the problem is called a claim, or “an argument that a particular troubling condition needs to be addressed” (Best 2021:15). In this stage, people who may or may not agree that a problem exists agree on what to do about it or discuss who should take action. In Best’s classic example, civil rights activists made claims that racial segregation and lack of access to the rights of citizens was unacceptable. They held sit-ins, boycotts, marches, and demonstrations to assert their claim. The people conducting these actions are claimsmakers, the “people who seek to convince others that there is a troubling condition about which something needs to be done” (Best 2021:15).

1.3.1.2 Step Two: Media Coverage

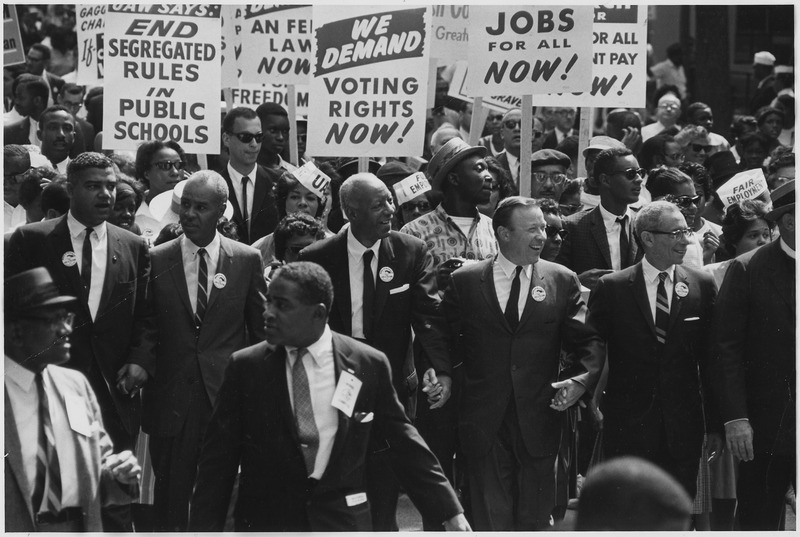

Figure 1.13 Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. Black and White leaders protested together Figure 1.13 Image Description

In the second step, claimsmakers work to find other people and groups who agree with them on the causes, impacts, and desired outcomes of the particular issue at hand. Civil rights activists, as pictured in figure 1.13, used newspapers, radio, and television to build an audience sympathetic to the needed civil rights changes. Dr. King used his gift for impassioned speaking to encourage media coverage and gain wide agreement about how and why civil rights should change.

1.3.1.3 Step Three: Public Reaction

In this step, individuals, groups, and organizations begin to align to a particular explanation of the problem and request a change in policy or law. Most of the time, at this step it is the power of social movements that create the changes in policy or law. For example, the marches for civil rights in the United States lead to Congress passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1.3.1.4 Step Four: Policy Making

In the policy making step, governments create new laws and institutions that result in creating new policies to implement a response to a social problem. Response to the social problem requires institutions with power to take action to make change. With civil rights, race-based segregation became illegal at the federal level.

1.3.1.5 Step Five: Social Problems Work

Once a new policy is put into place institutions must act to implement the change. For the civil rights movement, this work included integrating schools, which we will talk about more in Chapter 3. It included registering Black and Brown people to vote. It included ending the segregation of public spaces.

1.3.1.6 Step Six: Policy Outcomes

In this step, claimsmakers examine the outcomes of the policies and actions taken to respond to the social problem. Often, the outcome of this step is making the claim stronger and requesting more action. The civil rights movement became a training ground for the women’s rights movement and the protests against the war in Vietnam. People who learned to organize, march, and lead non-violent resistance in the civil rights movement used these skills to advocate for women’s rights, ending the war in Vietnam, and beginning to expand recognition of the LGBTQIA+ community. As a step in the social problems, the disparate outcomes are publically shared. We continue the cycle of social problem creation and resolution, moving toward a new—and potentially transformative—normal.

1.3.2 “Stories Are Data with Soul”: A Critique of the Social Problems Process

The social problems process is a useful framework for understanding social problems, but it has four major limitations:

- Social problems are objectively real, not just socially constructed.

- Organizations and people can take effective action to change social problems, not just governments.

- Our stories illuminate our understanding of social problems effectively.

- Explanations of power, not just resources, are critical in counting the cost of resistance to social problems.

First, even though constructionists argue that social problems only occur if people notice them, suffering in any person’s life can occur whether anyone is paying attention to it. In the constructivist view, a social problem only exists if people agree that it does. Other sociologists, though, point out that we share common values. Violating these common values is a social problem.

Sociologist Rudolfo Álvarez (2001) asserts that there are seven universal values, including the values of life over death, health over sickness, and cooperation over competition Other universal values include that people should be able to learn, make their own choices, live where they want, and say what they think. While we construct our social reality, we do so against the background of these core values. So, whether anyone notices that a child dies of malnutrition, a man beats his wife, a soldier shoots a civilian, or a bully taunts a queer teenager, these actions cause suffering. In this sense, social problems exist whether or not they ever make headlines.

Second, changes in government policy aren’t the only ways that social problems can be addressed. Changing the structural inequalities that are the foundations of many social problems often requires a change in law. However, other effective strategies for resolving social problems also exist. For example, when responding to issues of alcohol addiction, the grassroots movement which led to the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous has changed the social conversation about what it means to be an alcoholic. While it took Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) to modify laws related to drinking and driving, the creation of a self-help community shifted how we think about drug misuse. In another example, local community members were the first (and most lasting) group of people to gather supplies for Echo Mountain Fire Survivors and to clear fire survivor property. While government agencies play a vital role, government intervention isn’t the only measure by which a social problem can be impacted.

A third criticism of the social problems process is that it downplays the importance of individuals’ stories. In the social problems process, Best argues that case studies, a technical word for stories, are not useful in explaining social problems (2018). Other sociologists disagree. For example, professor and teacher Brené Brown calls herself a researcher/storyteller. She writes, “Stories are data with a soul” (Brown 2022). She asks people about their lives, exploring what makes them resilient or brave. By looking for common threads in people’s stories, she can propose explanations about what is true. Stories allow us to make sense of things from the perspective of the person who tells them. We tell stories to find out who we are, to teach our children about the world, and to imagine possible futures. For this book and this class, I encourage you to think about your own story. How does it help you make sense of your life?

Fourth, in using the language of claimsmaking and resources, the social problems process downplays the power of people who are wealthy in determining which problems get attention. Sociologist Rudolfo Álvarez points this out, writing:

How are social problems discovered by various groups in society . . . ? The answer, of course, is that a social problem comes into existence when a sufficiently powerful population becomes collectively aware of a condition it considers to be threatening to its well being and, consequently, sets out to alter those conditions so as to reduce the perceived threat. (Álvarez 2001)

This definition is unusual because it focuses on the use of power as a determining force in constructing a social problem. Often sociologists focus on people without power coming together to protest as a method of resolving a social problem. This criticism points out that people with money can get the attention of lawmakers and the media much more easily than others. With this focus, for example, homeowners who are annoyed with the tents and shopping carts of houseless people in their neighborhoods would be the ones to complain and organize, not the houseless people themselves.

Figure 1.14: Argentine singer Mercedes Sosa and American activist Holly Near sing Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone” The song tells the story of women protesters in Chile who dance, telling the story of their husbands, children and fathers who have been murdered in Chile.

Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone

They’re dancing with the missing

They’re dancing with the dead

They dance with the invisible ones

Their anguish is unsaid

They’re dancing with their fathers

They’re dancing with their sons

They’re dancing with their husbands

They dance alone

They dance alone

It’s the only form of protest they’re allowed

Ellas danzan con los desaparecidos

Ellas danzan con los muertos

Ellas danzan con amores invisibles

Ellas danzan con silenciosa angustia

Danzan con sus padres

Danzan con sus hijos

Danzan con sus esposos

Ellas danzan solas

Danzan solas

The song, Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone, is a contemporary protest song written by Sting and sung here by Mercedes Sosa and Holly Near. (figure 1.14). Feel free to listen. The lyrics written in section 1.3.2.1 refer to the women, men, and children who were killed while protesting against the dictator Agusto Pinochet who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990. The song also laments the deaths of protesters in other Latin American countries, people who went missing because they dared to speak against the government. If you’d like to learn more about efforts to find these people in Chile, please explore this news article about current efforts.

This song highlights another limitation of the social problems process we explored in the previous section. On the surface, the social problems process implies that all claimsmakers have equal access to media. You might assume that everyone can influence policymakers or respond to policy outcomes. However, this is not the case. Best, among others, adds the component of access to resources to help explain the tenacity of some social movements and the related changes they may cause. Best writes, “a society’s members are not equal. Some have more money than others, or more power, more status, more education, more social contacts, and so on. These are resources that people can draw upon in the social problem process” (Best 2021:24, emphasis added).

Focusing on resources as a component of why some collective actions work and some fail makes sense. However, it also hides a deeper reality. Marginalized people are more likely to die sooner than people with power. For example, Black, Brown, and Indigenous people get COVID-19 more often and are likely to die sooner than White people (CDC 2022). LGBTQIA+ teenagers are more likely to be homeless than straight teenagers (youth.gov 2022). People who are disabled are at higher risk to die sooner than non-disabled people, even when you take into account any complicating medical conditions. (Majer et al. 2011). As these examples show, lives are risky for people in the margins. When sociologists use the bland word ‘resources’, they mask this danger.

Figure 1.15 Activist Dolores Huerta, Nov. 10, 2015 speaking for Black Lives Matter, Immigrant Justice and the Fight for $15

In addition to life itself being riskier, organizing, protesting, and agitating carry greater risk to people who are oppressed. Activist and author Dolores Huerta, pictured in figure 1.15, reminds us that “the power is in your body” (quoted in Boyle 2017), and that all of us can protest. However, state sanctioned or community violence may cost activists their lives, their health, their jobs, or their families. Bringing “resources” to social action can exact extreme costs from already marginalized people.

1.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Constructing a Social Problem

1.3.3.1 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.13. “Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.” by Rowland Scherman, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.15. “Dolores Huerta” by Susan Ruggles is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

1.3.3.2 All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.14. “They Dance Alone/Ellas Danzan Solas” by Holly Near is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Partial lyrics are included under fair use.

1.3.3.3 Open Content, Original

“Constructing a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.12. “Best’s Model of Claimsmaking” designed by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Image Description for Figure 1.12:

The six steps of claimsmaking defined and organized in a circle: 1. Claimsmaking: People make claims that there is a social problem, with certain characteristics, causes, and solutions. 2) Media Coverage: Media…report on claimsmakers so that news of the claims reaches a broader audience. 3) Public Reaction: Public opinion focuses on the social problem identified by the claimsmakers. 4) Policymaking: Lawmakers and others with the power to set policies to create new ways to address the problem. 5) Social Problems Work: Agencies implement the new policies, including calls for further changes.

[Return to Figure 1.12]

Image Description for Figure 1.13:

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.

Leaders marching from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. In the front row, from left are: Whitney M. Young, Jr., Executive Director of the National Urban League; Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, American Federation of Labor (AFL), and a former vice president of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO); Walter P. Reuther, President, United Auto Workers Union; and Arnold Aronson, Secretary of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. Aug. 28, 1963.