9.3 Social Location and Mental Health

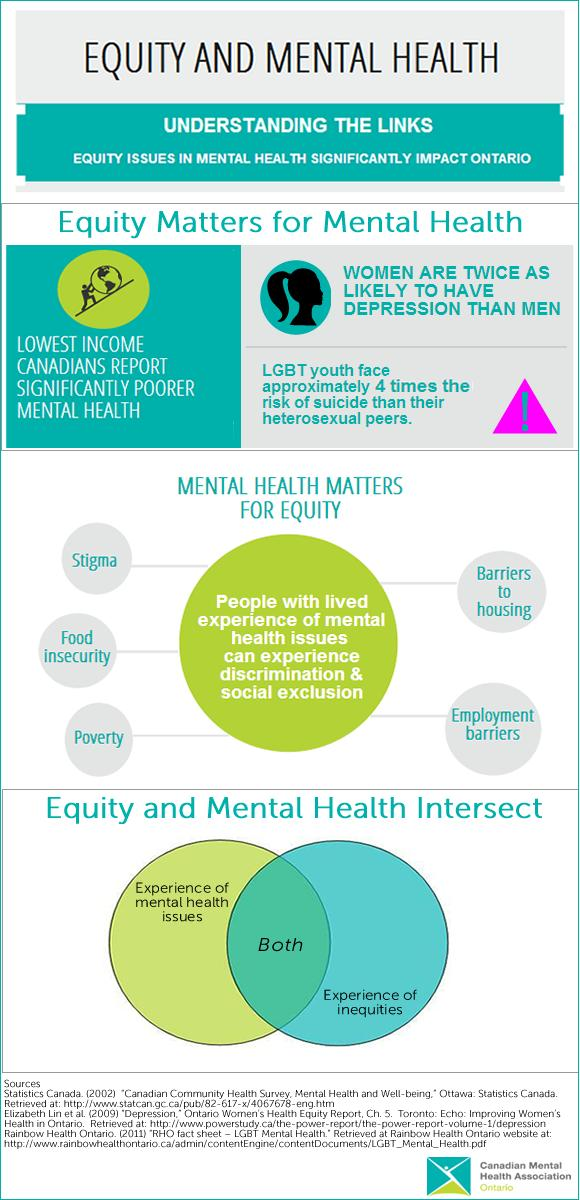

Figure 9.9 Equity Matters to Mental Health: Equity and Mental Health impact each other

The infographic in figure 9.9, Equity Matters to Mental Health, highlights the intersectional nature of social location and mental health. In the related report, the Canadian Mental Health Association-Ontario describes the relationship between equity, mental health, and intersectionality:

- Equity matters for mental health. Due to decreased access to the social determinants of health, inequities negatively impact on the mental health of Ontarians. Marginalized groups are more likely to experience poor mental health and in some cases, mental health conditions. In addition, marginalized groups also have decreased access to the social determinants of health that are essential to recovery and positive mental health.

- Mental health matters for equity. Poor mental health and mental health conditions have a negative impact on equity. And while mental health is a key resource for accessing the social determinants of health, historical and ongoing stigma has resulted in discrimination and social exclusion of people with lived experience of mental health issues or conditions (PWLE).

- Equity and mental health intersect. People often experience both mental health issues and additional inequities (such as poverty, racialization, or homophobia) simultaneously. Intersectionality creates unique experiences of inequity and mental health that poses added challenges at the individual, community and health systems level. (Canadian Mental Health Association, n.d.)

Mental health status itself can influence your ability to stay in school, hold a job, or raise a family. And the reverse is also true—if you are struggling to put food on the table, keep your kids stable, or stay safe in your neighborhood, you are more likely to have poor mental health.

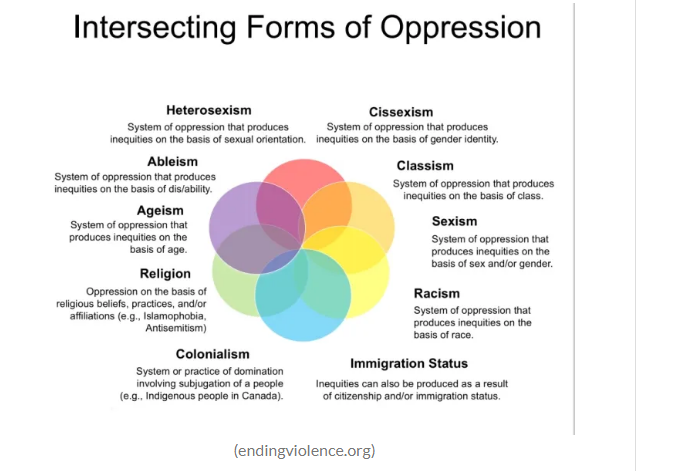

We introduced the concept of intersectionality in Chapter 1, as a way of identifying your own social location. Another way of understanding intersectionality though, is by looking at categories of oppression. This intersection is detailed in figure 9.10.

Figure 9.10 Intersecting forms of oppression: This infographic is another way to think of intersectionality and how different forms of oppression can amplify each other. Figure 9.10 mage Description

Each of these layers of oppression connects with the other sources of oppression. Social locations such as race, ethnicity, class and socioeconomic status, sexuality, sex, and gender, all impact mental health outcomes. Kimberle Crenshaw, who popularized the concept of intersectionality, spoke recently about the urgency of intersectionality in The Urgency of Intersectionalitty [YouTube Video].

While you’re watching the video, think about how intersectionality may impact mental health. How does a White woman experience a mental health crisis differently than a Black woman, for example? One research paper examines the intersectionality of mental health, racism, sexism, and ageism. If you’d like to learn more, please read: Triple Jeopardy: Complexities of Racism, Sexism, and Ageism on the Experiences of Mental Health Stigma Among Young Canadian Black Women of Caribbean Descent

Although there are many ways to layer social location, we look more deeply at Race and Ethnicity, Class, Language, and Gender.

9.3.1 Race and Ethnicity

Figure 9.11 #TerpsTalk: Intersection of Race and Mental Health [YouTube Video]. Please watch the first 10 minutes of this video discussing both the needs for mental health services and the barriers to services for BIPOC people. What issues are new as part of our discussion of social problems?

The video in figure 9.11, “The Intersection of Race and Mental Health,” presents some of the newest research on race and mental health. It specifically calls out racial trauma as a cause of mental health issues. Racial trauma is one term used to describe the physical and psychological symptoms that people of color often experience after being exposed to stressful experiences of racism (Carter 2007). We’ve talked already about microaggressions in Chapter 1. We’ve discussed the police violence and disproportionate incarceration of people of color in Chapter 6. These experiences, and many others, contribute to racial trauma.

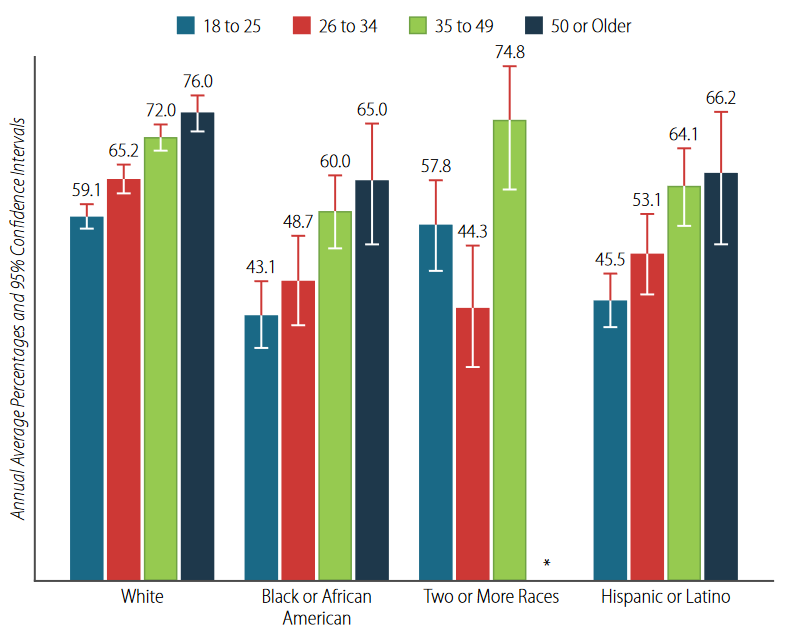

Making this problem worse, Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have less access to mental health services. In the chart in figure 9.12 Mental Health Service Use in the Past Year among Adults with Serious Mental Illness, by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group, we notice that White people use mental health services more than any other group.

Figure 9.12 Mental Health Service Use in the Past Year among Adults with Serious Mental Illness, by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group: 2015–2019, Annual Averages

We can also examine the amount of unmet needs for mental health services according to race and ethnicity. When we do this, we see:

Levels of unmet need (not receiving specialist or generalist care in past 12 months, with identified diagnosis in same period)

- African Americans – 72 percent

- Asian Americans – 78 percent

- Hispanics – 70 percent

- Non-Hispanic Whites – 61 percent

Black and Brown people have a harder time accessing quality mental health services, and when they do receive services, they are more likely to have a negative experience. Some cultures have more stigma around mental health issues that White Americans generally have, and that can be a barrier for some immigrants and some first and second generation Americans to seek services.

For immigrants, mental health providers often lack language and cultural competency skills, which makes the treatment much less effective. Finally, racial and ethnic minorities are profoundly underrepresented in research and clinical trials for new treatments. This means that their bodies and life experiences are not considered when new treatments and medications are developed.

9.3.2 Class Issues in Mental Health Treatment

One of the most consistent findings across studies is that lower socioeconomic groups have greater amounts of mental illness. Why is this the case?

One of the earliest studies of the sociology of mental health came from the University of Chicago in the 1930s. You may remember this school from our discussion of Jane Addams in Chapter 1. Sociologists explored whether mental illness caused poverty or whether poverty caused mental illness. The two researchers who led this project—Faris & Dunham—looked at psychiatric admissions to Chicago hospitals by neighborhood. What they found was rather shocking—there was a nine times increased rate of schizophrenia from people who came from poorer neighborhoods, than from more middle-class neighborhoods. Faris and Dunham tried to figure out why.

One idea was social selection, the idea that lower class position is a consequence of mental illness. Mentally ill people would drift downward into lower income groups or poorer neighborhoods, because they couldn’t keep jobs.In addition to considering social selection, they considered social causation, also. In this model, lower class position was a cause of lower class position is a cause of mental illness.

Results of this early study came back mixed. At first, Faris & Dunham said that the isolation and poverty of living in the central city created schizophrenia—cause. But then, they changed their mind, and said people with schizophrenia have downward drift, and moved to the central, poorer part of town, after developing schizophrenia—effect. Later studies have found that Faris & Dunham’s study was actually trying to tell us that it’s both—cause and effect. Social selection theories and social causation theories can be used to account for schizophrenia.

As our infographic on equity and mental health shows, people with mental health issues can struggle with educational and economic stability, because sufficient social supports are not in place to support them. And, poverty itself can be a risk factor for poor mental health. This article from the Guardian, Mental Illness and Poverty: You Can’t Tackle One Without The Other might help you to make more sense of this complex relationship.

9.3.3 Gender

Figure 9.13 Teen Intersectionality Series: Mental Health & Gender [YouTube Video]. As you watch this 4 minute video consider how gender identity and sexual orientation might impact mental health and mental well-being.

Gender has often been an explanation of the occurrence of mental health and mental illness. While traditional explanations focus on women, as explored in the previous section, newer research is focusing on the interactions of nonbinary and gender fluid folx and their mental health. The video in 9.13 provides some detail around this experience.

But why is gender such a persistent variable in all of our social problems? To make sense of this, let’s explore the social structure of patriarchy more carefully the next section.

9.3.4 Licenses and Attributions for Social Location and Mental Health

“Social Location and Mental Health” by Kate Burrows and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.9 Equity Matters to Mental Health https://ontario.cmha.ca/equity/

Figure 9.10 Intersecting forms of oppression (ending violence.org as quoted in https://www.yoair.com/blog/anthropology-overview-of-the-concept-of-intersectionality/)

Figure 9.11 Intersection of Race and Mental Health Video.https://youtu.be/eiOv_xXsUI0

Figure 9.12 Mental Health Service Use in the Past Year among Adults with Serious Mental Illness, by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group: 2015–2019, Annual Averages

Figure 9.13 Teen Intersectionality Series: Mental Health & Gender https://youtu.be/caSr5rHnxtY