1.4 Social Problems in a Diverse World

Although sociologists have sometimes explained social problems by using only one dimension of diversity—just age, or just race, or just gender—such models do not capture the interdependent nature of society and related social problems. More powerfully, sociologists use the concepts of social identity, social location, and intersectionality to begin to explain systemic inequalities.

As a member of society, you have both a social identity and a social location. A social identity conveys who you are to others. A social location describes your relationship to power and privilege in your society. Both social identity and social location use multiple dimensions of diversity. In this section, we explore these concepts and apply them to our classroom and community experience, laying the groundwork for the challenging discussions to come.

1.4.1 Social Identity

Figure 1.16 American sociologist Allan Johnson explores social identity and social location in his work.

A social identity consists of the combination of social characteristics, roles, and group memberships with which a person identifies. According to Johnson, shown in figure 1.16, social identity is “the sum total of who we think we are in relation to other people and social systems” (2014:178). Our social identity includes the following attributes:

- Social characteristics: These can be biologically determined and/or socially constructed and include sex, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, age, sexuality, nationality, first language, and religion, among other characteristics.

- Roles: These indicate the behaviors and patterns utilized by an individual, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time.

- Group memberships: These are often related to social characteristics (e.g., a place of worship) and roles (e.g., a moms’ group), but could be more specialized as well, such as being a twin, a singer in a choir, or part of an emotional support group.

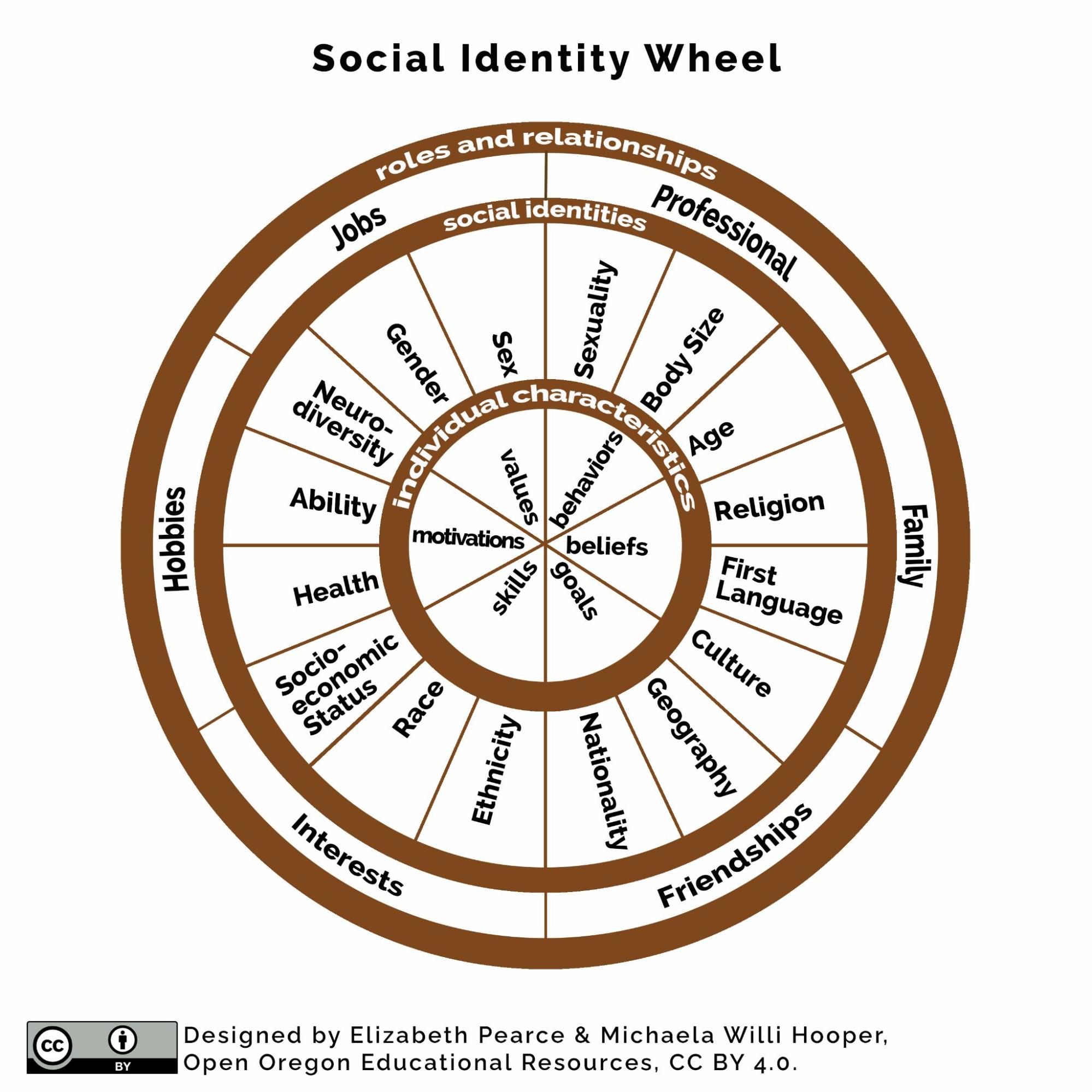

Figure 1.17 Social identity wheel, Figure 1.17 Image Description

The social identity wheel in figure 1.17 includes some common categories for social characteristics. The characteristics in the center of the wheel describe our individual characteristics. Our social identities include social categories that might describe us. The outside of the wheel includes our social roles and relationships. Each of us determines our social identity. That means we determine which of our social characteristics, roles, and group memberships are most important to our own identities. While each of us gets to determine our own social identity, it is important to note that others may identify us differently than we identify ourselves. Our most notable physical aspects may signal something different than our personal lived experience.

The following sections will look more deeply at how sociologists define these social characteristics.

1.4.2 Dimensions of Diversity

Groups of people can be diverse across many dimensions of diversity. This section defines the dimensions the sociologists commonly use to make sense out of social problems: race, ethnicity, gender, age, class, sexual orientation, and ability/disability. In other chapters, we will explore other dimensions including level of education, geography, national origin or citizenship status, neurodiversity, and many other categories. As we look at specific social problems, we will use several of these dimensions to examine structural inequalities and individual experiences.

Figure 1.18 Race is socially constructed but real in its consequences. In this picture of protest, Black people assert that Nothing Matters Until Black Lives Do.

1.4.2.1 Race

One dimension of diversity we focus on is race. While differences in physical characteristics are often used to define race, in general, there is no consensus on this term. Historically, race has been defined using observable physical or biological criteria, such as skin color, hair color or texture, facial features, etc. However, social and physical scientists now understand that the definition of race based on these biological characteristics are both inaccurate and harmful. Research has proven no biological foundations for race. Human racial groups are more alike than different. In fact, most genetic variation exists within racial groups rather than between groups. Based on this, racial differences in areas such as academics or intelligence are not based on biological differences but are instead related to economic, historical, and social factors. (Betancourt and Lopez 1993).

Instead, race has been socially constructed and has different social and psychological meanings in many societies. In the United States, people of color experience more racial prejudice and discrimination than White people. The meanings and definitions of race have also changed over time and are often driven by policies and laws. We discuss race in every chapter, but we explore the social construction of race more deeply in Chapter 6.

1.4.2.2 Ethnicity

Figure 1.19 Ethnicity: Latinx Family Photo The ethnicity of hispanic or Latino was only recently recognized by the US Census.

Ethnicity refers to one’s social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group (Pinderhughes 1989). Ethnicity is not the same as nationality, which is a person’s status of belonging to a specific nation by birth or citizenship. For example, an individual can be of Japanese ethnicity but British nationality because they were born in the United Kingdom. Ethnicity is defined by aspects of subjective culture such as customs, language, and social ties (Resnicow Braithwaite et al. 1999).

While ethnic groups are combined into broad categories for research or demographic purposes in the United States, there are many ethnicities among the ones you may be familiar with. Latina/o/x or Hispanic may refer to persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish, Dominican, or many other ancestries. Asian Americans have roots in over 20 countries in Asia and India. The six largest Asian ethnic subgroups in the United States are Chinese, Asian Indians, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese. This report from the Pew Research Center reveals more details about the complexity of ethnicity for Asian Americans.

1.4.2.3 Gender

Figure 1.20 Gender is socially constructed and real in consequences. Depending on your gender identity you might have access to a public bathroom, or not.

Gender refers to the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in our society. Gender is different from sex, which is a biological description involving chromosomes and internal/external reproductive organs. As a socially constructed concept, gender has magnified the perceived differences between females, males, and nonbinary people. The overreliance on gender categories has created limitations in attitudes, roles, and how social institutions are organized. We can see these limitations when we look at what jobs we think are appropriate for women, men or nonbinary people. We notice it when we look at how parenting responsibilities and household chores are divided within families.

Gender is not just a demographic category. Gender also influences gender norms, the distribution of power and resources, access to opportunities, and other important processes (Bond 1999). For those who live outside of these traditional expectations for gender, the experience can be challenging. In general, the traditional binary categories for sex, gender, and gender identity have received the most attention from both society and the research community, with only more attention to other gender identities (e.g., gender-neutral, transgender, nonbinary, and GenderQueer) in recent years (Kowciw, Palmer and Kull 2015). We explore this concept more in the Diversity Box for Queer in Chapter 3 and gender and patriarchy in Chapter 9.

1.4.2.4 Age

Figure 1.21 Old women smiling. Although old age is often stigmatized, it’s not all about death.

Age describes the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult. Power dynamics, relationships, physical and psychological health concerns, community participation, and life satisfaction can all vary for these different age groups. The field is starting to include aging issues in research, but research on older adults is still limited in social science journals (Cheng and Heller 2009). Although the skills, values, and training of community psychologists and sociologists would likely make a difference in the lives of older adults, the attitudes within our profession and society are current barriers. We explore aging more deeply in Chapter 10.

1.4.2.5 Class

Figure 1.22 Houseless person on the streets of New York beneath a sign for TUMI, a store that sells exclusive bags for travel.

Like the other components of diversity, social class is socially constructed and can affect our choices and opportunities. This dimension can include a person’s income or material wealth, educational status, and/or occupational status. It can include assumptions about where a person belongs in society and indicate differences in power, privilege, economic opportunities and resources, and social capital.

Social class and culture can also shape a person’s worldview or understanding of the world. It can also influence how they feel, act, and fit in. It can impact the types of schools a child may attend, a senior’s access to health care, or an adult’s experience of work. The differences in norms, values, and practices between lower and upper social classes also impact well-being and health outcomes (Cohen 2009; Pearce 2020). Social class and its intersection with other components of one’s identity are important for social scientists to understand. We will explore social class, which is sometimes also called socioeconomic class, in Chapter 4.

1.4.2.6 Sexual Orientation

Figure 1.23 Sexual Orientation Sociologists now understand that sexual orientation exists on a continuum. Many identities are possible.

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another in relation to their own sex or gender. The definition focuses on feelings rather than behaviors since individuals who identify with a minority sexual orientation experience significant stigma and oppression in our society (Flanders et al. 2016). Sexual orientation exists on a continuum or multiple continuums and crosses all dimensions of diversity (e.g., race, ethnicity, social class, ability, religion, etc.).

Sexual orientation is different from gender identity or gender expression. Over time, research on gay, lesbian, asexual, and bisexual identities has extended to other sexual orientations such as pansexual, polysexual, and fluid, and increasingly more research is being conducted on these populations within the social sciences (Kosciw, Palmer, and Kull 2015). We explore the social construction of sexual orientation more deeply in Chapter 3.

1.4.2.7 Ability/Disability

Figure 1.24 Disabled and Here. Physical ability and disability look different for every person. Figure 1.24 Image Description

Please take a moment to really look at the picture in figure 1.24. All of these people are labeled as disabled. What do we mean when we use this label? Disabilities refer to conditions that pose barriers or challenges. These conditions may be visible or hidden, temporary or permanent. They can impact individuals of every age and social group. Traditional views of disability follow a medical model, primarily explaining diagnosis and treatment models from a pathological perspective (Goodley and Lawthorn 2010). In this traditional approach, individuals diagnosed with a disability are often discussed as objects of study instead of complex individuals impacted by their environment.

A social model of ability, which is the perspective of these authors, views diagnoses from a social and environmental perspective and considers multiple ecological levels. The experiences of individuals are strongly valued in the social model.

Defining disability or ability also depends on culture (Goodley and Lawthorn 2010), and may impact whether or not certain behaviors are considered sufficient for inclusion in a diagnosis. For example, cultural differences in the assessment of “typical” development have impacted the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in different countries. Further, diagnoses or symptoms can be culturally specific, and culture may influence how symptoms are communicated (Office of the Surgeon General et al. 2001). The experience of culture can significantly impact lived experience for individuals diagnosed with a disability. We look at the social construction of ability and disability in Chapter 3.

1.4.3 Social Location and the Wheel of Power and Privilege

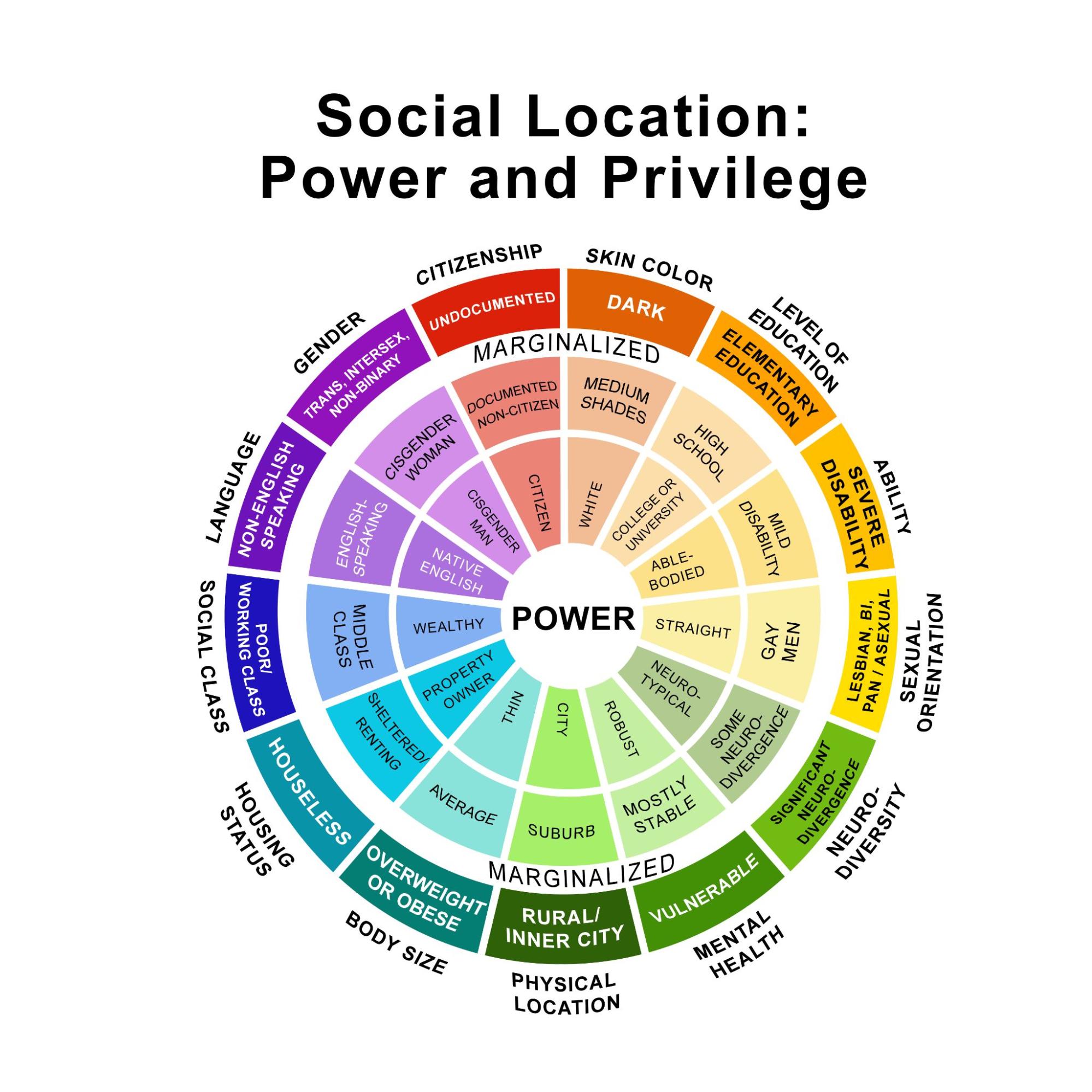

Figure 1.25 Wheel of Power and Privilege. Figure 1.25 Image Description

Describing just one characteristic of a person’s identity is insufficient to understand them. Similarly, understanding any social group requires understanding their complex experiences. For this, we turn to the concepts of social location and intersectionality.

Social location is defined as the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location, in relationship to power and privilege. In the circle in figure 1.25, the word power sits at the center of the circle. People with characteristics near the center of the circle, such as White, able-bodied property owners have more power and privilege. Power is the ability to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance (Piven 2007). Privilege is “an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson 2018:148). People in the center are also known as people in the dominant group.

Non-dominant, or marginalized groups, are located at the outside of the wheel. One definition of marginalization is “a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are relegated to the fringes of a society, being denied economic, political, and/or symbolic power and pushed towards being ‘outsiders’” (Oxford Reference n.d.). People in marginalized groups have less access to power. These identities may include having a grade school education, being houseless, or being queer.

Rather than only being indicators of your identity, these components begin to describe the access that people in a group have to wealth, status, political power, economic stability, or other social resources. Identities that align with the groups who have power convey privilege. Those identities that align with less powerful groups are less likely to convey privilege.

Citizens, for example, have the right to vote, the right to travel in and out of countries safely, and the possibility of applying for federal financial aid to finance school. Citizenship itself conveys power to that social group. At the far end of citizenship, we find people who are undocumented or living in a country without having any rights of citizenship. Undocumented people cannot vote, legally leave the country, or receive any government aid to pay for education. Undocumented people may be deported at any time. Being safe where you live is a privilege. When you lack this safety, you experience marginalization.

Figure 1.26 Bandages for people with dark skin available in 2021

White privilege is one dimension of privilege. In “White Privilege, Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” sociologist Peggy McIntosh lists the privileges, or unearned advantages, that White people have (McIntosh 1989). Her 26 examples include some less obvious privileges that come from having white skin. Here are some of them:

- I can if I wish arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

- If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I want to live.

- I can choose blemish covers or bandages in “flesh” color and have them more or less match my skin. (the bandages in figure 1.26 were introduced in 2021)

McIntosh makes White privilege visible. By listing circumstances in which this group receives benefits that they may not even notice, she begins to describe inequalities based on group membership.

More recently, sociologist Allan Johnson expands this discussion of privilege by applying it to gender, sexual orientation, and ability/disability categories in addition to race and ethnicity. He writes,

Many of these examples of privilege—such as preferential treatment in the workplace—apply to multiple dominant groups, such as men, whites, and the non-disabled. This reflects the intersectional nature of privilege, by which each form has its own history and dynamics, and yet they are also connected to one another and have much in common.

Also, consider how each example might vary depending on other characteristics a person has. How, for example, would preferential treatment for men in the workplace be affected by race or sexual orientation? Finally, remember that these examples describe how privilege loads the odds in favor of whole categories of people which may not be true in every situation and for every individual, including you….

- Whites who are unarmed and have committed no crime are far less likely than comparable people of color to be shot by police, to be challenged without cause and asked to explain what they are doing, or subjected to search. Whites are also less likely to be tried, convicted, or sent to prison regardless of the crime or circumstances. As a result, for example, although Whites constitute eighty-five percent of those who use illegal drugs, less than half of those in prison on drug use charges are white.

- Heterosexuals and Whites can go out in public without having to worry about being attacked by hate groups. Men can assume they won’t be sexually harassed or assaulted just because they are male, and if they are victimized, they won’t be asked to explain their manner of dress or what they were doing there. (Johnson 2018:26-27)

Johnson’s list of privileges continues for multiple pages, highlighting the ways in which structures of society result in unearned benefits for some people and oppression for others.

You may respond differently to this model of power and privilege than someone else in your class. You may sigh with relief because you see the struggles you face every day in this model. You may be confused or uncertain. You may feel the model is complicated and hard to understand. You may be angry because you don’t see yourself as a victim or powerless. You may feel ashamed or “bad” for having privilege.

Any of these emotional reactions (and others I may not have mentioned) are normal. Exploring these reactions is useful for two reasons. First, when you notice your reaction, you gain self-knowledge. The Wheel of Power and Privilege is powerful, but it can be just colorful ink on the page if you don’t consider what it means. Understanding our own personal reaction to it helps us develop empathy for ourselves and for those we see as “other.” Second, these emotional reactions give us the opportunity to pause, to take a breath before we react. This space between feeling and response allows us to choose a response that is both authentic and respectful. Our response, even when it contains sadness, anger, or guilt, can connect us with others, if we ask questions and listen respectfully to the answers.

1.4.3.1 The Wheel of Power and Privilege Describes Structural Oppression and Structural Privilege

In addition to any emotional reaction, though, the wheel of power and privilege model is useful in moving the conversation from the experience of one individual to structural experiences of oppression. This model explains systemic inequalities, not personal ones. Systems of law, education, business, medicine, and government are constructed with rules, policies, and practices that create a social world that is more powerful and more enduring than any one individual or group of individuals.

When you consider how changes in law change society, consider these examples. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. In 1967, in the case of Loving v. the State of Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that laws that prevented racial intermarriage were unjust. Until 1993, some states still had laws that rape could not occur within marriage, because consent was already part of the marriage contract. In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples.

These laws visibly reverse decades and sometimes centuries of racism, sexism, and homophobia embedded in our social policies, practices, and interactions. They specifically name the structure of inequality and work to dismantle it. In every case, we have yet to realize the full freedoms and protections under these laws. The laws are one example of a social structure that conveys power unequally between groups.

1.4.3.2 The Wheel of Power and Privilege Does Not Equate Lack of Power with Lack of Value or Agency

Any individual locating themselves on this wheel may take strength or pride in any of their identities. In fact, it is a sign of resilient mental health to accept and integrate all components of your identity. Movements such as Black Power or Gay Pride celebrate this acceptance. People who experience mental health issues can savor the resilience they gain as they deal with their challenges. Neurodiverse people can champion a different way of thinking. As people age, they can savor the wisdom and wise seeing that can come from getting older. Marginalized, then, doesn’t mean without value. It means that a marginalized person lives within a system that harms or does not fully nurture them.

Further, a group that experiences oppression may take back their power. The very characteristic that puts them outside of the norm may be the identity that supports them in taking action. An oppressed group can clearly see the changes needed to invest in health care that works for everyone, or housing options so no one sleeps in the street, or family support that allows all members to thrive. The social location itself becomes a ground for change.

1.4.3.3 The Wheel of Power and Privilege Demonstrates Intersectionality

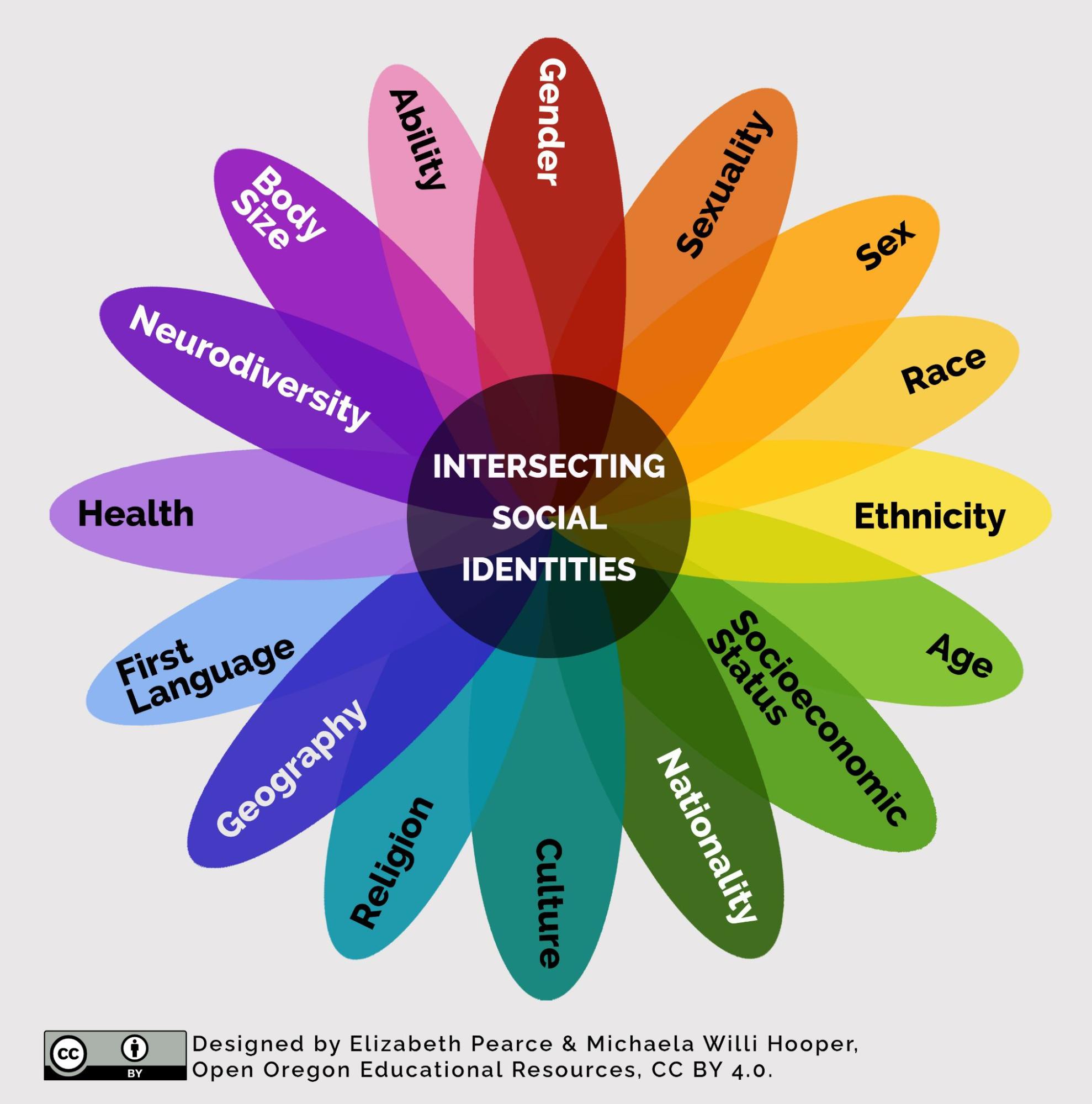

Figure 1.27 Image of Intersectionality, Figure 1.27 Image Description

As the social identity wheel (figure 1.17) and the wheel of power and privilege (figure 1.25) illustrate, social identity and social location are composed of multiple factors. Today, these multidimensional models are widely used to describe parts of society. Before the twenty-first century, many sociological models focused on one dimension of identity or location to discuss social issues. Single determinant models focused only on race, gender, class, or age as the most important explanation for a person’s experience. However, these models are insufficient.

Intersectionality is the idea that inequalities produced by multiple and interconnected social characteristics can influence the life course of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations. This concept is illustrated in figure 1.27. We see that social locations overlap.

Intersectionality studies have their origin with the Combahee River Collective. The collective was founded in 1974 by a group of Black feminist women in the United States who challenged how White feminist and civil rights movements did not address the needs of Black women. In the Combahee River Collective Statement, they write:

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face. (Combahee River Collective 1978:n.p.)

These Black women see that the oppression of race, class, gender and sexual identity are interconnected. They argue that we must understand these interlocking systems, and work to dismantle them.

Figure 1.28 Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, black lawyer, scholar and activist articulated the theory of intersectionality.

Articulated most recently by Black lawyer, scholar and activist Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw (figure 1.28), intersectionality asserts that race, class, gender and other social locations must be considered simultaneously when we want to understand any group’s relationship to power and privilege. Crenshaw exposes the ways that gender and race have been historically divided into separate fields of study. Because of this division, “race” (the universal racial subject) ends up referring to the experiences of men of color. Meanwhile in studies of “gender,” White women are perceived as the universal female subject. However, we know that Black women have different experiences of discrimination and oppression than Black men or White women. She writes,

Intersectionality is…. a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power. Originally articulated on behalf of Black women, the term brought to light the invisibility of many constituents within groups that claim them as members but often fail to represent them.

When sociologists look at how d/Deafness is experienced differently by White women, men, or non binary people and Brown and Black non-binary people, men, and women, they are using intersectional analysis. To listen to Crenshaw in her own words, you could watch this TED Talk, “The Urgency of Intersectionality.”

1.4.4 Applying Social Identity and Social Location to One Life

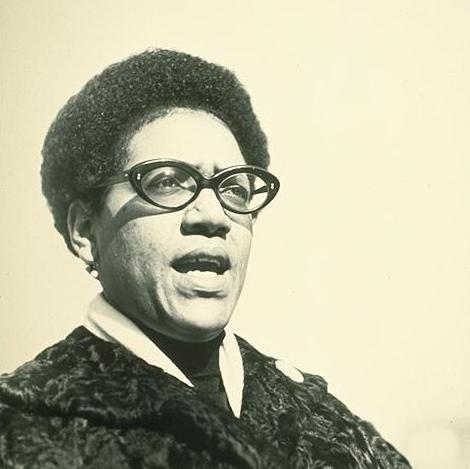

Figure 1.29 Audre Lorde Black Woman

My fullest concentration of energy is available to me only when I integrate all the parts of who I am, openly, allowing power from particular sources of my living to flow back and forth freely through all my different selves, without the restriction of externally imposed definition.

—Audre Lorde, self-described Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, and poet (figure 1.29)

It can be challenging to move from the individual to community to social structure and back again when making sense of the social world. As a practice, I offer my own experience in the following section.

1.4.4.1 My Social Identity

My wheel of social identity comprises many social roles. Most relevant to this book, I am a writer. I am a teacher of sociology, GED, and ESOL. I am an activist and a member of a healing community related to the Echo Mountain Fire. I am White, female, and at the time of this writing, 56 years old. I am a daughter and a sister. I am a wife in a long-term lesbian relationship. I am an ordained interfaith/interspiritual minister. I look forward to being able to sing in a choir again, and I am a beginning kayaker. Some of these identities have stayed consistent. I was born premature and have some hidden physical disabilities, for example. Other identities change over time. I look forward to my aging and the power that comes with being a wisewoman. Although I am wholly myself in all situations, some of the layers of my identity are core to how others see me.

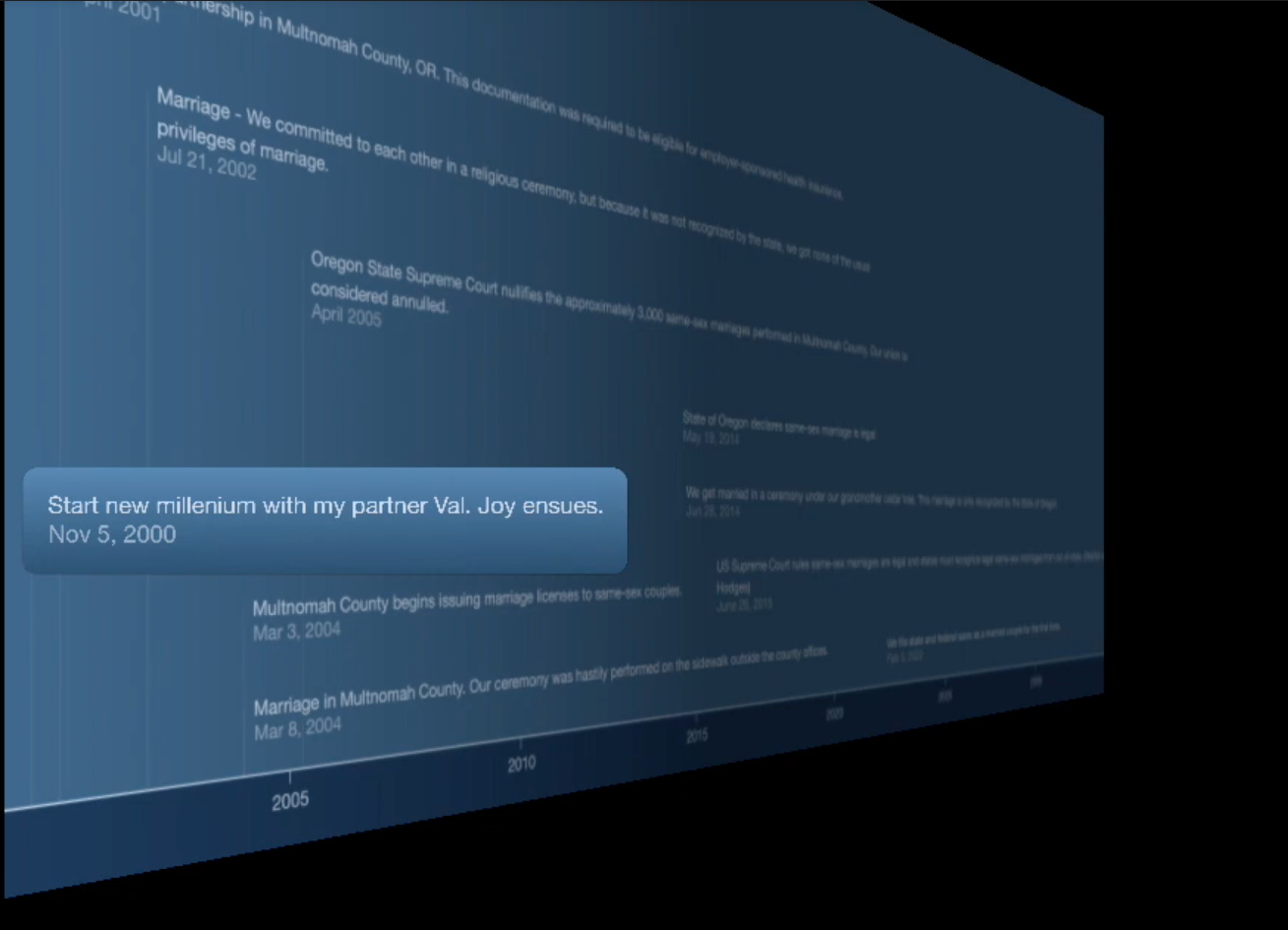

1.4.4.1 My Social Location

My social location includes both experiences of oppression and privilege. I experience systemic inequality because of my queer identity. My love story with my wife is both beautiful and constrained by homophobic political systems. We fell in love in 2000, declaring our relationship to ourselves and our families late in that year. While this declaration was not without challenges, it required no state or government intervention to be real. What followed, however, was a decades-long struggle for legal, religious, and social legitimacy for our relationship. This struggle involved many institutions/governing bodies, as shown in the timeline in figure 1.30.

Figure 1.30 Kim and Val Get Married [ video ]

As of 2022, we can be confident that our families and health care institutions will respect our need to be together if we are sick or require hospitalization. We expect that retirement centers will allow us to live in the same room together if we can’t take care of ourselves. Our money and our resources belong equally to both of us. Although we are not safe to be visible everywhere, worldwide, we love each other freely. We are grateful that we can live in relationship so openly, and yet, we also acknowledge that part of our struggle is the struggle against heterosexism, heteronormativity, and homophobia, components of social structure that confer rights and power to people who live and love in female/male relationships.

1.4.4.2 My Power, Privilege, and Intersectionality

While I am marginalized in my social location of queer, I also experience privilege as a White, educated woman. This privilege supports me in softening the impact of queerness. Because I can live where I choose, I can choose a community and physical location that is beautiful, restorative, and safe. Because I am well educated I can find work that I enjoy and that pays well. My education and professional work experience resulted in digital fluency, so I can find communities locally and online that nourish the various layers of my identity. Although I’ve led a disciplined life, many of these privileges are unearned.

This combination of power and marginalization, when applied to social groups, is what Crenshaw points out in her work on intersectionality. Race, gender, sexual orientation, or class alone can not completely define how someone experiences the social world. Instead, combinations of race, class, gender, age, and origin interact in a complex matrix of power and privilege to create your experience.

1.4.4.3 My Identity and Agency

Figure 1.31 Val and Kim at Women’s March in Newport Oregon, Jan 21, 2017 (with coffee because we live in Oregon)

When you look at our relationship timeline, it is obvious that Val and I experience systemic inequality. Straight people who choose to marry don’t usually need multiple ceremonies in order to have the government or their house of worship validate their relationship. However, my queer identity is also a source of my personal power and my individual willingness to take action. Like many feminists of the 1970s, Val lived “the personal is the political” when she knocked on her neighbors’ doors. By telling them that she was a lesbian, or coming out, she challenged their assumptions that to be lesbian was to be strange, deviant, or dangerous. We found great joy in singing with lesbian choirs over many decades. My experience as a lesbian is steady fuel for my commitment to personal authenticity, empathy, and social justice (figure 1.31).

1.4.5 Applying What You Know: Microaggressions and the Diverse Classroom and Community

Figure 1.32 Dr. Maya Angelou, Poet, Dr. Maya Angelou reciting her poem “On the Pulse of Morning” at U.S. president Bill Clinton’s inauguration, January 20, 1993.

Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.

—Dr. Maya Angelou, American author, poet, and civil rights activist (figure 1.32)

Figure 1.33 Eliminating Microaggressions: The Next Level of Inclusion [TEDx Video]

These discussions of structural inequality, a condition where one category of people is attributed an unequal status in relation to another category of people (United Nations n.d.), begin to help us understand why we have social problems in the first place. They also help us understand why social problems are hard to solve. But how can we use these models to start making a difference in our communities today?

We can take action at the level of microaggressions. According to Tiffany Alvoid, JD, an attorney who graduated from the UCLA School of Law, microaggression is “a term used for brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative prejudicial slights and insults toward any group” (Alvoid 2019). In the video in figure 1.32, Alvoid provides examples of several microaggressions. One common microaggression is asking, “Where are you from?”, particularly when a White person is talking to a person of color who speaks with an accent.

In another example, a Latinx student shared that they were serving a customer in a local restaurant. The customer, who was White, said, “You are one of the good ones” to compliment the quality of their work. This compliment implied that everyone who looked like them wasn’t “good.” Another microaggression is to say, “I’m so OCD,” when in fact, you are just stressed out. This minimizes the struggles of those who actually have obsessive-compulsive disorder.

All of us can commit microaggressions, particularly when we are acting in our privilege. All of us can experience microaggressions, but people with less privilege experience them more. Microaggressions are a form of discrimination and marginalization.

1.4.6 Living Diversity Well

We have now explored models of inequality as concepts and seen how they work when applied to daily life. What are the norms of behavior that we choose to use when we interact in our classroom and in our wider community? When you focus on differences alone, it can lead to polarization. By bringing interdependence and relationship into our conversations with each other, we can bridge our differences and use our collective diversity as a communal strength. The following is a list of suggestions to support you in managing your own reactions and any conflict which may arise as we tackle these challenging concepts together:

- Breathe. When you notice your breathing, you notice your own physical and emotional reaction to the information you are learning or the environment around you.

- Take care of yourself. This book and this class address issues and experiences that may challenge your worldview, your beliefs, and your ideas about yourself and others. Because we discuss difficult life experiences like houselessness, sexual violence, addiction, and death and dying, you may experience strong feelings. If this occurs, please take care of yourself. Your instructor or your college may have support resources available to you.

It may also help to consider this concept of radical self-care, championed by the activist leader and scholar Angela Davis. She encourages all of us to look at self-care as a method for creating healthier ways of being, one caring step at a time. Angela Davis herself describes the concept in “Radical Self Care [YouTube Video].” She says that eating right and taking care of your mental and spiritual health are essential when doing activist work. Activist and therapist Resmaa Menakem also reminds us that we also have access to resources that may support our healing. This blog post “Understanding and Cultivating Your Resources” may help you figure out what to do to get support. - Pause before reacting. In the microaggressions video referenced earlier in this section, Alvoid suggests the use of the pause. She says, “Before you ask someone a personal question in the [classroom], pause” (Alvoid 2019). The pause allows you to consider why you are speaking. It also allows you to consider the impact of what you might say. Will the words you are considering cause harm to someone else? Sometimes it is important to disagree with someone. Even then, you can disagree with respect.

- Speak authentically. When you tell the truth about who you are, you bring richness into our collective room. Please consider the dynamics of who is speaking, also. If you speak often, you may want to be quieter to allow the voices of others. If you are quiet, consider being brave and speaking more. The wholeness of the world requires your voice.

- Cultivate cultural humility. Cultural humility is the ability to remain open to learning about other cultures while acknowledging one’s own lack of competence and recognizing power dynamics that impact the relationship. Within cultural humility, it is important to engage in continuous self-reflection, recognize the impact of power dynamics on individuals and communities, embrace not knowing, and commit to lifelong learning. This approach to diversity encourages a curious spirit and the ability to openly engage with others in the process of learning about a different culture. As a result, it is important to address power imbalances and develop meaningful relationships with community members in order to create positive change. A guide to cultural humility is offered by Culturally Connected, a group that works in health and health literacy in British Columbia, Canada.

- Demonstrate compassion. We all share a common experience of living and loving in this world. Our differences are often used as a way to divide us. However, we are also intricately interconnected. Consider how you could use empathy to foster both clarity and connection.

1.4.7 Licenses and Attributions for Social Problems in a Diverse World

1.4.7.1 Open Content, Shared Previously

1.4.1 and 1.4.2 is adapted from “The Social Construction of Difference” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems.

Figure 1.16. “Allan Johnson” by Washington State University is licensed under CC BY-SA 1.0.

Figure 1.18. Photo by nappy is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Figure 1.19. Photo by Rajiv Perera is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.20. Photo by Vise is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 1.21. Photo by Artyom Kabajev is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.22. Photo by Nate Johnston is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.23. Photo by nappy is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Figure 1.24. “Disabled And Here” by Chona Kasinger is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.28. “Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw” by Mohamed Badarne is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.29. “Audre Lorde” by Elsa Dorfman is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 1.32. “Dr. Maya Angelou” by Clinton Library, Wikimedia Commons, is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.33. “Eliminating Microaggressions” by Tiffany Alvoid, TEDxOakland is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

1.4.7.2 All Rights Reserved Content

Applying Social Identity” and related figures, which are all rights reserved. Please request permission to re-use the author’s personal story.

Figure 1.26. Photo from “The Story Behind BAND-AID® Brand OURTONE™ Adhesive Bandages” © Johnson & Johnson is included under fair use.

Figure 1.30. “Kim and Val Get Married” © Kimberly Puttman and David Boyes is all rights reserved.

Figure 1.31. Photo by Kimberly Puttman is all rights reserved.

1.4.7.3 Open Content, Original

“Social Problems in a Diverse World” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 with the exception of section 1.4.4, “Applying Social Identity” and related figures, which are all rights reserved. Please request permission to re-use the author’s personal story.

Section on Intersectionality remixed from “Introduction to Sociology” by Matthew Gougherty and Jennifer Puentes and “Social Change in Societies” by Aimee Krouskop. Manuscripts in press.

Figure 1.17. “Social Identity Wheel” by Elizabeth Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.25. “Social Location: Power & Privilege” by Lauren Antrosiglio and Kimberly Puttman is CC BY 4.0. Adapted with permission from Sylvia Duckworth.

Figure 1.27. “Intersecting Social Identities” by Elizabeth Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 1.31. Photo by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Image Description for Figure 1.17:

The social identity wheel has common characteristics in the middle that remain stable including, national origin, race/ethnicity, mental/physical ability, sexual orientation, age, gender, gender identity or expression. The characteristics on the outside can change over time like, work experience, education, appearance, religion, income, language and communication skills, organizational role, family, and political belief.

[Return to Figure 1.17]

Image Description for Figure 1.24:

Six disabled people of color smile and pose in front of a concrete wall. Five people stand in the back, with the Black woman in the center holding up a chalkboard sign reading “disabled and here.” A South Asian person in a wheelchair sits in front.

[Return to Figure 1.24]

Image Description for Figure 1.25:

A multicolored wheel with a center that says power. There are 13 factors in the wheel. Each factor lists characteristics of people closer to the center of power and further from the center of power. The people furthest from the center of power are more marginalized. For the factor of skin color, dark is the most marginalized, medium shades in the middle, and white closest to the center of power. For the factor of level of education, elementary education is the most marginalized, high school is in the middle, and college or university is closest to the center of power. For the factor of ability, severe disability is the most marginalized, mild disability is in the middle, and able-bodied is closest to the center of power. For the factor of sexual orientation, lesbian, bi, pan/asexual are the most marginalized, gay men are in the middle, and straight is closest to the center of power. For the factor of neurodiversity, significant neurodivergence is the most marginalized, some neurodivergence is in the middle, and neurotypical is closest to the center of power. For the factor of mental health, vulnerable is the most marginalized, mostly stable is in the middle, and robust is closest to the center of power. For the factor of physical location, rural/inner city is the most marginalized, suburb is in the middle, and city is closest to the center of power. For the factor of body size, overweight or obese is the most marginalized, average is in the middle, and slim is closest to the center of power. For the factor of housing status, houseless is the most marginalized, sheltered/renting is in the middle, and property owner is closest to the center of power. For the factor of social class, poor/working poor is the most marginalized, middle class is in the middle, and wealthy is closest to the center of power. For the factor of language, non-English speaking is the most marginalized, English speaking is in the middle, and native English is closest to the center of power. For the factor of gender, trans/intersex/nonbinary is the most marginalized, cisgender woman is in the middle, and cisgender man is closest to the center of power. For the factor of citizenship, undocumented is the most marginalized, documented non-citizen is in the middle, and citizen is closest to the center of power.

[Return to Figure 1.25]

Image Description for Figure 1.27: Image Description for 1.27:A flower-like visualization with a semi-opaque circle in the middle. Rainbow-colored ovals radiate from the middle like petals. These overlap with the oval on either side and with the circle in the middle. Each oval has one of the following social identities written in it:

Nationality

First Language

Religion

Ability

Neurodiversity

Health

Body size

Age

Sex

Gender

Sexuality

Race

Culture

Ethnicity

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Geography